Eugenia Belin Sarmiento

Eugenia Belín Sarmiento (December 29, 1860, San Juan, Argentina - August 2, 1952, Buenos Aires, Argentina) was an Argentinean painter and author. Her works were featured in various international shows, among them the first Exposición Anual de Pintura, Dibujo y Escultura (Annual Exhibition of Painting, Drawing, and Sculpture) for artists of South America in 1893.[1] Critical response to her works has often focused attention on her portraits of her grandfather, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who was president of Argentina from 1868-1874. Eugenia completed many other works as well, including miniatures as well as full size portraits, paintings of flowers, birds, and still lives, and sculptures.

Eugenia Belín Sarmiento | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 29, 1860 |

| Died | August 2, 1952 (aged 91) |

Early years

Eugenia Belin Sarmiento was born in 1860, one of six children of Jules Belín and Ana Faustina Sarmiento.[2] Jules Belín (1829-1863) was a French printer and publisher of the Santiago, Chile newspaper El Ferrocarril. Belin met Domingo Faustino Sarmiento in France in 1848 and moved to Chile, where he published works written by Sarmiento, who was an Argentinian exile in Chile.[3][4] Domingo Faustino Sarmiento went on to be an Argentine politician, writer, and educator, and the president of Argentina from 1868 to 1874.[5] Eugenia's mother, Ana Faustina Sarmiento, was born on July 18, 1832 as a result of a romance between Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (then age 20) and one of his students, María Jesús del Canto (age 17). Sarmiento arranged for Ana Faustina to be cared for by her grandmother, Paula Albarracín de Sarmiento, and recognized her publicly after her marriage to Belin in 1850.[6]

Belin died when Eugenia was only three, and Eugenia was educated at home by her mother and other relatives. Eugenia spent time as a student and disciple of her great-aunt, Procesa del Carmen Sarmiento, who was a renowned painter.[7][8] She was also taught art by her grandmother. She later attended and completed her secondary education at the Escuela Superior de Niñas de San Juan (High School for Girls of San Juan), which her mother directed.

When Eugenia's brother Augusto Belín y Sarmiento was appointed the Argentine consul in Antwerp, Eugenia accompanied him to Belgium, and used the trip to be professionally trained by famous art masters of the time. In 1884, she returned to Buenos Aires permanently.[2][9]

Career

After returning to Buenos Aires, Belín Sarmiento studied art under José Agujari, a renowned painter who was also the first teacher of her contemporary, artist María Obligado.[2]

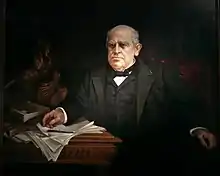

Eugenia focused primarily on portraits, a number of which depicted her grandfather, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, an iconic figure. Among them are a smaller portrait taken in 1888, which she used as a basis for a larger work in 1889. The larger version of the portrait was reported to be in the Museo Historico Nacional, and another version in the provincial legislature of Buenos Aires, as of the 50th anniversary of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento's death in 1938. On September 4, 1938, a full-page color reproduction was published in La Prensa (Buenos Aires). The same issue of La Prensa included a photograph of Eugenia and her sister Elena.[10]

Another family portrait subject was Sarmiento's adopted son Dominguito Fidel Sarmiento, who died in battle against Paraguay.[11] In addition, she painted classical portraits of notable figures of the time such as Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield, Francisco Muniz and José María Estrada.[12] As of 1885, she was contracted by the government of the province of San Juan to paint portraits of Salvador María del Carril, Antonino Aberastain, and Francisco Narciso de Laprida.[13] She also painted portraits of women, with her feminine subjects appearing very similar to the models used by the French painter Charles Joshua Chaplin.[13]

Starting in 1893, Belín Sarmiento sent samples of her works to different exhibitions such as those organized by the Progress Club (Club del Progreso) and at the Second Athenaeum Auditorium. She frequently exhibited works alongside contemporaries such as Julia Wernicke and Maria Obligado, and won her honorable mention awards in 1894, 1895, and 1898, along with a prize in the 1910 Centenary Exposition in Buenos Aires.[2][12][14]

In 1912, she was the first artist from San Juan to participate in the Salón Nacional (National Salon of Visual Arts) of Argentina. Throughout the history of the National Salon, only five women have received a grand prize for painting.[15]

During the 1940s, Julia Ottolenghi cataloged the extant works of Belín Sarmiento, many of which are privately owned and difficult to locate today.[2]

Her works can be found at exhibitions in Argentina at the Franklin Rawson Provincial Museum of Fine Arts and in the Sarmiento historic museum of Buenos Aires, Museo Marc de Rosario, Museo Casa Natal de Sarmiento, and abroad in museums such as the Musée Rodin in Paris.[2]

Responses

Historically, Belin Sarmiento's merit as a painter has often been defined only in terms of masculine influence on her artistry, such as that of her grandfather Domingo. For example, the art critic Eduardo Schiaffino focused almost exclusively on the artistic influence of Domingo on his granddaughter over the fact that Eugenia had been a student of her aunt Procesa Sarmiento, who was a notable painter in her own right.[13]:25–27[16]

More recently, scholars have begun to revisit Belin Sarmiento's works from a modern, feminist viewpoint. In 1988, the works of both Eugenia Belin Sarmiento and Procesa del Carmen Sarmiento were included in the exhibition La mujer en la plástica argentina I (Women in the Argentinean Plastic Arts I) in the Malvinas Cultural Center (Centro Cultural Las Malvinas). The exhibition was part of a pioneering effort to uncover the hidden work of over 250 Argentinean female artists, historic and contemporary, in national, regional and private collections.[13]

Her works were included in a 2013 exhibit focusing on the feminine influence on Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Los universos femeninos: Sarmiento agente de transformaciones (The Feminine Universe: Sarmiento as agent of transformation).[17] In 2019, the Sarmiento historic museum hosted a posthumous exhibition titled Por ella misma - Eugenia Belin Sarmiento (By Her Own Hand - Eugenia Belin Sarmiento).[18]

References

- "Belín Sarmiento, Eugenia". Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Franklin Rawson. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Clarín.com. "La nieta de Sarmiento: mucho más que una pintora de domingo". www.clarin.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Bizzarro, Salvatore (Feb 13, 2017). Historical dictionary of Chile (4th ed.). Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 724. ISBN 9781442276352.

- Garrels, Elizabeth (2005). "Introduction". Recollections of a Provincial Past by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. Translated by Garrels, Elizabeth; Zatz, Asa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. lix–lx. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Sosa de Newton, Lily (1972). Diccionario Biográfico de Mujeres Argentinas. Buenos Aires: Editorial Plus Ultra. pp. 40, 338–339.

- Peiró, Claudia (7 August 2018). "Sarmiento, padre "soltero" de una niña a la que su madre no quería". Infobae. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- "Procesa Sarmiento (1818-1899)". Mujeres pintoras. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Musri, Fátima Graciela; Colecchia, José Antonio (2004). Músicos inmigrantes : la familia Colecchia en la actividad musical de San Juan, 1880-1910 (1 ed.). San Juan, Argentina: EFFHA. ISBN 978-9506053864.

- "Belín Sarmiento, Eugenia". Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Franklin Rawson. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Houck, Helen Phipps (1938). "Literary Periodicals". Hispania. American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese. 21 (4): 315–317. JSTOR 332620.

- "Sarmiento y el arte - Opinión". www.ellitoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- "Arte de la Argentina - El portal de artistas argentinos, museos, salones y principales galerías". www.artedelaargentina.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- Gluzman, Georgina (2015). Mujeres y arte en la Buenos Aires del siglo XIX (PDF). Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Burucúa, José Emilio (1 May 2014). Arte, sociedad y política: Nueva Historia Argentina. Argentina: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial. ISBN 9789500747332.

- Rottenberg, Silvia (21 July 2018). "Culture Ministry hopes to correct gender imbalance with new National Salon rules". Buenos Aires Times.

- Gluzman, Georgina G. (2018). "Mujeres artistas argentinas a fines del siglo XIX: admirables olvidos". Primavera. 7 (2). Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Otamendi, Araceli (2013-02-17). "REVISTAARCHIVOSDELSUR-muestras/arte: Los universos femeninos. Sarmiento agente de transformaciones". REVISTAARCHIVOSDELSUR-muestras/arte (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- "Visita guiada temática "Por ella misma - Eugenia Belín Sarmiento", en el Museo Histórico Sarmiento". www.cultura.gob.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-03-10.

External links

- Belin Sarmiento's grave in La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires