Examining magistrate

In an inquisitorial system of law, the examining magistrate (also called investigating magistrate, inquisitorial magistrate, or investigating judge), is a judge who carries out pre-trial investigations into allegations of crime and in some cases makes a recommendation for prosecution. The exact role and standing of examining magistrates varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction; common duties and powers of the examining magistrate include overseeing ongoing criminal investigations, issuing search warrants, authorizing wiretaps, making decisions on pretrial detention, interrogating the accused person, questioning witnesses, examining evidence, and compiling a dossier of evidence in preparation for trial. Examining magistrates have an important role in the French judiciary, and are also a feature of the Spanish, Dutch, Belgian and Greek criminal justice systems, although the extent of the examining magistrate's role has generally diminished over time. Several countries, including Switzerland, Germany, Portugal, and Italy, have abolished the position of examining magistrate outright.

Role and description

John Henry Merryman and Rogelio Pérez-Perdomo have described the examining magistrate's role in civil-law systems as follows:

The typical criminal proceeding in the civil law world can be thought of as divided into three basic parts: the investigative phase, the examining phase (the instruction), and the trial. The investigative phase comes under the direction of the public prosecutor, who also participates actively in the examining phase, which is supervised by the examining judge. The examining phase is primarily written and is not public. The examining judge controls the nature and scope of this phase of the proceeding. The examining judge is expected to investigate the matter thoroughly and to prepare a complete written record so that by the time the examining stage is complete, all the relevant evidence is in the record. If the examining judge concludes that a crime was committed and that the accused is the perpetrator, the case then goes to trial. If the judge decides that no crime was committed or was that the crime was not committed by the accused, the matter does not go to trial.[1]

Comparison to common-law systems

The role of the examining magistrate is important in civil-law jurisdictions such as France, which have an inquisitorial system. In contrast, common-law jurisdictions such as England and the United States have an adversarial system and lack a comparable official.[2][3] Frequent close interaction with police and prosecutors "may well condition examining magistrates to favor the long-term interests of regular participants over those of the accused."[4] This problem also affects common-law jurisdictions, although it has been noted that "in the United States, the focus of concern has been the independence of counsel for the defense, while in France, concern focuses on the independence of the examining magistrate."[5]

The examination phase has been described as "the most controversial aspect of criminal procedure" in civil-law jurisdictions because of "[t]he secrecy and length of the proceedings, the large powers enjoyed by examining magistrates" and "the possibility for abuse inherent in the power of the individual magistrate to work in secret and to keep people incarcerated for long periods."[6] Some commentators, however, have compared the examining magistrate's role favorably to that of the grand jury in common-law systems. Scholar George C. Thomas III finds that while the grand jury as it exists in U.S. law is an effective investigative function, it lacks the screening functions that the French system has. Thomas notes that under U.S. Supreme Court precedent, U.S. prosecutors are not obliged to present exculpatory evidence to grand juries, and as a result grand jurors hear only evidence from the prosecution; by contrast, under the French system, the French examining magistrate operates as an investigator, and the indicting chamber acts as a screening body expressly responsible for seeking the truth.[7]

By country

Use of the examining magistrate has declined in Europe over time.[8] Spain, France, Croatia, the Netherlands, Belgium and Greece are among the countries to retain the practice, and in all of these nations the examining magistrate's role has been diminished, with a general trend of restricting the examining magistrate's involvement to only "serious crimes or sensitive cases" or having the examining magistrate share responsibility with the public prosecutor.[9][10] Switzerland, Germany, Portugal, and Italy have all abolished the examining-magistrate system.[11][12]

History

In France, the investigative judge (juge d'instruction, "judge of inquiry") has been a feature of the judicial system since the mid-19th century, and the preliminary investigative procedure has been a part of the judicial system from at least the 17th century.[13] The sweeping powers traditionally entrusted to the juge d'instruction were so broad that Honoré de Balzac called the examining magistrate "the most powerful man in France" in the 19th century.[14] In a celebrated although exaggerated passage, Balzac wrote that "No human authority, neither the king nor the minister of justice nor the prime minister can intrude on the power of the examining magistrate, no one can stop him, nobody gives him orders. He is sovereign, obeying only his conscience and the law."[15]

Later, however, the authority of the examining magistrates in France diminished in a series of reforms.[16] In 1985, French justice minister Robert Badinter proposed limiting the examining magistrate's role in making custody decisions; Badinter's successor, Albin Chalandon made the same proposal two years later. In 1990, Justice Minister Pierre Arpaillange convened a Human Rights Commission (Justice Penale et Droits de l'Homme), led by the legal scholar Mireille Delmas-Marty.[17] The commission concluded that France's criminal procedure code violated human rights standards,[18] noting that the examining magistrate combined investigative and judicial powers in a single person.[19] The commission proposed a package of due process reforms, including the abolition of the post of examining magistrate and the creation of a "liberty judge" (juge des libertés) in its place. Under the proposed system, the prosecutor and the police would have sole responsibility for conducting the investigation, and the liberty judge would be charged with overseeing pre-trial investigations.[20]

This proposal prompted an outcry from the conservative judiciary, as well as from scholars and the media; "in the context of repeated investigations of Socialist Party officials, the proposition appeared self-interested."[21] Less extensive reforms were adopted instead; legislation coming into effect in 1994 provided a right to counsel for persons in police custody (garde à vue), and also transferred the decision on bail and pretrial detention "to a team of magistrates not involved in the particular case." Almost immediately, however, opponents of the reforms mobilized, upset with the substantial changes to historic French practice; several magistrates resigned in protest. The new minister of justice, Pierre Méhaignerie, pledged repeal, and the reforms were reversed in August 1993, when a new law repealed the right to have counsel at the beginning of police detention (but retained the right to have counsel after 20 hours of detention); restored "the powers of the 'solitary' examining magistrate involved in the case to bail or remand"; and again restricted the accused's access to the investigative dossier.[22]

Reforms resumed in 2000, with the enactment of the Guigou Law, following the issuance of the report of the Truche Commission and a proposal for revision of the French code of criminal procedure by Michèle-Laure Rassat.[23] Among other reforms, the 2000 law abolished the power of the examining magistrate to remand defendants into custody and created a new specialized judicial officer, the judge of liberty and detention (juge des libertés et de la détention) to make these determinations.[24]

Renewed calls for further reform to abolish or diminish the powers of the French examining magistrate intensified after a series of botched investigations,[25] including what became known as the Outreau scandal; in that case, more than a dozen people near Boulogne were wrongfully imprisoned (and about half wrongfully convicted) on false charges of child abuse after a flawed investigation by an inexperienced juge.[26][27] In 2009 and 2010, President Nicolas Sarkozy unsuccessfully attempted to abolish the post of examining magistrate as part of a broader package of legal reforms.[28][29]

Today

Today, examining magistrates (juges d'instruction) are one of four types of French magistrates, the others being trial judges (magistrats de siège), public prosecutors (magistrats debout), and policymaking and administrative magistrates at the Ministry of Justice.[30] Each juge d'instruction is appointed by the president of France upon the recommendation of the Ministry of Justice and serves renewable three-year terms.[31] Magistrates "can move between these four categories, and their career prospects may be subject to the political interests of the government (although promotions must be approved by a high council of the magistrature chaired in the past by the President of the Republic and now by the president of the cour de cassation)."[32] This arrangement has prompted criticism on the ground that the judiciary is not fully independent of the government.[33]

In 1996, political scientist Herbert Jacobs described the still-extensive powers and authority of the examining magistrate:

The examining magistrate ... is responsible for assuring the quality of the investigation that underlies the prosecution, [and] enjoys sweeping powers. In serious cases the magistrate directs the investigation personally, ordering any potentially relevant witnesses to appear and authorizing searches of premises, seizure of financial records, examination by experts and viewings of physical evidence as he or she sees fit. The examining magistrate can delegate some investigatory decisions to police, but the responsibility lies ultimately with the magistrate.[34]

Examining magistrates initiate an investigation upon an order of the procureur (public prosecutor), or upon the request of a private citizen. The juge d'instruction may issue search warrants, order the seizure of necessary evidence, compel witnesses to appear and give evidence, and request expert testimony; at an investigative hearing, the judge may have witnesses confront each other or the accused.[35] They may also authorize wiretaps.[36] At a later plenary hearing in open court, the investigative judge may issue an order of non-lieu ("no case") or, if the evidence is sufficient, will commit the case to the trial court. Charges of a serious misdemeanor or lesser felonies go to the criminal court directly. In contrast, major felonies are referred to the Court of Appeal for the pretrial hearing. The Court of Appeal decides whether to approve the juge's recommendation, and if it does the case is turned over to the Assize Court.[37] Examining magistrates are not involved at trials, although, in France, criminal trials are "in many respects a continuation of the pretrial investigation" with the trial judge acting as the leading figure in the examination of witnesses.[38]

In the year 2000, only about 7% of criminal investigations in France were directed by a juge d'instruction.[39] By 2010, that number had declined further to 4%, with police overseeing the rest.[40] Notably, in 2002, there were 562 investigating magistrates in France, with some 60,000 investigations ongoing at any given moment, so caseloads were large and individual attention to each was difficult.[41] Nevertheless, examining magistrates "are seen as important, independent arbiters, examining the most sensitive and serious allegations."[42] A few examining magistrates, such as Renaud Van Ruymbeke, Thierry Jean-Pierre, and Éric Halphen have become widely known for their investigations into corruption and political scandals; such figures have investigated high-level government officials, including prime ministers, and made widely publicized visits to the headquarters of the major French political parties, reflecting their broad powers.[43]

In France, many magistrates belong to trade unions. About 60% belong to the Union syndicale des magistrats (USM), which is center-right, while about 30% belong to the leftist Syndicat de la Magistrature (SM). The unions represent the interests of magistrates, but by French law are barred from striking.[44]

Spain

In Spain, a juez de instrucción is an examining judge,[45] and a juzgado de instrucción is the office of an examining judge.[46] Each investigating judge is responsible for investigating "all kind of criminal cases committed in his district, except those cases that fall under the jurisdiction of the National Court (Audiencia Nacional) or where another court has jurisdiction ratione personae."[47] In addition to investigating crimes of all sorts, "the investigating judges are competent to try petty offense cases."[48]

Among the most famous Spanish investigating judges was Baltasar Garzón, a polarizing figure known for investigating high-profile corruption and human rights cases. Garzón was known for invoking the doctrine of universal jurisdiction to issue an international arrest warrant for Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, leading to his apprehension in London in 1998. Garzón also gained attention for overseeing an inquiry into atrocities committed during the Spanish Civil War (despite a 1977 amnesty act) and human rights abuses committed during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. Garzón was convicted of illegal wiretapping in 2012 and was suspended from the bench for 11 years.[49]

Andorra

The small European nation of Andorra has investigating magistrates; in 2018, for example, an investigating magistrate in the country issued indictments against 28 people, including former Venezuelan officials, on charges of money laundering.[50]

Belgium and the Netherlands

Both Belgium and the Netherlands retain the examining judge in some cases; examining judges investigate in 5% of cases in Belgium and 2% of cases in the Netherlands.[51]

In Belgium, criminal proceedings are usually initiated by the public prosecutor (Procureur des Konings or procureur du roi), who typically decides whether to issue a summons to a suspect ordering him or her to appear in court. However, in "more serious or complicated cases" the prosecutor can defer to matter to the examining magistrate (onderzoeksrechter or juge d'instruction), who is an independent judge and member of the tribunal of first instance (Rechtbank van eerste aanleg or Tribunal de première instance).[52] The onderzoeksrechter has the power to question suspects, but not under oath; he or she may also question witnesses, issue search warrants, and issue detention orders. The onderzoeksrechter generates a report on the outcome of the investigation and then refers it to the raadkamer, an arm of the court, to decide whether to dismiss the case, allow it to proceed, or (in certain circumstances) to refer it to another court.[53] The role of the onderzoeksrechter role is unusual, because he or she is simultaneously a judge and an officer of the police judiciaire.[54]

In the Netherlands, the position of examining magistrate has existed since 1926, and the powers of the office were strengthened in 1999.[55] Dutch public prosecutors are charged with supervising criminal investigations and ensuring the "legitimacy, fairness and overall integrity" of the investigation and pretrial proceedings.[56] In addition to their investigative role,[57] examining magistrate is also charged with making determinations as to the lawfulness of arrests and as to pretrial detention.[58] The examining magistrate specifically reviews the public prosecutor's request to use some intrusive special investigative techniques when the prosecutor requests the magistrate to do so.[59] For the most intrusive modes of investigation, such as wiretapping or other telecommunication intercepts, public prosecutors must secure the approval of the examining magistrate.[60][61]

Latin America

In Latin America, the investigative (sumario or instrucción) phase of a criminal prosecution was historically overseen by an examining magistrate, preceding the trial (plenario) phase.[62][63] In the first phase, an examining magistrate interviewed the witnesses, questioned the accused, examined evidence, and created a dossier before making a recommendation to the trial judge as to whether the defendant should be discharged or tried.[64] Formerly, in Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela, "no distinction was made between the examining magistrate, who is responsible for the investigation, and the judge, who issues the rulings. This distinction was considered very important in Europe, where these functions were separated to promote the impartiality of the court."[65] In Chile, for example, examining magistrates formerly had the "triple role" of overseeing the investigation, rendering a verdict, and passing a sentence.[66]

By the end of the 20th century, most Latin American countries followed Germany in eliminating the examination phase.[67] In 1998, Venezuela enacted a legal reform that ended the secrecy of the sumario phase and bolstered the ability of accused persons to prepare a defense.[68] Beginning in 2002, Chile began to incorporate more adversarial aspects into its inquisitorial system, and this reform was implemented fully by 2005.[69] The transition to a separation of judicial and investigative roles meant that public prosecutors (fiscales) obtained many responsibilities that were historically performed by investigative magistrates.[70] However, investigations in past human rights abuses in Chile have continued to use investigative magistrates at the first stage.[71]

Greece

Greece, which follows a French-style legal system, has retained the investigative magistrate. In Greece, the investigative magistrate interviews witnesses, reviews the evidence, and refers cases to the public prosecutor, who makes the ultimate charging decision.[72] Greek investigative magistrates can also issue arrest warrants.[73]

Italy

Italy abolished the examining magistrate in 1989, as part of a broader overhaul of the Italian Code of Criminal Procedure.[74] The reform transferred the investigative functions of the examining magistrate to public prosecutors,[75] who in Italy are also considered judges.[76] The reform transferred the oversight functions of examining magistrates to newly created judges of the preliminary investigation with specified duties, including the issuance of search warrants, the authorization of wiretaps, and the decision on pretrial detention.[77] The replacement of examining magistrates was not the only element of the 1989 reform that "marked a departure from the inquisitorial French tradition and partly subscribed to adversarial assumptions"; the code revision introduced cross-examination and negotiation between the parties, although it preserved some elements of the continental legal tradition.[78]

Switzerland

Before 2011 Switzerland had four different models of inquiry: examining magistrate models I and II (Untersuchungsrichtermodell) and public prosecutor models I and II (Staatsanwaltschaftsmodell).[79] Different cantons of Switzerland used different models.[80] Under "examining magistrate model I" an independent examining magistrate directed the police investigation directly, and the public prosecutor was only a party in the case.[81] Under "examining magistrate model II" the examining magistrate and the public prosecutor jointly directed pre-trial proceedings; "the examining magistrate acted not independently, but was bound by the public prosecutor's instructions."[82] The "public prosecutor model I" followed the multiple-stage French system, in which (1) the public prosecution first directed the investigation by judicial police before transferring the matter to the independent examining magistrate; (2) the examining magistrate conducted examination independent of the prosecutor; and (3) at the end of the examining magistrate's inquiry, the case was returned to the public prosecutor, who made the ultimate decision on "whether to charge or discontinue the case."[83] Finally, under "public prosecutor model II" the examining magistrate was absent altogether and the public prosecutor being the "master of preliminary proceedings" responsible for conducting the investigation and examination, making the decision of whether or not to charge, and prosecuting the case.[84]

When the Swiss Code of Criminal Procedure came into effect in 2011, Switzerland adopted the latter model nationwide, abolished the position of examining magistrate that had previously existed in some cantons.[85]

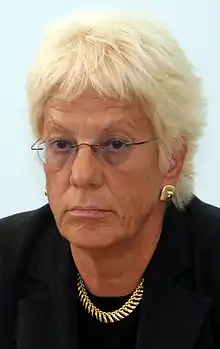

One prominent Swiss investigative magistrate was Carla Del Ponte, who became prominent for her investigations into Sicilian Mafia crime in Switzerland. Del Ponte was later appointed public prosecutor and then federal attorney general of Switzerland, before becoming chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.[86]

Elsewhere

Poland historically had examining magistrates; Polish examining magistrate Jan Sehn investigated the Nazi atrocities at Auschwitz in preparation for the Auschwitz trials.[87] However, in 1949, the Polish judiciary was restructured along Soviet lines, and the position of investigating magistrate was eliminated.[88]

West Germany abolished the examining magistrate at the end of 1974.[89][90] Portugal abolished the examining magistrate in 1987.[91]

In popular culture

The 1969 film Z stars an examining magistrate based on Christos Sartzetakis.[92]

Notes

- Merryman & Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 130

- Jacob 1996, p. 213

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2002

- Jacob 1996, p. 212

- Jacob 1996, pp. 212–13

- Fairchild 1993, p. 128

- Thomas III 2008, p. 203

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 59

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 59

- Fenyk 2000, p. 42

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 60

- Fenyk 2000, p. 42

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2002

- Gilliéron 2014, pp. 50, 319

- Anderson 2011, pp. 167–68

- Gilliéron 2014, pp. 50, 319

- Vogler 2005, p. 148

- Vogler 2005, p. 148

- Salas 2002, p. 498

- Vogler 2005, p. 148

- Vogler 2005, p. 148

- Vogler 2005, p. 149

- Vogler 2005, p. 149

- Vogler 2005, p. 149

- Lichfield 2002

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 60

- Samuel 2009

- Samuel 2009

- Saltmarsh 2010

- Anderson 2011, p. 167

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2002

- Anderson 2011, p. 168

- Anderson 2011, p. 168

- Jacob 1996, p. 213

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2002

- Saltmarsh 2010

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2002

- Jacob 1996, pp. 213–14

- Fenyk 2000, p. 42

- Saltmarsh 2010

- Lichfield 2002

- Saltmarsh 2010

- Cole 2015

- Antoine Garapon & Harold Epineuse, "Judicial Independence in France" in Judicial Independence in Transition (ed. Anja Seibert-Fohr: Springer, 2012), p. 295.

- Bachmaier & García 2010, p. 31

- Truscott & García 1998, p. 169

- Bachmaier & García 2010, p. 31

- Bachmaier & García 2010, p. 32

- Minder & Simons 2012.

- Aritz Parra, Andorra charges Venezuelan ex-officials for money laundering, Associated Press (September 13, 2018).

- Fenyk 2000, p. 42

- Châtel 1982, p. 189

- Châtel 1982, pp. 189–90

- Pesquié 2002, p. 106

- Ballin 2012, pp. 101–02

- Ballin 2012, p. 101

- Franken 2012, pp. 38–40

- Franken 2012, p. 36

- Ballin 2012, p. 101

- Ballin 2012, p. 101

- Franken 2012, pp. 37–38

- Karst & Rosenn 1975, p. 56

- Mauricio & Pérez-Perdomo 2003, pp. 72–73

- Karst & Rosenn 1975, p. 56

- Mauricio & Pérez-Perdomo 2003, p. 73

- Skaar 2011, p. 127

- Merryman & Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 130

- Ungar 2002, p. 59

- Skaar 2011, p. 127

- Collins 2010, p. 123

- Skaar 2011, p. 127

- Veremēs & Dragoumēs 1995, p. 102

- Kitsantonis 2017

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 127

- Salas 2002, p. 495

- Salas 2002, p. 498

- Maffei & Merzagora Betsos 2010, p. 173

- Maffei & Merzagora Betsos 2010, p. 173

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 57

- Gilliéron 2014, pp. 57–59

- Gilliéron 2014, pp. 57–58

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 58

- Gilliéron 2014, pp. 58–59

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 59

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 59

- Del Ponte 2009

- Langbein 2005, pp. 8, 314

- Paczkowski 2010, p. 231

- Gilliéron 2014, p. 319

- Fenyk 2000, p. 42

- Fenyk 2000, p. 42

- The New York Times Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made (Revised and updated ed.). Macmillan. 2004. p. 145. ISBN 9780312326111.

References

Books

- Anderson, Malcolm (2011). In Thrall to Political Change: Police and Gendarmerie in France. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199693641. OCLC 906084292.

- Bachmaier, Lorena; García, Antonio del Moral (2010). Criminal Law in Spain. Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 9789041132956. OCLC 963549186.

- Ballin, Marianne F.H. Hirsch (2012). Anticipative Criminal Investigation: Theory and Counterterrorism Practice in the Netherlands and the United States. T.M.C. Asser Press. ISBN 9789067049481. OCLC 876005886.

- Châtel, Marc (1982). John A. Andrews (ed.). Human Rights and Belgian Criminal Procedure at Pre-Trial and Trial Level. Human Rights in Criminal Procedure: A Comparative Study. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9024725526. OCLC 848268259.

- Cole, Alistair (2015). French Politics and Society (2d ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781317376958. OCLC 984993770.

- Collins, Cath (2010). Post-transitional Justice: Human Rights Trials in Chile and El Salvador. Penn State University Press.

- Dammer, Harry R.; Albanese, Jay S. (2011). Comparative Criminal Justice Systems (4th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780495812708. OCLC 741932781.

- Del Ponte, Carla (2009). Madame Prosecutor: Confrontations with Humanity's Worst Criminals and the Culture of Impunity (English-language ed.). Other Press. ISBN 9781590515372.

- Fenyk, Jaroslav (November 2000). "Reflections on Development of the Authorities of Public Prosecution and on Importance of Some Principles of Criminal Procedure" in the European Democracies, in What Public Prosecution in Europe in the 21st Century. Proceedings of the Pan-European Conference, Strasbourg, 22–24 May 2000, Council of Europe. ISBN 9287144729. OCLC 604386710.

- Fairchild, Erika (1993). Comparative Criminal Justice Systems. Wadsworth. ISBN 9780534129965. OCLC 26400250.

- Franken, Stijn (2012). M.S. Groenhuijsen; Tijs Kooijmans (eds.). "The Judge in the Pre-Trial Investigation" in The Reform of the Dutch Code of Criminal Procedure in Comparative Perspective. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9789004232594. OCLC 812174481.

- Gilliéron, Gwladys (2014). Public Prosecutors in the United States and Europe: A Comparative Analysis with Special Focus on Switzerland, France, and Germany. Springer International. ISBN 9783319045030. OCLC 918792441.

- Jacob, Herbert (1996). Courts, Law, and Politics in Comparative Perspective. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300063790. OCLC 318372322.

- Karst, Kenneth L.; Rosenn, Keith S. (1975). Law and Development in Latin America: A Case Book. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520029552. OCLC 848182780.

- Langbein, Hermann (2005). People in Auschwitz. Translated by Harry Zohn. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469628370. OCLC 919104117.

- Maffei, Stefano; Merzagora Betsos, Isabella (2010). Graeme R. Newman (ed.). "Italy" in Crime and Punishment Around the World. 4 (Europe). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313351334. OCLC 878812767.

- Merryman, John Henry; Pérez-Perdomo, Rogelio (2007). The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Europe and Latin America (3d ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503606814. OCLC 1029071232.

- Mauricio, Duce; Pérez-Perdomo, Rogelio (2003). H. Hugo Frühling; Joseph S. Tulchin; Heather Golding (eds.). "Citizen Security and Reform of the Criminal Justice System in Latin America" in Crime and Violence in Latin America: Citizen Security, Democracy, and the State. Woodrow Wilson Center Press/Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801873836. OCLC 981363951.

- Pesquié, Brigitte (2002). Mireille Delmas-Marty; J.R. Spencer (eds.). "The Belgian System" in European Criminal Procedures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521678483. OCLC 850972090.

- Paczkowski, Andrzej (2010). Spring Will Be Ours: Poland and the Poles from Occupation to Freedom. Translated by Jane Cave. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271023083. OCLC 59286551.

- Salas, Denis (2002). Mireille Delmas-Marty; J.R. Spencer (eds.). "The Role of the Judge" in European Criminal Procedures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521678483. OCLC 850972090.

- Skaar, Elin (2011). Judicial Independence and Human Rights in Latin America: Violations, Politics, and Prosecution. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Terrill, Richard J. (2016). World Criminal Justice Systems: A Comparative Survey (9th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 9781138940864. OCLC 952931856.

- Thomas III, George C. (2008). The Supreme Court on Trial: How the American Justice System Sacrifices Innocent Defendants. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472034833. OCLC 741563460.

- Truscott, Sandra; García, Maria (1998). Dictionary of Contemporary Spain. Routledge. ISBN 9781136595028. OCLC 962061312.

- Ungar, Mark (2002). Elusive Reform: Democracy and the Rule of Law in Latin America. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Veremēs, Thanos; Dragoumēs, Markos (1995). "Justice, Administration of" in Historical Dictionary of Greece. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810828889. OCLC 468714464.

- Vogler, Richard (2005). A World View of Criminal Justice (Routledge 2016 ed.). Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754624677. OCLC 61425669.

Other works

- "Juge d'instruction". Encyclopædia Britannica. April 26, 2002.

- Samuel, Henry (January 7, 2009). "Nicolas Sarkozy to abolish controversial French magistrate". The Telegraph. ISSN 2059-7487. OCLC 49632006. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017.

- Saltmarsh, Matthew (July 5, 2010). "Sarkozy's Legal Reforms Run Into Obstacles". The New York Times. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 2018-08-28. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- Lichfield, John (March 15, 2002). "Why the French are growing envious of Britain's justice system". The Independent. ISSN 0951-9467. OCLC 185201487.

- Minder, Raphael; Simons, Marlise (February 9, 2012). "Prominent Rights Judge Is Convicted in Spain". The New York Times. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522.

- Kitsantonis, Niki (October 28, 2017). "Greek Police Arrest Suspect in Letter Bomb Attacks". The New York Times. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522.