Eysturoyartunnilin

The Eysturoyartunnilin (in English the Eysturoy Tunnel, earlier known as the Skálafjarðartunnilin) is a large undersea road tunnel under the Tangafjørður sound in the Faroe Islands, connecting the island of Streymoy to the island of Eysturoy. It also crosses the southern part of Skálafjørður, and connects the towns of Runavík on the eastern side and Strendur on the western side of the fjord, and includes the world's first undersea roundabout in the middle of the network.

Construction site at Hvítanes, 2017, overlooking the Tangafjørður strait under which the tunnel is situated. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Skálafjørður and Tórshavn, Faroe Islands |

| Status | In operation |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | 2016 |

| Opened | 19 December 2020 |

| Owner | The Faroese Government |

| Operator | P/F Eystur- og Sandoyartunlar |

| Traffic | Automotive |

| Toll | Yes |

| Vehicles per day | estimated 6,000 |

| Technical | |

| Length | 11,238 m (36,870 ft) |

| No. of lanes | 2 |

| Operating speed | 80 km/h (50 mph) |

| Highest elevation | 21.6 m (71 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | −189.0 m (−620.1 ft) |

| Width | 10.5 m |

| Grade | 5.0 % (max.) |

It is the largest ever infrastructure project in the Faroe Islands.[1] Altogether, the three-branch sub-sea tunnel measures 11.24 kilometres (6.98 mi) long, including the roundabout. Construction costs are estimated to be around a billion DKK.[7] The roundabout features artwork, including large sculptures and light effects.[2] The tunnel opened for traffic on 19 December 2020.[3][2]

History

The idea for the Eysturoyartunnilin emerged during the construction of the Vágatunnilin and Norðoyatunnilin, opened in 2002 and 2006 respectively, which heralded a new look on domestic transport and regional development. In 2006, the private company P/F Skálafjarðartunnilin was founded to build this tunnel.[4] Due to the financial crisis, it took the stakeholders several years to materialize the plans and get political support.[5] The tunnel was included in the 2012 national mobility plan, which abandoned the name Skálafjarðartunnilin and thereafter exclusively named it Eysturoyartunnilin.[6] In June 2013, another private company, P/F Eysturoyartunnilin, was established in order to pursue a deal between the Faroese national government, the Faroese insurance company LÍV and the Danish-owned Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP). CIP made secret arrangements with the Faroese minister for transport, Kári P. Højgaard, who had to resign in early September as this came out. This led to a small political crisis. In 2015, after the outcomes of an official inquiry, the cabinet of Kaj Leo Johannesen had to call for early elections.[7][8] Both P/F Skálafjarðartunnilin and P/F Eysturoyartunnilin were liquidated in 2015, after circa two years of inactivity.[9][10] Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the political crisis of 2013, a special commission drafted a proposal for a public rather than private solution.[11] This proposal was supported by all parties and led in 2014 to the establishment of a public company, P/F Eystur- og Sandoyartunlar (in short 'EStunlar' or EST).[12][13] This company, owned entirely by the Ministry of Transport, builds, owns and manages both the Eysturoyartunnil and the Sandoyartunnil. NCC was contracted to carry out the construction works.

Further reading

- Theme about the Eysturoy tunnel by the National Broadcasting Service of the Faroe Islands: http://kvf.fo/tema/skalafjardartunnilin

- Documentary by KVF: Skálafjarðartunnilin - kosta hvat tað kosta vil

Construction

On 8 November 2016, a deal was struck with the Scandinavian construction company NCC to construct the Eysturoy tunnel as well as the Sandoy tunnel. The contract for both tunnels is for 2,073 million DKK, whilst the overall cost for both tunnels is estimated at around 2,600 million DKK.[14]

The drilling of the tunnel itself started on 21 February from the Strendur side and on 27 April 2017 from the Hvítanes side. The Strendur team reached the underwater roundabout section on 4 December 2017,[15] at which point 3,059 metres had been dug from both sides combined. With the first leg and roundabout completed, a third drilling team started, with two teams on the Hvítanes-roundabout leg working towards each other (which met underwater on 7 June 2019) and one from the roundabout to Saltnes. The last blast was shot on 7 June 2019, after which a number of months was used for tarmacking, cabling, installing emergency facilities and signposting. Meanwhile, NCC moved the drillsets to the Sandoyartunnilin, which started on 27 June 2019.

While the expected opening date was 1 December 2020, due to technical delays and COVID-19 this was postponed to 19 December 2020.[16]

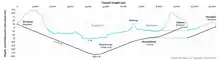

Specifications

The tunnel is a two-laned undersea tunnel that has three tubes which meet at an underwater roundabout, 72.6 metres below the surface of the Skálafjørður fjord. The tunnel is 2,153 metres long from the entrance at Rókini in Saltnes to the roundabout, and the distance from Sjógv at Strendur to the roundabout is 1,625 metres. The main branch from Tórshavn to the roundabout measures 7,460 metres and resurfaces by the village of Hvítanes.[17] This results in an overall road length of 11.238 kilometres,[14] making it currently the 2nd-longest sub-sea road tunnel in the world, surpassed only by the Ryfast tunnel at Stavanger in Norway. The roundabout is the world's first sub-sea roundabout.[18]

In order to increase safety, no incline in the tunnel is steeper than five per cent, and the lowest point is 189 metres (620 ft) below the water's surface.[19][2]

Tolls

Construction costs for the tunnel are being recouped through toll fees. Tolls start at 75 DKK for small cars (up to 3,500 kilograms (7,700 lb)) between Tórshavn and Eysturoy, and 25 DKK for local traffic between Saltnes (near Runavík) and Strendur. This price is for people who have a subscription (hald). Without subscription the price is 175 DKK between Eysturoy to Streymoy and 125 DKK between the two arms of Skálafjørður.[20] Tolls are levied for travel in both directions, unlike the Vágatunnilin and Norðoyatunnilin, which only charge tolls one way. Tolls for the Eysturoyartunnilin are coupled with the construction and operating costs of Sandoyartunnilin, which would not have been feasible as a project on its own. Experience from the two existing sub-sea tunnels suggests that traffic in the tunnel is likely to be greater than originally expected, so a growing number of cars should ensure stable funding.[21][22]

Art in the tunnel

The roundabout is fitted with metal artwork by the renowned Faroese artist Tróndur Patursson, as well as lighting effects.[2] The artwork is an 80-metre (260 ft) piece which he custom-made for the tunnel, featuring a combination of human silhouettes and light effects. The metal plates will be allowed to oxidise and change colour. The Norðoyatunnilin, which opened in 2006, also includes some of Patursson's light art.[23]

Each tunnel portal features a sequence of freestanding concrete and lit arches, as landmarks.

Impact

When the tunnel opened in December 2020, it significantly reduced travel times to the capital. The tunnel shortened the travel distance from Tórshavn to Runavík/Strendur from 55 kilometres (34 miles) to 17 kilometres (11 miles). The 64-minute drive is cut down to 16 minutes. The drive from Tórshavn to Klaksvík was reduced from 68 minutes to 36 minutes.[17] Similar to the impacts of the two existing sub-sea tunnels, an intensification of traffic, interaction and regional integration is expected to result from the increased accessibility, on both the local, regional and national scale.[24] On the Eysturoy side of the tunnel house prices increased by 31% between 2019 and 2020 and have doubled between 2015 and 2020.[25][26]

Strandfaraskip Landsins changed its bus route network in response to the tunnel's opening. Trunk route 400 connecting Klaksvík to Tórshavn left its old route via Sundalagið. Instead, it drives mainly via Runavík and occasionally via Strendur, saving about 25 minutes per trip. A new route 450 has been established to connect Sundalagið to the transfer sites at Kollafjørður (Effo) and Søldarfjørður, whence there are connections to Tórshavn and Klaksvík respectively. Route 440 Strendur-Toftir continues to use the route around Skálafjørður and does not make use of the tunnel.[27][28]

The national government and Runavik municipality agreed on the construction of a bypass between the tunnel mouth and the town limits of Glyvrar, in order to alleviate the increasing traffic through the town streets once the tunnel has opened. This road, named Fjøruvegurin (foreshore road), is going to be built on the shoreline.[29] A proposed highway between Hvítanes and Tórshavn, Innkomuvegurin, remains unsettled as of December 2020.[30][31][32]

The opening

The opening of the tunnel for general traffic was on 19 December 2020, which was 18 years and 9 days after the opening of the first subsea tunnel in the Faroe Islands, the Vágatunnilin connecting Tórshavn with Vágar Airport. For the Eysturoyartunnilin there was a ceremony with speeches and music before the tunnel opened, which was broadcast live by the Faroese Television KVF.[33] Emergency response vehicles had been allowed to use the tunnel a few months before opening.[34]

It was free of charge to drive through the tunnel from 19 December to 10 January 2021. On 19 December, between the opening at noon and midnight, 14,700 vehicles passed through the tunnel.[35] [36]

See also

References

- "The project". Eystur- og Sandoyartunlar. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Faroe Islands: Inside the undersea tunnel network". BBC News. 4 December 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Tórshavn-Eysturoy tunnel to open before Christmas

- "Document on a reply from Rúni B. Róin and Jan Jakobsen on written questions from Elsebeth M. Gunnleygsdóttir" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- "Timeline of the Eysturoyartunni as of June 2013". Innlendismálaráðið. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- "Samferðsluætlan 2012-2024 - Føroyar Sum Ein Býur". Innlendismálaráðið. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- From, Lars (23 August 2015). "En tunnel, der kom på tværs" (in Danish). Jylllands-Posten. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Rigsombudsmanden på Færøerne (13 August 2015). "Indberetning nr. 4/2015" (PDF) (in Danish). Rigsombudsmanden. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "P/F Skálafjarðartunnilin liquidated". Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- "P/F Eysturoyartunnilin liquidated". 8 August 2015. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- "uppskot til logtingslog um stovnan av partafelagi at reka undirsjovartunlar". 13 December 2013. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- "P/F Eystur- og Sandoyartunlar erected". Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- "Law on the Eysturoy- and Sandoyartunlar". Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- "Sáttmáli undirskrivaður um bygging av... - P/F Eystur- og Sandoyartunlar | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- "Framgongd við boring". Eystur- og Sandoyatunlar (in Faroese). Retrieved 2018-11-10.

- "Eysturoyartunnilin letur møguliga ikki upp fyrr enn tíðliga í 2021". dagur.fo (in Faroese). Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- "The Eysturoy tunnel". Eystur- og Sandoyatunlar. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- "Take a look at the Atlantic's first underwater roundabout!". BBC Newsround. 8 December 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Eysturoyartunnilin gongur skjótt". Ministry of Transport. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- Tunnil.fo - Prísir

- "THE PROJECT". Eystur- og Sandoyatunlar. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- "Hokwerda R, Tunnel Visionary, 2017-09-30.pdf".

- Nielsdóttir, Alda (1 December 2020). "Roundabout in undersea Eysturoy Tunnel to be lit up by huge Tróndur Patursson art piece". local.fo. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- "Hokwerda R, Tunnel Visionary, 2017-09-30.pdf".

- Hammershaimb Christiansen, Ása (16 January 2020). ""Tunnel effect" boosts house prices in Runavík". Kringvarp Føroya (in Faroese).

- "Eysturoyartunnilin gevur hægri sethúsaprísir og størri bústaðarbyrðu". Betri. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- "Ferðaætlan". SSL. Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- "Vit eru klár til tunnilin". ssl.fo. Strandfaraskip Landsins. 18 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Avtala um Fjøruvegin

- "Innkomuvegurin". landsverk.fo. Landsverk. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Biðja landsstýrið skunda sær". Kringvarp Føroya (in Faroese). Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- Mortensen, Heðin (10 December 2020). "Innkomuvegurin aftur jólatrøll". in.fo (in Faroese). Sosialurin. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Johannesen, Johnsigurd (19 December 2020). "KvF sendir úr Eysturoyartunlinum í morgin". kvf.fo. Kringvarp Føroya. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Neyðsynjarakfør gjøgnum Eysturoyartunnilin". Kringvarp Føroya (in Faroese). Retrieved 2020-09-14.

- Lindenskov, Eirikur (20 December 2020). "14.700 bilar koyrdu í tunlinum í gjár". in.fo. Sosialurin. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Nielsdóttir, Alda (20 December 2020). "Toll free until 10 January". in.fo. Dagur. Retrieved 20 December 2020.