Fetal movement

Fetal movement refers to motion of a fetus caused by its own muscle activity. Locomotor activity begins during the late embryological stage and changes in nature throughout development. Muscles begin to move as soon as they are innervated. These first movements are not reflexive, but arise from self-generated nerve impulses originating in the spinal cord. As the nervous system matures, muscles can move in response to stimuli.[1]

Generally speaking, fetal motility can be classified as either elicited or spontaneous, and spontaneous movements may be triggered by either the spine or the brain. Whether a movement is supraspinally determined can be inferred by comparison to movements of an anencephalic fetus.[2]

This article primarily deals with voluntary and reflex movements. Ages are given as age from fertilization rather than as gestational age.

Some sources contend that there is no voluntary movement until after birth.[3] Other sources say that purposive movement begins months earlier.[4] 3D ultrasound has been used to create motion pictures of fetal movement, which are called "4D ultrasound".[5]

Movement during development

Embryonic stage

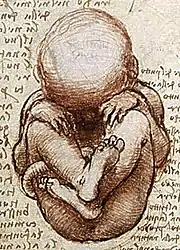

Even before the fetal stage begins, a six-week-old human embryo can arch its back and neck.[6] By seven weeks, movement in the arms and legs can be detected by ultrasound.[6]

Fetal stage

The parts of the fetal brain that control movement will not fully form until late in the second trimester, and the first part of the third trimester.[7] Control of movement is limited at birth, and purposeful voluntary movements develop during the long period up until puberty.[8] According to an overview produced by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, purposive movement begins at about 18 weeks, gradually replacing reflex movements, and purposeful voluntary movements then develop further after birth.[4]

In these early movements, the limbs move together; they begin to move independently by the ninth week as the controlling neurons in the spinal cord develop.[9] At week 11, the fetus can open its mouth and suck its fingers; at week 12, it begins to swallow amniotic fluid.[10]

In addition to sideward bendings of the head, complex and generalized movements occur at the beginning of the fetal stage, with movements and startles that involve the whole body.[11] Movement of hands, hips and knees have been observed at nine weeks,[12] stretches and yawns at ten weeks,[13] and isolated limb movements beginning shortly thereafter.[14]

Second trimester

By about the twelfth week, the fetus is able to kick and curl its toes, and may grasp its feet or scratch itself with its fingernails.[10] It can also move in response to a touch on its skin.[15] Also starting about week 12, the thoracic diaphragm moves up and down as if the fetus were breathing, but this movement disappears about week 16 and does not resume until the third trimester.[16]

Movements such as kicking continue, and the mother usually feels movement for the first time, an event called quickening, during the fifth month.[17] Around this time, limb movements become more complex, with flexing of the joints and ribs. This activity assists with proper joint development.[15] Women who have already given birth have more relaxed uterine muscles that are consequently more sensitive to fetal motion, and for them fetal motion can sometimes be felt as early as 14 weeks.[18]

By about week 21, the fetus begins to develop a regular schedule of movement.[17] The startle reflex is present in half of all fetuses by week 24 and in all fetuses by week 28.[19] Movement is restricted around this time because the fetus has grown so large it has little space for kicking or changing body position.[20]

Variation in activity level

Fetuses aged 14 to 18 weeks show a pronounced circadian rhythm in their activity level, which can be detected both by fetal electrocardiogram and by measuring locomotor activity. Active and quiet periods for the fetus do not correspond to those of the mother; fetuses are most active from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. and again from 7 p.m. to 4 a.m.[21] During the last four to six weeks before birth, most of the fetus's kicking and jabbing movements occur while it is sleeping lightly.[22]

Monitoring fetal movement

After quickening, a pregnant woman may choose to count the number and types of movements she feels her fetus make. This tally is informally known as a kick count. The American Pregnancy Association states that advantages of conducting kick counts range from giving a pregnant woman an opportunity to bond with her baby to reducing the risk of stillbirth; kick counts are especially recommended in high risk pregnancies.[23] However, instructing women to monitor fetal movements is potentially associated with increased maternal anxiety.[24]

To make a kick count, a woman finds a comfortable position, such as sitting upright with her back supported or lying on her left side (which maximizes blood flow to the fetus), and times how long it takes to feel at least ten movements such as kicks, flutters, or rolls. Ideally, ten movements should be felt within two hours,[24] although often that number is reached in a much shorter period.[23] A count of less than ten movements prompts immediate contact with a midwife or maternity unit.[24] 70% of pregnancies with a single episode of reduced fetal movements are uncomplicated.[24]

There is no good evidence to suggest which method of counting fetal movement is best.[25] It was suggested that formal movement counting such as count to 10 or counting movements at a specific time each day was more effective than an undefined method in detecting when the baby was in distress.[25] More research is needed to establish whether counting movements does reduce the rates of stillbirths particularly in countries where resources are not readily available.[25]

In the UK, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists say that if you think your baby has stopped moving or is moving less and you are over 28 weeks pregnant you should contact your midwife. Do not wait until the next day to contact the hospital or midwife.[26]

Notes

- Vaughan 1996, p. 208.

- De Vries, Johanna et al. "Fetal Motility in the First Half of Pregnancy", in Continuity of Neural Functions from Prenatal to Postnatal Life, pages 4 and 63 (1984 Cambridge University Press, edited by Heinz F. R. Prechtl).

- White, Lois. Foundations Of Maternal & Pediatric Nursing, pages 10 and 128 (2004): "By the end of the 12th week, skeletal muscles begin involuntary movements....The newborn may cry and have muscular activity when cold, but there is no voluntary control of muscular activity."

- Becher, Julie-Claire. "Insights into Early Fetal Development". Archived from the original on 2013-06-01. (Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow October 2004): "Purposive movement depends on brain maturation. This begins at about 18 weeks' gestation and progressively replaces reflex movements, which disappear by about 8 months after birth....Reflexes are very different from purposeful voluntary movements which develop during the first year of life."

- Prenatal Image Gallery Index, The Endowment for Human Development (providing numerous 4D ultrasounds that can be viewed online).

- Vaughan, p. 207.

- The development of cerebral connections during the first 20–45 weeks’ gestation. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, Volume 11, Issue 6, Pages 415-422

- Stanley, Fiona et al. "Cerebral Palsies: Epidemiology and Causal Pathways", page 48 (2000 Cambridge University Press).

- Vaughan 1996, pp. 208-209.

- Vaughan 1996, p. 74.

- Prechtl, Heinz. "Prenatal and Early Postnatal Development of Human Motor Behavior" in Handbook of brain and behaviour in human development, Kalverboer and Gramsbergen eds., pp. 415-418 (2001 Kluwer Academic Publishers): "The first movements to occur are sideward bendings of the head....At 9-10 weeks postmestrual age complex and generalized movements occur. These are the so-called general movements (Prechtl et al., 1979) and the startles. Both include the whole body, but the general movements are slower and have a complex sequence of involved body parts, while the startle is a quick, phasic movement of all limbs and trunk and neck."

- Valman HB, Pearson JF (January 1980). "What the fetus feels". Br Med J. 280 (6209): 233–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6209.233. PMC 1600041. PMID 7427089.

Nine weeks after conception...fingers [bend] round an object in the palm of his hand. In response to a touch on the sole of his foot...hips and knees [bend] to move away from the touching object.

- Butterworth, George and Harris, Margaret. Principles of developmental psychology, page 48 (Psychology Press 1994): "stretch and yawn pattern at 10 weeks."

- Prechtl, Heinz. "Prenatal and Early Postnatal Development of Human Motor Behavior" in Handbook of brain and behaviour in human development, Kalverboer and Gramsbergen eds., pp. 415-418 (2001 Kluwer Academic Publishers): "At 9-10 weeks postmenstrual age complex and generalized movements occur... [I]solated movements of one arm or leg emerge 1 week later."

- Vaughan 1996, p. 209.

- Vaughan 1996, pp. 106-107.

- Vaughan 1996, p. 134.

- Van Der Ziel, Cornelia & Tourville, Jacqueline. Big, Beautiful & Pregnant: Expert Advice And Comforting Wisdom for the Expecting Plus-size Woman (Marlowe 2006). Retrieved 2007-02-15.

- Vaughan 1996, p. 160, p. 189.

- Vaughan 1996, p. 190.

- Kintraia et al. 2005.

- Vaughan 1996, p. 138.

- American Pregnancy Association, 2007.

- RCOG release: Reduced fetal movements – New Green-top Guideline from Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Date published: 25/02/2011

- Mangesi, L; Hofmeyr, GJ; Smith, V; Smyth, RM (15 October 2015). "Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD004909. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004909.pub3. hdl:10019.1/104296. PMID 26467769.

- "Reduced Fetal Movements" (PDF). Retrieved 25 April 2016.

References

- "Kick Counts". American Pregnancy Association. July 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- Kintraia PI, Zarnadze MG, Kintraia NP, Kashakashvili IG (March 2005). "Development of daily rhythmicity in heart rate and locomotor activity in the human fetus". J Circadian Rhythms. 3 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1740-3391-3-5. PMC 1079927. PMID 15801976.

- Vaughan, Christopher (1996). How Life Begins: The Science of Life in the Womb. New York: Times Books (Random House). ISBN 978-0-8129-2103-8.