Fifty Bibles of Constantine

The Fifty Bibles of Constantine were Bibles in the original Greek language commissioned in 331 by Constantine I and prepared by Eusebius of Caesarea. They were made for the use of the Bishop of Constantinople in the growing number of churches in that very new city. Eusebius quoted the letter of commission in his Life of Constantine, and it is the only surviving source from which we know of the existence of the Bibles.[1]

Biblical canon

It is speculated that this commission may have provided motivation for the development of the canon lists and that Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus are possible surviving examples of these Bibles.[2] There is no evidence among the records of the First Council of Nicaea of any determination on the canon; however, Jerome, in his Prologue to Judith, makes the claim that the Book of Judith was "found by the Nicene Council to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures".[3]

Requisition

According to Eusebius, Constantine I wrote him in his letter:

I have thought it expedient to instruct your Prudence to order fifty copies of the sacred Scriptures, the provision and use of which you know to be most needful for the instruction of the Church, to be written on prepared parchment in a legible manner, and in a convenient, portable form, by professional transcribers thoroughly practised in their art.[4]

About accomplishing the Emperor's demand:

Such were the emperor's commands, which were followed by the immediate execution of the work itself, which we sent him in magnificent and elaborately bound volumes of a threefold and fourfold form.[5]

This is the usual way in which Eusebius' text is translated, but there are more possibilities, because the phrase "ἐν πολυτελῶς ἠσκημένοις τεύχεσιν τρισσὰ καὶ τετρασσὰ διαπεμψάντων ἡμῶν" has many potential meanings:

- Three or four codices were prepared at a time – Kirsopp Lake and Bernard de Montfaucon;

- Codices were sent in three or four boxes – F. A. Heinichen;

- Codices were prepared in with three or four folios – Scrivener;

- Text of the codices was written in three or four columns per page – Tischendorf, Gebhardt, and Gregory, Kirsopp Lake;

- Codices were sent by threes or fours.

- Some codices contained three gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) but others included four gospels (including John) - Eduard Schwartz.

Athanasius of Alexandria referred to another request of producing Bible manuscripts: "I sent to him volumes containing the holy Scriptures, which he had ordered me to prepare for him."[6][7] Athanasius could have received this request between 337-339.[8]

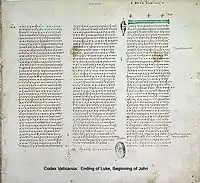

Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus

Constantin von Tischendorf, discoverer of Codex Sinaiticus, believed that Sinaiticus and Vaticanus were among these fifty Bibles prepared by Eusebius in Caesarea. According to him, they were written with three (as Vaticanus) or four columns per page (as Sinaiticus).[9][10] Tischendorf's view was supported by Pierre Batiffol.[11]

Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener rejected Tischendorf's speculation because of differences between the two manuscripts. In Sinaiticus, the text of the Gospels is divided according to the Ammonian Sections with references to the Eusebian Canons, but Vaticanus used the older system of division. Vaticanus was prepared in a format of 5 folios in one quire, but Sinaiticus had 8 folios. According to Scrivener, Eusebian Bibles contained three or four folios per quire (Scrivener used a Latin version of Valesius). Scrivener stated that the Eusebian is unclear and should not be used for a doubtful theory.[12]

Westcott and Hort argued the order of biblical books on the Eusebian list of the canonical books, quoted by Eusebius in "Ecclesiastical History" (III, 25), is different from every surviving manuscript. Probably none of the 50 copies survive today.[13]

Caspar René Gregory believed that Vaticanus and Sinaiticus were written in Caesarea, and they could belong to the Eusebian fifty.[14][15]

According to Victor Gardthausen Sinaiticus is younger than Vaticanus by at least 50 years.[16]

Kirsopp Lake states "copies of three and four columns" is grammatically sound, but there appears not to be good evidence for this technical use of the words. "Sending them by threes of fours" is the most attractive, but there is no evidence that τρισσα can denote "three at a time". Regarding "in three or four columns per page," there is only one known manuscript written in that way – Sinaiticus. Sinaiticus has a curious spelling of the word κραβαττος as κραβακτος; Sinaiticus spells Ισραηλειτης as Ισδραηλειτης, Vaticanus as Ιστραηλειτης; these forms have been regarded as Latin, and they can find in papyri from Egypt. There is no other known Greek district in which these forms were used. The argument for a Caesarean origin of these two manuscripts is much weaker than Egyptian.[17]

According to Heinrich Schumacher, Eusebius instead prepared fifty lectionaries, not Bibles.[18]

Skeat argued that Sinaiticus was a first attempt to produce a full Bible in fulfillment of Constantine's order but was abandoned before completion in favor of a more compact form (then languishing in Caesarea until salvaged in the sixth century), while Vaticanus was one of the fifty Bibles actually delivered to Constantinople.[19]

Kurt Aland, Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman doubt that Sinaiticus and Vaticanus were copied by Eusebius on the Constantine order.[20]

See also

- Differences between codices Sinaiticus and Vaticanus

- Great uncial codices

References

- Eusebius, The Life of the Blessed Emperor Constantine, Bk 4, Ch 36 Constantine's letter of commission

- McDonald & Sanders, pp.414–415

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.: Canonicity: "the Synod of Nicaea is said to have accounted it as Sacred Scripture" (Praef. in Lib.). It is true that no such declaration is to be found in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether St. Jerome is referring to the use made of the book in the discussions of the council, or whether he was misled by some spurious canons attributed to that council"

- Vita Constantini, IV,36

- Vita Constantini, IV,37

- Apologia ad Constantium 4

- Apologia Ad Constantium/Chapter 4

- Elliott, p. 284.

- Novum Testamentum Graece ad Antiquissimos Testes Denuo Recensuit, Tischendorf, Editio Octava Critica Maior, Leipzig 1884, vol. III, p. 348

- Price

- Pierre Batiffol, Codex Sinaiticus, w DB. 1, 1883-1886.

- Scrivener, vol. 1. pp. 118-119.

- Westcott & Hort, p.74.

- Gregory, pp.327, 345

- Gregory, Caspar René (1900). Textkritik des Neuen Testaments. 1. Leipzig. p. 22.

- Gardthausen, pp.124–125.

- Kirsopp Lake, pp.32-35

- Schumacher, p.47

- Skeat, pp.583–625

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration (4th ed.). New York – Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16.

Further reading

- Elliott, James Keith, The collected biblical writings of T.C. Skeat, Dating and Origin of Codex Vaticanus

- Gardthausen, Victor, Griechische paleographie, 2 vol., Leipzig, 1913

- Gregory, Caspar René, The Canon and Text of the New Testament (Edinburgh 1907)

- Lake, Kirsopp, The Sinaitic and Vatican manuscripts and the copies sent by Eusebius to Constantine, Harvard Theological Review, vol. XI (1918)

- McDonald & Sanders, The Canon Debate

- Price, I. M. (1923), The Ancestry of Our English Bible an Account of Manuscripts, Texts and Versions of the Bible, Sunday School Times Co, s. 146 f.

- Schumacher, Heinrich, A handbook of Scripture study (1922)

- Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose, A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, George Bell & Sons, London (1894)

- Skeat, Teodor Cressy, The Codex Sinaiticus, The Codex Vaticanus and Constantine, Journal of Theological Studies 50 (1999)

- Westcott & Hort, Introduction to the New Testament in the Original Greek (Harper & Brothers: New York, 1882)

External links

- Eusebii Pamphili de vita Constantini, libri IV, F. A. Heinichen, 1830

- The Bibles of Constantine at The Development of the Canon of the New Testament

- Saan Galin Ang Biblia, pp. 24–25