Film Booking Offices of America

Film Booking Offices of America (FBO), also known as FBO Pictures Corporation,[1] was an American film studio of the silent era, a producer and distributor of mostly low-budget films. It was founded in 1920 as Robertson–Cole (U.S.), the American division of a British import–export company formed by the English-born Harry F. Robertson.[2] Robertson-Cole bought the Hallmark Exchanges (formerly the Mutual Exchanges that became known as Exhibitors-Mutual Exchanges) from Frank G. Hall in 1920. Exhibitors-Mutual/Hallmark had distributed Robertson-Cole product, and acquiring the exchanges gave them the right to distribute their own films plus Hall's product, with the exception of Charlie Chaplin reissues which he had the rights to.[3]

FBO last logo from 1927 | |

| Type | Corporation |

|---|---|

| Industry | Motion pictures |

| Fate | Assets transferred to Radio-Keith-Orpheum Corp. |

| Predecessor | Robertson-Cole Corp. |

| Successor | RKO Pictures |

| Founded | c. 1919 (as Robertson-Cole Corp., U.S. division of Robertson-Cole [UK]) |

| Defunct | 1928/29 |

| Headquarters | New York City |

Robertson-Cole initiated movie production in the United States in 1920. That year, it incorporated Robertson-Cole Studios, Inc. and bought 460 acres in Pacific Palisades, California to establish a studio. The property, which became known as the "R.C. Ranch", enabled Robertson-Cole to centralize movie production, which previously had been scattered. The movie company had relied on equipment rentals to produce motion pictures.[4] Two years later, a corporate reorganization led to the company's new name, with FBO becoming the official name of the distributing operation and Robertson-Cole Pictures Corp. the name of the production operation.[5] In 1923, the studio contracted with Western actor Fred Thomson, who would soon emerge as one of Hollywood's most popular stars. Thomson was just one of the numerous screen cowboys with whom FBO became identified.

The studio, whose core market was America's small towns, also put out many romantic melodramas, non-Western action pictures, and comedic shorts. In 1926, financier Joseph P. Kennedy led a group that acquired the company. In June 1928, using RCA Photophone technology, FBO became the second Hollywood studio to release a feature-length "talkie." A few months later, when Kennedy and RCA chief David Sarnoff arranged the merger that created RKO, FBO was included in the new company.

Business history

Foundation and identity

The company that would become FBO began as the U.S.-based film subsidiary of the British importer, exporter, and film distributor Robertson-Cole. This organization was similar in structure to the French Pathé Exchange company, a subsidiary of the French Pathé Frères company. From its U.S. headquarters in New York City, R-C Pictures, as it was sometimes known, first entered the American film distribution market. In 1919, the company forged an alliance with Exhibitors Mutual Distributing, a corporate descendant of the Mutual Film studio.[6] The first of R-C's own feature productions to be released was The Wonder Man, directed by John G. Adolfi and starring Georges Carpentier, which debuted May 29, 1920.[7] With its move into production, Robertson-Cole established a 13.5-acre (5.5-hectare) studio in Los Angeles's fortuitously named Colegrove district, then adjacent to but soon to be subsumed by Hollywood.[8] In January 1921, Robertson-Cole absorbed Hallmark Pictures, which had acquired the Exhibitors Mutual interests the previous year.[9] The first official Robertson-Cole production shot at the new studio was a February 1921 release, The Mistress of Shenstone, directed by Henry King and starring beautiful Pauline Frederick, a former Paramount and Goldwyn star.[10] That year, the British owners of the studio entered into a working relationship with Joseph P. Kennedy, father of future U.S. president John F. Kennedy. Joseph Kennedy was then a broker at the New York banking firm of Hayden, Stone, as well as the owner of Maine–New Hampshire Theatres, a small chain of movie houses.[11] Though he failed to arrange the sale R-C's general partners were looking for, Kennedy's involvement with the studio was far from over.

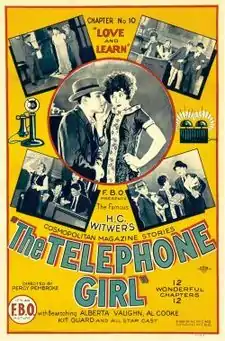

In 1922, Robertson-Cole underwent a major reorganization as the company's founders departed, though the corporation remained under majority British ownership. The flagship U.S. distribution business changed its name to Film Booking Offices of America, a banner under which R-C had released more than a dozen independent productions. The West Coast studio apparently continued to make films under the Robertson-Cole name for some time, but FBO ultimately became the primary identity of the business for production as well as distribution.[12] Between the 1922 reorganization and October 1923, one of the company's new American investors, Pat Powers, was effectively in command. Powers had previously led his own filmmaking company, part of the multiple mergers that created the large Universal studio in 1912. Powers apparently changed the name of Robertson-Cole/FBO to the Powers Studio for a brief period, though there is no record of the company ever having produced or released a film under that banner.[13] In 1923, the studio launched a series of boxing-themed shorts, Fighting Blood, starring George O'Hara. He would become an FBO mainstay, often paired with Alberta Vaughn, in such comedy series as The Pacemakers (1925). Most of O'Hara's and Vaughn's films for the studio were two-reelers—a measure of film length indicating a running time of about twenty minutes.

Now a fully independent businessman, Joseph Kennedy joined the FBO board of directors in 1923, as well. By this time, the studio was owned by Graham's of London, a banking firm, and Powers was succeeded by H.C.S. Thomson, a Graham's operative.[14] Before leaving the board the following year, Kennedy put together a major distribution and production deal between FBO and leading Western star Fred Thomson.[15] B. P. Fineman became the studio's production chief in 1924; Evelyn Brent, his wife, moved over from Fox to become FBO's top dramatic star.[16] In April 1925, FBO vice-president Joseph I. Schnitzer signed Thomson to a new contract paying him $10,000 a week (equivalent to approximately $145,787 in 2019 dollars[17]). Thomson was now the highest paid of all cowboy actors, surpassing even the renowned Tom Mix. The deal also gave Thomson his own independent production unit at the studio.[18]

As a distributor, FBO's roster of films was about half independent and foreign productions, half its own studio output. At the height of its activity (1923–28), it released an average of around 110 features and shorts a year, focusing on distribution to small-town exhibitors and independent theater chains (that is, those not owned by one of the major Hollywood studios).[19] As a production company, Film Booking Offices concentrated on low-budget movies, with an emphasis on Westerns, romantic melodramas, and comedy shorts. From its first productions in early 1920 through late 1928, when it was dissolved in a merger, the company produced approximately 400 films under the brand of either Robertson-Cole Pictures or FBO Pictures. Between 1924 and 1926, several higher-end productions were made under the rubric of Gothic Pictures. The studio's top-of-the-line movies, aimed at major exhibition venues beyond the reach of most FBO films, were sometimes marketed as FBO "Gold Bond" pictures.[20] Without the backing of large corporate interests, nor the security of its own theater chain, the company faced cash-flow difficulties during its earlier years. Short-term loans at high interest rates posed a significant financial drain.[21]

Kennedy takes command

While still at Hayden, Stone, Kennedy had boasted to a colleague, "Look at that bunch of pants pressers in Hollywood making themselves millionaires. I could take the whole business away from them."[22] In 1925, he set out to do so, forming his own group of investors led by wealthy Boston lawyer Guy Currier and including Filene's department store owner Louis Kirstein and Union Stockyards and Armour and Company owner Frederick H. Prince. In August 1925, Kennedy traveled to England with an offer to buy a controlling stake in Film Booking Offices for $1 million. The bid was initially rejected, but in February 1926, FBO's owners decided to take the money.[23] In short order, Kennedy moved his family from Massachusetts to New York City to focus on running his new business. He swiftly addressed the company's perennial cash-flow problems, arranging lines of credit and issuing stock in a business division he established, the Cinema Credit Corporation.[24] By March, he was traveling to Hollywood.[25] The president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, Will Hays, was delighted by the new face on the scene—in Hays's eyes, Kennedy signified both a desirable image for the industry and Wall Street's faith in its prospects. Hays heralded Kennedy as "exceedingly American" (historian Cari Beauchamp explains the connotation: "not Jewish," in contrast to most of the studio heads), while celebrating Kennedy's "background of lofty and conservative financial connections, an atmosphere of much home and family life and all those fireside virtues of which the public never hears in the current news from Hollywood."[26]

Fineman and Brent both departed FBO around the time of the purchase. Kennedy appointed Edwin King as the studio's production chief, but the new owner took a personal hand in guiding the company creatively as well as financially.[27] Kennedy soon brought stability to FBO, making it one of the most reliably profitable outfits in the minor leagues of the Hollywood studio system. Westerns remained the studio's backbone, along with various action pictures and romantic scenarios; as Kennedy put it, "Melodrama is our meat."[28] During this period, the average production cost of FBO features was around $50,000, and few were budgeted at anything more than $75,000.[29] By comparison, in 1927–28 the average cost at Fox was $190,000; at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, $275,000.[30] One major expense was taken on directly by Kennedy: with several studios competing for Fred Thomson, Kennedy signed him to a personal contract for $15,000 a week. This was the highest straight salary for any actor in the industry, matched only by Tom Mix's new arrangement with Fox.[31] Under the contract, Kennedy struck a deal in early 1927 with Paramount Pictures for the major studio to produce and distribute a series of four Thomson "super westerns." Kennedy participated in the films' financing (and profits) and the actor's company stayed on the FBO lot. Of the four Thomson features that reached theaters in 1927, three were FBO releases.[32]

Sound enters the picture

The advent of sound film would drastically alter the studio's course: Negotiations that began in late 1927 with the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) on a deal for sound conversion led to RCA purchasing a major interest in FBO in January 1928. Four months later, as part of a strategy conceived with RCA head David Sarnoff, Kennedy acquired control of Keith-Albee-Orpheum (KAO), a vaudeville exhibition chain with approximately one hundred theaters across the United States, and with the Pathé Exchange and Cecil B. DeMille's Producers Distributing Corporation under its control.[33]

On June 17, 1928, FBO's The Perfect Crime, directed by Bert Glennon and starring Clive Brook and Irene Rich, debuted.[34] It was the first feature-length "talkie" to appear from a studio other than Warner Bros. since the epochal premiere of Warners' The Jazz Singer eight months before. The Perfect Crime, which went into general release on August 4, had been shot silently. Using the RCA Photophone sound-on-film system, the dialogue was dubbed in afterward—a process then known as "synthetic sound."[35] On August 22, Kennedy signed a contract with RCA for live Photophone recording; more importantly, he also tendered the company an option to buy his governing share of FBO. Two months later, RCA had acquired controlling stock interests in both the studio and KAO.

On October 23, 1928, RCA announced it was merging Film Booking Offices and Keith-Albee-Orpheum to form the new motion picture business Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO), with Sarnoff as chairman.[36] Kennedy, who retained Pathé, was paid $150,000 for arranging the merger on top of the millions of dollars in profit he made from selling off his stock.[37] Joseph I. Schnitzer, ranking FBO vice-president, was elevated to president of the new company's production arm, replacing Kennedy.[38] William LeBaron, the last FBO production chief, retained his position after the merger, but the new studio, dedicated to full sound production, cut ties with most of FBO's roster of silent-screen performers. Movies that Film Booking Offices had either produced or arranged to distribute were released under the FBO banner through the end of 1929. The last official FBO production to reach American theaters was Pals of the Prairie, directed by Louis King and starring Buzz Barton and Frank Rice, released July 1, 1929.

Cinematic legacy

Headliners and celebrity casting

The vast majority of FBO/Robertson-Cole pictures, produced during either the silent era or the transitional period of the conversion to sound cinema, are considered to be lost films, with no copies now known to exist. Partly in consequence, many of FBO's star actors are barely remembered today.

Pauline Frederick was the major headliner of the early R-C days, and Evelyn Brent was FBO's most prized non-Western star.[16] Warner Baxter, Joe E. Brown, and young Frankie Darro were among the other prominent FBO players. Anna Q. Nilsson starred in two of the studio's larger productions, as did Olive Borden and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. FBO's leading star of action and mystery pictures was Richard Talmadge. He appeared in eighteen FBO releases, more than half of them produced by his own company. Maurice "Lefty" Flynn starred in over a dozen FBO action films, all directed by Harry Garson, who also ran his own production business.[39] From the studio's pre-Hollywood days in 1920 through 1928, Ralph Lewis starred in more than ten R-C and FBO pictures of various genres. Former model Reed Howes, renowned as an "Arrow Collar Man", made his acting debut with FBO after an extensive publicity campaign.[40]

In its earlier years, the studio did not hesitate to take advantage of scandal sheet–worthy events. After the death of celebrated Paramount actor Wallace Reid, brought on by morphine addiction, his widow, Dorothy Davenport, signed on as producer and star of a cinematic examination of the sins of substance abuse: Human Wreckage, released by FBO in June 1923, five months after Reid's death, featured Davenport (billed as Mrs. Wallace Reid) as the wife of a noble attorney turned dope fiend.[41]

When the biggest movie star in the world, Rudolph Valentino, split from his wife, Natacha Rambova, she was swiftly enlisted by the studio to costar with Clive Brook in the sensitively titled When Love Grows Cold (1926).[42] Under Kennedy's control, studio production shifted away from provocative fare in an attempt to brand the studio's films as suitable for the "average American" and the entire family: "We can't make pictures and label them 'For Children,' or 'For Women' or 'For Stout People' or 'For Thin Ones.' We must make pictures that have appeal to all."[43] Though Kennedy ended the scandal-sheet specials, FBO still found occasion for celebrity casting: One Minute to Play (1926), directed by Sam Wood, marks the film debut of football great "Red" Grange.[44]

Western stars

Central to the FBO identity were Westerns and the studio's major cowboy star, Fred Thomson. In both 1926 and 1927, he ranked number two in the Exhibitors' Herald survey of the "Top Stars of the Year," right behind Tom Mix.[45] With Thomson's personal contract with Kennedy due to expire in mid-1927,[46] Kennedy—sending that Thomson had reached the peak of his popularity and seeing a financial opportunity for FBO—arranged a four-picture deal with Paramount Pictures, one of the major Hollywood studios. The deal essentially ceded Thomson to the rival studio. For FBO's guarantee of $75,000 in financing per picture, Thomson would star in Paramount productions. In return, Paramount would return the $75,000 in financing plus an additional $100,000 to FBO and pay Thomson's $15,000 a week salary.[47]

In 1928, Kennedy replaced Thomson by signing Tom Mix, whose contract with William Fox's Fox Film Corporation had expired. Mix played hard-to-get, threatening to move to Argentina to make films or joining the circus, but eventually, he signed with FBO but eventually left for Universal due to salary disputes with the studio. He said of Kennedy that he was a "tight-assed, money-crazed son-of-a-bitch".[48]

FBO's second-biggest long-running Western star was Tom Tyler. According to a June 1927 report in Moving Picture World:

With Tom Tyler rapidly taking the place recently vacated by Fred Thomson, F.B.O.'s program of western pictures is taking a place second to none in the industry.... Tyler has made rapid strides during his two years with F.B.O. and with his horse 'Flash' and dog 'Beans' has become one of the leading favorites on the screen.[49]

In addition to these three big names there was also Harry Carey, still a major star when he made several films for the studio in 1922–23. The other cowboy stars of FBO included Bob Custer, Bob Steele, and teenager Buzz Barton.

Canine stars

One of the studio's most reliable Western headliners was a dog: Ranger.[50] The fabled Strongheart starred in FBO's White Fang (1925), and Rin Tin Tin had one of his earliest roles in My Dad (1922).[51]

Short subjects and animation

FBO's many shorts—the popular George O'Hara and Alberta Vaughn series, and scores of others—are largely forgotten. Of particular historical interest are two independently produced series of slapstick comedies with important performers: FBO put out several shorts in 1924–25 made by Joe Rock and starring Stan Laurel, before his famous partnership with Oliver Hardy. In 1926–27, the company distributed more than a dozen shorts by innovative comedian/animator Charles Bowers.[52]

In addition to the work of Charles Bowers, FBO was a distributor of other significant animated films. Between 1924 and 1926, FBO released the work of John Randolph Bray's cartoon studio, including the Dinky Doodle series created by Walter Lantz.[53] From 1925 to 1927, the studio put out approximately three dozen animated adaptations of George Herriman newspaper comics directed by William Nolan, featuring characters from Herriman's famed Krazy Kat strip. FBO picked up the Krazy Kat cartoons from the distribution team of Margaret Winkler and her husband, Charles Mintz. In 1926, FBO struck a deal with the Winkler–Mintz operation for another series, one that, like Bowers' shorts, involved both animation and a live performer: the Alice Comedies, of which FBO would put out over two dozen, were created by two young animators, Ub Iwerks and Walt Disney.[54]

Notable films and filmmakers

Kennedy had no illusions about his studio's place in the realm of cinematic art. A journalist once complimented him on FBO's recent output: "You have had some good pictures this year." Kennedy jocularly inquired, "What the hell were they?"[55] In her history of RKO, author Betty Lasky points to the pre-Kennedy Broken Laws (1924), directed by Roy William Neill and starring Dorothy Davenport (again billed as Mrs. Wallace Reid) as exemplifying the rare "unforgettable picture of the higher caliber" put out by FBO.[56]

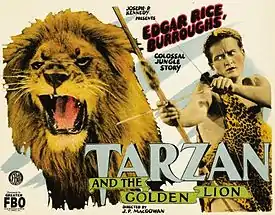

Among the studio's action movies, one standout production was a 1927 Tarzan picture. Author Edgar Rice Burroughs declared, "If you want to see the personification of Tarzan of the Apes as I visualize him, see the film Tarzan and the Golden Lion with Mr. James Pierce."[57] The Film Daily reviewer wrote that the movie "has a rather new order of thrills and atmosphere that might prove distinctly attractive."[57] The two-reeler West of Hot Dog (1924), according to historian Simon Louvish, contains "one of Stan [Laurel]'s finest gags," involving a level of cinematic technique that bears comparison to Buster Keaton's classic Sherlock Jr.[58]

Some of the studio's most impressive releases were foreign productions. In 1927, FBO picked up for U.S. distribution a celebrated Austrian biblical spectacular made three years earlier: Die Sklavenkönigin (The Slave Queen, aka Moon of Israel) had already won its director, Michael Kertész, a job with Warner Bros.[59] In Hollywood, he would change his name to Michael Curtiz. Una Nueva y gloriosa nación (1928), the most successful film in the history of Argentine silent cinema, was shot in Hollywood and distributed in the United States by FBO as The Charge of the Gauchos.[60]

One of the two cinematographers of Una Nueva y gloriosa nación was Nicholas Musuraca, who established his career at Film Booking Offices. With RKO, Musuraca would become one of Hollywood's most respected cinematographers.

Among FBO's other offscreen talent, the best known director to work regularly at the studio was Ralph Ince, younger brother of famous filmmaker Thomas H. Ince. Pulling double duty on occasion, Ralph Ince starred in four of the fourteen films he made for FBO. One production in which Ince served in both capacities was particularly well received: Chicago After Midnight (1928) was described by the New York Times as "[a]n unusually well-acted and adroitly directed underworld story."[62] After The Mistress of Shenstone, Henry King directed two more R-C films with Pauline Frederick, also in 1921: Salvage and The Sting of the Lash.[63] Tod Browning directed two Gothic Pictures specials in 1924 starring Evelyn Brent: The Dangerous Flirt and Silk Stocking Sal.[64]

From 1921 to 1924, William Seiter directed a half-dozen FBO releases, some produced directly for the studio, others independently. Between 1922 and 1926, Emory Johnson produced and directed eight films for FBO. Historian William K. Everson has pointed to Seiter and Johnson as two of the overlooked directorial talents of the silent era.[65]

Screenwriter Frances Marion, who would win two Oscars in the 1930s, penned ten of the FBO pictures starring her husband, Fred Thomson. Editor Pandro S. Berman, son of a major FBO stockholder, cut his first film for the studio at the age of twenty-two; he would go on to renown as an RKO producer and production chief. Famed RKO costume designer Walter Plunkett was also an FBO graduate.

Notes

- Many sources give FBO's full name incorrectly as "Film Booking Office of America"; the proper name is Film Booking Offices of America, as per the company's official logo. For the correct spelling. See Sherwood (1923), pp. 150, 156, 158, 159, etc.; Ellis and Thornborough (1923), p. 262.

- "Screen; Again the import tax". New York Times. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- "Robertson-Cole Buys" (PDF). Variety. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- "Inceville: Robertson-Cole Buys a Ranch; Purchases 460 Acres of Land in Pacific Palisades, Cal". Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- "Silent Studios Directory - R". Learn About Movie Posters. Archived from the original on 2013-11-11.

- Goodwin (1987) describes Robertson-Cole as an "American motion picture firm" (p. 341), which was functionally true after a certain point, but Jewell (1982) makes clear that the company was founded in Britain and that its American operations were run by Britishmen through 1922 (p. 8). As Goodwin and Jewell concur, majority ownership of FBO remained in British hands until 1926.

- For a description of the film, see the anonymous New York Times review, May 30, 1920 (available online).

- The studio's address was and remains 780 Gower Street. See Finler (1988), p. 12, for a map showing the FBO studio (later owned by RKO, Desilu, and now CBS Paramount Television) in relation to the other main Hollywood production facilities. Finler misidentifies Melrose Ave., which runs east-west along the south of the studio, as "Beverly Boulevard." Gower St. runs north-south along the studio's western side.

- Lyons (1974), p. 90 n. 123.

- For descriptions of the film, see the reviews in Moving Picture World (March 5, 1921) and Variety (March 18, 1921).

- Goodwin (1987), p. 342.

- See, e.g., "F.B.O. Announces" (1925) for evidence that the studio was primarily identified as FBO by no later than summer 1925. Though Robertson-Cole apparently remained the primary production brand for a period after the 1922 reorganization, Lasky (1989, p. 13) and Jewell (1982, p. 8) both indicate that the entire film business was incorporated that year as Film Booking Offices of America Inc. Beauchamp (1998) refers to Kennedy's 1926 takeover of "R-C Pictures Corporation and Film Booking Office of America" (p. 180). These various references suggest that, from 1922 forward, R-C (or Robertson-Cole) Pictures Corp. was the legal name of FBO (or Film Booking Offices of America) Inc.'s studio subsidiary. Logos from 1927 and 1928 (the latter pictured in the article) reading "FBO Pictures Corp." suggest that the corporate name of the studio operation was changed after the Kennedy purchase.

- Lasky (1989), p. 13; Jewell (1982), p. 8.

- Lasky (1989), p. 13.

- Beauchamp (1998), pp. 157–58. See also John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum/Joseph P. Kennedy (#136) Archived 2006-09-04 at the Wayback Machine descriptive summary of material from the inventory of the late president's papers; refer to "Biographical Note." Retrieved May 6, 2007.

- Jewell (1982), p. 8.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Beauchamp (1998), p. 168.

- Beauchamp (1998), p. 157.

- "F.B.O. Announces" (1925).

- Lasky (1989), pp. 12–13, 14–15; Beauchamp (1998), p. 180.

- Quoted in Lasky (1989), p. 12.

- Goodwin (1987), pp. 342, 343; Beauchamp (1998), p. 180; Lasky (1989), p. 13. Crafton (1997) writes that the business Joseph Kennedy purchased in February 1926 was "a small Hollywood studio, Robertson-Cole, and its New York distributor, Film Booking Office (FBO)" (p. 136). This is potentially misleading, even aside from the misspelling of FBO's name; the available evidence demonstrates that Film Booking Offices was already the studio operation's primary identity, even though it might still have been registered as R-C Pictures Corporation or some variation thereof. Crafton's nomenclature is belied by his own earlier listing of the significant U.S. film production companies of the mid-1920s, among which he names "Film Booking Office (FBO)," not Robertson–Cole (p. 68).

- Lasky (1989), pp. 14–15; Goodwin (1987), p. 344.

- Goodwin (1987), pp. 345, 346.

- Quoted in Beauchamp (1998), p. 180. See also p. 197; Lasky (1989), p. 14. For Hays and Kennedy's earlier association, see Goodwin (1987), p. 341.

- Lasky (1989), p. 15. Crafton (1997) misleadingly implies that Kennedy immediately installed William LeBaron as production chief after his takeover of FBO (p. 136). In fact, as Jewell (1982) describes, King was the first head of production named by Kennedy, with LeBaron assuming the job in 1927 (p. 9).

- Quoted in Goodwin (1987), p. 348.

- Goodwin (1987), p. 348; Jewell (1982), p. 9.

- Finler (1988), p. 36.

- Beauchamp (1998), pp. 210, 211; Koszarski (1990), p. 116.

- Beauchamp (1998), pp. 211, 227.

- "Cinemerger" (1927); Lasky (1989), pp. 24–26. Note that the statement in Jewell (1982) referring to "the 700 K-A-O Theatres in the US and Canada" (p. 10) is wildly inaccurate and may well be a typo. Lasky (1989) says "several hundred theaters" (p. 25), Beauchamp (1998), citing Lasky, says "three hundred theaters" (quote: p. 228, cite: p. 414 n. 41)—figures belied by Time magazine's contemporary data (see "Cinemerger").

- For a description of the film, see the anonymous New York Times review, August 6, 1928 (available online). According to Crafton (1997), The Perfect Crime "premiered June 17, 1928 and opened at the Rivoli on August 4" (p. 140).

- Crafton (1997), pp. 140, 304.

- While all other latter-day published sources give October as the date of the merger, Crafton (1997) states, "The new holding company, Radio-Keith-Orpheum, was formed on 21 November 1928" (p. 142).

- Lasky (1989), pp. 33–34.

- Jewell (1982), p. 10.

- For more on Flynn, see Christgau (1999), pp. 55–59.

- Corneau (1969), p. 85.

- Schaefer (1999), p. 224.

- Goodwin (1987), p. 341.

- Quoted in Goodwin (1987), p. 347.

- Hall (1926). See also Heritage Vintage (2004b), p. 121.

- Beauchamp (1998), p. 224.

- Lasky (1989), p. 17; Beauchamp (1998), p. 227.

- Beauchamp, Cari (2010). Joseph P. Kennedy Presents: His Hollywood Years. New York: Knopf. pp. 164–65. ISBN 978-1400040001.

- Quirk, Lawrence J. (1996). The Kennedys in Hollywood. Taylor Publications. p. 303. ISBN 978-0878339341.

- Moving Picture World, June 11, 1927.

- The suggestion by Goodwin (1987) that, during Kennedy's tenure, FBO made "a dozen dog pictures...each year" (p. 348) is exaggerated. Ranger, the studio's only canine headliner of the Kennedy era, starred in sixteen pictures over the course of three years. From before the Kennedy era through 1928, Beans had featured roles in a number of Tom Tyler/Frankie Darro Westerns. For examples of how such films were marketed, see Heritage Vintage (2004a), p. 79, and Heritage Vintage (2005), p. 35. In the latter, note that the text accompanying the reproduced poster of Tom and His Pals (1926) incorrectly identifies the film as a Paramount picture; despite what the text implies, this was not the first film teaming Tyler and Darro.

- For a description of the former, see Sandburg (1925), pp. 270–271. For a description of the latter, see Janiss Garza, "My Dad" Allmovie review; part of New York Times website. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- For more on Bowers' work with FBO, see Crafton (1993), p. 362 n. 39.

- Crafton (1993), pp. 186, 187; Langer (1995), pp. 105, 259 n. 40. For posters of two Bray/Lantz cartoons distributed by FBO, see Heritage Vintage (2004b), p. 51.

- Crafton (1993), p. 285; Langer (1995), p. 259 n. 39.

- Quoted in Lasky (1989), p. 14.

- Lasky (1989), p. 14.

- Quoted in Fenton (2002), p. 107.

- Louvish (2001), pp. 171–72.

- Kemp (1987), p. 173.

- Finkielman (2004), p. 84.

- For a description of the film, see Buehrer (1993), pp. 43–44.

- Hall (1928).

- For a description of the former, see the review in Variety, June 17, 1921. For descriptions of the latter, see the reviews in Harrison's Reports (October 1, 1921) and Variety (October 21, 1921).

- For a brief description of the former, see Sullivan (1986), p. 60. For a description of the latter, see Langman (1998), p. 88.

- Everson (1998), p. 142.

Sources

- Beauchamp, Cari (1998). Without Lying Down: Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press). ISBN 0-520-21492-7

- Buehrer, Beverley Bare (1993). Boris Karloff: A Bio-Bibliography (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press). ISBN 0-313-27715-X

- Christgau, John (1999). The Origins of the Jump Shot: Eight Men Who Shook the World of Basketball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press). ISBN 0-8032-6394-5

- "Cinemerger" [anon.] (1927). Time, May 2 (available online).

- Corneau, Ernest N. (1969). The Hall of Fame of Western Film Stars (Hanover, Mass.: Christopher Publishing House). ISBN 0-8158-0124-6

- Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Film, 1898–1928 (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press). ISBN 0-226-11667-0

- Crafton, Donald (1997). The Talkies: American Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1926–1931 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons). ISBN 0-684-19585-2

- Ellis, Don Carlos, and Laura Thornborough (1923). Motion Pictures in Education: A Practical Handbook for Users of Visual Aids (New York: Thomas V. Crowell).

- Everson, William K. (1998). American Silent Film (New York: Da Capo). ISBN 0-306-80876-5

- "F.B.O. Announces Tom Tyler as 'Surprise' Western Star" [anon.] (1925). Moving Picture World, August 8.

- Fenton, James W. (2002). Edgar Rice Burroughs and Tarzan: A Biography of the Author and His Creation (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland). ISBN 0-7864-1393-X

- Finkielman, Jorge (2004). The Film Industry in Argentina: An Illustrated Cultural History (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland). ISBN 0-7864-1628-9

- Finler, Joel W. (1988). The Hollywood Story (New York: Crown). ISBN 0-517-56576-5

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (1987). The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys: An American Saga (New York: Simon & Schuster). ISBN 0-671-23108-1

- Hall, Mordaunt (1926). "'Red' Grange's First Film," The New York Times, September 6 (available online).

- Hall, Mordaunt (1928). "An Irish Mother. Bootleggers and Night Clubs," The New York Times, March 6 (available online).

- Heritage Vintage Movie Poster Signature Auction #603 (Dallas: Heritage Vintage Movie Posters, 2004a). ISBN 1-932899-15-4

- Heritage Vintage Movie Poster Signature Auction #607 (Dallas: Heritage Vintage Movie Posters, 2004b). ISBN 1-932899-35-9

- Heritage Vintage Movie Poster Signature Auction #624 (Dallas: Heritage Vintage Movie Posters, 2005). ISBN 1-59967-004-6

- Jewell, Richard B., with Vernon Harbin (1982). The RKO Story (New York: Arlington House/Crown). ISBN 0-517-54656-6

- Kemp, Philip (1987). "Curtiz, Michael," in World Film Directors, Volume 1: 1890–1945, ed. John Wakeman (New York: H. W. Wilson), 172–181. ISBN 0-8242-0757-2

- Koszarski, Richard (1990). An Evening's Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928 (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press). ISBN 0-520-08535-3

- Langer, Mark (1995). "John Randolph Bray: Animation Pioneer," in American Silent Film: Discovering Marginalized Voices, ed. Gregg Bachman and Thomas J. Slater (Carbondale: Southern Illinois Univ. Press, 2002), pp. 94–114. ISBN 0-8093-2402-4

- Langman, Larry (1998). American Film Cycles: The Silent Era (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press). ISBN 0-313-30657-5

- Lasky, Betty (1989). RKO: The Biggest Little Major of Them All (Santa Monica, Calif.: Roundtable). ISBN 0-915677-41-5

- Louvish, Simon (2001). Stan and Ollie: The Roots of Comedy: The Double Life of Laurel and Hardy (New York: St. Martin's). ISBN 0-312-26651-0

- Lyons, Timothy James (1974 [1972]). The Silent Partner: The History of the American Film Manufacturing Company, 1910–1921 (New York: Arno Press). ISBN 0-405-04872-6

- Sandburg, Carl (1925). "White Fang," in The Movies Are: Carl Sandburg's Film Reviews and Essays, 1920–1928, ed. Arnie Bernstein (Chicago: Lake Claremont Press, 2000), pp. 270–71. ISBN 1-893121-05-4

- Schaefer, Eric (1999). "Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!": A History of Exploitation Films, 1919–1959 (Durham and London: Duke University Press). ISBN 0-8223-2374-5

- Sherwood, Robert Emmet (1923). The Best Moving Pictures of 1922–23 (Boston: Small, Maynard).

- Sullivan, Jack, ed. (1986). The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and The Supernatural (New York: Viking). ISBN 0-670-80902-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Film Booking Offices of America films. |

- "The Silent Films of FBO Pictures".

<- THIS LINK IS NO LONGER VALID

comprehensive listing of silent features produced by FBO/Robertson–Cole and released between 1925 and 1929—see also The Early Sound Films of Radio Pictures for FBO sound productions released in 1928 (the list does not clearly indicate the several FBO sound productions released in 1929); both part of Vitaphone Video Early Talkies website