Finn Juhl

Finn Juhl (30 January 1912 – 17 May 1989) was a Danish architect, interior and industrial designer, most known for his furniture design. He was one of the leading figures in the creation of Danish design in the 1940s and he was the designer who introduced Danish modern to America.

Finn Juhl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 30 January 1912 |

| Died | 17 May 1989 (aged 77) Ordrup, Denmark |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | 1978 Honorary Royal Designer for Industry, London |

| Projects | Pelican chair (1940) Westermann's Fireside chair (1946) Egyptian chair (1949) Chieftain chair (1949) Japan chair (1953) Bwana chair (1962) |

Biography

Early life and education

Finn Juhl was born on 30 January 1912 to an authoritarian father who was a textile wholesaler representing several English, Scottish and Swiss textile manufacturers in Denmark, and a mother who died shortly after he was born. From an early age he wanted to become an art historian, already as a teenager spending much time at the Statens Museum for Kunst and in spite of his young age receiving permission to borrow books at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, but his father convinced him instead to pursue a career in architecture.[1] He was admitted to the Architecture School at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts where from 1930 to 1934 he studied under Kay Fisker, a leading architect of his day and noted lecturer.

Early career

After graduating, Juhl worked for ten years at Vilhelm Lauritzen's architectural firm, where he had also apprenticed as a student. In close collaboration with Viggo Boesen, Juhl was responsible for much of the interior design of the national broadcaster Danmarks Radio's Radiohuset, one of the firm's most high-profile assignments during those years.[2]

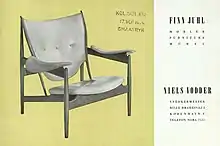

Juhl made his debut in 1937 when he commenced a collaboration with cabinetmaker Niels Vodder which would continue until 1959 and exhibited at the eleventh Copenhagen Cabinetmakers' Guild Exhibition. Therefore, his early chairs were originally produced in small numbers, eighty at most, because the Guild shows emphasized the work of the artisan over the burgeoning industry of mass production. However, they were almost all reissued later in his career.[3]

He married Inge-Marie Skaarups on 15 July 1937 but they later divorced.

The Guild Exhibitions were an important venue for the young designers who sought to renew Danish design, turning their backs on the traditional historicist styles, heavy and with ornaments and plush, instead creating modern furniture which fitted the new trends in architecture. The projects was highly controversial and Juhl's first work met much criticism. His Pelican chair, designed in 1939 and first produced in 1940, was described as a "tired walrus" and "aesthetics in the worst possible sense of the word".[4] In spite of the initial criticism, Juhl's work began to influence the style of homes abroad throughout the 1940s. In Denmark, however, his popularity did not reach that of his peers, Børge Mogensen and Hans Wegner, who were less radical in their designs and relied more on Kaare Klint, leader of the furniture school at the Academy and the Nestor of modern Danish furniture design.[4]

In 1942 Juhl designed a house for himself, today known as Finn Juhl's House, and had it built with money inherited from his father. Over the years, it was increasingly furnished with creations of his own design.

In 1945 he left Vilhelm Lauritzen Architects and set up his own design practice, in Nyhavn in Copenhagen, specializing in interior and furniture design. However, his work in furniture design began earlier than that. He also became a teacher at the Danmarks Designskole in 1945 and would continue to teach there until 1955.

International success

In 1948 Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., leader of the Department for Industrial Design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, toured Scandinavia. He intentionally did not visit only the big Scandinavian exhibitions, but being impressed by Juhl's work he presented it in a large article in the Interiors magazine. In 1951 he participated in the Good Design exhibition in Chicago. In connection with the show he was quoted in Interiors for stating that "One cannot create happiness with beautiful objects, but one can spoil quite a lot of happiness with bad ones". The work he did for them, 24 pieces including chairs, tables, storage units, sideboards and desks, represented his first successful marriage of modern mass production to his traditionally high craft standards.

In 1950, Baker Furniture Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan approached Juhl about producing his designs in their America factory. Initially skeptical of American craftsmanship, Juhl was assured after visiting Grand Rapids and agreed to the arrangement. Baker Furniture marketed Juhl's furniture under the 'Baker Modern' line.[5]

In 1951–52, he designed the Trusteeship Council Chamber in the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City. The Government of Denmark contributed approximately $20,000 towards its construction.[6]

At the Milan Triennial in the 1950s, he won a total of five gold medals, further adding to his international reputation. During this decade he continued to design more specifically for the mass market than had been the case in the 1940s.

From 1961 he lived in a common-law marriage with Hanne Wilhelm Hansen,[7] a member of the family behind the Edition Wilhelm Hansen music-publishing house.

In his career, Juhl also designed refrigerators for General Electric, glassware, ceramics, and was the interior designer for the United Nations Trusteeship Council Chamber in New York City.

In 1965 he was a visiting professor at the Institute of Design in Chicago.[7]

Death and legacy

In the 1960s and '70s he experienced a declining interest in his designs but in the late '90s, interest resurged.

Juhl died on 17 May 1989 and was buried in Copenhagen's Assistens Cemetery.

In 2000, Juhl's partner Hanne Wilhelm Hansen passed the rights to his designs to the company Onecollection. In 2010 one of his sofas, the 57 Sofa, relaunched by Onecollection, won a Wallpaper Design Award in the Best reissue/sofa design category.[8] Onecollection has changed its brand name to 'House of Finn Juhl' and the company has a collection of more than 40 relaunched pieces of Juhl's designs.

Hanne Wilhelm Hansen established the Finn Juhl Prize in 2003 to honor her partner's legacy. The prize is annually awarded to recipients who have made significant contributions in the field of furniture design.[9] After Hansen's death in May 2003, their home, which she had left unchanged after his death, was made into a historic house museum, operated as part of the Ordrupgaard Art Museum whose premises it adjoins.[10]

Style

.JPG.webp)

Juhl gave a soft edge to the lines of wooden modernist chairs, favouring organic shapes which often took the wood to the limits of what was possible. He generally used teak and other dark woods, unlike many of the other proponents of the Danish Modern movement who often used oak in their designs.[4]

He was influenced by the abstract sculptor Jean Arp, an influence which is seen already in his early Pelican chair but it remained a motif throughout his career. Also influenced by tribal art, Juhl exhibited the Chieftain chair with photos of weapons from anthropological studies.

One of his hallmarks was the floating back and seat which is seen in most of his chair designs, usually upholstered, in contrast to the hard wood of the bearing elements. The full back and seat, seeming to hover on their supports, start to emerge in the chairs from 1945 and 1948.

Selected works

.JPG.webp)

Furniture

- Pelican chair (1940)

- FJ41 aka Poet sofa (1941)

- NV44 chair (1944)

- NV45 chair (1945)

- FJ46 chair (1946)

- BO64 chair (1946)

- Westermann's Fireside chair aka BO59 (1946)

- FJ48 chair (1948)

- Egyptian chair (1949)

- Chieftain chair aka FJ49A (1949)

- Judas table (1946)

- Baker sofa (1951)

- BO98 chair (1952)

- Japan chair aka FD137 (1953)

- FJ53 chair (1953)

- BO101 chair (1953)

- FJ55 chair (1955)

- FD136 chair (1958)

- BO62 chair (1962)

- Bwana chair aka FD152 (1962)

Interior designs

His work also included numerous assignments within the field of interior design. Shortly after opening his own office, he received several commissions to do interior design at some of the premier addresses in Copenhagen, Bing & Grøndahl's shop on Amagertorv (1946), now housing Royal Copenhagen, and Svend Schaumann's florist's shop on Kongens Nytorv (1948). He also collaborated regularly with companies such as Georg Jensen and Scandinavian Airlines, his work for the latter including both ticket offices and interiors of planes. He also had many assignments as an exhibition designer.

- Bing & Grøndahl shop, Amagertorv, Copenhagen (1946)

- Svend Schaumann's florist's shop, Kongens Nytorv (1948)

- Trusteeship Council Chamber, U.N. Headquarters, New York (1951–52)

- Georg Jensen store, Fifth Avenue, New York (1952)

- Designed a room with his own furniture, etc. at the Nordenfjeldske Museum of Applied Art, Trondheim (1952)

- Georg Jensen silversmithy, 50th anniversary exhibition, Museum of Decorative Art, Copenhagen, 1954.

- Fifty Years of Danish Silver exhibition, London, [1954]; in Washington, Louisville and Dallas (1955); St. Louis (1957)

- Denmark's stand, Milan Triennial X, Italy (1954)

- Director's office for France & Daverkosen, Ørholm, (1955)

- Model apartment, H55 exhibition. Helsingborg, Sweden, (1955)

- 30 SAS ticket offices in Europe and Asia (1956–61)

- Georg Jensen shop, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (1956)

- Interior design of DC-8 planes for SAS

- Georg Jensen shop, New Bond Street, London (1957)

- Denmark's stand, Milan Triennial XI (1957)

- Furnished the ambassador's residence, Embassy of Denmark in Washington, D.C. (1960)

- Arts of Denmark, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1960)

- The Arts of Denmark exhibition moved to museums in Washington D. C., Chicago, and Los Angeles, 1960-61.

- Bing & Grøndahl shop expansion, Amagertorv, Copenhagen (1963)

- Wilhelm Hansen Musikforlag shop, Gothersgade, Copenhagen (1966)

Buildings

- Finn Juhl's House, Klampenborg, Denmark

- Mrs Anthon Petersen's summer house in Asserbo, Halsnæs Municipality, Denmark, 1950.

- Single-family house for M. Aubertin, Nakskov, Denmark, 1952

- Georg Jensen shop, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (1956)

- Summer house for Anders Hostrup-Pedersen (managing director of Georg Jensen), Rågeleje, Denmark (1962)

Awards and distinctions

- 1943 C. F. Hansen prize for young architects

- 1947 Eckersberg Medal, Denmark

- 1954 Honorary Diploma, Milan Triennial X, Italy

- 1957 three gold medals at the Milan Triennial XI

- 1960 Kaufmann International Design Award

- 1964 A.I.D. prize for design, Chicago

- 1978 Honorary Royal Designer for Industry, London

- Knight of the Order of Dannebrog, Copenhagen

- Best reisue/sofa design, 2010 Wallpaper Design Award[8]

Bibliography

- Hansen, Per H. (2014). Finn Juhl and His House. Hatje Cantz Verlag. ISBN 978-3775737975.

- Hiort, Esbjørn (1990). Finn Juhl: Furniture, Architecture, Applied Art. Danish Architectural Press. ISBN 87-7407-094-0.

- Oda, Noritsugu (2012). Finn Juhl. Heibonsha. ISBN 978-4582634648.

See also

References

- "History". onecollection. Archived from the original on 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- "Finn Juhl". Danish Furniture Design. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- "Contemporary Design profile: Finn Juhl". Finn Juhl estate. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- "Fremsynet enegænger sørgede for danske stole i USA". Politiken. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- Hollingsworth, Andrew (September 2009). Danish Modern. Gibbs Smith. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4236-1359-6.

- Photo, U. N. (1953-06-01). "The Trusteeship Council Chamber". United Nations Photo. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "CV". Onecollection. Archived from the original on 2010-02-02. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- "Design Awards 2010: the winners". Wallpaper. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- "Finn Juhl Prisen". Wilhelm Hansen Fonden (in Danish). Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- "Besøg den gode smags bolig". Politiken. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Finn Juhl. |