Flatness problem

The flatness problem (also known as the oldness problem) is a cosmological fine-tuning problem within the Big Bang model of the universe. Such problems arise from the observation that some of the initial conditions of the universe appear to be fine-tuned to very 'special' values, and that small deviations from these values would have extreme effects on the appearance of the universe at the current time.

In the case of the flatness problem, the parameter which appears fine-tuned is the density of matter and energy in the universe. This value affects the curvature of space-time, with a very specific critical value being required for a flat universe. The current density of the universe is observed to be very close to this critical value. Since any departure of the total density from the critical value would increase rapidly over cosmic time,[1] the early universe must have had a density even closer to the critical density, departing from it by one part in 1062 or less. This leads cosmologists to question how the initial density came to be so closely fine-tuned to this 'special' value.

The problem was first mentioned by Robert Dicke in 1969.[2]:62,[3]:61 The most commonly accepted solution among cosmologists is cosmic inflation, the idea that the universe went through a brief period of extremely rapid expansion in the first fraction of a second after the Big Bang; along with the monopole problem and the horizon problem, the flatness problem is one of the three primary motivations for inflationary theory.[4]

Energy density and the Friedmann equation

According to Einstein's field equations of general relativity, the structure of spacetime is affected by the presence of matter and energy. On small scales space appears flat – as does the surface of the Earth if one looks at a small area. On large scales however, space is bent by the gravitational effect of matter. Since relativity indicates that matter and energy are equivalent, this effect is also produced by the presence of energy (such as light and other electromagnetic radiation) in addition to matter. The amount of bending (or curvature) of the universe depends on the density of matter/energy present.

This relationship can be expressed by the first Friedmann equation. In a universe without a cosmological constant, this is:

Here is the Hubble parameter, a measure of the rate at which the universe is expanding. is the total density of mass and energy in the universe, is the scale factor (essentially the 'size' of the universe), and is the curvature parameter — that is, a measure of how curved spacetime is. A positive, zero or negative value of corresponds to a respectively closed, flat or open universe. The constants and are Newton's gravitational constant and the speed of light, respectively.

Cosmologists often simplify this equation by defining a critical density, . For a given value of , this is defined as the density required for a flat universe, i.e. . Thus the above equation implies

- .

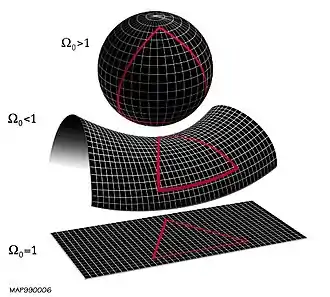

Since the constant is known and the expansion rate can be measured by observing the speed at which distant galaxies are receding from us, can be determined. Its value is currently around 10−26 kg m−3. The ratio of the actual density to this critical value is called Ω, and its difference from 1 determines the geometry of the universe: Ω > 1 corresponds to a greater than critical density, , and hence a closed universe. Ω < 1 gives a low density open universe, and Ω equal to exactly 1 gives a flat universe.

The Friedmann equation,

can be re-arranged into

which after factoring , and using , leads to

The right hand side of the last expression above contains constants only and therefore the left hand side must remain constant throughout the evolution of the universe.

As the universe expands the scale factor increases, but the density decreases as matter (or energy) becomes spread out. For the standard model of the universe which contains mainly matter and radiation for most of its history, decreases more quickly than increases, and so the factor will decrease. Since the time of the Planck era, shortly after the Big Bang, this term has decreased by a factor of around [5] and so must have increased by a similar amount to retain the constant value of their product.

Current value of Ω

Measurement

The value of Ω at the present time is denoted Ω0. This value can be deduced by measuring the curvature of spacetime (since Ω = 1, or , is defined as the density for which the curvature k = 0). The curvature can be inferred from a number of observations.

One such observation is that of anisotropies (that is, variations with direction - see below) in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation. The CMB is electromagnetic radiation which fills the universe, left over from an early stage in its history when it was filled with photons and a hot, dense plasma. This plasma cooled as the universe expanded, and when it cooled enough to form stable atoms it no longer absorbed the photons. The photons present at that stage have been propagating ever since, growing fainter and less energetic as they spread through the ever-expanding universe.

The temperature of this radiation is almost the same at all points on the sky, but there is a slight variation (around one part in 100,000) between the temperature received from different directions. The angular scale of these fluctuations - the typical angle between a hot patch and a cold patch on the sky[nb 1] - depends on the curvature of the universe which in turn depends on its density as described above. Thus, measurements of this angular scale allow an estimation of Ω0.[6][nb 2]

Another probe of Ω0 is the frequency of Type-Ia supernovae at different distances from Earth.[7][8] These supernovae, the explosions of degenerate white dwarf stars, are a type of standard candle; this means that the processes governing their intrinsic brightness are well understood so that a measure of apparent brightness when seen from Earth can be used to derive accurate distance measures for them (the apparent brightness decreasing in proportion to the square of the distance - see luminosity distance). Comparing this distance to the redshift of the supernovae gives a measure of the rate at which the universe has been expanding at different points in history. Since the expansion rate evolves differently over time in cosmologies with different total densities, Ω0 can be inferred from the supernovae data.

Data from the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (measuring CMB anisotropies) combined with that from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and observations of type-Ia supernovae constrain Ω0 to be 1 within 1%.[9] In other words, the term |Ω − 1| is currently less than 0.01, and therefore must have been less than 10−62 at the Planck era.

Implication

This tiny value is the crux of the flatness problem. If the initial density of the universe could take any value, it would seem extremely surprising to find it so 'finely tuned' to the critical value . Indeed, a very small departure of Ω from 1 in the early universe would have been magnified during billions of years of expansion to create a current density very far from critical. In the case of an overdensity () this would lead to a universe so dense it would cease expanding and collapse into a Big Crunch (an opposite to the Big Bang in which all matter and energy falls back into an extremely dense state) in a few years or less; in the case of an underdensity () it would expand so quickly and become so sparse it would soon seem essentially empty, and gravity would not be strong enough by comparison to cause matter to collapse and form galaxies. In either case the universe would contain no complex structures such as galaxies, stars, planets and any form of life.[10]

This problem with the Big Bang model was first pointed out by Robert Dicke in 1969,[11] and it motivated a search for some reason the density should take such a specific value.

Solutions to the problem

Some cosmologists agreed with Dicke that the flatness problem was a serious one, in need of a fundamental reason for the closeness of the density to criticality. But there was also a school of thought which denied that there was a problem to solve, arguing instead that since the universe must have some density it may as well have one close to as far from it, and that speculating on a reason for any particular value was "beyond the domain of science".[11] Enough cosmologists saw the problem as a real one, however, for various solutions to be proposed.

Anthropic principle

One solution to the problem is to invoke the anthropic principle, which states that humans should take into account the conditions necessary for them to exist when speculating about causes of the universe's properties. If two types of universe seem equally likely but only one is suitable for the evolution of intelligent life, the anthropic principle suggests that finding ourselves in that universe is no surprise: if the other universe had existed instead, there would be no observers to notice the fact.

The principle can be applied to solve the flatness problem in two somewhat different ways. The first (an application of the 'strong anthropic principle') was suggested by C. B. Collins and Stephen Hawking,[12] who in 1973 considered the existence of an infinite number of universes such that every possible combination of initial properties was held by some universe. In such a situation, they argued, only those universes with exactly the correct density for forming galaxies and stars would give rise to intelligent observers such as humans: therefore, the fact that we observe Ω to be so close to 1 would be "simply a reflection of our own existence."[12]

An alternative approach, which makes use of the 'weak anthropic principle', is to suppose that the universe is infinite in size, but with the density varying in different places (i.e. an inhomogeneous universe). Thus some regions will be over-dense (Ω > 1) and some under-dense (Ω < 1). These regions may be extremely far apart - perhaps so far that light has not had time to travel from one to another during the age of the universe (that is, they lie outside one another's cosmological horizons). Therefore, each region would behave essentially as a separate universe: if we happened to live in a large patch of almost-critical density we would have no way of knowing of the existence of far-off under- or over-dense patches since no light or other signal has reached us from them. An appeal to the anthropic principle can then be made, arguing that intelligent life would only arise in those patches with Ω very close to 1, and that therefore our living in such a patch is unsurprising.[13]

This latter argument makes use of a version of the anthropic principle which is 'weaker' in the sense that it requires no speculation on multiple universes, or on the probabilities of various different universes existing instead of the current one. It requires only a single universe which is infinite - or merely large enough that many disconnected patches can form - and that the density varies in different regions (which is certainly the case on smaller scales, giving rise to galactic clusters and voids).

However, the anthropic principle has been criticised by many scientists.[14] For example, in 1979 Bernard Carr and Martin Rees argued that the principle “is entirely post hoc: it has not yet been used to predict any feature of the Universe.”[14][15] Others have taken objection to its philosophical basis, with Ernan McMullin writing in 1994 that "the weak Anthropic principle is trivial ... and the strong Anthropic principle is indefensible." Since many physicists and philosophers of science do not consider the principle to be compatible with the scientific method,[14] another explanation for the flatness problem was needed.

Inflation

The standard solution to the flatness problem invokes cosmic inflation, a process whereby the universe expands exponentially quickly (i.e. grows as with time , for some constant ) during a short period in its early history. The theory of inflation was first proposed in 1979, and published in 1981, by Alan Guth.[16][17] His two main motivations for doing so were the flatness problem and the horizon problem, another fine-tuning problem of physical cosmology.

The proposed cause of inflation is a field which permeates space and drives the expansion. The field contains a certain energy density, but unlike the density of the matter or radiation present in the late universe, which decrease over time, the density of the inflationary field remains roughly constant as space expands. Therefore, the term increases extremely rapidly as the scale factor grows exponentially. Recalling the Friedmann Equation

- ,

and the fact that the right-hand side of this expression is constant, the term must therefore decrease with time.

Thus if initially takes any arbitrary value, a period of inflation can force it down towards 0 and leave it extremely small - around as required above, for example. Subsequent evolution of the universe will cause the value to grow, bringing it to the currently observed value of around 0.01. Thus the sensitive dependence on the initial value of Ω has been removed: a large and therefore 'unsurprising' starting value need not become amplified and lead to a very curved universe with no opportunity to form galaxies and other structures.

This success in solving the flatness problem is considered one of the major motivations for inflationary theory.[4][18]

Post inflation

Although inflationary theory is regarded as having had much success, and the evidence for it is compelling, it is not universally accepted: cosmologists recognize that there are still gaps in the theory and are open to the possibility that future observations will disprove it.[19][20] In particular, in the absence of any firm evidence for what the field driving inflation should be, many different versions of the theory have been proposed.[21] Many of these contain parameters or initial conditions which themselves require fine-tuning[21] in much the way that the early density does without inflation.

For these reasons work is still being done on alternative solutions to the flatness problem. These have included non-standard interpretations of the effect of dark energy[22] and gravity,[23] particle production in an oscillating universe,[24] and use of a Bayesian statistical approach to argue that the problem is non-existent. The latter argument, suggested for example by Evrard and Coles, maintains that the idea that Ω being close to 1 is 'unlikely' is based on assumptions about the likely distribution of the parameter which are not necessarily justified.[25] Despite this ongoing work, inflation remains by far the dominant explanation for the flatness problem.[1][4] The question arises, however, whether it is still the dominant explanation because it is the best explanation, or because the community is unaware of progress on this problem.[26] In particular, in addition to the idea that Ω is not a suitable parameter in this context, other arguments against the flatness problem have been presented: if the universe collapses in the future, then the flatness problem "exists", but only for a relatively short time, so a typical observer would not expect to measure Ω appreciably different from 1;[27] in the case of a universe which expands forever with a positive cosmological constant, fine-tuning is needed not to achieve a (nearly) flat universe, but also to avoid it.[28]

Einstein–Cartan theory

The flatness problem is naturally solved by the Einstein–Cartan–Sciama–Kibble theory of gravity, without an exotic form of matter required in inflationary theory.[29][30] This theory extends general relativity by removing a constraint of the symmetry of the affine connection and regarding its antisymmetric part, the torsion tensor, as a dynamical variable. It has no free parameters. Including torsion gives the correct conservation law for the total (orbital plus intrinsic) angular momentum of matter in the presence of gravity. The minimal coupling between torsion and Dirac spinors obeying the nonlinear Dirac equation generates a spin-spin interaction which is significant in fermionic matter at extremely high densities. Such an interaction averts the unphysical big bang singularity, replacing it with a bounce at a finite minimum scale factor, before which the Universe was contracting. The rapid expansion immediately after the big bounce explains why the present Universe at largest scales appears spatially flat, homogeneous and isotropic. As the density of the Universe decreases, the effects of torsion weaken and the Universe smoothly enters the radiation-dominated era.

See also

Notes

- Since there are fluctuations on many scales, not a single angular separation between hot and cold spots, the necessary measure is the angular scale of the first peak in the anisotropies' power spectrum. See Cosmic Microwave Background#Primary anisotropy.

- Liddle[6] uses an alternative notation in which Ω0 is the current density of matter alone, excluding any contribution from dark energy; his Ω0+ΩΛ corresponds to Ω0 in this article.

References

- Peacock, J. A. (1998). Cosmological Physics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42270-3.

- Robert H. Dicke (1970). Gravitation and the Universe: Jayne Lectures for 1969. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0871690784.

- Alan P. Lightman (1 January 1993). Ancient Light: Our Changing View of the Universe. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03363-4.

- Ryden, Barbara (2002). Introduction to Cosmology. San Francisco: Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-8053-8912-8.

- Peter Coles; Francesco Lucchin (1997). Cosmology. Chichester: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-95473-6.

- Liddle, Andrew (2007). An Introduction to Modern Cosmology (2nd ed.). Chichester; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-470-84835-7.

- Ryden p. 168

- Stompor, Radek; et al. (2001). "Cosmological Implications of the MAXIMA-1 High-Resolution Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropy Measurement". The Astrophysical Journal. 561 (1): L7–L10. arXiv:astro-ph/0105062. Bibcode:2001ApJ...561L...7S. doi:10.1086/324438. S2CID 119352299.

- D. N. Spergel, et al. (June 2007). "Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Three Year Results: Implications for Cosmology". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 170 (2): 337–408. arXiv:astro-ph/0603449. Bibcode:2007ApJS..170..377S. doi:10.1086/513700. S2CID 1386346.

- Ryden p. 193

- Agazzi, Evandro; Massimo Pauri (2000). The Reality of the Unobservable: Observability, Unobservability and Their Impact on the Issue of Scientific Realism. Springer. p. 226. Bibcode:2000ruou.book.....A. ISBN 978-0-7923-6311-8.

- Collins, C. B.; Hawking, S. (1973). "Why is the Universe Isotropic?". Astrophysical Journal. 180: 317–334. Bibcode:1973ApJ...180..317C. doi:10.1086/151965.

- Barrow, John D.; Tiple, Frank J. (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-19-851949-2.

- Mosterín, Jesús (2003). "Anthropic Explanations in Cosmology". Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- Carr, Bernard J.; Rees, Martin (April 1979). "The anthropic principle and the structure of the physical world". Nature. 278 (5705): 605–612. Bibcode:1979Natur.278..605C. doi:10.1038/278605a0. S2CID 4363262.

- Castelvecchi, Davide (1981). "The Growth of Inflation". Physical Review D. 23 (2): 347. Bibcode:1981PhRvD..23..347G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.23.347.

- Guth, Alan (January 1981). "Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems". Physical Review D. 23 (2): 347–356. Bibcode:1981PhRvD..23..347G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.23.347.

- Coles, Peter; Ellis, George F. R. (1997). Is the Universe Open or Closed? The Density of Matter in the Universe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56689-6.

- Albrecht, Andreas (August 2000). Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Structure Formation in the Universe, Cambridge 1999. Nato Asic Proc. 565: Structure Formation in the Universe. 565. p. 17. arXiv:astro-ph/0007247. Bibcode:2001sfu..conf...17A. ISBN 978-1-4020-0155-0.

- Guth, Alan (1997). "Was Cosmic Inflation the 'Bang' of the Big Bang?". The Beamline. 27. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- Bird, Simeon; Peiris, Hiranya V.; Easther, Richard (July 2008). "Fine-tuning criteria for inflation and the search for primordial gravitational waves". Physical Review D. 78 (8): 083518. arXiv:0807.3745. Bibcode:2008PhRvD..78h3518B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.78.083518. S2CID 118432957.

- Chernin, Arthur D. (January 2003). "Cosmic vacuum and the 'flatness problem' in the concordant model". New Astronomy. 8 (1): 79–83. arXiv:astro-ph/0211489. Bibcode:2003NewA....8...79C. doi:10.1016/S1384-1076(02)00180-X. S2CID 15885200.

- Nikolic, Hrvoje (August 1999). "Some Remarks on a Nongeometrical Interpretation of Gravity and the Flatness Problem". General Relativity and Gravitation. 31 (8): 1211. arXiv:gr-qc/9901057. Bibcode:1999GReGr..31.1211N. doi:10.1023/A:1026760304901. S2CID 1113031.

- Anderson, P. R.; R. Schokman; M. Zaramensky (May 1997). "A Solution to the Flatness Problem via Particle Production in an Oscillating Universe". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 29: 828. Bibcode:1997AAS...190.3806A.

- Evrard, G; P. Coles (October 1995). "Getting the measure of the flatness problem". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 12 (10): L93–L97. arXiv:astro-ph/9507020. Bibcode:1995CQGra..12L..93E. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/12/10/001. S2CID 14096945..

- Holman, Marc (November 2018). "How Problematic is the Near-Euclidean Spatial Geometry of the Large-Scale Universe?". Foundations of Physics. 48 (11): 1617–1647. arXiv:1803.05148. Bibcode:2018FoPh...48.1617H. doi:10.1007/s10701-018-0218-4. S2CID 119066780.

- Helbig, Phillip (March 2012). "Is there a flatness problem in classical cosmology?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 421 (1): 561–569. arXiv:1112.1666. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.421..561H. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.20334.x. S2CID 85526633.

- Lake, Kayll (May 2005). "The Flatness Problem and Λ". Physical Review Letters. 94 (20): 201102. arXiv:astro-ph/0404319. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..94t1102L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.201102. PMID 16090234. S2CID 40500958.

- Poplawski, N. J. (2010). "Cosmology with torsion: An alternative to cosmic inflation". Phys. Lett. B. 694 (3): 181–185. arXiv:1007.0587. Bibcode:2010PhLB..694..181P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2010.09.056.

- Poplawski, N. (2012). "Nonsingular, big-bounce cosmology from spinor-torsion coupling". Phys. Rev. D. 85 (10): 107502. arXiv:1111.4595. Bibcode:2012PhRvD..85j7502P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.85.107502. S2CID 118434253.