Flying wedge

A flying wedge (also called flying V or wedge formation, or simply wedge) is a configuration created from a body moving forward in a triangular formation. This V-shaped arrangement began as a successful military strategy in ancient times when infantry units would move forward in wedge formations to smash through an enemy's lines. This principle was later used by Medieval European armies, as well as modern armed forces, which have adapted the V-shaped wedge for armored assault.

In modern times the effectiveness of flying wedge means it is still employed by civilian police services for riot control. It has also been used in some sports, although the use of wedges is sometimes banned due to the danger it poses to defenders.

Military tactics

Greeks and Romans

The wedge (έμβολον, embolon in Greek; cuneus in Latin, colloquially also caput porcinum, "boar's head"), was used by both infantry and cavalry. The men deployed in a triangular or trapezoid formation with the tip leading the way. According to Arrian and Asclepiodotus, the wedge was first used by the Scythians, and then the Thracians. Philip II of Macedon adopted it from them as the main formation of his Companion cavalry and Alexander the Great faced Persian cavalry arrayed thus, as Arrian attests. The advantage of the wedge was that it offered a narrow point for piercing enemy formations and concentrated the leaders at the front. It was easier to turn than a square formation because everyone followed the leader at the apex, "like a flight of cranes".[1]

As an infantry formation it is attested by Frontinus to have been used by the Romans in Pydna against the Macedonian line of Perseus.[2] It was also used to great effect by the Roman legions, with the wedge proving effective in campaigns in Britain, such as during Boudicca's Revolt, where a greatly outnumbered Roman army used it to defeat the Iceni.

Scandinavian and Germanic

Keilerkopf or Keil (wild boar's head, wedge, Latin: cuneus, meaning throng[3]) is a German phrase to describe the attack formation ("Tactical body") of the prehistoric infantry of the Celts and Germanic tribes. It is generally believed that the Germanic tribes were more successful with this tactic than the Celts. It was used to force the Roman forces to split and was later applied specifically to the weakest units.

Due to the high discipline this formation required and the relatively high probability of failure, it is assumed that the front lines were filled with the best and most heavily armoured warriors of the Germanic sibbs who had to break the Roman front line.

Here the individual warrior tried to gain fame and glory in the battle. The most distinguished princes and their acolytes stood at the head of the Keil. However, this was also the most dangerous point, whence the need to be heavily armoured. But an army leader who survived a lost battle often forfeited his life (usually suicide). Warriors who had fled were hanged or slain.

According to the Roman historian Tacitus, the Keil was a tightly packed crowd, strong on all sides, not only in front and back, but also on the flanks.[4] The formation was not like a wedge but more like a rectangle with forty warriors in the first line and 1,600 men strong. In this formation, the wingmen are at most risk. It was therefore well possible that the wing marched with some caution and held back a bit, so that the center stormed further and looked like a wedge. The outer ranks of the rear on the other hand swelled slightly. The goal was to hit hard at the same time and to drive a 40 yard wide hole into the enemy line, according to the German historian Hans Delbrück.[3]

According to Richard Burton, the central body consisted of heavily armed, warriors protecting less-armored archers to the sides. The triangular formation was used to overwhelm an enemy with a frontal assault. Family groups and tribes were placed side-by-side in units to maintain its cohesion in battle.[5][6] The tactic was a formidable assault strategy against defenders in line or column, however, attackers faced annihilation in the event of retreat because the wedge became an ill-defined mob if its forward momentum collapsed.[6][5]

When the Germanic Keil was advancing against the enemy, they sang the baritus or barditus, the battle song (battle cry); it begins with a muffled grumbling and swells with the heat of the battle up to the roar of the waves beating against the rocks. According to Germanic legend and Tacitus, Hercules once visited German soil and they sang of him first of all heroes.[7]

The Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the tactic was especially effective against defensive shield wall formations when defenders would link their shields together to form an all-but impenetrable barrier. Armored, heavily armed infantry could use their momentum in wedge formation to drive open small sections in the shield wall. This would break up the shield wall exposing the defenders to flank attacks.

Western Europe

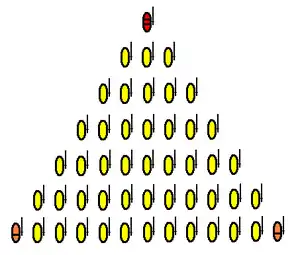

Two complete descriptions of an infantry wedge are given by Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum. In Book I, he describes a shallow wedge, with the front rank of two men then each thereafter doubled. In Book VII, he depicts a sharper pointed formation 10 men deep with the first rank being composed of 2 men, each rank composed of 2 more.[8] Thus, each wedge was composed of 110 men, 10 deep, 2 men on its tip, and 20 on its base. According to the Vikings, the wedge formation, called by them svinfylking, cf. the Latin caput porcinum, was invented by Odin himself.[9]

A triangular or wedge formation was also used in the medieval period by the Flemish and Swiss infantry.[10]

Deep wedges of cavalry were used by German armies in the later Middle Ages. At the Battle of Pillenreuth in 1450, both the armies of Albrecht Achilles and Nuremberg fought in wedge formation. The Nuremberg cavalry was drawn up in a wedge led by 5 picked knights, then seven, then nine, then 11. The following twenty ranks held 250 ordinary men-at-arms, then a final rank of 14 picked men to hold the formation together.[11] Sir Charles Oman refers to an unpublished manual of 1480 by Philip of Seldeneck[12] which describes the formation, calling it the Spitz. He gives examples of various formations varying from 200 men to 1000. The formation of 1000 men places seven men in the first rank, with each rank increasing by two men back to the eighth rank with 21. The remaining men are in a column 20 men wide behind the point. The banner would be carried in the seventh rank.

Byzantium

Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros Phocas analyzes the wedge formation of the Byzantine Cataphracts in the third chapter of his Praecepta Militaria. There, he relates that the wedge must be formed by 354 cataphracts and 150 horse archers to a total number of 504 men. The row of the first line comprised 20 horsemen, the second 24, the third 28, down to the 12th line, which consisted of 64 men. If such a number of men is not available, he proposes that the wedge be formed by 304 cataphracts and 80 horse archers, or a total of 384 men, the first line comprising 10 men. In his next chapter (Ordinance on Cavalry Deployment), he ordains that the wedge must be accompanied by two cavalry units, which will guard its flanks. A wedge whose ranks are not complete in the middle is shaped as an Λ instead of a Δ and is called a hollow wedge, or in Greek κοιλέμβολον, koilembolon.

Modern warfare

The wedge is still used in modern armies, especially by tanks and other armored units. An example of this is the Panzerkeil or "armored wedge" used by the Germans in World War II.

The hollow wedge formation remains one of the basic infantry formations at the squad and section level, especially when crossing open ground. However unlike in ancient and medieval times, the formation is used not to maximise effectiveness in melee combat, but to maximise the situational awareness and firepower of a unit. The intervals between soldiers is designed to give mutually supporting lines of sight that do not obscure one another forward and to the sides, and this also corresponds to mutually supporting overlapping arcs of fire. The squad automatic weapon will usually anchor one of the flanks of a fireteam wedge. In a platoon wedge the command group and platoon machine guns are placed in the hollow of the wedge.

Exactly the same principles of mutually supporting lines of sight and fire, apply to an armored vehicles deployed in a wedge formation.

Drill formation

The wedge formation is used ceremonially by cadets at the United States Air Force Academy during the annual graduation parade, when the soon-to-be commissioned first-class cadets (seniors) leave the Cadet Wing. This is the reverse of the acceptance parade, held each fall, when the new fourth-class cadets (freshmen) join the Cadet Wing in the inverted wedge formation.

Civilian applications

Policing

Police riot squads sometimes charge in flying wedge formations, to break into a dense crowd as a snatch squad to arrest a leader or speaker, or to chop a long demonstration march into segments. It can also be used to escort VIPs through hostile crowds.

Sports

Although originally permitted in most full contact team sports, the use of the flying wedge is now banned for safety reasons in rugby union,[13] rugby league,[14] and American football.[15] The principle is similar to the military application: the ball carrier starts an attack and is joined on both sides by teammates who drive them forward towards the goal line. However due to the number of deaths and serious injuries related to the flying wedge, any attempt at this formation is now punished by in-game penalties.

In American football, the formation was developed by Lorin F. Deland and first introduced by Harvard in a collegiate game against Yale in 1892. Teammates would lock themselves together with the ball carrier using their hands and arms and rush forward. But despite its practicality, it was outlawed two seasons later in 1894 because of its contribution to serious injury.[16] The penalty against assisting the runner, which forbids the locking together of players as well as pushing and pulling the ball carrier to increase force in the same manner as the historic flying wedge, remains in the American football rule books; its eradication has been so complete that the foul has not been called in the National Football League since 1991.[17] The concept of wedge-shaped formations concept continued to influence several football plays in the modern game, particularly on kickoff returns, until 2009 when NFL league owners agreed to stop its use.[15] Recent changes in the rules at various levels regarding runbacks of free kicks are stricter still in that they restrict blocking by teammates close together even without touching each other. The "wedge" commonly referred to in interference on free kick returns simply meant such a close group of blockers.[18] Wedge blocking using only the shoulders to push forward teammates not holding the ball is still legal. Professional and Canadian football went still farther in theoretically not allowing any transfer of momentum between teammates in blocking but that prohibition is not strictly enforced.

Notes

- Lendon, J.E. (2006) Soldiers and Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity, Yale University Press, p. 98.

- Frontinus, Stratagems, II.iii.20

- The Germanic warriordom (German) Hans Delbrück, 1920, History of warfare in the framework of political history, Part 2 The Teutons, Book 1 The struggle of the Romans and Teutons, Chapter 2 The Germanic warriordom ISBN 0-8371-8163-1

- Tacitus, Hist. IV, 20

- "Quodque præcipuum fortitudinis incitamentum est, non casus, nec fortuita conglobatio turmam aut cuneum facit, sed familiæ et propinquitates" - Tacit. Germ. 7. Refer Germania (book)

- Richard F. Burton (1987). "CHAPTER XIII. THE SWORD AMONGST THE BARBARIANS (EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE)". Book of the sword. Dover Publications; Revised ed. edition. ISBN 0486254348.

- Tacitus, Germania III, Hist. II, 22, Hist. IV, 18.

- "The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus", translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905)

- Peter G. Foote and David M. Wilson, The Viking Achievement (New York, 1970),p.285

- Contamine, Philippe (1984). War in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 231–2. ISBN 0-631-13142-6.

- Delbrück, Hans; Trans Walter J. Renfroe (1990) [trans 1982]. History of the Art of War vol III; The Middle Ages. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood. p. 275. ISBN 0-8032-6585-9.

- Oman, Sir Charles (1987) [1937]. A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. London: Greenhill. pp. 82–3. ISBN 0-947898-69-7.

- Section 4(n) of Law 10 of Rugby Union Archived 2007-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Harris, Bret (18 February 2011). "Rod Macqueen to get edge with wedge". The Australian.

- Battista, Judy (24 May 2009). "Mindful of Violence, the N.F.L. Rules Out the Wedge Formation". The New York Times.

- Introduction: A Brief History of College Football

- When is it a foul for pulling a ball carrier forward? FootballZebras.com, November 2019.

- "No wedge means major adjustment for kickoff units" NFL.com

External links

- "Infantry Squad Operations:Movement". global security.org. United States Army Infantry Training School. January 1996. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- Chinese riot police show off their skills in breaking up a demonstration