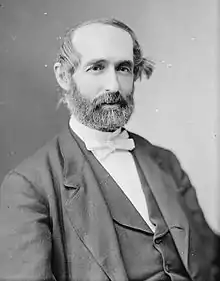

Frederick W. Seward

Frederick William Seward (July 8, 1830 – April 25, 1915)[1] was an American politician and member of the Republican Party who twice served as the Assistant Secretary of State. The son of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, he served as Assistant Secretary from 1861 to 1869 under both Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson and then from 1877 to 1879 in the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Frederick W. Seward | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th & 11th United States Assistant Secretary of State | |

| In office March 16, 1877 – October 31, 1879 | |

| President | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Preceded by | John Cadwalader |

| Succeeded by | John Hay |

| In office March 6, 1861 – March 4, 1869 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865) Andrew Johnson (1865-1869) |

| Preceded by | William H. Trescot |

| Succeeded by | J.C. Bancroft Davis |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Frederick William Seward July 8, 1830 Auburn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | April 25, 1915 (aged 84) Montrose, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Wharton Seward

(m. 1854; |

| Relations |

|

| Parents | Frances Adeline Seward William H. Seward |

| Alma mater | Union College |

| Profession | Lawyer, writer, editor, politician |

| Signature | |

Early life

Seward was born in Auburn, New York on July 8, 1830. He was the son of Frances Adeline (née Miller) Seward and William H. Seward, who shortly after his birth became a New York State Senator (and later the 12th Governor of New York, a U.S. Senator and the 24th United States Secretary of State). Frederick was the younger brother of Augustus Henry Seward and the elder brother of General William H. Seward Jr. and Fanny Seward.

His maternal grandfather was Judge Elijah Miller and his paternal grandfather was Judge Samuel S. Seward, who was also a physician and member of the New York State Assembly.

From 1839 to 1840, while his father was Governor of New York State, Frederick attended the Pearl Street Academy in Albany, New York.[2] He graduated from Union College in 1849,[3] and studied law with Henry E. Davies and William Kent. In 1851, he was admitted to the bar in Rochester, New York. In 1878, Union awarded him an honorary LL.D. degree.[1]

Career

After graduating from college, Seward served as a secretary to his father from 1849 to 1857, and served as associate editor of the Albany Evening Journal from 1851 to 1861.[4]

Baltimore Plot

On February 21, 1861, Seward arrived at the Continental Hotel in Philadelphia carrying a letter from his father for President-elect Lincoln. The letter contained information gathered by Colonel Charles Pomeroy Stone and General Winfield Scott.

Stone had stationed three detectives from the New York police department in Baltimore, Maryland to gather information about plots against Lincoln. Making his way by train from Illinois to Washington for his inauguration, Lincoln had intended to stop next at Baltimore, which was home to many secessionist sympathizers. According to information gathered by Stone's detectives, secessionists were planning to assassinate Lincoln during his stop in Baltimore.

The warning Fred Seward brought would contribute to Lincoln's decision to pass through Baltimore under the cover of night, rather than stop and appear in public there. Although Allan Pinkerton also warned Lincoln of danger awaiting him in Baltimore, it was Seward's information that confirmed everyone's fears.

Civil War

When his father was appointed Secretary of State in 1861, Seward became Assistant Secretary of State in charge of consular service under Lincoln and Andrew Johnson. He served in the position until 1869 and "assisted in the negotiations to the adoption of the Burlingame Treaty," which set the attitude towards China when the empire "accepted the principles of international law."[1]

Attempt on father's life

On April 14, 1865, he was injured in an assassination attempt upon his father on the same night that Lincoln was murdered. Lewis Powell, also known as "Lewis Paine," an ex-Confederate co-conspirator of John Wilkes Booth attempted to kill William Seward while the Secretary of State was convalescing at home from a carriage accident.

That was Powell's part in the plot to put the government into chaos; Vice President Andrew Johnson and President Lincoln were also to be killed that same evening. After Frederick blocked Powell from gaining access to William Seward's bedroom, Powell tried to shoot Frederick in the head. However, when the gun failed to fire, Powell quickly smashed the pistol over Frederick's head, causing several skull injuries. Frederick then collapsed and fell to the floor at the top of the stairs.

Powell then burst into William Seward's room and stabbed him several times in the face and neck. Powell also injured a number of other bystanders, including Frederick's sister Fanny, his brother Augustus, his father's nurse Private George F. Robinson and messenger Emerick Hansell, but no one was killed. Seward's mother was sure that he was going to die; instead, she died on June 21, 1865 of a heart attack. His sister, Fanny, died soon afterward, in October 1866.

Powell was hanged on July 7, 1865, along with David Herold, George Atzerodt, and Mary Surratt, who were also involved in the conspiracy.

Later life

Frederick's father died on October 10, 1872. Seward was a member of the New York State Assembly (New York Co., 7th D.) in 1875.[5] At the New York state election, 1875, he ran on the Republican ticket for Secretary of State of New York,[6] but was defeated by Democrat John Bigelow. He served again as Assistant Secretary of State under William M. Evarts from 1877 until his resignation in November 1879 due to illness.[7] Seward was replaced by John Hay, the diplomat who was one of President Lincoln's former private secretaries.[7]

Seward also edited and published his father's autobiography and letters in a volume entitled Life and Letters of William H. Seward.[8] Mostly, his life after 1881 was devoted to the practice of his legal profession and to lecturing and writing.

Personal life

On November 9, 1854 he married Anna Margaret Wharton (1836–1919) of Albany, New York and spent the latter part of his life in a house he built in Montrose-on-the-Hudson,[9] near Peekskill, in New York.[8] The estate had nearly a mile of Hudson River water-frontage.[10]

Seward died at his home in Montrose on April 25, 1915, at the age of 84.[1] He was interred with his family in Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York.[11] Seward left an estate valued at $100,000.[12] In 1916, a year after his death, his book Reminiscences of a War-Time Statesman and Diplomat, 1830-1915, a five-hundred page book about the Civil War and politics, was published by G.P. Putnam's Sons.[13] Also in 1916, his widow sold their 50-acre Montrose estate.[10]

References

- "F. W. SEWARD DEAD; FRIEND OF LINCOLN; Son of Civil War Secretary of State Expires in Auburn, N. Y., at Age of 84. EDITOR, AUTHOR, DIPLOMAT Warned President-Elect of Plot to Kill Him -- Beaten by Assassin Who Stabbed Father" (PDF). The New York Times. April 26, 1915. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Reminiscences of a Wartime Statesman and Diplomat. G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1916, p. 31.

- "Seward's Lecture at Union College" (PDF). The New York Times. November 19, 1892. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "William Henry Seward Papers". rbscp.lib.rochester.edu. University of Rochester. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Reconstruction.; President Lincoln's Plan Speech of Hon. Frederick W. Seward in the Assembly" (PDF). The New York Times. January 17, 1875. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "The State Ticket; Frederick W. Seward" (PDF). The New York Times. October 30, 1875. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Frederick W. Seward Resigns" (PDF). The New York Times. November 15, 1879. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Biographical Directory of the State of New York, 1900. Biographical Directory Company (incorporated). 1900. p. 435. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Barnes, William; Seward, Frederick William (1904). Semi-centennial of the Republican Party: Proceedings at the Celebration at Saratoga Springs, September 14, 1904 : Speeches by Frederick W. Seward ... J. B. Lyon Company. p. 27. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "LATEST DEALINGS IN THE REALTY FIELD; Fifty-Acre Estate of the Late Frederick W. Seward at Montrose, N.Y., Sold. SALE IN GREENWICH VILLAGE Big Loft for Chelsea District Leased from the Plans at Aggregate Rental of $325,000" (PDF). The New York Times. March 12, 1916. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Frederick W. Seward Buried" (PDF). New York Times. April 29, 1915. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

The funeral of Frederick W. Seward, formerly Assistant Secretary of State in the cabinets of Presidents Lincoln, Buchanan and Hayes and son of Secretary ... in Fort Hill Cemetery.

- "F. W. SEWARD LEFT $100,000.; Estate of Lincoln Administration Official Goes to Widow" (PDF). The New York Times. June 8, 1915. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Seward, Frederick William (1916). Reminiscences of a War-Time Statesman and Diplomat, 1830-1915. New York and London: G. P. Putnam's sons. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

Further reading

- Saving Mr. Lincoln: CIA Site by CIA 2007

- EHistory at OSU | Online Books | Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume 1 Page 022 at ehistory.osu.edu Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 1, Ohio State University Online

- Seward, William Henry at www.library.rochester.edu The University of Rochester Library: Rare Books and Special Collections

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frederick W. Seward. |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William H. Trescot |

United States Assistant Secretary of State March 6, 1861 – March 4, 1869 |

Succeeded by J.C. Bancroft Davis |

| Preceded by John Cadwalader |

United States Assistant Secretary of State March 16, 1877 – October 31, 1879 |

Succeeded by John Hay |