Freedom of the press in Peru

Peru has established democratic political institutions that indicate an improvement in their press freedom environment as corruption continues to be a concern.[1] There have been multiple shifts in the level of freedom of the press in Peru, starting in the late 1900s when the country was not free, to the early 2000s where the country was free; Only recently has the country been ranked as partly free.[1] Peru's political system and its changing political status has affected its overall press freedom.

History

The following major historical events reveal the influence of political figures and historical events on the country's press freedom environment.

The period of military rule (1968-80)

Press freedom in Peru underwent its worst stage during the military regime, also known as the Peruvian Military Junta, led by Juan Velasco Alvarado in the years 1968 to 1980. The major impact of this political system in Peru was the closing and censorship of broadcast and print news media, as Velasco implemented a new press law demanding the expropriation of all national newspapers in 1974.[2] Newspapers were closed and publishers were sent into exile due to accusations about distorting and influencing the public.[2][3] Multiple newspapers were not closed but Velasco expropriated the country's major newspapers, as well as the main television channels and radio stations.[3] Only those media platforms that shared the regime's main aim, to align the means of communication with the social interest of Velasco, remained working.[3] Velasco decided to use government-appointed bureaucrats to look over the articles being published[3] such that the papers published resembled the military regime's principles.Hector Cornejo Chavez was one of the figures appointed to overlook El Comercio as he was one of Velasco's must trusted advisers.[3] Even though Velasco managed to hide opposing opinions on the regime coming from newspapers or mass media platforms, a few independent press managed to survive throughout the late 1970s.[2]

The Fujimori decade (1990-2000)

Peru underwent an internal war characterised by the rising of the Shining Path's guerrilla, sabotage and terrorist actions, and again Peru was put under military rule.[3] Peruvian journalists continued to have problems of freedom of the press concerning economic instability and threats from the growing guerrilla movements, until a Japanese descended president, Alberto Fujimori, took power after the 1992 coup d’état.[3] Fujimori put private property and market in the centre of the country's development.[2] The constitution turned from a democracy into an authoritarian regime in 1992.[2] Mainly the newspapers were impacted as troops occupied the newspaper buildings, forcing journalists to show them the work before publishing it.[2] Fujimori requested for the troops to leave the buildings and visited El Comercio to apologize for their actions in the portrayal of their authoritative regime as a dictatorship, while also mentioning the existence of unrestricted press freedom in Peru.[3] Fujimori did not intervene directly since most media platforms agreed with his objectives, thus maintaining the regime's stability. However, media interventions played a role in bringing down Fujimori, revealing the incompatibility of a free press and a dictatorship in Peru.

Contemporary democracy (since 2000)

Since the end of Fujimori's regime, there has been a recovery democracy that influenced the freedom of the press in Peru.[2] There are several occasions that reveal the aim for a democracy. In 2001, president Alejandro Toledo tried to eliminate corruption in order to restore press freedom[2] in which the government introduced a law three years later that allowed for the freedom of expression, press freedom and media. In 2011, a bill that eradicated jail time for defamation and replaced it with fines and community service, revealed a small progress toward achieving completely press freedom.[4] However, in December 2012, public access to information about national security and defense was denied,[4][5] along with a new cyber crime legislation introduced in October 2013, which reduced the use of government data.[5] There has been multiple shifts in the laws that apply to journalists being able to gather data. Despite the existence of access to information laws as Peru is a democratic country, transparency regarding official documents are inconsistent in practice and journalists face difficulties when gathering information and when publishing articles in all media platforms.[5]

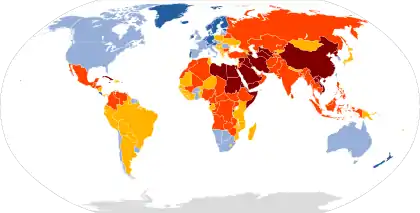

2018's Ranking of Peru's press freedom

The 2018 World Press Freedom Index shows a slight overall improvement in respect for press freedom in Latin America.[6] However, Latin American countries such as Peru still suffer recurring problems of violence, impunity and authoritarian policies towards citizens that work as journalists.[6]

Peru occupies the 88th position of 180 listed countries all over the world when it comes to press freedom, with the lowest number in the ranking being the countries with more press freedom, according to the 2018 World Press Freedom Index.[7] Peru also occupies the 6th position out of 12 countries in South America, according to the latest World Press Freedom Index 2018.[8] Each index reflects the level of freedom available to journalists, as the researchers reported it is based on an evaluation of the independence of media, pluralism and the quality of legislative framework and safety of journalists in each country.[9]

As the rankings show, Peru continues to have noticeable problems when talking about press freedom as media freedom is threatened by the press laws that allows for journalists to be punished with imprisonment, and for expanding news that can damage the reputation of a company, person or the government.[9] Hence journalists must avoid topics such as corruption, social conflicts or drug trafficking.[9]

Attacks, threats and murders against Peruvian journalists

In Peru, there is a complicated environment for journalists. These cases reveal the risk of being a journalist in Peru.[10]

| Journalist | Year | Date | Position of employment | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hugo Bustíos | 1988 | 24 November | Worked at the News Magazine titled Careta and was thePresident of the National Association of Journalist of Huanta.[11] | The Peruvian armed forces of Ayacucho were the ones who murdered Hugo Bustíos. Daniel Urresti, the mayoral candidate, was acquitted for his assassination.[11] |

| Flores Silva | 2011 | 9 September | She was the program's Director of the television program aired in Channel 6 named Visión Agraria.[12] | Shot dead while riding a motorcycle. The journalist denounced the corruption in the public administration of the mayor of Casma, who had sued the journalist several times.[12] |

| Donny Buchelli Cueva | 2016 | 8 July | He was the owner of the Solimar radio Station and also hosted Más Radio.[5] | He was tortured in his house until he died. At that time, 2016, the journalist was writing and criticizing the transparency of multiple local electoral candidates.[5] |

| Gloria Lima Calle | 2014 | 17 October | She was journalist Gerson Fabián Cuba's wife.[5] | She was killed while defending her husband from gunmen that broke into the offices of radio Rumba where her husband hosted a program. Recently, Fabián had covered controversial topics on his radio program, such as corruption and criticism about the protests against an energy company, named Pluspetrol.[5] |

| Fernando Raymondi | 2014 | 9 November | He was a journalism student and a writer of the well-wknown newspaper Caretas.[5] | Shot and killed at his father's grocery store in Lima, because he was writing a story about the different murders that local gangs committed.[5] |

| Marco Bonifacio Sánchez | 2017 | 7 February | He was a host of the radio and television program El Canillita. | Vandals tried to cut his tongue while walking in Cajamarca, Peru. The journalist was recognized for his critical style against official authorities and institutions.[13] |

| José Feliciano Yactavo Rodríguez | 2017 | 27 February | Producer and Director of documentaries.[14] | Found inside a suitcase that had been previously burnt.[14] |

| Juan Berríos Jiménez | 2018 | 6 January | Owner of the Tahuamanu radio station.[15] | Murdered because he reported corruption issues and the misuse of community funds.[15] |

See also

References

- "Peru". freedomhouse.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "Peru - MEDIA FREEDOM". MEDIA FREEDOM. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- Gorriti, Gustavo (1993). "Living Dangerously: Issues of Peruvian Press Freedom". Journal of International Affairs. 47 (1): 223–241. JSTOR 24357093.

- "Peru". Free Speech and Free Press Around the World. 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "Peru". freedomhouse.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "RSF Index 2018: Mixed performance in Latin America". RSF (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "Country Profile Peru". Media Ownership Monitor. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "2018 World Press Freedom Index | Reporters Without Borders". RSF. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- Summer, Eva. "Middle ranking for Peru regarding freedom of the press". PeruTelegraph. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "The other face of press freedom in Peru". International Press Institute. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "Peru mayoral candidate Daniel Urresti acquitted of Hugo Bustíos murder". cpj.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- Internet, Unidad Editorial. "Organizaciones internacionales condenan el asesinato de un periodista en Perú | Noticias | elmundo.es". www.elmundo.es. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "Sujetos atacan a periodista peruano e intentan cortarle la lengua - Committee to Protect Journalists". cpj.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "La Directora General de la UNESCO denuncia el asesinato del periodista peruano José Feliciano Yactayo Rodríguez". UNESCO (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- "Attackers set fire to car of Peruvian radio journalist". cpj.org. Retrieved 2018-11-30.