French Renaissance architecture

French Renaissance architecture is a style which was prominent between the late 15th and early 17th centuries in the Kingdom of France. It succeeded French Gothic architecture. The style was originally imported from Italy next after the Hundred Years' War by the French kings Charles VII, Louis XI, Charles VIII, Louis XII, and François I. Several notable royal châteaux in this style were built in the Loire Valley, notably the Chateau de Montsoreau, the Chateau de Langeais, the Chateau d'Amboise, the Chateau of Blois, the Chateau of Gaillon, and the Chateau of Chambord, and, closer to Paris, the Château de Fontainebleau.

Top: Château de Chambord; Château de Chenonceau: Center: Azay le Rideau; Château de Fontainebleau; Bottom: Lescot Wing of Louvre | |

| Years active | late 15th – early 17th centuries |

|---|---|

This style of French architecture had two distinct periods. During the first period, between about 1491 and 1540, the Italian style was copied directly, often by Italian architects and craftsmen. In the second period, between 1540 and the end of the Valois dynasty in 1589, French architects and craftsmen gave the style a more distinctive and original French character.[1]

The major architects of the style included the royal architects Philibert Delorme, Pierre Lescot and Jean Bullant, and the Italian architect and architectural theorist Sebastiano Serlio.[2][3]

History – the Italian period

During the Hundred Years' War, Charles VII found the Loire Valley an ideal place of refuge. He was crowned in Reims following the Johan of Arc epic battles that began the departure of the English from the whole kingdom. The middle of the 15th century was a key period for the Loire Valley in the history of France and its architectural heritage. The greats of the kingdom settled in the region, fitting out medieval fortresses or erecting new buildings. Charles VII resided in Chinon, which remained the seat of the court until 1450, and he and his dauphin, the future Louis XI, ordered or authorized construction works to be carried out. Then began the construction of the Châteaux of the Loire Valley.

Thus, from 1443-1453, the main building of the Chateau de Montsoreau is built on the Loire river banks by Jean II de Chambes, diplomat in Venice and in Turkey and private counselor of King Charles VII. Between 1465 and 1469, Louis XI ordered the construction of the Chateau de Langeais at the end of the promontory, a hundred meters in front of the 10th century dungeon.[4] In 1494, Charles VIII led a large army into Italy to capture Naples, which had been seized by Alfonso V of Aragon. He passed through Turin, Milan and Florence, and retook Naples on 22 February 1495. In that city he discovered the lavish gardens and the new architectural style of the Italian Renaissance, which he judged far superior to that of his own medieval palace in Amboise. An anti-French coalition of armies forced him to retreat from Naples, but he took with him twenty-two skilled Italian craftsmen, including gardeners, sculptors, architects and engineers, including the scholar and architect Fra Giocondo and the architect and illustrator Domenico da Cortona, whom he assigned to remake his chateau in Amboise.[5]

Château de Montsoreau (1450–1461)

In 1453, at the end of the Hundred Years' War, Charles VII authorized the construction of the Château de Montsoreau by Jean II de Chambes, then diplomat in Venice and Turkey and private adviser to the king. It was built on the site of the ancient fortress of Foulques Nerra, unusually, directly on the Loire river bank in the style of Venetian Renaissance. Its architecture is of transition between military and pleasure architecture and bears witness to the time when castles became châteaux. The main building was built in 1453 and in an unprecedent manner, two square pavilions were added between 1453 and 1461, anticipating the classical architecture by several decades. Jean III de Chambes built or transformed the grand stairway tower in the Italian style in 1510–1515, its carvings are similar to the ones of the gate-house of Chateau de Gaillon.[6]

Plan of Montsoreau by Marquis de Geoffre

Plan of Montsoreau by Marquis de Geoffre Aerial view of the site

Aerial view of the site Loire facade of the chateau

Loire facade of the chateau Grand stairway Renaissance tower (circa 1510)

Grand stairway Renaissance tower (circa 1510) High lucarnes flanked by pinnacles on the roof

High lucarnes flanked by pinnacles on the roof

Château d'Amboise (1491–1498)

In 1491, before the Italian campaign, Charles VIII had begun rebuilding the Château d'Amboise, turning it from a medieval castle into a more comfortable residence, with two wings and a chapel. He returned from Italy to Amboise in March 1496, where nearly two hundred stonemasons and ninety other skilled craftsmen were already at work. Much of the building was already done in the earlier Medieval style, with high lucarnes flanked by pinnacles on the roof. The first Renaissance additions were the large bays on the ground floor, which opened out with a view of the Loire. Amboise also had, on the Hurtault tower, some of the first Renaissance pilasters in France, sculpted columns on the wall that were purely decorative. The landscape architect whom Charles brought from Italy, Pacello da Mercogliano, created the first French Renaissance garden on the terrace, surrounded by a forged wrought iron fence. Charles did not see the château completed; he died there in 1498, after accidentally hitting his head on a lintel.[7]

Plan of Château d'Amboise by Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau

Plan of Château d'Amboise by Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau The Château beginning the transition from Medieval to Renaissance (1491–98)

The Château beginning the transition from Medieval to Renaissance (1491–98).jpg.webp) Renaissance ornamental pilaster attached to the medieval Tour Heurtault

Renaissance ornamental pilaster attached to the medieval Tour Heurtault The wide bays opening on the terrace were a Renaissance feature

The wide bays opening on the terrace were a Renaissance feature Gardens of the Château

Gardens of the Château

Château de Gaillon and Château de Bury

Not all the architectural innovation took place in the Loire Valley. Georges d'Amboise was archbishop of Rouen, but also the chief minister for Italian affairs for both Louis XII and Charles VIII. Between 1502 and 1509 he largely redecorated his residence in the valley of the Seine, the Château de Gaillon, in the Italian style. He acquired a fountain, marble medallions from Genoa, sculpted frontons and pilasters with seashell ornamentation, and various architectural elements from Italy and used them in the chậteau. Gradually, the decoration transformed the château from a medieval fortress to an elegant Renaissance residence. Most of the Château was demolished in the 19th century, but some portions remain and some of the decoration is now on display in the Musée national des Monuments Français in Paris.[8]

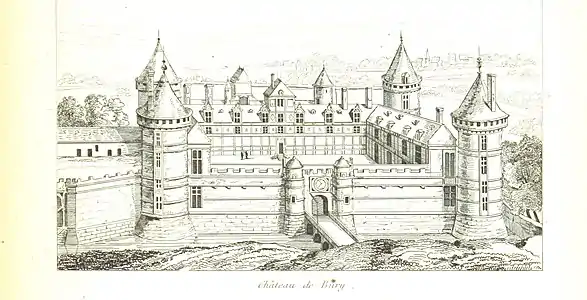

The Château de Bury, another medieval castle (since demolished), was constructed beginning in 1511 by Florimond Robertet, a state secretary and treasurer for both Charles VIII and François I. Following the new style, it was designed for living, not for fighting. It was perfectly symmetrical, with four round towers, around a central cour d'honneur, which was decorated with a statue of David by Michelangelo. A double stairway on the exterior at the main entrance replaced the traditional winding stairway within a tower. The facade was largely vertical, but was divided by horizontal cordons or bands of decoration following the style of palaces in Florence and Rome. This symmetrical balance of horizontal and vertical lines became a prominent feature of the French Renaissance style.[9]

Window decoration of Château de Gaillon

Window decoration of Château de Gaillon Italian Renaissance window decoration in Château de Gaillon (1502–1509)

Italian Renaissance window decoration in Château de Gaillon (1502–1509) Château de Bury (begun 1511)

Château de Bury (begun 1511)

Château d'Azay-le-Rideau (1518–1527)

As the French Court settled in Loire Valley, the courtiers and ministers built or rebuilt palatial residences nearby. The Château d'Azay-le-Rideau (1518–1527) was constructed on an island in the Ile River by Gilles Berthelot, a wealthy banker from Tours, who was president of the Chamber of Accounts, Receiver-General of Finances, and Treasurer of France. From 1518 to 1524, dykes were built to stabilize the foundations. The towers were placed at the corners of the building, with an interior walkway around the building and a horizontal band between the two floors; a high roof and lucarnes, or dormer windows, which rose above the roofline and framed with pediments and topped with ornate windows with pediments which rose above the roof level, which became the most recognizable feature of French Renaissance architecture. The double doorway was constructed like a small arch of triumph. The grand stairway, in the Italian style, was the most important interior feature; it had a coffered ceiling decorated with sculpture.[10]

Chateau d'Azay-le-Rideau (1518–1527)

Chateau d'Azay-le-Rideau (1518–1527).jpg.webp) The grand stairway of the Cháteau, the centerpiece of the facade

The grand stairway of the Cháteau, the centerpiece of the facade Window with a lucarne, raised above the roof and framed with sculpted pilasters, characteristic of French Renaissance style

Window with a lucarne, raised above the roof and framed with sculpted pilasters, characteristic of French Renaissance style Coffered ceiling of the grand stairway

Coffered ceiling of the grand stairway

Château of Blois (1519–1536)

The Château de Blois (1519–1536) was originally begun by Louis XII of France, cousin and successor to Charles VIII. The original design was more medieval than Renaissance; only the pillars and decorated capitals of the columns on the courtyard, and the sculpture in light relief, showed the Italian influence.

The arrival of François I in Blois, accompanied by his court and a large contingent of artists, made that château the centre of the French Renaissance. It became his principal residence and he devoted much of his effort on rebuilding the north wing, called the Loges, where his apartments were located. The architecture was inspired by the design of Donato Bramante for the Cortile del Belvedere of the Vatican Palace in Rome. Its facade facing the courtyard presented arcades and niches decorated with pilasters in the Italian style, but it was left unfinished. One characteristic feature of François I decoration at Blois was the corniche aux coquilles, a cornice with a sea shell motif.[11]

Château de Blois courtyard facade with circular stairway and lucarnes along the roof

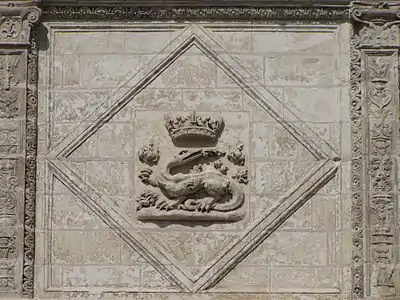

Château de Blois courtyard facade with circular stairway and lucarnes along the roof A sculpted salamander, the emblem of François I, on the facade of the north wing

A sculpted salamander, the emblem of François I, on the facade of the north wing_(12883077533).jpg.webp) Roofline decoration and lucarne of the François I wing

Roofline decoration and lucarne of the François I wing

Château de Chambord (1519–1538)

The Château de Chambord was the summit of the early French Renaissance style, a harmonious combination of French tradition and Italian innovation. François I conceived the idea of a comfortable hunting lodge in the forest. Work began in 1519, but was interrupted by the capture of the King by the Spanish-Imperial army at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. It resumed in 1526 after the King was released, and was finished in 1538. Leonardo da Vinci was a resident and died at Chambord in the same year that construction began, and may have played a part in designing the unique double spiral stairway.[12]

The plan of the Chateau is that of a medieval fortress, with round towers on the corners and massive keep or central tower, but the exuberant ornament is purely early French Renaissance.[13][14] The facade has pilasters at regular intervals, balanced by horizontal bands of relief sculpture. The roof is bristling with lucarnes, chimneys and small towers. The interior is symmetrical; the large central open space had as is centrepiece, the double spiral stairway. Ornament inspired by northern Italy predominates in the interior, in the form of a vaulted ceiling with carved decoration in each vault; sculpted capitals on the columns; and cul-de-lampes, or sculpted decoration on the base of columns and arches where they met the wall.[15]

Facade of the Château de Chambord (1519–1538)

Facade of the Château de Chambord (1519–1538) The double-spiral stairway at Chambord

The double-spiral stairway at Chambord A lucarne or dormer window at Chambord

A lucarne or dormer window at Chambord_(13007720825).jpg.webp) Sculpted vaulted ceiling at Chambord

Sculpted vaulted ceiling at Chambord Detail of the roof of Chambord, with lucarnes, chimneys, and small towers around the central lantern tower

Detail of the roof of Chambord, with lucarnes, chimneys, and small towers around the central lantern tower

The Château de Fontainebleau

After he was released from his captivity in Spain in 1526, François I decided to move his court from the Loire Valley to the Ile-de-France region centered in Paris. He constructed or reconstructed seven châteaux in the Ile-de-France, the most important of which was the Château de Fontainebleau.[16]

The architect the King chose for Fontainebleau was Gilles Le Breton. Work commenced in 1528 with the remodeling of the medieval oval courtyard. The 12th-century tower was preserved, and a new residential block was constructed, its facade ornamented with pilasters and high windows with lucarnes and with triangular frontons, which became a signature feature of the new style. The old medieval chatelet, or gatehouse, was replaced by a new structure, the Porte Dorée, which was composed of grand loggias one above the other, modeled after the palaces of Naples and Urbino.[17]

The second phase was new courtyard, the Cheval Blanc, with three long wings constructed of brick and moellons et enduit, a mixture of rubble and cement, which became a common combination in French Renassiance architecture. The round medieval towers of the old Chateau were replaced by square pavilions with high roofs and lucarne windows. The third phase was a new gallery to connect the old and new buildings. The decor of this new gallery was created by a Tuscan craftsman, Rosso Fiorentino. who arrived in 1530. The final new project was a grand stairway on the oval court leading up the royal apartments. It had a portico with classical columns resembling a triumphal arch. The design of this stairway was not borrowed from Italy, but copied directly from classical Roman models. It was a sign of the beginning of more originality in French Renaissance architecture.[18][17]

The Porte Dorée, or gatehouse, with large loggias one above the other, and lucarne windows with triangular frontons

The Porte Dorée, or gatehouse, with large loggias one above the other, and lucarne windows with triangular frontons.JPG.webp) The François I Gallery at the Palace of Fontainebleau (1533–1539)

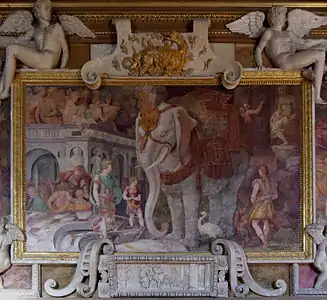

The François I Gallery at the Palace of Fontainebleau (1533–1539) An elephant by Rosso Fiorentino, illustrating the mixed sculptural and painted decoration in the François I Gallery of Fontainebleau

An elephant by Rosso Fiorentino, illustrating the mixed sculptural and painted decoration in the François I Gallery of Fontainebleau The horseshoe stairway was originally built for Henry II by Philibert Delorme between 1547 and 1559, then rebuilt for Louis XIII by Jean Androuet du Cerceau in about 1640.

The horseshoe stairway was originally built for Henry II by Philibert Delorme between 1547 and 1559, then rebuilt for Louis XIII by Jean Androuet du Cerceau in about 1640.

Beginning in 1530, the group of Italian artists imported by François I, led by Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Primaticcio, and Niccolo dell' Abbate, known as the First School of Fontainebleau, decorated the interiors of the new rooms. The artists became known as the School of Fontainebleau and their work had a major influence on Renaissance decoration throughout Europe. Their work included frescoes in elaborate stucco sculptural frames, cartouches in all forms, and medallions in high relief. The architecture was ornamented with sculpture of putti, of garlands of fruit, of satyrs and heroic figures from mythology. The most important works included twelve rectangular frescos, in highly decorative sculptured frames, in the Gallery of François I (1533–1539).[19]

Following the death of Francis I in 1547, his successor King Henry II continued to enlarge and embellish the chateau. The architects Philibert Delorme and Jean Bullant extended the east wing of the lower court, and decorated it with the first famous horseshoe-shaped staircase. In the oval court, they transformed the loggia planned by Francois into a Salle des Fétes or grand ballroom with a coffered ceiling. They designed a new building, the Pavillon des Poeles, to contain the new apartments of the King. The painters Primaticcio and Niccolò dell'Abbate continued their decoration of the new ballroom and the gallery of Ulysses with murals by Primaticcio framed in ornately sculptured stucco.[20]

Other châteaux of François I period

François I began other chateaux in the Paris region, The biggest and most impressive was the Château de Madrid, in what is now the Paris suburb of Neuilly, which he began in 1527, because he found the Louvre uncomfortable. It was largely abandoned and then demolished in the late 18th century. Another late château created by François I is the Château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The facade was entirely redone and, unlike the earlier châteaux, it was given an Italianate flat terrace roof lined with large stone vases with an emerging caved flame. Other notable châteaux of this period include the Château d'Ancy-le-Franc (1538–1546) in Burgundy.[21]

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, reconstructed by François I beginning in 1539

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, reconstructed by François I beginning in 1539 Decoration of the portal of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

Decoration of the portal of the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye_-_Madrid_front_facade.jpg.webp) Facade of the Château de Madrid, begun 1527, completed 1552, demolished 1792

Facade of the Château de Madrid, begun 1527, completed 1552, demolished 1792

Second period – Classical influence

Characteristics

The second period of French Renaissance architecture commenced in about 1540, late in the reign of François I, and continued until the death of his successor Henry II in 1559. This period is sometimes described as the high point of the style.[22] It included work by Italian architects including Giacomo Vignola and Sebastiano Serlio, but more and more it was made by French architects, particularly Philibert Delorme, Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau, Pierre Lescot and Jean Bullant, and by the sculptor Jean Goujon.[23]

The features of this period included the greater use of the ancient Classical orders of columns and pilasters, preceding from the most massive to the lightest. This meant starting at the bottom with the Doric order, then the Ionic, then the Corinthian on top. The order used on each level determined the style of that level of the facade. Philibert Delorme went further and added two new orders to his facades: French Doric and French Ionic. These columns were regular Doric and Ionic columns decorated with ornamental bands or rings.[23]

The second period featured also a wide variety of decorative plaques and sculptural decoration on the facades, usually borrowed from ancient Greek or Roman models. These included the caryatide, elaborate cartouches, renommées, relief statues representing Fame, over doorways, grotesques, often in the form of satyrs and griffons, and sculpted draperies and garlands. They also often included stylized monograms of the initials of the owner.[23]

Doorway design by Philibert Delorme

Doorway design by Philibert Delorme French Doric order column by Philibert Delorme

French Doric order column by Philibert Delorme Plan of the Fontaine des Innocents by Philibert Delorme (1547–1550)

Plan of the Fontaine des Innocents by Philibert Delorme (1547–1550) Stone reliefs of nymphs

Stone reliefs of nymphs

from the Fountain of the Innocents Drawings for Lescot Wing of the Louvre by Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau

Drawings for Lescot Wing of the Louvre by Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau Pan for Bulant Pavilion at the Tuileries Palace by Jean Bullant (1564)

Pan for Bulant Pavilion at the Tuileries Palace by Jean Bullant (1564) Bas relief by Jean Goujon, Hôtel de Sully, Paris

Bas relief by Jean Goujon, Hôtel de Sully, Paris

Château d'Anet (1547–1552)

The Château d'Anet was constructed by Philibert Delorme for Diane de Poitiers, the favorite mistress of Henry II, between 1547 and 1552. It originally had three wings, a chapel and a large garden, as well as an imposing gatehouse, whose centerpiece was the famous Nymph statue by Cellini, now at Fontainebleau, along with sculptures of a stag and two hunting dogs. The porch of the main facade was also a striking innovation; it was the first correct use in France of the three classical orders, one above the other. Only a few of the original buildings remain. The central building was later demolished, but the porch can be seen today in the courtyard of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. A third innovative feature was the chapel, consecrated in 1553. In his plan, Delorme combined the forms of the square, the Greek cross and the circle. The dome had a spiral coffered interior, resembling those in ancient Rome; it was one of the first of its kind in France.[24]

.jpg.webp) Engraving of the Château d'Anet, by Jacques-Androuet du Cerceau

Engraving of the Château d'Anet, by Jacques-Androuet du Cerceau Gatehouse of the Château d'Anet, with sculpture of stag and hunting dogs

Gatehouse of the Château d'Anet, with sculpture of stag and hunting dogs Portico of principal facade, showing the three classical orders (now at Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris)

Portico of principal facade, showing the three classical orders (now at Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris).jpg.webp) Inside of the spiral-coffered dome of the chapel

Inside of the spiral-coffered dome of the chapel

Château d'Écouen (1538–1550)

The Château d'Écouen, designed by Jean Bullant, features the classical orders on the portico on its western facade. it was inspired by the portico of the Pantheon in Rome. The columns of the facade rise all the way to the roofline. The interior is also remarkable, with some of the original ceramic tile floor still in place and highly decorated fireplaces. This chateau is now the French National Museum of the Renaissance.[21]

The Château d'Écouen (1538–1550), now the French National Museum of the Renaissance.

The Château d'Écouen (1538–1550), now the French National Museum of the Renaissance. Classical portico on the south facade of the Château d'Écouen (1538–1550)

Classical portico on the south facade of the Château d'Écouen (1538–1550)%252C_ch%C3%A2teau%252C_%C3%A9tage%252C_grande_salle_du_Roi_2.jpg.webp) Fireplace in the Grand Hall of the King, Château d'Écouen (1538–1550)

Fireplace in the Grand Hall of the King, Château d'Écouen (1538–1550) Ceramic floor tiles of Château d'Écouen (1538–1550)

Ceramic floor tiles of Château d'Écouen (1538–1550)

Lescot wing of the Louvre (1546–1553)

One of the last commissions of François I, given just a year before his death, was the reconstruction of a part of the Louvre Palace, built by Charles V, in order to make it more comfortable and palatial. The project was undertaken by Pierre Lescot, a nobleman and architect, and was modified by the new King, Henry II, who added a new pavilion on the southwest to serve as his residence. The result was a skillful blend of Italian and French elements. The facade featured arcades on the ground level in the Italian style, and was divided by three avant-corps decorated with sets of twin Corinthian columns and topped with consoles with rounded frontons. These vertical elements were balanced by the strong horizontal bands marking the floors, and by the gradual and subtle change of the ornament on each level, representing the three classical orders of architecture. [25] To avoid monotony, the frontons of the windows alternated between triangles and rounded arches. The top floor did not have a high roof lucarnes, like most other French Renaissance buildings; it was composed instead of alternating windows and sculptural decoration, beneath a new kind of roof, the called a comble brisé, which had two different angles of slope. It was crowned with a ridge of ornament.[26]

The sculptural decoration on the facade, by Jean Goujon was especially remarkable. On the two lower levels, it was discreet, composed of inlays of polychrome marble and medallions with sculpted garlands. However, on the attic or top floor, he lavishly covered every part of the wall with sculptures of slaves, warriors, trophies, and mythical divinities, representing in classical style the military triumphs of France.[25]

Inside the Lescot Wing the decoration was inspired by ancient Greece. In the ballroom, the balcony for the musicians was carried by caryatides made by Jean Goujon, inspired by those on the Acropolis in Athens. Goujon was also responsible for the coffered ceiling of the right stairway of the Lescot Wing, decorated with a sculpture of hunting scenes.[27]

_-_Louvre_west_wing_court_facade.jpg.webp) Lescot's facade as illustrated in Les plus excellents bâtiments de France (1576)

Lescot's facade as illustrated in Les plus excellents bâtiments de France (1576) West facade of the Lescot Wing

West facade of the Lescot Wing Caryatides supporting the musical tribune by Jean Goujon

Caryatides supporting the musical tribune by Jean Goujon Coffered ceiling of Henri II stairway of Lescot Wing

Coffered ceiling of Henri II stairway of Lescot Wing

Hôtel d'Assézat (1555–1556 and 1560-1562)

The hôtel d'Assézat in Toulouse, built by architect Nicolas Bachelier and, after his death in 1556, by his son Dominique, is an outstanding example of Renaissance palaces architecture of southern France, with an elaborate decoration of the cour d'honneur ("courtyard") influenced by Italian Mannerism and by classicism. As one of the first manifestations of the French classicism, its exceptionals ornementation and pristine condition earn it a mention in every overview of French Renaissance.[28]

Pierre Assézat, a wealthy woad merchant, launched the first phase of construction in 1555–1556. The main L-shaped structure was built along with the staircase pavilion in the corner. The designs of the façades, featuring twin columns which develop regularly over three floors (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian), take their inspiration from the great classical models such as the Coliseum. The capitals also precisely adhere to classical models, known from engravings. The erudite architecture—its source can also be traced to the treatises of the royal architect Sebastiano Serlio—expresses order and regularity.[28]

After Bachelier's death in 1556 the construction work stopped; it was restarted in 1560 under the direction of Dominique Bachelier, son of Nicolas. He undertook the creation of the loggia and the passageway, which divided up the courtyard, and the street gate. Much polychrome interplay (brick/stone) and various ornaments (cabochons, diamonds, masks) evoke luxury, surprise and abundance, themes peculiar to Mannerist architecture.[28]

Religious architecture

The Renaissance had less influence on French religious architecture; cathedrals and churches, for the most part, continued to be built or rebuilt in the Flamboyant Gothic style. However, a few classical elements introduced during the Renaissance appeared in churches. Examples include the classical portals of the churches of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois, directly across from the new Lescot Wing of the Louvre, and Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs in Paris. The latter was borrowed directly from the Palace of Tournelles, designed by Philibert Delorme. The church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont (1530–1552), near the Pantheon in Paris, has a Gothic choir, but a facade with a classical pediment, balustrades with classical columns a remarkable rood, or bridge, crossing the nave. [29]

The Church of Saint-Eustache, Paris (1532–1640), in the center of Paris, was begun by François I and is second in size only to Notre-Dame de Paris among Paris churches. It is a hybrid of Flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance styles. The exterior, plan and vaulted ceiling are Gothic, but the orders of classical columns and other Renaissance elements appear in the interior.[29]

One of the finest religious monuments of the French Renaissance is the tomb of François I and his wife Claude de France, located within the Basilica of Saint Denis (1547–1561). It was created by the architect Philibert Delorme and the sculptor Pierre Bontemps. The principal element is a triumphal arch, modeled after the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome, crowned with four statues of fame, as well as the King and Queen. The vault of the arch and the entablement are richly decorated with sculptural decoration of olive leaves and other classical themes, and with tablets of black and white marble. The tall, slender columns give the tomb an exceptional lightness and grace.[30]

.jpg.webp) Interior of Saint-Eustache, Paris

Interior of Saint-Eustache, Paris Rood screen of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont (1530–1545)

Rood screen of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont (1530–1545) Facade with classical orders of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont (1530–1552) in Paris

Facade with classical orders of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont (1530–1552) in Paris Tomb of François I and Claude of France (c. 1547–61)

Tomb of François I and Claude of France (c. 1547–61) South portal of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs (1559) in Paris

South portal of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs (1559) in Paris

Last projects

After the death of King Henry II, France was torn by the outbreak of the French Wars of Religion, which largely pushed aside architecture and design. Nonetheless, a few last Renaissance projects were launched, largely inspired by Catherine de Medici, the widow of Henry II.[31] The most important project of the period was the new Tuileries Palace. It was designed by the chief royal architect, Philibert Delorme, in response to the Queen's wish for a modern palace with a large park on what was then the edge of the city. It featured a central pavilion with low wings composed of arcades topped by a residential floor with alternating dormer windows triangular frontons. All the facades lavishly decorated in the Italian Renaissance style, including elongated sculpted figures inspired by the works of Michelangelo. After the death of Delorme in 1570, the task was taken up by Jean Bullant, but then it was interrupted again by the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre in 1572, and was not completed until decades later. The decorations invented by Delorme included a new style of classical columns, French Corinthian, banded with several ornamental rings.[31]

Catherine de Medici also imposed the Italian style at Fontainebleau, with the construction of a new wing, the Aile de la Belle Chiminée (wing of the beautiful chimney). The facade was designed by Francesco Primaticcio and featured a combination of Italian and French elements; pilasters, statues in niches, a high roof with lucarnes, a central frontispiece resembling Italian church architecture, and two diverging stairways.

The second plan of the Château de Verneuil (since demolished) by the young architect Salomon de Brosse (1576) was another landmark of the late French Renaissance style. It was commanded by Henry IV of France. Its symmetry, corner pavilions, twin pilasters, discreet roof, absence of lucarnes and its rotunda at the entrance made it a concise summary of the French Renaissance style at the end of the 16th century.[31]

Catherine de Medici also commissioned additions to the Château de Chenonceau. The bridge over the Cher river had been built by Philibert Delorme. After his death in 1570, Catherine asked Jean Bullant to built a picturesque gallery (1576) atop the bridge. A much larger ensemble of buildings around the bridge was planned by Bullant, but was never built.[32]

The Wing of the Belle Cheminée of the Château de Fontainebleau, by Francesco Primaticcio (1559–1600)

The Wing of the Belle Cheminée of the Château de Fontainebleau, by Francesco Primaticcio (1559–1600) Bridge of the Château de Chenonceau by Philibert Delorme and then Jean Bullant (1576)

Bridge of the Château de Chenonceau by Philibert Delorme and then Jean Bullant (1576)_-_Verneuil_bird's-eye_view_entrance_front_second_design.jpg.webp) Design for the Château de Verneuil by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1576)

Design for the Château de Verneuil by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1576) Facade design for garden wing of Tuileries Palace designed by Philibert Delorme

Facade design for garden wing of Tuileries Palace designed by Philibert Delorme The later plan of Jean Bullant for a pavilion of the Tuileries Palace

The later plan of Jean Bullant for a pavilion of the Tuileries Palace.jpg.webp) Fragment of Delorme's garden wing of the Tuileries Palace, now in the garden of the Palais de Chaillot

Fragment of Delorme's garden wing of the Tuileries Palace, now in the garden of the Palais de Chaillot

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Renaissance architecture in France. |

Citations

- Ducher 1988, p. 80.

- Mignon 2017, pp. 193–235.

- Ducher 1988, p. 80–92.

- "Le Val de Loire Siège du pouvoir Royal - Charles VII et Louis XI". UNESCO - Mission Val de Loire. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Mignon 2017, p. 199.

- Congrès archéologique 2003, p. 255.

- Mignon 2017, p. 201.

- Mignon 2017, p. 204.

- Mignon 2017, p. 204–215.

- Mignon, 2017 & pages-210-211.

- Ducher 1988, pp. 82–83.

- Mignon 2017, pp. 212–214.

- Ducher 1988, p. 84.

- Cropplestone, Trewin (1963). World Architecture. Hamlyn. p. 254

- Ducher 1977, p. 82.

- Mignon 2017, pp. 216–217.

- Mignon 2017, pp. 218–219.

- Mignon 2017, p. 219.

- Ducher 1988, pp. 86–88.

- Salmon, p. 9.

- Mignon 2017, pp. 218–224.

- Mignon 2017, p. 159.

- Ducher 1988, p. 88.

- Mignon 2017, p. 233.

- Ducher 1988, p. 90.

- Mignon 1917, p. 230.

- Mignon 1917, p. 231.

- Explanatory comments of Toulouse Renaissance exhibition (2018), Colin Debuiche.

- Texier 2012, pp. 24–25.

- Ducher 1988, p. 94.

- Mignon 2017, p. 234–235.

- Mignon 2017.

Bibliography

- Ducher, Robert (1988). Caractéristique des Styles (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-011539-1.

- Mignon, Olivier (2017). Architecture du Patrimoine Français - Châteaux de la Renaissance (in French). Éditions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2-7373-7611-5.

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2006). Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier (in French). Gisserot. ISBN 9-782877-474658.

- Salmon, Xavier (2011). Fontainebleau- Vrai demeure des rois, maison des siècles (in French). Versailles: Artlys. ISBN 978-2-85495-442-5.

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris - panorama de l'architecture de l'Antiquité à nos jours (in French). Paris: Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

- Litoux, Emmanuel (2003). Congrès Archéologique de France (in French). Paris: Société Française d'Archéologie.