Fumi-e

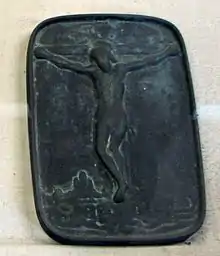

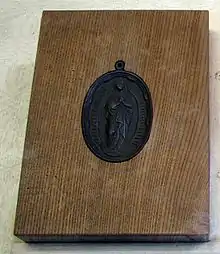

A fumi-e (踏み絵, fumi "stepping-on" + e "picture") was a likeness of Jesus or Mary onto which the religious authorities of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan required suspected Christians (Kirishitan) to step, in order to demonstrate that they were not members of that outlawed religion.[1]

History

The use of fumi-e began with the persecution of Christians in Nagasaki in 1629. Their use was officially abandoned when ports opened to foreigners on 13 April 1856, but some remained in use until Christian teaching was placed under formal protection during the Meiji period. The objects were also known as e-ita or ita-e,[2] while the forced test was called e-fumi.[2]

The Japanese government used fumi-e to reveal practicing Catholics and sympathizers.[3] Fumi-e were pictures of the Virgin Mary and Jesus. Government officials made suspected Christians trample on these pictures. People reluctant to step on the pictures were identified as Catholics and were sent to Nagasaki. The policy of the Edo government was to turn them from their faith, Catholicism; however, if the Catholics refused to change their religion, they were tortured. As many of them still refused to abandon the religion, they were killed by the government. Executions sometimes took place at Nagasaki's Mount Unzen, where some were boiled in the hot springs.[4]

Execution for Christianity was unofficially abandoned by the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1805.

Eighteenth-century Europe was aware enough of e-fumi for authors of fiction to mention it when alluding to Japan, as in Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726),[5] Oliver Goldsmith's The Citizen of the World (1760), and Voltaire's Candide (1759).[6] In modern Japanese literature, treading on the fumi-e is a pivotal plot element of the novel Silence[7][8] by Shūsaku Endō.

Many theologians have tried to contemplate the role of the fumi-e to Japanese Christians, some seeing the treading of the fumi-e as a sign of the love and forgiveness of Jesus Christ.[9]

Several secretly practicing Christianity did fumi-e and then maintained their beliefs secretly (Kakure Kirishitan); there were 20,000 secret Christians in Japan when Christianity was legalized again, down from 500,000 in Nagasaki during the height of Christian belief pre-fumi-e. University of Auckland professor Mark Mullins concluded that "In that sense, the [fumi-e] policies were effective."[10] Nagasaki Junshin Catholic University professor Simon Hill stated that if all of the fumi-e participants had instead chosen to be defiant and died, Christianity would not have continued in Japan; he stated "It is only because some made an existential decision to trample on the fumi-e, [...] that Christianity in Japan was able to survive."[10]

Form

Fumi-e were usually cast from bronze, but others were made of painted stone and some were woodblock prints. There are relatively few surviving fumi-e,[6] as most were simply thrown away or recycled for other uses. Some examples were displayed by the Smithsonian in their 2007 exhibition "Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th and 17th Centuries."[11][12]

See also

- Catholicism in Japan

- Kakure Kirishitan

- Ketman

- Martyrs of Japan

References

- Shunkichi Akimoto (1961). Exploring the Japanese Ways of Life. Tokyo News Service. p. 233. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

Attached to this word is an exotic, foreignized sort of interest though it was a native invention of the early Yedo Period and had remained a curious symbol of the anti-Christian policy of the Tokugawa feudalism.

- Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta (2004). Toward a Geography of Art. University of Chicago Press. p. 308. ISBN 9780226133119.

- Bradley K. Martin (19 December 1980). "Japanese Christian Group Keeps Relics of Old Faith in the Closet". Los Angeles Times. p. C1.

A government inquisition office devised a test called fumi-e...

- David E. Sanger (7 June 1991). "Volcano's Fury Turns a Shrine Into a Morgue". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Jonathan Swift (1726). "Part III. A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib, and Japan. Chapter 11". Gulliver's Travels.

To this I added another petition, that for the sake of my patron the king of Luggnagg, his majesty would condescend to excuse my performing the ceremony imposed on my countrymen, of trampling upon the crucifix: because I had been thrown into his kingdom by my misfortunes, without any intention of trading. When this latter petition was interpreted to the Emperor, he seemed a little surprised; and said, he ... suspected I must be a Christian...

- Michael North (2010). Michael North (ed.). Artistic and Cultural Exchanges Between Europe and Asia, 1400–1900: Rethinking Markets, Workshops and Collections. Ashgate Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 9780754669371. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- William T. Cavanaugh (1998). "The god of silence: Shusaku Endo's reading of the Passion". Commonweal. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- Jeff Keuss (March 2007). "The Lenten Face of Christ in Shusaku Endo's Silence and Life of Jesus". Expository Times. 118 (6): 273–279. doi:10.1177/0014524606076087. S2CID 170461263. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- e.g. Masao Takenaka: When the Bamboo Bends, Christ and Culture in Japan, WCC 2002 pgs 50-51

- Tan, Yvette (24 November 2019). "The Japanese Christians forced to trample on Christ". BBC. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Jenkins, Mark (20 July 2007). "Portugal's Unending Sphere of Influence". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- Michael Fragoso (11 July 2007). "Fair Trade with 17th-Century Portugal". The American. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.