Gender diversity

Gender diversity is equitable or fair representation of people of different genders. It most commonly refers to an equitable ratio of men and women, but may also include people of non-binary genders.[1] Gender diversity on corporate boards has been widely discussed,[2][3][4] and many ongoing initiatives study and promote gender diversity in fields traditionally dominated by men, including computing, engineering, medicine, and science It is argued that some proposed explanations are without merit and are in fact dangerous, while others do play a part in a complex interaction of factors. It is suggested that the very nature of science may contribute to the removal of women from the ‘pipeline’.[5]

Benefits of gender diversity

Companies are more likely to attract more diverse people,[6] and people who consider gender equality policies when considering different employers.[7]

Financial performance

Some studies show that higher diversity in the workforce is expected to bring higher returns, but other studies fails to support this claim.[8]

Reputation

Gender diversity in companies leads to improved reputation both directly and indirectly. Directly because it's demonstrated that companies with a higher percentage of women board directors are favorably viewed in sectors that operate close to the final customers and are more likely to be on Ethisphere Institute's list of the “World's Most Ethical Companies".

Indirectly, women directors are more likely to notice and less likely to commit fraud. Moreover, gender diversity policies seem also to be correlated with increased CSR, as well as having better overall organizational image.[9][10]

Customer base

Since men and women have different viewpoints, ideas, and market insights, a gender-diverse workforce enables better problem solving. A study done in 2014 by Gallup finds that hiring a gender-diverse workforce allows the company to serve an increasingly diverse customer base. This happens because a gender-diverse workforce eases the process of accessing resources, such as multiple sources of information or credit, and industry knowledge.[11] Gender diverse organizations were also shown to benefit from increased customer understanding and satisfaction.[12]

Decision making processes

Gender diversity in boards increases diversity of ideas by introducing different perspectives and problem-solving approaches. This gives teams increased optionality and decision-making advantages.[13]

Diversity of management styles

A recent survey by RSA found that women are considered to "bring empathy and intuition to leadership", since they have greater awareness of the motivations and concerns of other people. 62 per cent of the respondents of the survey said women contribute differently in the boardroom than their male colleagues. A similar proportion saw women as more empathetic, with a better insight into how decisions play out in the wider organization. When it came to communications and effective collaboration, “over half felt that women were better”.[14][15] Gender-diverse organisations also enjoy heightened levels of creativity, innovation and problem-solving.[16][17][18] Besides, the results of an study in this topic showed that there's a small difference in attendance when the director is a woman. In mentioned study, it was registered that in 74 firms there were problems with attendance, in which 3.4% were male directors and 3.2% were women. Although it's a 0.02% difference, it was shown that out of 84 directors 7 were women. [19]

Measuring gender diversity

In the boardroom

Between Spring 2014 and Spring 2015 there was an increase in the number of female Chairs within the FTSE 100 reports.[20] Spring 2014 saw 1 female chair in the FTSE, this increased to 3 by Spring 2015. The number of Female CEOs in the FTSE 100 also rose between 2014 and 2015. In Spring 2014 the report showed there were 4 female CEOs in the FTSE 100, this increase to 5 by Spring 2015. By 2017, the number of female CEOs among Fortune 500 companies numbered 32 (~6%).[21] Female CFOs in the FTSE 100 saw the highest increase. In Spring 2014 there were 8 female CFOs in the FTSE 100, this rose to 12 by Spring 2015.

In financial markets

As of 2016, State Street Global Advisors offers an exchange traded fund (ETF) that tracks companies with relatively high proportions of women in executive and director positions.[22] The ETF follows an index of 185 publicly traded US companies with gender-diverse executive leadership, defined as Senior VP or higher.[22][23] Each company in the index must include at least one woman on its board or as CEO.[23] The fund trades under the symbol SHE and has risen 4.96% in value in its first nine months since inception.[23] In support of addressing systemic gender bias against women in leadership and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) that manifests early in life, the ETF provider has pledged to direct an unknown portion of its revenue to charitable organizations.[24]

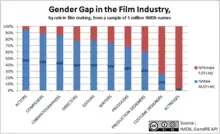

In the film industry

The analysis of The Internet Movie Database (IMDb, 2005 data dump) shows how wide the gender gap is in the film industry, especially for the most prestigious types of jobs. There are nearly twice as many actors as actresses in IMDB. Prestigious jobs such as composer, cinematographer, director are respectively 88%, 76%, and 86% male-dominated.[25]

In the life sciences industry

The life sciences industry covers a lot of ground and includes pharmaceutical companies, research support and services firms, research tool and reagent manufacturers, among other types, though in some contexts it is equated with drug development companies (Big Pharma and small pharma). According to a pair of 2017 industry reports, men and women enter the industry in equal numbers, but women comprise ¼ or less of C-suite positions, and less than 20% of Board of Directors positions.[26] [27] The first female CEO of a large pharmaceutical company emerged in 2017—Emma Walmsley at GlaxoSmithKline—which translates to 1% of Big Pharma CEOs being women.[26]

See also

References

- Sharon E. Sytsma (2 February 2006). Ethics and Intersex. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-1-4020-4313-0.

- Taylor, Kate (26 June 2012). The New Case for Women on Corporate Boards: New Perspectives, Increased Profits, Forbes

- Campbell, Kevin & Antonio Minquez-Vera. Gender Diversity in the Boardroom and Firm Financial Performance, Journal of Business Ethics (2008) 83:435-451

- Clark, Nicola (27 January 2012). Getting Women Into Boardrooms, by Law, The New York Times

- Blickenstaff, Jacob Clark (2005). "Women and science careers: leaky pipeline or gender filter?". Gender and Education. 17 (4): 369–386. doi:10.1080/09540250500145072.

- Rau, Barbara L.; Maryanne, Hyland (2003). "Corporate Teamwork and Diversity Statements in College Recruitment Brochures: Effects on Attraction". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 33 (12): 2465–2492. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb02776.x.

- "Gender Diversity in Management: targeting untapped talent". Australian Institute of Management. 2012.

- Eagly, Alice H. "When good intentions aren't supported by social science evidence: diversity research and policy". The Conversation.

- "Why diversity matters". Catalyst Information Center. 2013.

- Witt, Peter; Rode, Verena (2005). "Corporate brand building in start-ups". Journal of Enterprising Culture. 13 (3): 273–294. doi:10.1142/S0218495805000173.

- S. B. Badal (2014). "The business Benefits of Gender Diversity". Gallup Business Journal.

- Herring, Cedric (2009). "Does diversity pay?: Race, gender, and the business case for diversity". Sociological Review. 74 (2).

- A. A. Dhir (2015). "Challenging Boardroom Homogeneity: Corporate Law, Governance, and Diversity". Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation.

- D. Medland (2012). "Women and the Workplace: The benefits of gender diversity put to the test". Financial Times.

- "Gender, Diversity, Leadership & Communication in Organizations". Juan F Ramirez Ferrer. 2015.

- Campbell, Kevin; Minguez-Vera, Antonio (2008). "Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance". Journal of Business Ethics. 83 (3): 435–451. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9630-y.

- Østergaard, Christian R.; Timmermans, Bram; Kristinsson, Kari (2011). "Does a different view create something new? The effect of employee diversity on innovation" (PDF). Research Policy. 40 (3): 500–509. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2010.11.004.

- Dezsö, Cristian L.; Ross, David Gaddis (2012). "Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation". Strategic Management Journal. 33 (9): 1072–1089. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.8626. doi:10.1002/smj.1955.

- Adams, Renee B.; Ferreira, Daniel (2004). "Gender Diversity in the Boardroom". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.594506. ISSN 1556-5068.

- "Home". 10 October 2016.

- Wright, Rob (12 February 2018). "Gender Diversity In Leadership - How Does Biopharma Compare?". Life Science Leader (Blog). Editor's Blog. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- "SHE: The SPDR® SSGA Gender Diversity Index ETF" (PDF). spdrs.com. State Street Global Advisors.

- "Market-Cap Weighted Gender Diversity Index Fund". ETF.com.

- "Better Together: Introducing the SPDR SSGA Gender Diversity Index ETF (SHE)" (PDF) (PDF). 2016.

- NCYW (May 2014). GendRE & IMDb: An Open Data Analysis of The Film Industry Gender Gap, http://nocountryforyoungwomen.com/

- Rey, Camille Mojica (3 September 2018). "Why And How To Close The Gender Gap In The Life Sciences". Life Science Leader.

- "Gender Diversity in STEM: The State of Pharmaceutical Leadership". Doctor4U. Retrieved 28 November 2019.