Gender roles in Mesoamerica

Gender roles in Mesoamerica were complementary in nature, meaning that men and women had separate but equally important roles in society.[1] Evidence also suggests the existence of gender ambiguity and fluidity in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican societies.[2] Gender relations and roles also varied among different Mesoamerican cultures and societies, through time, and depending on social status.[1] Mesoamerica or Meso-America (Spanish: Mesoamérica) is a region and culture area in the Americas, extending approximately from central Mexico to Honduras and Nicaragua, within which a number of pre-Columbian societies flourished before the Spanish colonization of the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Boys, for example, are given toys to play with that establish their future mascpresenting their future economic roles.[3] The stereotype that women play a minimal role in the family is far from accurate. Although women's roles in agriculture have been underestimated, if it were not for the contributions of women in agriculture, the family would not survive.[3]

With the arrival of the Spanish and their subsequent colonial rule starting in the 16th century, Mesoamerican gender relations could no longer be considered distinct cultural practices.[4] Gender roles and gender relations instead became subject to the practices of Spanish colonial rule and the casta system which racially categorized the Mesoamericans and their indigenous and mixed descendants.[5] However, despite suppression by Spanish colonialization, aspects of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican gender roles have survived in indigenous communities to this day.[6]

Roles

Labor

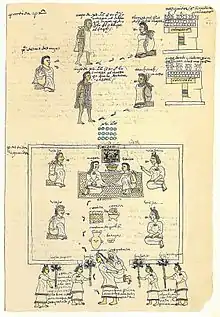

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican arts contains evidence of a gendered division of labor, depicting women engaged in domestic labor such as weaving, childrearing, tending to animals, and giving birth. Weaving was more strongly associated with gender for the Classic Mexica than the Classic Maya, for which it indicated class.[7] Men were depicted with weapons and in positions of religious and political authority. While evidence suggests that farming was seen as a male activity, the gendered divisions of labor may not have been so strict. Analysis of the bones of women revealed evidence of wear patterns strongly associated with the repetitive motion of grinding maize, suggesting women were primarily engaged in that labor.[8] Anthropologists such as Miranda Stockett believe it is likely that men, women, and children all participated in farming and domestic labor to varying degrees.[2]

Women also hold a variety of roles within the family. These range from harvesting the grains and preparing the food for the family, to taking care of the domesticated animals. When examining the role women play in planting and harvesting, one notices that this area still holds some stereotypes with how the women aid their husbands. In some societies women are responsible for sowing and harvesting the crops but are restricted from ploughing. The roles shared between men and women in agriculture in Santa Rosa, Yucatán. Although women are allocated such tasks as sowing, with all its association with fertility, they are rigidly excluded from ploughing.[9] The significance of not allowing women to plough is related to human reproduction. The common belief is that women should not be able to plough because it invades on the male’s role in human reproduction. Thus, men are able to carry out all stages of the agriculture cycle, including the planting of the seed, while women—even in their role as head of the household—are sanctioned to rely upon men for particular tasks.[9] The reasoning behind limiting women’s roles with production of the crops is directly related to reproduction. Women rely on men for some tasks when planting crops, just as women need the assistance of the men in reproduction.

Aside from producing food, another important task that women carry out is food preparation, which demands the most attention because the women must sit by the hearth for long periods of time. In the role women have in the preparation of maize, after the grains have been harvested, the next step is to process them so the family can consume them. Apart from childbearing and childrearing, one of the women’s foremost duties was the processing of dried corn into maize flour. After being boiled with lime, softened maize kernels were ground with a tubular hand stone on a flat grinding stone (metate) into maize dough.[10] Once the dough is formed, a variety of food items can be made. Here the metate plays an important role in the processing of maize, the staple crop of the culture.

The last major role women hold in a society relates to animals. Many households have corrals for their domestic animals, and this is another area that women are responsible for. When discussing the roles women play with domestic animals the corral is very important to the women of the household and is another area where they spend a great deal of their time. Here she spent a good part of her time, taking care of the animals…caring for the chickens, cleaning the dovecote, feeding the mule, rabbits…here in the corral one eats from one’s work.[11]

Women play an important role in the survival of their families because the family survives from the work they perform in the corral.

Additionally, the success of Mesoamerican rituals was dependent on the production of food and textiles, to which women contributed much labor. These rituals were vital to ensuring good relationships with not only the gods but also within communities. In Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, Diego de Landa observed that for nearly all rituals, Mayan women were responsible for preparing food for both offerings and consumption in addition to cloth as offerings.[1]

Gender relations among the Mexica also suggested gender complementarity. For example, dying in battle and dying in childbirth elevated men and women respectively. In childbirth, women confront the goddess Cihuacoatl, and if they died, their bodies were considered temporarily imbued with the power of the goddess. Since parts of their bodies could be used as a protective amulet or to curse others, the husband kept vigil by her body for four nights.[12]

Politics

Some Mesoamerican women were able to assume roles as political leaders, such as women in Maya society, others such as women in Mexica society were not.[8] However while Mexica women couldn't serve in this capacity, they were given equal legal and economy rights and noble Mexica women could become priestesses.[6] Additionally, two influential political figures headed the highest levels of Mexica government. One was the tlatoani, literally "the one who speaks", and another was the cihuacoatl, literally "woman snake", both representing a male/female pair. The tlatoani was responsible for military affairs and the cihuacoatl was responsible for domestic affairs like the food supply and administering justice. The position of cihuacoatl was in reality occupied by a man, but the associations with femininity were significant enough that the cihuacoatl, of the same name as the goddess, wore women's dress for ceremonies.[12] As Mesoamerican states became more centralized over time, men's power became more associated with their control over women and their capacity for productive and reproductive labor. As a result, opportunities available to women were gradually limited.[13] In the case of the Mexica, military concerns may have eclipsed women's public significance.[12]

Gender ambiguity

Although pre-Columbian Mesoamerican art contained depictions of the body as male or female as represented by genitalia or secondary sex characteristics, it also included representations of bodies with exposed chests and waists but no visible sexual characteristics. Depictions of rituals conducted by elite Mesoamericans have included women dressed in the traditional costume of men and men dressed in the traditional costume of women.[2] Classic Maya text also includes situations where gender is not linguistically marked or where gender is marked linguistically as male for a speaker who appears to be a woman or vice versa.[13] This evidence suggests considerable fluidity between the genders in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican society.

Notes

- White, Christine D. (2005-10-01). "Gendered food behaviour among the Maya: Time, place, status and ritual". Journal of Social Archaeology. 5 (3): 356–382. doi:10.1177/1469605305057572. ISSN 1469-6053.

- Stockett, Miranda K. (2005-12-01). "On the importance of difference: re-envisioning sex and gender in ancient Mesoamerica". World Archaeology. 37 (4): 566–578. doi:10.1080/00438240500404375. ISSN 0043-8243.

- Chassen-Lopez, Francie R.; Heather Fowler-Salamini; Mary Kay Vaughan (1994). Cheaper Than Machines Women of the Mexican Countryside. The University of Arizona Press. pp. 27–30.

- The legacy of Mesoamerica : history and culture of a Native American civilization. Carmack, Robert M., 1934-, Gasco, Janine., Gossen, Gary H. (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson/Prentice Hall. 2007. ISBN 9780130492920. OCLC 71833382.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Howard), Jackson, Robert H. (Robert (1999). Race, caste, and status : Indians in colonial Spanish America (1st ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826321084. OCLC 39890515.

- "Gender and Religion: Gender and Mesoamerican Religions - Dictionary definition of Gender and Religion: Gender and Mesoamerican Religions | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

- McCAA, Robert (May 2003). "The Nahua calli of ancient Mexico: household, family, and gender". Continuity and Change. 18 (1): 23–48. doi:10.1017/s026841600300448x. ISSN 1469-218X.

- Plumer, Hannah (October 2011). "Gender in Mesoamerica: Interpreting Gender Roles in Classic Maya Society". The Collegiate Journal of Anthropology. Archived from the original on 2018-09-16.

- Sage, Colin; Janet Henshall Momsen; Vivian Kinnaird (1993). Deconstructing the Household Different Places, Different Voices. Routledge. pp. 243–46.

- Stone, Andrea J.; Bella Vivante (1999). Women in Ancient Mesoamerica Women's Role in Ancient Civilizations. Greenwood Press. pp. 293–300.

- Goldsmith, Raquel Rubio; Heather Fowler-Salamini; Mary Kay Vaughan (1994). Seasons, Seeds and Souls Women of the Mexican Countryside. The University of Arizona Press. pp. 140–45.

- 1978-, Dodds Pennock, Caroline (2008). Bonds of blood : gender, lifecycle and sacrifice in Aztec culture. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire [England]: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230003309. OCLC 156831786.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- 1956-, Joyce, Rosemary A. (2000). Gender and power in Prehispanic Mesoamerica (First ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292740648. OCLC 608820583.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

- Rosenbaum, Brenda; Christine Eber (2007). "Women and gender in Mesoamerica". In Robert M. Carmack; Janine Gasco; Gary H. Gossen (eds.). The Legacy of Mesoamerica: History and Culture of a Native American Civilization. Exploring Cultures series (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/PrenticeHall. ISBN 978-0-13-049292-0. OCLC 71833382.

- Tway, Maria B. (2004). "Gender, Context, and Figurine Use: Ceramic Images from the Formative Period San Andres Site, Tabasco, Mexico" (unpublished Master's thesis). Tallahassee: Dept. of Anthropology, Florida State University. Archived from the original on 2010-11-19. Retrieved 2009-08-21.