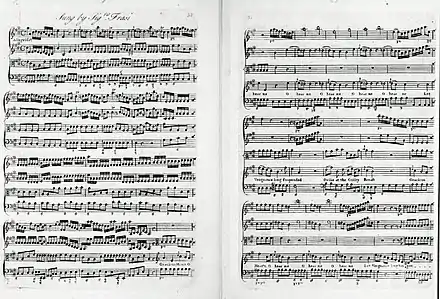

Giulia Frasi

Giulia Frasi (also Frassi[1][2]), was born c. 1730 and died in 1772[3] or after May 1774.[4] She was an Italian soprano who was primarily active in London. She sang in every one of Handel's English oratorios (with the exception of Semele), including various world premières for which the composer wrote roles specifically for her.[2][5]

Early life and career

Italy

There is very little biographical information about Giulia Frasi. She was born in or around Milan before 1730. She had a younger brother named Giovanni who, like her, settled in England and died there in 1795 at 65, after having worked extensively as a tailor-embroiderer for the Prince of Wales.[3]

In her native Italy Frasi studied singing with Milanese composer Giuseppe Ferdinando Brivio. She also performed there for a few years during the early 1740s[3] making her operatic debut at Lodi (1740) and then singing in Alessandria (1740), Bergamo (1741), and Modena (1742).[2][4]

London

She moved to London in autumn 1742 – perhaps following Giuseppe Ferdinando Brivio – with her friend and fellow singer the contralto Caterina Galli.[3] In England she joined Lord Middlesex's Italian opera company.[4] Lord Middlesex was director of Italian opera at the Haymarket Theatre whose purpose was to challenge Handel's solid hold on London opera goers. She studied under the English educator, musician and historian Charles Burney.[3]

Her English career began shortly after her arrival, first performing in comprimario roles at the King's Theatre. Her profile rising gradually within the company, she soon appears in secondary roles, including breeches roles (for example: Taxiles (1743) and Cleon (1747–8), both in Rossane, and the giant Briareus in the première of Gluck's La caduta de' giganti in 1746).[5][3]

Her actual London début took place on 2 November 1742 at the King's Theatre as Mahobeth in the pasticcio Gianguir with music by Giovanni Battista Lampugnani, Johann Adolph Hasse and Giuseppe Ferdinando Brivio. The latter's music will also be used in two other pasticcios produced at the King's Theatre during the 1740s: Mandane, premièred on 12 December 1742 (and later, L'incostanza delusa, premièred on 9 February 1745).

This was followed straight away by a period of intense artistic activity on the London stage, still at the King's Theater, singing works by Giovanni Battista Lampugnani, Johann Adolph Hasse, Nicola Porpora, Baldassare Galuppi.[3][2]

However, just a couple of years after her arrival in the British capital, shortly after the première of the pasticcio L'incostanza delusa, all theatres in London were closed because of the political turmoil caused by the Stuart rising. When the political situation improved theatrical activities recommenced with a première of Christoph Willibald Gluck's opera La caduta de' giganti (The Fall of the Giants) on 17 January 1746. La caduta de' giganti, a command from Lord Middlesex, with a libretto by Vanneschi, glorified the hero of the battle of Culloden, the Duke of Cumberland.[7] Frasi, who had created the role of the giant Briareo for Gluck, was back on stage and continued her intense musical activity: first with a role in Gluck's second London opera (Artamene)[6] and then with works by Matteo Capranica, Antonio Caldara, Francesco Maria Veracini, Domènec Terradellas, Pietro Domenico Paradisi and others.[3][2]

In addition, her association with the annual charity concerts in aid of the Fund for Decay'd - known today as the Royal Society of Musicians - started as early as 1743. The earliest documented occasion (a fundraiser event) on which she performed English-language airs, including some by Handel, in public was as early as March 1746.[4] Her charity fundraising also included benefactors such as the Foundling Hospital, where Handel held regular benefit concerts and annual performances of Messiah[8] that continued until Handel's death and beyond,[9] the Jermyn Lying-in Hospital, in aid of which she sang in a performance of Arne's revised version of Alfred organised at the King's Theatre on 12 May 1753,[4] and many others.

Noticed by Handel

A few years after her London début she is noticed by Handel, who, appreciating her singing,[3] her determination to sing articulately in English and, above all, her musical expressiveness,[4] hires her for his 1749 season.[3]

That same year she becomes his principal soprano and sings the title role in Susanna (her first Handel oratorio).[2] Handel takes her under his wing and she quickly becomes one of his favourites. "The subtle artistry and emotional depth of Handel's [powerful] writing for Frasi"[4] is a testament to how expressive her singing must have been and to how much Handel must have estimated this particular talent of hers.

For example, in Theodora (premièred in 1750 with Frasi being once again the principal soprano in a title role written specifically for her by Handel), Act II, Scene 2 opens with "a plaintive symphony for flutes and strings establish[ing] the lonely despair of the character, and [then] her dread for the violation of her chastity is sublimely expressed in 'With Darkness deep as is my Woe' – in the extraordinary key of F sharp minor; [...with] pathos-generating rolling strings and almost unbearable uses of silence between phrases. After an interlude of 'soft Musick' the desperate woman prays effusively for divine deliverance in 'O that I on Wings cou'd rise'."[4]

1749, a busy year[4][3]

Some of Giulia Frasi's engagements during the year 1749:

- Twice weekly: noon concerts at Ranelagh with the tenor John Beard.

- revival of Handel's Messiah.

- revival of Handel's Hercules.

- 10 February: production of Handel's Susanna (including première and creation of the role of Susanna).

- 17 March: production of Handel's Solomon (including première and creation of the principal soprano roles).

- 6 April: puts on her own benefit concert at the New Theatre.

- 10 April: concert for the benefit of the five-year-old singer Cassandra Frederick, with whom Frasi may later have starred in the première of Handel's The Triumph of Time and Truth (1757) and the revivals of Handel's oratorios Belshazzar (1758), Jephtha (1758), Messiah (1758), Judas Maccabaeus (1759), and Thomas Arne's The Masque of Alfred (1759).[10]

- 13 April: benefit concert for her friend and colleague Caterina Galli.

- 24 April: Mr Tozzi's concert at Hickford's Room.

Private life

Addresses in London

.jpg.webp)

From 1745 to 1752 Giulia lived in Great Pulteney street, not far from Golden Square.[3] Great Pulteney Street had just been laid out during the area's redevelopment in the early eighteenth century (Many of the houses built at this time still survive today). The street was never fashionable though, nor was it identified with any trade or craft. Yet there was a large brewery and there were famous musical instrument makers as well: notably Kirkman's, which had been established there in 1739 and remained until 1750, and, from 1742 to 1774, the harpsichord-maker Burkat Shudi, founder of the firm now known as Broadwood & Sons. Composer Michael Festing also lived there between 1747 and 1752.[11]

Then she moved to Gerrard street,[3] which is now part of London's Chinatown. She lived there at Charles Churchill's (Horace Walpole's future brother-in-law) for many years with her daughter (born in 1743).[3] At the time, the City of Westminster had its Penny Post offices at number 39. In 1740, No. 44 had become an apothecary's shop and was occupied until 1765 by the apothecary to George III's household. Many artists lived in Gerrard Street, for instance: the painter Chevalier Andrea Casali, or the architect John Crunden. The tavern at number 9 was the first home of The Club, founded in 1764 by Joshua Reynolds and Dr. Samuel Johnson.[12]

Wages

She was paid 6 guineas, very high wages at the time, for the charity revivals of Handel's Solomon at the Foundling Hospital in 1754, 1758 and 1759. She was the highest paid singer at Handel's Foundling Hospital performances of Messiah.[3][2]

Voice

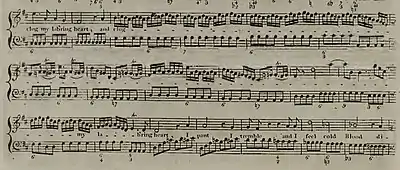

Giulia Frasi was endowed with a beautiful and robust soprano voice whose expressive qualities were greatly valued by Handel, much more than her technical ones. Indeed, allegedly, Giulia had a very limited interest in studying and practicing;[3] Burney tells us an anecdote showing the composer's sarcasm about Giulia's motivation regarding training: "When Frasi told him, that she should study hard; and was going to learn Thorough-Base, in order to accompany herself: Handel, who well knew how little this pleasing singer was addicted to application and diligence, says, 'Oh – vaat may we not expect!' "[4] Nonetheless she did study under Handel[3][13][2] - along with Caterina Galli - and benefited greatly from his tuition.[2]

In his General History of Music (1789), Charles Burney remembers her at the beginning of her career as "[being...] young, and interesting in person, with a sweet and clear voice, and a smooth and chaste style of singing, which, though, cold and unimpassioned, pleased natural ears, and escaped the censure of critics."[3][4]

She had excellent reviews, especially in Salisbury, and was highly appreciated by the British public,[5][2] whose preference yet was the nightingale singing of castrati rather than a voice whose abilities had nothing exceptional however delicate it was.[1][2]Although it is to be noted that she did reprise some castrati roles in revivals (for example in Artaxerxes) and that arias written specifically for her do occasionally include fiery - if short - coloraturas. "Gracious Heav'n, O hear me!" composed by Arne for Frasi and added to The Masque of Alfred is a "lively da capo aria di bravura."[4] "Là per l'ombrosa sponda!", found in Vincenzo Ciampi's Trionfo di Camilla is another example of virtuoso aria written for Frasi. Both arias are strongly influenced by the Neapolitan school, whose composers Frasi had sung earlier in her career. Burney also recorded that a virtuoso aria by Pergolesi "was sung at concerts by Frasi for ten years, at least."[4]

However, inspired by her rare and particular talent in musical expressiveness, Handel composed for her music of overwhelming sensitivity and beauty.[1] "Time and time again [you] feel [yourself] drawn to the empathetic temperament and lyrical ease of the vocal writing, embodied in the music Handel wrote for her."[14] Her roles contain vivid scenes of emotional and spiritual drama; they depict suffering and distress along with courage, dignity, and selflessness,[4] a whole palette of subtle and complex human emotions. The wonderful series of oratorio parts Handel composed for her, including the two Queens in Solomon, the title roles in Susanna and Theodora, and Iphis in Jephtha, are an indication of his regard for her expressive powers, though they are not technically arduous; their extreme compass is B3 to A5.[2]

Following in Handel's steps, Smith's Paradise Lost required Frasi to express innocence, culpability, pious sorrow and penitence when Eve faces the consequences of her new and inevitable mortality.[4] The aria "It comes" is a showcase of Smith's and Frasi's abilities in conveying such emotions. Rebecca is another example of Smith showcasing Frasi's talent at expressing human feelings in music.

On a different note, Burney highlights that "having come to this country at an early period of her life, she pronounced our language in singing in a more articulate and intelligible manner than the natives[.]"[3][4]

Repertoire[3][1]

Note that the table below is not exhaustive. Note also that the works/events listed in bold are documented, the ones not in bold are plausible suppositions.

| Year | Work | Role | Composer | Première or Revival | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1740 | La Constanza in trionfo[2] | ? | Giuseppe Ferdinando Brivio | Lodi, Italy | |

| 1740 | Il Bajazet[2] | ? | Giovanni Colombri | Alessandria, Italy | |

| 1742 | Tito vespasiano o La clemenza di Tito[2] | ? | Johann Adolph Hasse | revival | Modena, Italy |

| 1742 | Gianguir | Mahobeth | Giovanni Battista Lampugnani, Giuseppe Ferdinando Brivio and Johann Adolph Hasse | première | pasticcio |

| 1742 | Mandane | Emira | Giuseppe Ferdinando Brivio | première | pasticcio |

| 1743 | Enrico | ? | Baldassare Galuppi | première | at the King's Theater. |

| 1743 | Temistocle | Roxana | Nicola Porpora | revival or new version première (?) | at the Haymarket Theatre |

| 1743 | Rossane o Alessandro Nelle Indie | Tassile | George Frideric Handel and Giovanni Battista Lampugnani | première | pasticcio: In 1743 Lampugnani took the place of Baldassarre Galuppi as musical director of the King's Theater. On 15 November of the same year he produced Rossane, a rearrangement of Handel's Alessandro. |

| 1744 | Alfonso e Alceste | Garzia | Giovanni Battista Lampugnani | première | at the King's Theater. |

| 1745 | L'incostanza delusa | ? | Giuseppe Ferdinando Brivio | première | pasticcio, at the King's Theater. |

| 1746 | Alessandro nell'Indie | Timagene | Giovanni Battista Lampugnani | revival of the pasticcio of 1743 (?) | at the King's Theater. |

| 1746 | 'La caduta de' giganti | Briareo | Christoph Willibald Gluck | première | In 1745 Lampugnani had to return to Italy, and he was replaced by Christoph Willibald Gluck who accepted the post at the musical director of the King's Theatre upon an invitation from Lord Middlesex.The opera consists largely of music from Gluck's earlier works, lack of time having forced him to this device. The opera did not meet with success.[7] |

| 1746 | Artemene[6] | ? | Christoph Willibald Gluck | première | The opera also consists largely of music from Gluck's earlier works, lack of time having forced him to this device. The opera did not meet with success either.[7] |

| 1747 | Rossane o Alessandro Nelle Indie | Cleon | George Frideric Handel and Giovanni Battista Lampugnani | revival | pasticcio: In 1743 Lampugnani took the place of Baldassarre Galuppi as musical director of the King's Theater. On 15 November of the same year he produced Rossane, a rearrangement of Handel's Alessandro. |

| 1747 | La maestra (?) | ? | Gioacchino Cocchi | revival | |

| 1747 | Lucio Vero[2] | ? | George Frideric Handel | revival (?) | pasticcio opera containing music by Handel and performed by the "Middlesex" opera company (named after Lord Middlesex) |

| 1748 | Judas Maccabaeus[4] | Israelite woman | George Frideric Handel | revival | David Vickers explains that "when Handel needed to recruit a new principal soprano soloist for his revival of Judas Maccabaeus (4 March 1748), Frasi managed to squeeze in her fully fledged English oratorio debut for him between performances of a revival of Galuppi's Enrico."[4] |

| 1748 | Enrico[4] | ? | Baldassare Galuppi | revival | at the King's Theater. |

| 1749 | Susanna | Susanna | George Frideric Handel | première | at Covent Garden |

| 1749 | Hercules | Iole | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1749 | Solomon | triple part of the two queens and the first prostitute | George Frideric Handel | première | at Covent Garden with the contralto Caterina Galli, the bass Henry Theodor Reinhold and the tenor Thomas Lowe |

| 1749 | La maestra (?) | Gioacchino Cocchi | revival | ||

| 1749 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at Covent Garden with Caterina Galli[9] |

| 1750 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | with Caterina Galli and Gaetano Guadagni. (Handel composed new versions of "But who may abide" and "Thou art gone up on high" for Guadagni).[9] |

| 1750 | Alceste (?) | Calliope (?) | George Frideric Handel | n/a | This was rehearsed but eventually abandoned. Handel re-used the music in oratorios.[15] It is plausible that Frasi was part of the cast as, by then, she was already Handel's favourite principal soprano. Moreover, Calliope's ode to sleep ("Gentle Morpheus") shows typical hallmarks of other "Handel/Frasi collaborations". |

| 1750 | Saul | Michal | George Frideric Handel | revival | at Covent Garden |

| 1750 | Theodora | Theodora | George Frideric Handel | première | at Covent Garden premiere, with Gaetano Guadagni. |

| 1750 | 'Adriano in Siria | Emirena | Vincenzo Legrenzo Ciampi | revival but première of the aria "Oh Dio! Mancar mi sento" | at the King's Theatre, with the famous castrato Gaetano Guadagni and the tenor Filippo Laschi. For Frasi Ciampi wrote the emotional aria "Oh Dio! Mancar mi sento" and added it to Act III, Scene 7 of the London version.[4] The opera ran for eight performances, concurrently with Handel's Theodora[4] |

| 1750 | La Serva Padrona | Serpina | Giovanni Battista Pergolesi | revival | |

| 1750 | Il Trionfo di Camilla | Camilla | Vincenzo Legrenzo Ciampi | première | at the King's Theatre. The opera was a failure and had only two performances.[4] |

| 1751 | Belshazzar | Nitocris | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1751 | Alexander's Feast | ? | George Frideric Handel | revival | The choice of Hercules and Alexander's feast were interpreted the same evening (1 March 1751) with great success. The cast included her friend the soprano Caterina Galli, the tenor Thomas Lowe and perhaps Gaetano Guadagni in the part of Pleasure. |

| 1751 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital |

| 1751 | The Choice of Hercules | Pleasure | George Frideric Handel | première | The choice of Hercules and Alexander's feast were interpreted the same evening (1 March 1751) with great success. The cast included her friend the soprano Caterina Galli, the tenor Thomas Lowe and perhaps Gaetano Guadagni in the part of Pleasure. |

| 1751 | Esther | Esther | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1752 | Joshua | Achsah | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1752 | Jephtha | Iphis | George Frideric Handel | première | with the tenor John Beard. This is Handel's last oratorio |

| 1752 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital |

| 1753 | The Masque of Alfred | Eltruda | Thomas Arne | revival but première of the aria "Gracious Heav'n, O hear me!" | at the New Haymarket Theatre. Alfred was originally a concise masque the score of which Arne expanded for the 1753 charitable concert. Notably, he added the aria "Gracious Heav'n, O hear me!" to Act II, Scene 2, a piece composed specifically for Giulia Frasi.[4] |

| 1753 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital |

| 1754 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital. For this performance the transposed Guadagni arias were restored to the soprano voice.[9] |

| 1754 | 'Alexander Balus | Cleopatra | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1754 | Solomon | triple part of the two queens and the first prostitute | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital |

| 1754 | Deborah | Deborah | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1754 | Admeto | Antigona | George Frideric Handel | revival | with La Viscontina and the tenor Ottavio Albuzzi. |

| 1754 | L'allegro, il penseroso e il moderato | George Frideric Handel | revival | on the same day as Ode for St. Cecilia's day (23 May) | |

| 1754 | Ode for St. Cecilia's day | George Frideric Handel | revival | on the same day as L'allegro, il penseroso e il moderato (23 May) | |

| 1754 | Ipermestra[16] | Ipermestra | Giovanni Battista Lampugnani | revival | at the king's theatre, covering for Regina Mingotti and eventually taking over the role.[16] |

| 1755 | L'allegro, il penseroso e il moderato | George Frideric Handel | revival | revival on the same day as Ode for St. Cecilia's day (21 February) | |

| 1755 | Ode for St. Cecilia's day | George Frideric Handel | revival | revival on the same day as L'allegro, il penseroso e il moderato (21 February) | |

| 1755 | L'Olimpiade[16] | Argene | Baldassare Galuppi | revival | |

| 1755 | The Fairies | ? | John Christopher Smith | première | at the Drury Lane Theatre. Giulia is cast along with the famous castrato Gaetano Guadagni, next to whom she had one of her greatest successes. |

| 1755 | Ricimero, Re di Goti[16] | Ernelinda | Baldassare Galuppi | revival | at the king's theatre, covering for Regina Mingotti and eventually taking over the role.[16] |

| 1755 | Samson | triple part of Dalila, the Philistine and Israelite woman | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1755 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital. Handel was severely afflicted by the onset of blindness and he turned over the direction of the Messiah hospital performance to his pupil, John Christopher Smith[9] |

| 1755 | 'Joseph and his Brethren | Asenath | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1755 | Andromaca[16] | Ermione | Jommelli | revival | Commercial failure, only two performances[16] |

| 1755 | Andromaca[16] | Andromaca | Jommelli | revival | at the king's theatre, covering for Regina Mingotti and eventually taking over the role.[16] |

| 1755 | Demofoonte[16] | Creusa | Jommelli | revival | at the king's theatre on 9, 13, 16, 20, 27, 30 December and on 3, 10, 13, 17, 20, 24, 27, 31 January and 3 and 7 February.[16] |

| 1756 | Athalia | Josabeth | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1756 (?) | Andromaca[16] | Andromaca | Jommelli | revival | at the King's Theatre in lieu of Ezio by Davide Perez, taking over Regina Mingotti's role due to the latter's indisposition.[16] |

| 1756 | L'Olimpiade[16] | Argene | Baldassare Galuppi | revival | with additional arias by Felice Giardini, at the King's Theatre on 17 and 21 February, 6, 9, 13, 20, 23, 27 March and 6 April. Reprised again for benefits on 27, 29 April and 1 May[16] |

| 1754 | Ipermestra[16] (?) | Ipermestra | Giovanni Battista Lampugnani | revival | at the king's theatre on 25, 29 May and 3, 12, 19 June,[16] covering for Regina Mingotti (?) |

| 1756 | Eliza | ? | Thomas Arne | première | at the Drury Lane Theatre. |

| 1756 | Tito Manlio[16] | Sabine | Girolamo Abos | revival | |

| 1756 | 'Israel in Egypt | ? | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1756 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital, direction by John Christopher Smith[9] |

| 1756 | ? | ? | William Boyce | ? | at Hereford Cathedral for Three Choirs Festival. |

| 1757 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital. Handel comes back at the direction.[9] |

| 1757 | 'The Triumph of Time and Truth | Beauty | George Frideric Handel | première | |

| 1757 | Demetrio, re di Siria[17][18][19][20] | Barsene | Gioacchino Cocchi | revival | at the King's Theatre on 8, 12, 15, 19, 22, 26 and 29 November; 3, 6, 10, 13, 17, and 23 December. Recitatives in English and arias in Italian. |

| 1758 | Solomon | triple part of the two queens and the first prostitute | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital |

| 1758 | Issipile | Issipile | Gioacchino Cocchi | première | at the King's Theatre. In 1757 Gioacchino Cocchi came to England, and had several works represented there, but he failed to gain public's recognition as an opera composer. He then devoted himself to teaching singing for fifteen years, which allowed him to accumulate considerable wealth. He also published music in London.. He left London in 1773. |

| 1758 | Jephtha (?) | Iphis | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1758 | Belshazzar (?) | Nitocris | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1758 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital |

| 1758 | Zenobia[21][18][19] | Egle (shepherdess) | Gioacchino Cocchi | première | at the King's Theatre on 10, 14, 17, 21 and 28 January; 4, 11 and 18 February. Recitatives in English and arias in Italian |

| 1759 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital and at Covent Garden (the final performance of the work at which Handel was present: 6 April 1759, eight days before his death).[9] |

| 1759 | Judas Maccabaeus | Israelite woman | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1759 | The Masque of Alfred | Eltruda | Thomas Arne | revival | at Covent Garden |

| 1759 | Solomon | triple part of the two queens and the first prostitute | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Foundling Hospital |

| 1760 | Paradise lost | Eve | John Christopher Smith | première | role creation shared with Charlotte Brent |

| 1761 | Rebecca | Rebecca | John Christopher Smith | première | |

| 1763 | Telemachus | Parthenope | Philip Hayes | première | in Oxford. A projected London performance of Telemachus was advertised in 1764 but seems to have been cancelled.[4] |

| 1767 | Esther | Esther | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1767 | Messiah | soprano | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1769 | Judas Maccabaeus | Israelite woman | George Frideric Handel | revival | |

| 1769 | Artaxerxes | Arbaces | Thomas Arne | revival | organised by herself at the King's Theatre.

in aid of the Jermyn Lying-in Hospital.[4] A charity evening dedicated to the composer.[3] The role interpreted by Frasi was originally created in 1762 by the castrato Tenducci, also known as "the second" Senesino. Frasi had seldom performed trouser roles since her formative early years in London.[4] |

| 1770 | Judas Maccabaeus | Israelite woman | George Frideric Handel | revival | at the Little Theatre, at noon.

charity concert to her own benefit whose organisation is plagued with difficulties. |

| April 1774 | ? | ? | ? | ? | at the Little Theatre.with the very young Nancy Storacce.[4] |

| May 1774 | ? | ? | ? | ? | at Hickford's Room. |

Second part and end of career

Handel's last prima donna

.jpg.webp)

As of 1749 Giulia sings in all of the Covent Garden concerts that Handel gave for the rest of his life[4] and she remained Handel's Prima Donna in all his later seasons, creating and interpreting parts he often wrote specifically for her. Her greatest successes were Handel's oratorios.[3]

From 1750 Messiah had annual performances at the Foundling Hospital until Handel's death and beyond.[9] Based on Frasi's professional relationship with Handel and her involvement in charity, she is likely to have taken part in most of them. Indeed, David Vickers states that "Frasi participated in all of Handel's annual performances of Messiah, in the chapel of the Foundling Hospital (from 1750)."[4]

Many of Handel's oratorios had numerous revivals with her, including in provencial cities: Oxford in 1754, 1756, 1759, Salisbury in 1758, 1761, 1765, Ranelagh in 1751, 1752, and for nine consecutive years at the Three Choir festival (1756- 64).[3][2]

For instance:

On Saturday 22 June 1754 the Oxford Journal published the following advertising:[22]

On Wednesday the 3rd, Thursday the 4th and Friday the 5th of July, being the three Days following the Commemoration of Founders and Benefactors to the University, L'Allegro, il Penseroso, &c. Judas Macchabæus, and Messiah will be performed in the Theatre. The principal Vocal Parts by SIGNORA FRASI, Mr. BEARD, Mr. WASS, and others; and the Instrumental Parts by many of the most excellent Performers of every Kind from LONDON. Further particulars will be specified in the Bills of each Days Performance.

On Saturday 30 June 1759 the Oxford Journal published the following advertising:[23]

On Tuesday the 3rd of July (the Day of the Installation) will be performed, in the Theatre, the Oratorio of SAMSON; on Wednesday the 4th (the Day appointed for commemorating our Founders and Benefactors), the Oratorio of ESTHER; and on the 5th MESSIAH, or the SACRED ORATORIO; together with select pieces between the Acts (as will be specified in the Bill of each Days Performance) by a numerous and excellent Band from London, Bath and other Places. The principal Vocal Parts by Signora Frasi, Miss Brent, Mess. BEARD, CHAMPNES, WASS and HUDSON from London and Master NORRIS from Salisbury. TICKETS are to be had at Mr. Cross's Music Shop and at the Coffee Houses; Price FIVE SHILLINGS.

Throughout the 1750s, "Frasi's concert repertoire stretched from Purcell to Terradellas."[4] She was considered a paramount principal soprano in English oratorios or other works of the sort by Handel and by other composers. Frasi was at nine consecutive meetings of the Three Choirs Festival: she sang for William Boyce at Hereford in 1756, then she performed for Arne, and so on. She gave regular concerts in Oxford too. She also continued to be part of the Covent Garden oratorio concerts given by Handel and, later, by John Christopher Smith and John Stanley. (The latter two would produce their own oratorios (or other works suitable for the occasion) whilst also putting together revivals of Handel's.[4]) In fact, after Handel's death in 1759, Frasi continued as Prima Donna under his successors until about 1768.[3][2]

In total Frasi also participated in at least fourteen opera seasons at the King's Theatre between 1742 and 1761.[4] In addition to which, during the 1754-1756 seasons, Giulia regularly covered for Regina Mingotti. (Mingotti's fits of temper, antagonisms with the director of the opera company of the King's Theatre and ailings often made her "indisposed". Frasi covered for her many a time, more often than not ending up taking over Mingotti's role for the rest of the performances as Regina Mingotti "[would] not yet [have] recovered of her indisposition".[16] Michael Burden quotes the following newspaper clip:[16]

Signora Mingotti having acquainted Sig Vanneschi Yesterday Afternoon that she continues very much indisposed, and is not able to sing To morrow night, by which Reason the Opera called Ezio cannot be performed; instead thereof Sig. Vanneschi begs Leave to perform the Opera of Andromaca, in which Signora Frasi will do the part of Signora Mingotti; and Signora Peralta is to do the part of Signora Frasi.

During the 1760s, Frasi continued to play a prominent part in the musical life of London. She seems to have transitioned smoothly to the new music style of the generation of composers younger than her; composers like Philip Hayes, who announce the advent of the Classical Era.

She was part of the London Stage for about 31 years in total.[3] Aside from interpreting Handel's and other composers' music on stage, Giulia also continued to sing regularly in charity concerts; she also took part regularly in the annual Musicians Fund (and other) benefits, and sang at the Castle and Swan concerts, at Ranelagh and elsewhere.[2]

Progressive retirement

From 1764 onwards her public appearances became less frequent. In 1767 she appeared at London's Covent Garden in Esther and at Haberdashers' Hall in Messiah.[3]

She made her last appearances in 1769 in Handel's Judas Maccabaeus at the King's Theatre, and as Arbaces in Artaxerxes by Thomas Arne. The latter is her last known appearance on the stage in an opera.[3][4]

Finally, in 1770 - after having been "confined for some Time by a bad State of Health" - she appeared again at the Little Theatre for a charity concert to her own benefit singing Judas Maccabaeus.[3][4] But the organisation of the concert was plagued with difficulties which eventually lead her to give a "full-scale oratorio [...] at the unsociable hour of noon."[4] Three years later she appeared in a few concerts, making a new "come-back" about which The Morning Post and Daily Advertiser wrote sarcastically: "Signora Frazi, who may be said, with respect to the musical world, to have been long since dead and buried, is expected to rise again in Lent[.]" Vickers adds that "the soprano's comeback comprised a few scattered concerts at inauspicious venues".[4]

A significant musical figure

Giulia Frasi was not only able to quickly win over the London Opera Stage, but she had Handel's assent as well. She also gained the affection and became a favourite of the English public.

The thirty-one-year career that Frasi enjoyed in London was much broader and varied than being Handel's last prima donna. She also sang composers as varied as Gluck, the Venetian heritage style of Galuppi, the Neapolitans like Porpora, Pergolesi, Lampugnani, Hasse, Cocchi, and English composers, among which Boyce, Smith, Hayes and Arne.[1] Operas and oratorios on the London stage were a rather important part of her career but so was her music making in other occasions. She did have a non-negligeable place in London's community of musicians and participated in the cultural richness and musical diversity of London and Britain during the mid-Georgian Era.[4]

Ruby Hughes says of the roles written by Handel for Giulia Frasi that they "seem to engender a depth of female characterisation which may well have subverted the norm at a time". She adds that "Encountering Frasi through the music that was written for her, and contemplating her career as a musician, has been a tremendous source of inspiration" [...and that she is] "struck by the significance of [Frasi's] considerable achievements."[14]

Undoubtedly, Giulia Frasi was one of the significant musical figures of London from the 1740s to the 1760s.[1]

Death

Frasi's infamous profligacy inevitably caused problems when her vocal powers ran out. Her accumulated debts due to her expensive and extravagant lifestyle reduced her to poverty, so much so that, in her latest years, after her last documented concert at Hickford's Room on 16 May 1774, she found herself forced to flee to Calais where she died destitute.[3][2][4]

Discography

- There are countless commercial recordings of Handel's works, including the ones sung by Giulia Frasi.

- Handel's Last Prima Donna: Giulia Frasi In London. Ruby Hughes (soprano); Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Laurence Cummings. (Chaconne Hybrid SACD, Chandos CHSA0403, 2018). This CD is a tribute to Giulia Frasi and includes 4 world première recordings of works by Ciampi, Hayes and Smith. There is a historical and musicological essay by David Vickers in the CD booklet.

- Mozart in London. Helen Sherman (soprano); The Mozartists, Ian Page. (Signum Classics, B07BF2482X, 2018). This CD offers a musical landscape of the London of the 1760s. The tracklist encompasses works by J. C. Bach, Abel, Pescetti, Perez, Rush and Bates, many of which are world première recordings. It also includes two arias from Artaxerxes by Thomas Arne and both are arias Giulia Frasi would have sung in the 1763 revival: Act I, Scene 2: "Amid a thousand racking Woes" and Act I, Scene 13: "O too lovely, too unkind."

Notes

- "Giulia FRASI". Quell'Usignolo.

- Dean, Winton (2001). "Frasi [Frassi], Giulia". OxfordMusicOnline.

- Campi, Paola (1998). "Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani". Enciclopedia Treccani.

- Vickers, David (2008). Handel's last prima donna: Giulia Frasi in London. CHSA0403, Chaconne Super Audio CD. Colchester, England: Finn S. Gundersen & Chandos Early Music.

- Winton Dean. "Giulia Frasi". hemingways-studio.org.

- Gluck, Christoph Willibald (1746). The favourite songs in the opera call'd Artemene by Sigr. Gluck. London: I. Walsh. pp. 10–12.

- Croll, Gerhard. "Christoph Willibald Gluck, German composer". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Howell, Caro (2014). "How Handel's Messiah helped London's orphans – and vice versa". Guardian News & Media Limited.

- Shaw (1965). A Textual and Historical Companion to Handel's Messiah.

- Winton, Dean (2001). "Frederick, Cassandra". OxfordMusicOnline.

- "Brewer Street and Great Pulteney Street Area". British History Online. 1963.

- "Gerrard Street Area: The Military Ground, Gerrard Street". British History Online. 1966.

- Burney, Charles (1935) [1789]. F. Mercer (ed.). A General History of Music from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Oxford Publishing Company. p. 841.

- Hughes, Ruby (2018). Handel's last prima donna: Giulia Frasi in London. Foreword by the soloist. CHSA0403, Chaconne Super Audio CD. Colchester, England: Finn S. Gundersen & Chandos Early Music.

- Morin, Alexander J. (1998). "CD Review - George Frideric Handel, Alceste - Incidental Music HWV 45". ClassicalNet.

- Burden, Michael (2013). Regina Mingotti: Diva and Impresario at the King's Theatre, London. London: Royal Musical Association Monographs, Ashgate.

- Bucciarelli, Melania (2006). Italian opera in Central Europe. Berlín: Berliner Wissenschafts / Verlag.

- Pascual, Josep (2004). Guía Universal de la Música Clásica. Ed. Robinbook, ed.

- Ópera. Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft. 1999.

- Metastasio, Pietro (1751). Demetrio. Madrid: Ed. Lorenzo Francisco Mojados.

- Metastasio, Pietro (1740). Zenobia, dramma per musica da representarsi nell'imperial Favorita.

- "Oxford Journal - Saturday 22 June 1754". The Oxford Journal. 1754.

- "Oxford Journal - Saturday 30 June 1759 - Advertisements". The Oxford Journal. 1759.

References

- Vickers, David: Handel's last prima donna: Giulia Frasi in London. CHSA0403, Chaconne Super Audio CD. Colchester, England: Finn S. Gundersen & Chandos Early Music, 2008.

- Dean, Winton: "Frasi [Frassi], Giulia". (2001), OxfordMusicOnline.

- Campi, Paola, in "Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani", 1998. Enciclopedia Treccani.

- E. Ferrettini, C. W. Gluck, Torino 1914, p. 31

- P.H. Lang, Händel, Milano 1985, pp. 511 s., 536, 555, 560, 585

- A. Loewenberg, Annals of opera, I, 1597-1940, Genêve 1955, col. 228

- P.H. Highfill - K.A. Buenim - E.A. Langhans, A biographical Dict. of actors, actress, musicians... in London, 1660–1800, V, Carbondale, IL, 1978, pp. 398 s.

- W. Dean, "G. F.", in The New Grove Dict. of music and musicians, London 1980, VI, p. 808

- Diz. enc. univ. della musica e dei musicisti, App., pp. 292 s.

- BHO - British History Online

- New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2ª Ed. (2001)

- Bucciarelli, Melania (2006). Italian opera in Central Europe (La ópera italiana en Centroeuropa) (in English). Berlín: Berliner Wissenschafts / Verlag.

- Burden, Michael (2013). Regina Mingotti: Diva and Impresario at the King's Theatre, London. London: Royal Musical Association Monographs, Ashgate.

- Pascual, Josep (2004). Ed. Robinbook, ed. Guía Universal de la Música Clásica.. 8496222098. p. 445. ISBN 9788496222090. Consultado el 22 de octubre de 2010. (enlace roto disponible en Internet Archive; véase el historial y la última versión).

- AA., VV. (1999). Ópera. Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft.

- The New Grove Dict. of Opera, II, pp. 289 s.

- Metastasio, Pietro (1751). Demetrio. Ed. Lorenzo Francisco Mojados. Madrid.

- Howell, Caro (2014). "How Handel's Messiah helped London's orphans – and vice versa". Guardian News & Media Limited.

- Shaw (1965). A Textual and Historical Companion to Handel's Messiah.

- Burney, Charles (1935) [1789]. F. Mercer (ed.). A General History of Music from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Oxford Publishing Company.

- Morin, Alexander J. (1998). "CD Review - George Frideric Handel, Alceste - Incidental Music HWV 45". ClassicalNet

- Croll, Gerhard. "Christoph Willibald Gluck, German composer". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- The Oxford Journal (1754 and 1759), British Newspaper Archive

- http://www.quellusignolo.fr/