Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November c. 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Florentius and later added the name Gregorius in honour of his maternal great-grandfather.[2] He is the primary contemporary source for Merovingian history. His most notable work was his Decem Libri Historiarum (Ten Books of Histories), better known as the Historia Francorum (History of the Franks), a title that later chroniclers gave to it, but he is also known for his accounts of the miracles of saints, especially four books of the miracles of Martin of Tours. St. Martin's tomb was a major pilgrimage destination in the 6th century, and St. Gregory's writings had the practical effect of promoting this highly organized devotion.

Saint Gregory of Tours | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bishop of Tours | |

| Born | 30 November c. 538 Auvergne, Austrasia (now France)[1] |

| Died | 17 November 593 or 594[2] Tours, Kingdom of Orleans (now France) |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Feast | 17 November |

Biography

Gregory was born in Clermont, in the Auvergne region of central Gaul.[3] He was born into the upper stratum of Gallo-Roman society as the son of Florentius, Senator of Clermont, by his wife Armentaria II, niece of Bishop Nicetius of Lyon and granddaughter of both Florentinus, Senator of Geneva, and Saint Gregory of Langres. Gregory had several noted bishops and saints as close relatives (his family effectively monopolised the Bishoprics of Tours, Lyon, and Langres at the time of his birth), and, according to Gregory, he was connected to thirteen of the eighteen bishops of Tours preceding him by ties of kinship. Gregory's paternal grandmother, Leocadia, descended from Vettius Epagatus, the illustrious martyr of Lyon.

His father evidently died while Gregory was young and his widowed mother moved to Burgundy where she had property. Gregory went to live with his paternal uncle St. Gallus, Bishop of Clermont), under whom, and his successor St. Avitus, Gregory had his education. Gregory also received the clerical tonsure from Gallus. Having contracted a serious illness, he made a visit of devotion to the tomb of St. Martin at Tours. Upon his recovery, he began to pursue a clerical career and was ordained deacon by Avitus. Upon the death of St. Euphronius, he was chosen as bishop by the clergy and people, who had been charmed with his piety, learning, and humility. Their deputies overtook him at the court of King Sigebert of Austrasia, and being compelled to acquiesce, though much against his will, Gregory was consecrated by Giles, Bishop of Rheims, on 22 August 573, at the age of thirty-four.[3]

He spent most of his career at Tours, although he assisted at the council of Paris in 577.[3] The rough world he lived in was on the cusp of the dying world of Antiquity and the new culture of early medieval Europe. Gregory lived also on the border between the Frankish culture of the Merovingians to the north and the Gallo-Roman culture of the south of Gaul.

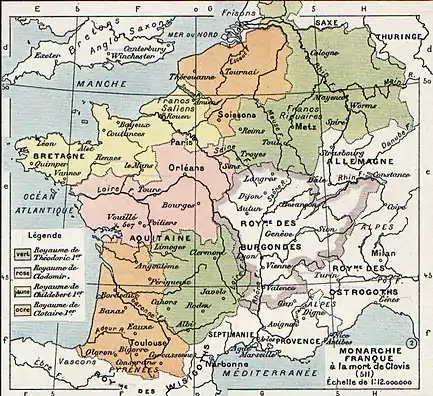

At Tours, Gregory could not have been better placed to hear everything and meet everyone of influence in Merovingian culture. Tours lay on the watery highway of the navigable Loire. Five Roman roads radiated from Tours, which lay on the main thoroughfare between the Frankish north and Aquitania, with Spain beyond. At Tours the Frankish influences of the north and the Gallo-Roman influences of the south had their chief contact (see map). As the center for the popular cult of St Martin, Tours was a pilgrimage site, hospital, and a political sanctuary to which important leaders fled during periods of violence and turmoil in Merovingian politics.

Gregory struggled through personal relations with four Frankish kings, Sigebert I, Chilperic I, Guntram, and Childebert II and he personally knew most of the leading Franks.

Works

Gregory wrote in Late Latin which departed from classical usage frequently in syntax and spelling with relatively few changes in inflection.[4]

Summary

Gregory of Tours' history is a dense work, full of numerous narratives and characters. Gregory's history contains Christian tales of miracles, descriptions of omens and natural events, stories of Christian martyrs, dialogues of church debates, lives of holy men, lives of the nobility, lives of eccentric peasants, frequent Bible verses and references, and complex international relations between numerous tribes and nations including the Lombards, Visigoths, Ostrogoths and Huns, not to mention Gregory's personal biography and interpretation of events.

Book I begins with the a pronouncement by the author, the Bishop of Tours, of Gregory's faith. That he is a Frankish Catholic clergyman who follows the Nicene Creed, and abhors heresy like those of the “wicked” Arian sect among other heresies. The Narrative history begins with a brief epitome of the Biblical Old Testament and New Testament, and the subsequent spread of the Christian Religion into Gaul. Next Gregory covers the history of Christianity in Gaul and some of the major events in Roman-Gallo relations. Book One ends with the death of Saint Martin of Tours in AD 397.

Book 2, AD 397-511, covers the beginnings of the Merovingian dynasty. Book Two ends with the death of King Clovis in 511, after his conquest of large tracts of land in modern-day France. Also narrated is Clovis's conversion to Christianity by his wife Clotilde.

Book 3, AD 511-548, follows the four male inheritors of King Clovis who equally divide his realms at his death in AD 511. These four kings, Theodoric I, Lothar I, Childebert, and Chlodomer, quarrel and fight for supremacy of the Frankish realm. Despite their disputes, the four brothers can occasionally work together against an outside threat, such as successful cooperation against the Burgundians in 523. Eventually Clothar becomes the most powerful King in the Frankish realm. Book Three ends with the death of king Theudebert I in 548. He is a grandson of Clovis and son to king Theodoric I, who died in 534 bequesting his kingdom to Theudebert. The kingdom after 548 falls to Theudobald I until 555.

Book 4, AD 548-575. The two remaining sons of Clovis die; King Childebert in 558 and King Clothar in 561. The last years of his life see the entire realm of the Franks ruled by Clothar. At the time of his demise in AD 561 (like Clovis before him), the Kingdom is divided equally between four sons of Clothar and again the kingly sons quarrel for control of the entire Kingdom. A truce between the brothers is maintained until after the death of King Charibert I (son of Clothar) in 567. Clothar's remaining sons, Kings Sigibert, Guntram, and Chilperic, fight for the supremacy of the kingdom, with King Sigibert showing the strongest military force. Book Four ends with the killing of King Sigbert in AD 575. Gregory of Tours blames Fredegund, the wife of King Chilperic, for this assassination. The death leaves King Chilperic as the dominant king. Fredegund has long held a grudge against King Sigibert and his wife Brunhilda.

Book 5, AD 575-581. This book begins the part of the narrative where the author (Bishop Gregory of Tours) has much personal knowledge about the events in the Frankish Kingdom. This book and the ones hereafter, are considerably longer and more detailed than previous, whilst covering a smaller amount of time. This book also contains Gregory's impressions of ecclesiastical issues he saw in person and had some bearing on. This book describes a possible debate that Gregory had with a rival Arian church leader. Book 5 also introduces Childebert II, the son of recently slain King Sigibert, and of the still living Brunhilda. Childebert is taken along with Brunhilda under the protection of King Gunthram, brother and sometime rival of King Chilperic.

Book 6, AD 581-584. The young Childebert betrays his alliance with his adoptive uncle King Gunthram, the king who had protected Childebert and his mother after his father Sigibert's death. Now Childebert forms an alliance with his uncle, King Chilperic, who had often been an enemy of King Sigibert. Later, King Chilperic is murdered under mysterious circumstances in AD 584.

Book 7, AD 584. Fredegund assumes regency for her young son Clothar II. In the future Clothar will be king of all Franks until his death in 619, but that is beyond Gregory's narrative which end in roughly AD 593. Fredegund and her son are under the protection of King Gunthram. She remains in power until her death in AD 597. Also in this book is the rebellion of Gundovald and its failure. Gundovald claimed to be a lost illegitimate son of dead King Chlothar I. Many of the Frankish nobles and the Byzantine emperor Maurice gave some support to this rebellion; however, it is swiftly crushed by King Guntram.

Book 8, AD 585.

Book 9, AD 586-587. The Treaty of Andelot is signed in AD 587 between King Guntram, Brunhilda, and King Childebert II. The treaty is a close pact of alliance, wherein Childebert is formally adopted as Guntram’s heir. Brunhilda also formally allies with Guntram and comes under his protection.

Book 10, AD 587-591. Around 589, Basina the daughter of King Chilperic I and Clotilda, daughter of King Charibert lead a brief revolt from a nunnery. The 18 Bishops of Tours are named and described. Book Ten ends with a summary of Gregory's previous written works.

The Historia Francorum is made up of ten books. Books I to IV initially recount the world's history from the Creation (as was traditional);[5] but move quickly on to the Christianization of Gaul, the life and times of Saint Martin of Tours, the conversion of the Franks and the conquest of Gaul under Clovis,[6] and the more detailed history of the Frankish kings down to the death of Sigebert I in 575. At this date Gregory had been bishop of Tours for two years.

With his fifth book, Gregory embarks (with some relief) on contemporary history, opening “Here, I am glad to say, begins Book V”.[7] This, the second part of his history, books V and VI, closes with Chilperic I's death in 584. During the years that Chilperic held Tours, relations between him and Gregory were tense. After hearing rumours that the Bishop of Tours had slandered his wife, Fredegund, Chilperic had Gregory arrested and tried for treason – a charge which threatened both Gregory's bishopric and his life.[2] The most eloquent passage in the Historia is the closing chapter of book VI, in which Chilperic's character is summed up unsympathetically through the use of an invective: Herod and Nero are among the comparisons employed.[8]

The third part, comprising books VII to X, takes his increasingly personal account to the year 591, and concludes with a plea for further chroniclers to preserve his work in entirety (as indeed would be done).[9] An epilogue was written in 594, the year of Gregory's death.

Problems of interpretation

Readers of the Historia Francorum must decide whether this is a royal history and whether Gregory was writing to please his patrons. It is likely that one royal Frankish house is more generously treated than others. Gregory was also a Catholic bishop, and his writing reveals views typical of someone in his position. His views on perceived dangers of Arianism, still strong among the Visigoths,[10] led him to preface the Historia with a detailed expression of his orthodoxy on the nature of Christ. In addition, his ridiculing of pagans and Jews reflected how his works were used to spread the Christian faith. For example, in book 2, chapters 28-31, he describes the pagans as incestuous and weak and then describes the process by which newly converted King Clovis leads a much better life than that of a pagan and is healed of all the conundrums he experienced as a pagan.

Gregory's education was the standard Latin one of Late Antiquity, focusing on Virgil's Aeneid and Martianus Capella's Liber de Nuptiis Mercurii et Philologiae, but also other key texts such as Orosius's Chronicles, which his Historia continues, and Sallust; he refers to all these works in his own. His education, as was typical for the time, did not extend to a broad acquaintance with the pagan classics,[11] but rather progressed to mastery of the Vulgate Bible.[12] It is said that he constantly complained about his use of grammar.[13] He did not understand how to correctly write masculine and feminine phrases, reflecting either a lack of ability or changes in the Latin language. Though he had read Virgil, considered the greatest Latin stylist, he cautions that "We ought not to relate their lying fables, lest we fall under sentence of eternal death." By contrast, he seems to have thoroughly studied the lengthy and complex Vulgate Bible, as well as numerous religious works and historical treatises, which he frequently quotes, particularly in the earlier books of the Historia.

The main impression that historians once retained from the Historia focused on Gregory's anecdotes about violence;[14] until recently, historians tended to conclude that Merovingian Gaul was a chaotic, brutal mess. Recent scholarship has refuted that view. Through more careful readings, scholars have concluded that Gregory's underlying purpose was to highlight the vanity of secular life and contrast it with the miracles of the Saints.[15] Though Gregory conveys political and other messages through the Historia, and these are studied very closely, historians now generally agree that this contrast is the central and ever-present narrative device.

Hagiographies

His Life of the Fathers comprises twenty hagiographies of the most prominent men of the preceding generation, taking in a wide range the spiritual community of early medieval Gaul, including lives of bishops, clerics, monks, abbots, holy men and hermits. St. Illidius is praised for his purity of heart, St. Brachio the abbot for his discipline and determination in study of the scriptures, St Patroclus for his unwavering faith in the face of weakness, and St. Nicetius, bishop of Lyon, for his justice. It is the life of St. Nicetius of Trier, though, which dominates this book; his great authority and sense of episcopal responsibility which is the focus of Gregory's account as his figure, predestined to be great, bestrides the lives of the others. It is told that he felt a weight on his head, but he was unable to see what it was when turning around, though upon smelling its sweet scent he realised that it was the weight of episcopal responsibility. (Life of the Fathers, XVII, 1) He surmounts the others in the glory of his miracles, and was chosen by God to have the entire succession of past and future Frankish kings revealed to him.

A further aspect of this work to note is the appearance of Gregory himself in certain sections, notably in the life of St. Leobardus. This is for two reasons: Firstly, it creates a distinct link between the temporal and the spiritual worlds, firmly placing the accounts of the lives in a world which is understandable and recognisable, or, seen from the other angle, confirming the presence of miracles in the temporal world. Secondly, the intercession of Gregory serves to set Leobardus straight, after he had been tempted by the devil (Life of the Fathers, XX, 3), and so this act further enhances the authority of bishops as a whole.

In 587 Gregory began writing the Book of the Glories of the Martyrs (Liber in gloria martyrum), which deals “almost exclusively with the miracles wrought in Gaul by the martyrs of the Roman persecutions.”[16] But it also tells the story of one Theodore who made a pilgrimage to India and reported the existence of a large monastery where the body of Thomas the Apostle was first interred and where miracles took place.[17]

Fighting heresy

Gregory's avowed aim in writing this book was to "fire others with that enthusiasm by which the saints deservedly climbed to heaven", though this was not his sole purpose, and he most surely did not expect his entire audience to show promise of such piety as to witness the power of God flowing through them in the way that it did for the fathers. More immediate concerns were at the forefront of his mind as he sought to create a further layer of religious commitment, not only to the Church at Rome, but to local churches and cathedrals throughout Gaul. Along with his other books, notably the Glory of the Confessors, the Glory of the Martyrs and the Life of St. Martin, meticulous attention is paid to the local as opposed to the universal Christian experience. Within these grandiloquent lives are tales and anecdotes which tie miracles, saints and their relics to a great diversity of local areas, furnishing his audience with greater knowledge of their local shrine, and providing them with evidence of the work of God in their immediate vicinity, thus greatly expanding their connection with and understanding of their faith. Attacks on heresy also appear throughout his hagiographies, and Arianism is taken to be the common face of heresy across Europe, exposed to great ridicule. Often, the scenes which expose the weaknesses of heresy (Glory of the Martyrs, 79, 80) focus on images of fire and burning, whilst the Catholics are proved right by the protection lavished on them by God.

This was of great relevance to Gregory himself as he presided over the important see of Tours, where extensive use was made of the cult of St. Martin in establishing the authority of the bishopric with the congregation and in the context of the Frankish church. Gregory's hagiography was an essential component of this. However, this should not be seen as a selfish grab for power on behalf of the bishops who emerge so triumphantly from the Life of the Fathers, but rather as a bid for hegemony of doctrine and control over the practice of worship, which they believed to be in the best interests of their congregation and the wider church.

Gregory's Creed

As an example of Gregory's zeal in his fight against heresy, the Historia Francorum includes a declaration of faith with which Gregory aimed to prove his orthodoxy with respect to the heresies of his time ("so that my reader may have no doubt that I am Catholic for they are.").[18] The confession is in many phrases, each of which refutes a specific Christian heresy. Thus Gregory's creed presents, in the negative, a virtual litany of heresies:

I believe, then, in God the Father omnipotent. I believe in Jesus Christ his only Son, our Lord God, born of the Father, not created. [I believe] that he has always been with the Father, not only since time began but before all time. For the Father could not have been so named unless he had a son; and there could be no son without a father. But as for those who say: "There was a time when he was not," [note: A leading belief of Arian Christology.] I reject them with curses, and call men to witness that they are separated from the church. I believe that the word of the Father by which all things were made was Christ. I believe that this word was made flesh and by its suffering the world was redeemed, and I believe that humanity, not deity, was subject to the suffering. I believe that he rose again on the third day, that he freed sinful man, that he ascended to heaven, that he sits on the right hand of the Father, that he will come to judge the living and the dead. I believe that the holy Spirit proceeded from the Father and the Son, that it is not inferior and is not of later origin, but is God, equal and always coeternal with the Father and the Son, consubstantial in its nature, equal in omnipotence, equally eternal in its essence, and that it has never existed apart from the Father and the Son and is not inferior to the Father and the Son. I believe that this holy Trinity exists with separation of persons, and one person is that of the Father, another that of the Son, another that of the Holy Spirit. And in this Trinity confess that there is one Deity, one power, one essence. I believe that the blessed Mary was a virgin after the birth as she was a virgin before. I believe that the soul is immortal but that nevertheless it has no part in deity. And I faithfully believe all things that were established at Nicæa by the three hundred and eighteen bishops. But as to the end of the world I hold beliefs which I learned from our forefathers, that Antichrist will come first. An Antichrist will first propose circumcision, asserting that he is Christ; next he will place his statue in the temple at Jerusalem to be worshiped, just as we read that the Lord said: "You shall see the abomination of desolation standing in the holy place." But the Lord himself declared that that day is hidden from all men, saying; "But of that day and that hour knoweth no one not even the angels in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father alone." Moreover we shall here make answer to the heretics [note: the Arians] who attack us, asserting that the Son is inferior to the Father since he is ignorant of this day. Let them learn then that Son here is the name applied to the Christian people, of whom God says: "I shall be to them a father and they shall be to me for sons." For if he had spoken these words of the only begotten Son he would never have given the angels first place. For he uses these words: "Not even the angels in heaven nor the Son," showing that he spoke these words not of the only-begotten but of the people of adoption. But our end is Christ himself, who will graciously bestow eternal life on us if we turn to him.[19]

Legacy

The Historia Francorum is of salient historical interest, representing as it does the central narrative with respect to the Franks for the period of transition from Roman to Medieval, and the establishment of the large and important Frankish state.[20] With his lively style, story-telling ability, and skill in conveying human interest, Gregory has been compared to Herodotus;[21] with his detailed interest in, and accounts of, ecclesiastical history and manoeuvrings, to a bloodier Trollope.[22]

Gregory's hagiographies are also an invaluable source of anecdotes and stories which enrich modern understanding of life and belief in Merovingian Gaul. The motivation behind his works was to show readers the importance and strength of Christianity. Alongside Venantius Fortunatus, he is the outstanding literary figure from the 6th century Merovingian world;[23] and his extensive literary output is itself a testimony to the preservation of learning and to the lingering continuity of Gallo-Roman civic culture through the early Middle Ages.

Notes

- Jones, Terry. "Gregory of Tours". Patron Saints Index. Archived from the original on 2007-01-10. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- Leclercq, Henri. "St. Gregory of Tours." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. New York, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 26 October 2014.

- Butler, Alban. The Lives of the Saints, Vol. XI, 1866

- Sandys, John Edwin. History of Classical Scholarship, Vol I. 434-435. Cambridge: CUP, 1903.

- J Burrow, A History of Histories (London 2007) p. 198

- J M Wallace-Hadrill, The Barbarian West (London 1952) p. 71-2

- Quoted in J Burrow, A History of Histories (London 2007) p. 205

- J B Bury ed., The Cambridge Medieval History Vol II (Cambridge 1926) p. 122

- J Burrow, A History of Histories (London 2007) p. 210

- J Burrow, A History of Histories (London 2007) p. 204

- J Burrow, A History of Histories (London 2007) p. 200

- Thorpe, Lewis (1974). The History of the Franks. London: Penguin Books. pp. 30. ISBN 978-0-14-044295-3.

- Gregory of Tours, The History of the Franks. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974, p. 63.

- J Burrow, A History of Histories (London 2007) p. 203-4

- See especially Goffart (1988) and Mitchell and Wood (2002)

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- Robert Silverberg, The Realm of Prester John, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1972, page 27.

- Book I.i

- Gregory of Tours (539-594): History of the Franks: Books I-X "In Christ's Name Here Begins The First Book Of The Histories." Medieval Sourcebook

- J. M. Wallace-Hadrill, The Barbarian West (London 1964) p. 91

- H.M. Gwatkin ed., The Cambridge Medieval History Vol II (Cambridge 1926) p. 157

- J. Burrow, A History of Histories (Penguin 2009) p. 208-9

- H.M. Gwatkin ed., The Cambridge Medieval History Vol II (Cambridge 1926) p. 156

References

The following represent key modern texts on Gregory of Tours, including the most recent translations of his work.

While Lewis Thorpe's translation of The History of the Franks is more accessible than Brehaut's, his introduction and commentary are not well regarded by contemporary historians (see Secondary Sources, below).

Editions

- Gregorii episcopi Turonensis. Libri Historiarum X (ed. Bruno Krusch and Wilhelm Levison), MGH SRM I 1, Hannover2 1951

- Miracula et opera minora (ed. Bruno Krusch), MGH SRM I 2, Hannover 1969, 211-294 (repr. from 1885)

Translations

- Fränkische Geschichte. 3 vols. (transl. by Wilhelm von Giesebrecht, rev. by Manfred Gebauer), Essen 1988.

- From Roman to Merovingian Gaul. A Reader (ed. and transl. Alexander Callander Murray; Readings in medieval Civilisations and Cultures 5), Toronto 2000, 287-446

- Glory of the confessors (ed. and transl. Raymond Van Dam; Translated Texts for Historians 4), Liverpool 2004 (2nd edition), ISBN 0-85323-226-1.

- Glory of the Martyrs (ed. and transl. Raymond Van Dam; Translated Texts for Historians 3), Liverpool 2004 (2nd edition), ISBN 0-85323-236-9.

- Liber de passione et virtutibus sancti Iuliani martyris und Libri de virtutibus sancti Martini episcopi, in: Raymond Van Dam (ed.), Saints and their Miracles in Late Antique Gaul, Princeton 1993, 153-317.

- Life of the Fathers (ed. and transl. James Edward; Translated Texts for Historians 1), Liverpool 1991 (2nd edition), ISBN 0-85323-327-6.

- The History of the Franks (transl. M. Dalton), Oxford 1927.

- The History of the Franks (transl. L. Thorpe), Penguin 1974.

- Historias (transl. P. Herrera), Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Extremadura, 2013, ISBN 978-84-7723-190-5

- Histoire des Franks, in French

Bilingual editions

- Les livres des miracles et autres opuscules de Georges Florent Grégoire évêque de Tours (ed. and transl. Léonard Bordier), vol. 1, Paris 1857.

- Zehn Bücher Geschichten. Band I-II.(ed. and transl. Wilhelm Giesebrecht and Rudolf Buchner), Darmstadt 1955-1956.

Secondary sources

- Brown, Peter, The Cult of the Saints, London 1981.

- Goffart, Walter, The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550–800), Princeton 1988.

- Diem, Albrecht, “Gregory’s Chess Board: Monastic Conflict and Competition in Early Medieval Gaul”, in Compétition et sacré au haut Moyen Âge: entre médiation et exclusion, Philippe Depreux, François Bougard and Régine Le Jan (eds.), Brepols, Turnhout 2015, pp. 165–191.

- Heinzelmann, Martin, Gregory of Tours: History and Society in the Sixth Century, trans. Christopher Carroll, Cambridge 2001.

- James, E.,The Franks, Oxford 1988.

- Kaiser, Reinhold, Das römische Erbe und das Merowingerreich, München 2004 (Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte 26).

- Loseby, S.T., “Marseille and the Pirenne thesis, I: Gregory of Tours, the Merovingian kings and 'un grand port'” in The Sixth Century. Production, Distribution and Demand, edited by Richard Hodges and William Bowden, pp. 203–229, Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden 1998.

- Loseby, S.T., “Gregory's cities: urban functions in sixth-century Gaul”, in Franks and Alamanni in the Merovingian period: an Ethnographic Perspective, edited by Ian N. Wood, pp. 239–270, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, Woodbridge 1998.

- McSheffrey, Shannon, The History of the Franks, Harmondsworth 1974.

- Mitchell Kathleen, Wood Ian (eds.), The World of Gregory of Tours, Leiden 2002.

- Murray, A.C. (ed.), A Companion to Gregory of Tours, Leiden 2016.

- Serra, Antonio, “L’ingenium artis di Gregorio di Tours. Preliminari d’indagine”, Invigilata Lucernis 32 (2010), pp. 157-175.

- Van Dam, Raymond, Saints and their miracles in late antique Gaul, Princeton 1993.

- Wood, Ian N., The Merovingian kingdoms 450-751, London 1994.

- Wood, Ian N., Gregory of Tours, Bangor (GB) 1994.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gregory of Tours. |

- Gregory of Tours (c. 538-594 A.D.). "Historiae, Libri X" (in Latin). The Latin Library.

- Gregory of Tours (539-594) (1997) [1916]. Halsall, Paul (ed.). History of the Franks: Books I-X (Abridged). Translated by Earnest Brehaut. Medieval Sourcebook, Fordham University.

- S. Georgii Florentii Gregorii Turonensis Episcopi (1994) [1853]. Friedrich Haase (ed.). liber ineditus De cursu stellarum: ratio qualiter ad officium implendum debeat observari: sive de cursibus ecclesiasticis (in Latin). Bratislava: Jos. Max et Soc.; Dolnośląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa (dbc).

- Staatsbibliothek Bamberg Msc.Patr.61, the primary witness of De cursu stellarum

- Gregorius (2011) [1857-1864]. Les livres des miracles et autres opuscules de Georges Florent Grégoire (in Latin and French). Translated by Henri Léonard Bordier. Paris: J. Renouard.

- History lecture by Paul Freedman on Procopius and Gregor of Tours in Yale University (fall 2011): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pbN8OTHecuI