Griffith Rutherford

Griffith Rutherford (c. 1721 – August 10, 1805) was an officer in the American Revolutionary War, a political leader in North Carolina, and an important figure in the early history of the Southwest Territory and the state of Tennessee.

Griffith Rutherford | |

|---|---|

Memorial for Griffith Rutherford in Murfreesboro, Tennessee | |

| Born | 1721 Ireland |

| Died | August 10, 1805 (aged 84) Sumner County, Tennessee |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | North Carolina militia |

| Years of service | Colonial Militia 1760–1775

North Carolina Militia 1775–1783 |

| Rank | Colonial Militia

North Carolina Militia

|

| Unit | North Carolina militia |

| Commands held | Salisbury District Brigade, Rowan County Regiment |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War |

| Relations | Married to Elizabeth Graham |

| Other work | Served in the North Carolina senate, settled in Sumner County, Tennessee, became President of the Legislative Council of the Southwest Territory (Tennessee) |

| Signature | |

During the French and Indian War, Rutherford became a captain of a local British colonial militia. He continued serving in the militia until the start of the revolution in 1775, at which time he enlisted in the North Carolina militia as a colonel. He was appointed to the post of brigadier general of the "Salisbury District Brigade" in May 1776, and participated in the initial phases of the Cherokee–American wars against the Cherokee Indians along the frontier. In June 1780, he was partly responsible for the Loyalist defeat in the Battle of Ramsour's Mill. Rutherford was present at the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780, where he was taken prisoner by the British. After being exchanged in 1781, Rutherford participated in several other campaigns, including further attacks on the Chickamauga faction of the Cherokee.

Originally from Ireland, Rutherford immigrated with his parents to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Colony, at the age of eighteen. In 1753 he moved to Rowan County, in the Province of North Carolina, where he married Elizabeth Graham. An active member of his community, Rutherford served in multiple civil occupations. He was a representative of both houses of the North Carolina House of Commons, as well as an unsuccessful candidate for governor. Rutherford was an advocate of the anti-federalist movement and was appointed President of the Legislative Council of the Southwest Territory in 1794. Rutherford retired to Sumner County, Tennessee, where he died on August 10, 1805, at the age of 84.

Early life

Little is known about Griffith Rutherford's early life. Born in Ireland in either 1721 or 1731[1] to John Rutherford, who was of Ulster Scots descent, and Elizabeth (née Griffin), who was of Welsh descent,[2] he appears clearly in records after his immigration to Philadelphia at the age of eighteen.[3] His parents died during the voyage from Ireland, and for a while he worked on a relative's farm,[3] where he was taught how to survey land.[4] Around 1753, he moved to Rowan County, North Carolina Colony, and bought a tract of land about seven miles (11 km) from Salisbury; this was the first of several land purchases he made during the 1750s.[5] The following year Rutherford married his neighbor's sister, Elizabeth Graham, who eventually bore him ten children.[2][6] One of their sons, James Rutherford, later became a major during the Revolutionary War, dying at the Battle of Eutaw Springs.[7] Rutherford also became friends with Daniel Boone during this time, with whom he often went on hunting and surveying expeditions.[8] After the French and Indian War, Rutherford became increasingly active in community affairs. He was listed as a member of the North Carolina General Assembly in 1766, a sheriff and justice of the peace of Rowan County from 1767 to 1769, and a tax collector.[9]

French–Indian War

Rutherford began his extensive military career in 1760 during the French and Indian War. He was a participant in several battles and skirmishes, most notably the Battle of Fort Duquesne (1758); the battle at Fort Dobbs (1760); and James Grant's campaign against the Cherokee in the southern Appalachians (1761). By the war's end, he had achieved the rank of captain.[10] Between 1769 and 1771, he embraced the cause against the rebels during the Regulator Movement, commanding a local militia which participated in the Battle of Alamance (May 16, 1771). The following month, Rutherford retired to Salem to recover from an acute attack of gout.[11]

Revolutionary War

Rutherford entered the war in 1775 as a colonel in the North Carolina militia following his appointment to the Rowan County Committee of Safety.[12] Throughout that year, his regiment helped to disarm and disperse Loyalist groups in the South Carolina back country, most notably during the Snow Campaign in Ninety Six, South Carolina.[13] Rutherford represented Rowan County at the Fourth Provincial Congress in Halifax from April 4 to May 14, 1776, during which he helped develop and write the Constitution of North Carolina and was promoted to brigadier general of the Salisbury District Brigade.[3][14] In the summer following the conference, he raised an army of 2,400 men to campaign against local Cherokee Indians,[14] who had been attacking colonists on the western frontier since their alliance with the British.

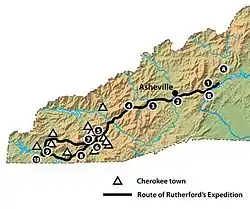

Campaign against the Cherokee

Rutherford's regiment rendezvoused at Fort McGahey with the Guilford and Surry County regiments under Colonels James Martin and Martin Armstrong on July 23, 1776.[14] From there, the three groups traveled through the Blue Ridge Mountains at the Swannanoa Gap, passed up the valley of Hominy Creek, and crossed the Pigeon River. They then passed through Richland Creek, near the present day town of Waynesville, North Carolina, and crossed the Tuckasegee River near an Indian settlement. They moved further onwards towards the Cowee Gap, where they had a small engagement with a band of Cherokee, in which one of Rutherford's men was wounded. After that conflict, they marched to the Overhill Cherokee "Middle Towns" (on the Tennessee River), where he met General Andrew Williamson of South Carolina on September 14[15] at Hiwassee.[16] Williamson was on a similar mission and readily joined forces with the original three regiments.[15]

The now four regiments skirmished with hostile Indians at Valley Town, Ellijay, and near the southern Watauga settlements (present day northeast Tennessee). Eventually, the Indian tribes were subdued at the cost of three fatalities to Rutherford's regiment.[15] Casualties to the Indians, however, were severe. By the end of the conflict, the four regiments had destroyed 36 Indian towns, decimated acres of corn farms, and chased off most of the Indians' cattle.[17] Afterward, Rutherford returned home by the same route.[15] He arrived back in Salisbury in early October, where he disbanded his troops.[15]

Later that month, Rutherford authorized another punitive expedition of a recently raised cavalry force, led by Captain William Moore joined by Captain Joseph Harden[18] of the Tryon County Regiment (North Carolina), to attack the Middle Towns.[19]

Southern theater

British strategists viewed the Southern colonies, especially lightly populated Georgia, as the most vulnerable of all. Despite early victories won by the Patriots at Charleston and other settlements, the South became the focus of English attack starting in 1778. Governor Richard Caswell of North Carolina identified this threat and immediately ordered militia to regroup. Rutherford, who had been checking on Loyalists since his return to Salisbury in 1776, received word of this by October.[20] Governor Caswell and Rutherford met in Kinston, North Carolina, on November 25 to discuss the specifics of Rutherford's assignment. Apparently a fleet of British ships were en route from New York, heavily endangering key coastal cities. Rutherford was able to amass a force which reached the border of South Carolina by early December. They proceeded to establish headquarters near Savannah in Purrysburg, South Carolina, the following month.[21]

With the cities of Savannah and Augusta taken by February, the campaign was severely weakened. Rutherford moved his troops near Augusta, where he supported General John Ashe during the Battle of Brier Creek on March 3.[22] Soldiers' enlistments soon began expiring; by April 10 most of Rutherford's forces returned to North Carolina.[23]

The loss of Charleston in 1780 was a huge blow to the Patriot cause and posed a significant threat to neighboring North Carolina, which lacked adequate defenses due to expiring enlistments. Rutherford saw this danger, calling back his remaining troops stationed in South Carolina and ordering all soldiers from Salisbury to rally near Charlotte, North Carolina. A force of 900 had accumulated by early June.[24][25]

Battle of Ramsour's Mill

After rallying troops at Charlotte, Rutherford received information that Loyalists were gathering at arms at Ramsour's Mill—near present-day Lincolnton, North Carolina—and issued orders for local officers to disperse the group before they evolved into an even greater threat. After collecting troops from Rowan and Mecklenburg counties, Rutherford moved his men to the Catawba River and crossed it at the Tuckasegee Ford on June 19. He sent word to Colonel Francis Locke of Rowan County, to rendezvous with him about 16 miles (26 km) from Ramsour's Mill, near the forks of the Catawba.[26] Locke accumulated a force of 400 men and encamped at Mountain Creek, which was 35 miles (56 km) away from Rutherford's position, though still approximately the same distance from Ramsour's Mill as Rutherford's position was. It was resolved by Locke and his officers that a junction with Rutherford was unrealistic given the distance between the two regiments and the limited amount of time before the Loyalist group grew too large to safely engage. Therefore, it was decided Locke's forces would attack the Loyalist's position immediately. Colonel Johnson, one of Locke's subordinates, informed Rutherford of the new situation by 10:00 pm.[24]

Locke's forces left their encampment late in the evening of June 19; arriving at the Loyalist position by early morning, June 20. The Patriots took the Loyalists by surprise. While at first bewildered and confused, the Loyalists retaliated by firing at Locke's cavalry, who were forced to fall back. The Patriots eventually forced the Loyalists to retreat to their camp, though it was discovered that they were regrouping on the other side of the mill stream. At this point, since an immediate attack from the Loyalists was expected, messages were sent to Rutherford, who had advanced to within six miles (9.6 km) of Ramsour's, to immediately move forward.[26] Rutherford met Locke within 2 miles (3.2 km) of Ramsour's, where he was informed that the Loyalists were in full retreat.[26]

Battle of Camden

The losses at Savannah, Charleston and the Battle of Waxhaws had practically driven the Continental Army from the South, with State defenses reduced to a number of locally-lead partisan militias. In response to the loss of military presence, Congress sent Horatio Gates, who had distinguished himself at Saratoga, to reform the Continental Army in Charlotte, North Carolina.[27] Against the advice of his officers and without knowing the capabilities of his troops—some of which were untested in battle—Gates marched toward South Carolina on July 27 with over 4,000 men. He aimed to capturing the crossroads town of Camden, South Carolina, which would have been strategically important for control over the South Carolina backcountry. Lord Rawdon, who was stationed there with 1,000 men, alerted Lord Cornwallis of Gates's movements on August 9. Cornwallis arrived at Camden by August 13 with reinforcements, increasing the British presence there to over 2,000 men.[28]

The battle ensued at dawn on August 16, 1780. Rutherford was positioned in the center of the Continental formation with other North Carolina militia. During the battle, he was wounded and taken prisoner. He was detained for ten months at Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida, and was later exchanged for another prisoner in 1781.[29][30]

Later war

Rutherford returned to Salisbury in September 1781 after his release to find his home ransacked by British troops.[30] After a short reunion with his family, Rutherford trained and took command of 1,400 men of the Salisbury District Brigade and allegedly began to brutally attack Tory militias and communities according to several reports sent to his superior, General Greene.[31] Greene disagreed with Rutherford's tactics, warning Rutherford that these methods would only encourage the Loyalist cause.[32] While these reports were later found to be false, Rutherford decided to redirect his forces towards the British encampment and surrounding militias at Wilmington, North Carolina, beginning with the Loyalist force at Raft Swamp.[33] During October and November, Rutherford continued to force the Loyalists into Wilmington, and eventually surrounded the city, successfully cutting off British communications and supply lines. The commanding British officer, Major Craig, was soon afterward informed of Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown, and his forces at Wilmington were hastily evacuated.[15][34]

After Wilmington, Rutherford again fought the Chickamauga in the west in 1782.[3] He followed the same route he had taken seven years before. No known accounts were written of the campaign, though it was reportedly successful.[35]

Later life

Rutherford was elected to North Carolina's senate during the War in 1779 and continued to serve in this position until 1789. He opposed the restoration of Loyalist lands, supporting and assisting in their confiscation while serving in the Council of State. Rutherford ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1783. He was an ardent anti-federalist during the national debate on the recently created United States Constitution. At a Constitutional Convention held at Hillsborough, North Carolina in 1788, he had reservations about the Constitution—as did other anti-federalists at the meeting. Rutherford requested if he could challenge some of the clauses.[36] While each clause was challenged individually despite opposition from federalist Samuel Johnston and others, Rutherford rarely contributed to discussion.[36] His final decision to vote against the ratification of the Constitution resulted in him losing his seat in the state senate. However, his reputation with his colleagues was relatively unaffected, and he was subsequently elected Councilor of the State.[37]

Rutherford acquired nearly 13,000 acres of Washington District land through trading off his 700 acres in Salisbury, government grants and purchasing Continental soldier's tracts.[38] With his family and eight slaves Rutherford relocated to this area, in what is today Sumner County, Tennessee, in September 1792. Two years later, he was appointed President of the Legislative Council of the Southwest Territory.[29]

Rutherford died in Sumner County, Tennessee, on August 10, 1805.[39]

Legacy

These areas are all namesakes of Griffith Rutherford:[17]

Footnotes

- MacDonald p. 11

- Ashe p. 381

- Wakelyn p. 176

- MacDonald p. 13

- MacDonald p. 21

- MacDonald p. 22

- Ashe p. 382

- MacDonald p. 20

- Clark p. 575

- MacDonald p. 28

- MacDonald p. 50

- MacDonald p. 55

- MacDonald p. 56

- Hunter p. 176

- Hunter p. 177

- "The Rutherford Expedition - North Carolina Digital History". www.learnnc.org. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- Wheeler p. 384

- "A report from the Rutherford Expedition - North Carolina Digital History". www.learnnc.org. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- Letter from Griffith Rutherford to Samuel Ashe; September 1, 1776; "Colonial and State Records of North Carolina;" University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; accessed January 2016

- MacDonald pp. 113–114

- MacDonald p. 118

- MacDonald p. 119

- MacDonald p. 121

- Lossing p. 597

- MacDonald p. 125

- Russell p. 154

- Harrison pp. 107–108

- Murray p. 50

- Hunter p. 178

- MacDonald p. 138

- MacDonald pp. 143–145

- MacDonald pp. 143–146

- MacDonald p. 147

- MacDonald pp. 151–152

- MacDonald p. 161

- MacDonald p. 168

- MacDonald p. 169

- MacDonald p. 176

- Macdonald p. 179

References

- Ashe, Samuel A'Court (1905). Biographical history of North Carolina from colonial times to the present, Volume 2. Greenboro: C. L. Van Noppen. OCLC 4243114.

- Clark, Walter (1886). The State Records of North Carolina, Volume 25. Goldsboro: Nash Brothers printing co. OCLC 1969836.

- Harrison, Henry William (1858). Battlefields and Naval Exploits of the United States: from Lexington to the City of Mexico. Philadelphia: H. C. Peck & T. Bliss. OCLC 9570227.

Battlefields and Naval Exploits of the United States: from Lexington to the City of Mexico.

- Hunter, C. L. (1877). Sketches of western North Carolina: Historical and Biographical. Raleigh: Raleigh News Steam Job Print. OCLC 1936249.

Sketches of western North Carolina: Historical and Biographical.

- Lossing, Benson John (1852). The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution. Manhattan: Harper & Bros. OCLC 638846585.

The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution.

- MacDonald, James M (2006). Politics of the Personal in the Old North State: Griffith Rutherford in Revolutionary North Carolina (PDF). ISBN 978-0-542-56459-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-23.

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern Colonies. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 9780786407835.

- Wakelyn, John L. (2004). Birth of the Bill of Rights: Major Writings. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313331954.

- Wheeler, John Hill (1851). Historical Sketches of North Carolina: from 1584 to 1851. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and Co. OCLC 221298491.

Historical Sketches of North Carolina: from 1584 to 1851.