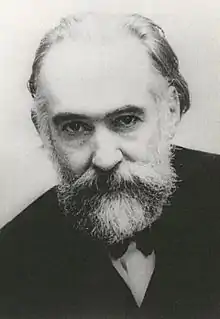

Gustave Guillaume

Gustave Guillaume (16 December 1883 – 3 February 1960),[1] was a French linguist and philologist, originator of the linguistic theory known as "psychomechanics".

Career

Guillaume was introduced to linguistics by the comparative grammarian Antoine Meillet, a student of Ferdinand de Saussure. He became well-versed in the historical and comparative method and adopted its mentalist tradition and systemic view of language. In his first major publication, Le problème de l’article et sa solution dans la langue française (The problem of the article and its solution in the French Language) (1919), Guillaume set out to apply the comparative method to the uses of the articles in Modern French, in order to describe their mental system located in the preconscious mind of the speaker rather than in pre-historical time. He was to pursue his research into the system of articles for the next 20 years.

In 1929, with Temps et Verbe, he described how the systems of aspect, mood and tense operate to produce an image of time proper to the event that is expressed by a verb in a sentence. This breakthrough gave him a first view of the mental system – the "psychosystem", as he later called it – of the verb and led him to realize that, as a part of speech, the verb is a system of systems that the speaker can use to construct a verb each time it is needed during the give-and-take of ordinary speech. From that point on in his career, he tried to analyze how words of different types are constructed – attempting to identify the grammatical systems involved in configuring a word's lexical importance, giving rise to the parts of speech observed in French and other Indo-European languages.

This led Guillaume to the conclusion that linguistics involves far more than analyzing how we understand what we hear and read. He decided that it was essential to adopt the point of view of the speaker, which would involve far more than pronouncing words and linking them together to form a sentence: "To study a language in circumstances as close as possible to the real circumstances of usage, one should, like a speaker, start with the language in a virtual state and trace how the speaker actualizes that virtuality."[2] In other words, before we speak a word to express the specific experience we have in mind, we must call on the mental potentialities acquired with our mother tongue to represent this experience by forming the word's meaning, both lexical and grammatical, and to actualize its physical sign. This realization confirmed his initial postulate that language consists of langue and discours, "language"and "speech", understood as an operative, potential-to-actual binary, and not as a static dichotomy like Saussure's langue and parole.

Guillaume's ongoing analysis of words led him to view each word type or part of speech as the means of incorporating certain syntactic possibilities into words themselves, to be deployed in the sentence. The challenge this poses for a linguist is to find the means of analyzing the preconscious mental operations, the "psychomechanisms" as he called them, giving rise to each part of speech. This in turn led him to examine languages where words are not formed in this way and in his last years to suggest the bases for a general theory of the word, or as he used to say, the vocable, to avoid the danger of foisting the Indo-European type of word onto languages of a very different type.

Writings

Throughout his teaching career, from 1938 to 1960 at the École pratique des hautes études, Guillaume wrote out his lectures, usually given twice a week. These, along with various research notes and essays, make up some 60,000 manuscript pages kept in the Fonds Gustave Guillaume at Laval University in Quebec City. To date, 20 volumes of these documents have been published (Presses de l'Université Laval). The only volume of Guillaume's writings translated into English is Foundations for a Science of Language, a series of excerpts from various lectures and essays, the first of which, from his inaugural lecture of 1952–1953, begins as follows:

"Science is founded on the insight that the world of appearances tells of hidden things, things which appearances reflect but do not resemble. One such insight is that what seems to be disorder in language hides an underlying order – a wonderful order. This observation is not mine – it comes from the great Meillet, who wrote that 'a language involves a system where everything fits together and has a wonderfully rigorous design.' This insight has been the guide and continues to be the guide of the studies pursued here."

Awards and recognition

Guillaume received the Prix Volney (Volney Prize) from for work in comparative philology in 1917.

The Association international de Psychomécanique du language (AIPL) organizes an international conference every three years for scholars influenced by Guillaume's approach to language.

Selected works

- Gustave Guillaume, Foundations for a Science of Language, John Benjamins: Amsterdam/Philadelphia, 1984.

See also

Notes

- Profile of Gustave Guillaume

- Temps et Verbe (1929), p. 121

References

- John Hewson, "Gustave Guillaume" in The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics,

2nd edition, ed. by Keith Brown, Vol. 5:169–170 (2004).

- Walter Hirtle, Language in the Mind, McGill-Queen's University Press: Montreal, (2007).

Further reading

- For a brief introduction to Guillaume's theory in English, see The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, and for a more lengthy introduction, see Language in the Mind.

- He heavily influenced the Welsh academic, Bobi Jones.