Ham Hill Hillfort

Ham Hill Hillfort is an Iron Age hillfort located on Ham Hill, Somerset, England. It was also occupied during the mesolithic and neolithic periods and later during Roman and medieval eras. The fort is a Scheduled Ancient Monument,[2] and the whole of the hill is a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest,[3] a country park operated by South Somerset Council, and is visited by over 250,000 people each year.[4]

| Ham Hill Hillfort | |

|---|---|

Looking east from the highest point of Hamdon Hill (on top of the inner rampart of the hillfort) towards the Stoke-sub-Hamdon war memorial which was unveiled in 1923 | |

| Location | Ham Hill, Somerset, England |

| Coordinates | 50°57′05″N 2°44′38″W |

| Area | 210 acres (85 ha) |

| Built | Iron Age |

| Reference no. | 1043362[1] |

Location of Ham Hill Hillfort in Somerset | |

It covers an area of 210 acres (85 ha), making it one of the largest hillforts in Britain.[5] It is the only one with a public house in its interior.[6]

Background

Hill forts developed in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age, at roughly the start of the first millennium BC.[7] The reason for their emergence in Britain, and their purpose, have been a subject of debate. It has been argued that they could have been military sites constructed in response to invasion from continental Europe, sites built by invaders, or a military reaction to social tensions caused by an increasing population and consequent pressure on agriculture. The dominant view since the 1960s has been that the increasing use of iron led to social changes in Britain. Deposits of iron ore were located in different places to the tin and copper ore necessary to make bronze; as a result, trading patterns shifted, the old elites lost their economic and social status, and power passed into the hands of a new group of people.[8] Archaeologist Barry Cunliffe believes that population increase still played a role and has stated, "[The forts] provided defensive possibilities for the community at those times when the stress [of an increasing population] burst out into open warfare. But I wouldn't see them as having been built because there was a state of war. They would be functional as defensive strongholds when there were tensions and undoubtedly some of them were attacked and destroyed, but this was not the only, or even the most significant, factor in their construction."[9]

Description

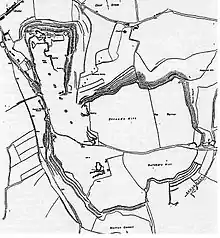

The hill rises to 400 feet (120 m) above sea level and towers over the surrounding Parrett and Yeo river valleys.[10] The 3 miles (5 km) ramparts enclose an area of 210 acres (85 ha).[11] The southern part is a rectangle approximately 800 metres (2,600 ft) by 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) with a northern spur 600 metres (2,000 ft) by 400 metres (1,300 ft) making an irregular L shape.[6]

Most of the perimeter is a double bank and ditch (multivallate), with some of the banks being up to 12 metres (39 ft) high. There is a major entrance to the south-east, on the line of the modern road, and another to the north-east, following a track from the Church of St Mary the Virgin at East Stoke in Stoke-sub-Hamdon.

History

The site was occupied during the mesolithic and neolithic periods,[2][12] and then by the Durotriges tribe,[11] from the 1st century BC.[13]

Archaeological finds, which date the original occupation to the 7th century BC,[6] include bronze-work, chariot parts, iron currency bars, gold and silver coins, cremations and burials.[5] A Glastonbury type pot has also been recovered.[6]

In 2013, excavations revealed some human skeletons and they may date to the first or second century AD. Tool marks on the bones suggest de-fleshing, reflecting both normal local funerary practices and violent episodes.[14][15]

The site was also important during the Roman era, with many finds indicating that there was a building on the site, possibly a Roman villa.[6][16][17] It may also have been the site of a fort that provided a point of control for the Fosse Way.[10] Roman coins, dating from the time of Domitian to Constantine the Great, were contained in a crock found during the 19th century. Other finds include a vessel containing 338 sestertii, which were given to the Museum of Somerset in 1915 by W. R. Phelps, and two other similar pots of coins that together contained slightly over 1,000 coins from Republican Rome to the time of Postumus, which must have been buried at some time after 260.[18] Damaged bronze scales of lorica squamata, a type of scale armour, have also been found.[19]

There is less evidence from the Saxon era, although the site might have been occupied during that period. It was definitely occupied during medieval times and was the site of the deserted hamlet of South Ameldon, which hosted an annual fair and court from 1102 until the 17th century.[6] In the 14th century part of the site was a rabbit warren.[10]

The site, particularly the northern and western areas, has been damaged by quarrying for Hamstone.[2][20] In the 1800s there were 24 small quarries operating on the hill employing some 200 men.[21] There are now two quarries, both owned by the Duchy of Cornwall, after whom the pub is named. A stone circle was added in 2000 to commemorate all those who have quarried stone on the site since Roman times.[22] It consists of 15 hamstones.[23]

References

- "Monument No. 1043362". National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Hamdon Hill Camp". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Ham Hill Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) citation sheet" (PDF). English Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2006. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- "Ham Hill Country Park". Visit Somerset. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- "Ham Hill Iron Age Hillfort Publisher=wessex archeology". Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- Adkins, Lesley; Rod Adkins (1992). A field guide to Somerset archaeology. Wimborne: Dovecote Press. pp. 72–74. ISBN 0-946159-94-7.

- Payne, Andrew; Corney, Mark; Cunliffe, Barry (2007). The Wessex Hillforts Project: Extensive Survey of Hillfort Interiors in Central Southern England. English Heritage. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-873592-85-4.

- Sharples, Niall M (1991). English Heritage Book of Maiden Castle. London: B. T. Batsford. pp. 71–72. ISBN 0-7134-6083-0.

- "Time Team: Swords, skulls and strongholds". Channel 4. 19 May 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dunning, Robert (1980). Somerset & Avon. Edinburgh: Bartholomew. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-7028-8380-8.

- "Ham Hill". Roman Britain.org. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- "Ham Hill Hillfort, S of Stoke sub Hamdon". Digital Digging. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- Dunning, Robert; A. P. Baggs; R. J. E. Bush; Margaret Tomlinson (1974). "Parishes: Montacute". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 3. British History Online. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- "Ham Hill fort dig reveals 2,500-year-old human remains". BBC Somerset. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- Alberge, Dalya (4 September 2013). "Slaughtered bodies stripped of their flesh - a gruesome glimpse of Iron-Age massacre at UK's largest hill fort. Hundreds if not thousands stripped of their flesh and chopped up, say archaeologists". The Independent. London. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- "Roman villa, Ham Hill, Stoke sub Hambdon". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- "Ham Hill geophysical survey area C (1992), Stoke sub Hamdon". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- "Roman occupation, Ham Hill, S of Stoke sub Hamdon". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- "Roman armour find, Ham Hill". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- "Ham Hill". Hillfort in England in Somerset. Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Medieval and Victorian History". Ham Hill Country Park. South Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- "Geology map". Visit Somerset. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- "Ham Hill, Somerset". Somersetian. Retrieved 6 February 2011.