Harmar campaign

The Harmar campaign was an Autumn 1790 attempt by the United States to subdue Native Americans nations in the Northwest Territory that were seen as hostile. The campaign was led by General Josiah Harmar, and is considered a significant campaign of the Northwest Indian War. The campaign ended with a series of battles from 19-21 October 1790 near the Miami villages of Kekionga. These were all overwhelming victories for the Native Americans, and are sometimes collectively referred to as Harmar's Defeat.

| Harmar campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Northwest Indian War | |||||||

General Josiah Harmar | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Western Confederacy |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Little Turtle (Miami) Blue Jacket (Shawnee) |

Josiah Harmar John Hardin | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| about 1,050 warriors |

320 regulars 1,100 militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| about 120-150 killed or wounded |

262 killed 106 wounded | ||||||

Prelude to battle

From 1784 to 1789, there was considerable violence between encroaching American settlers and the Shawnee and Miami Indians in Kentucky, along the Ohio River, and at the few American settlements north of the Ohio, with some 1,500 settlers killed by the Indians. However, there was no general war. Before the American Revolutionary War, the British had tried to preserve this area as a Native American reserve but it was forced to cede what became known as the Northwest Territory when the United States gained independence. American settlers were eager to enter these lands and started to do so.

In 1789, President George Washington wrote to Arthur St. Clair, Governor of the Northwest Territory (an entity not recognized by its Native inhabitants), and asked him to determine whether the Indians living along the Wabash and Illinois Rivers were "inclined for war or peace" with the United States. St. Clair decided the tribes "wanted war", and called for militia forces to be assembled at Fort Washington (now Cincinnati, Ohio) and Vincennes, Indiana. President Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox ordered General Josiah Harmar to lead these forces on a "punitive expedition" into the Shawnee and Miami lands as retaliation for the killings of American settlers and travellers on the contested frontier, and to deter the tribes from further attacks.

The primary objective of the campaign was the destruction of the large, main Miami village of Kekionga (present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana), where the St. Joseph and St. Mary's rivers join to form the Maumee River. St. Clair and Harmar also planned to build a fort there. But when St. Clair presented his plan to Washington at New York in August 1790, the President decided that a fort would be too vulnerable and too expensive.[2]

At this time, British forces still occupied Fort Detroit, in violation of the Treaty of Paris. St. Clair wrote to the British at Fort Detroit to assure them that the expedition was against only Indian tribes, and expressed his confidence that the British would not interfere.[3][4]

General Harmar gathered 320 regulars of the First American Regiment (organized into two battalions commanded by Major John Doughty and Major John Wyllys) and 1,133 militia from Kentucky and Pennsylvania, for a total of 1,453 men.[5] The force also had a battery of three horse-drawn 6-pounder cannons. Few experienced frontiersmen took part in the campaign; many instead paid recent immigrants to take their place. Lt. Ebenezer Denny wrote that the militia "appear to be raw and unused to the gun or the woods."[6] The troops were assembled in September, and the campaign had to be completed before winter set in. The pack horses which carried the troops' supplies were fed by grazing, and would starve on the frontier in winter. The Army had no time to train the militia.[5] The campaign was launched from Fort Washington on 7 October 1790, when General Harmar began the march north along the Great Miami River.

A smaller force led by Major Jean François Hamtramck marched north from Vincennes at the same time. Hamtramck commanded 330 soldiers of the First American Regiment and militia from Virginia.[7] He was to distract the Wabash Indians from the main force and then join Harmar for the main attack.[7] Hamtramck's force burned a few villages over 11 days, but was delayed when the militia refused to continue. Hamtramck returned to Vincennes instead of joining Harmar,[8] who, by 14 October, had marched to within 25 miles (40 km) of Kekionga. On that day, Kentucky scouts captured a Shawnee. After some intense interrogation, the Indian said that the Miami and Shawnee were gathering at Kekionga to meet Harmar's army.

Before dawn on 15 October, Harmar dispatched 600 men under Colonel John Hardin on a forced march to "surprise" the Indians at Kekionga. When Colonel Hardin's detachment reached Kekionga, they found the village abandoned. They burned it together with any stores they found, and camped south of the destroyed town.

Harmar reached other Miami villages near Kekionga on 17 October. The Miami had warning of the attack, and had evacuated their villages with as much food as they could carry. Some British-affiliated traders had been living among the Miami; they fled to Fort Detroit with their families and goods. They had distributed all available arms and ammunition to Miami warriors. The Miami were well informed of the size and movements of Harmar's force, and had learned of Harmar's inclination toward drunkenness.[9] The Americans seized the food left behind by the Miami.

Battle

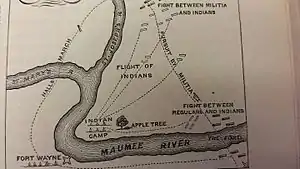

Battle of Heller's Corner

On 19 October, south of modern Churubusco, Indiana, Harmar sent out a scouting party under Colonel Hardin, consisting of 180 militia, a troop of cavalry under Major James Fontaine, and 30 regulars under Captain John Armstrong.[10][11] It was to estimate the strength of the Indians and attack the village of Chief Le Gris.[12] The party came within a few miles of Kekionga, where they encountered an Indian on horseback, who fled along a minor trail leading away from the village. Hardin ordered his force to pursue, but sent Major Fontaine's cavalry back to bring up a company that had been left behind. The Indian was a decoy, and led Hardin into a swampy lowland by the Eel River 13 miles northwest of Kekionga, where he could neither pursue nor easily retreat.

Indians led by Little Turtle attacked Hardin's force from three sides. Most of the militia fled, warning Major Fontaine's cavalry to get out.

The regulars stood their ground with some of the militia. Only 8 of the 30 regulars survived. 40 militia were killed,[13] and 12 Americans were wounded.[14] Captain Armstrong hid in the marsh and escaped with his life. He blamed Hardin and the militia for the defeat, and claimed that only about 100 Indians had been involved. This was the approximate number of warriors available from Kekionga and Le Gris' village.[15] The battle is sometimes referred to as Hardin's defeat.[9][16]

Hartshorn's defeat

On 20 October, General Harmar arrived at the camp outside Kekionga. He sent a detachment of 300 men under Ensign Phillip Hartshorn northward to scout for Indian movements. Eight miles north of Kekionga, Hartshorn was ambushed by a large Indian force, which killed him and 19 of his men. Instead of advancing immediately to attack the Indians, Harmar pulled back several miles south of Kekionga. He did not arrange for a burial detail to bury the twenty dead. Morale had plummeted, and the men were enraged at the cowardice of their commander. Hardin demanded that he be allowed to attack the Indians with 400 men, or at the very least, bury their fallen comrades.

Battle of the Pumpkin Fields

On the night of 21 October, Colonel Hardin advanced with 300 militia and 60 regulars of the First American Regiment, under Major John P. Wyllys. At dawn on 22 October, they found about 1,000 Indians encamped at Kekionga. Hardin immediately sent to Harmar requesting reinforcements. When the courier told Harmar (who was rumored to have been drunk) about the size of the enemy force, he became visibly shaken. He ordered his 800-900 remaining men into a hollow defensive square and refused to come to Hardin's aid, leaving him alone to face an enemy more than twice his number. Colonel Hardin, expecting reinforcements at any time, divided his command into four groups under Major Wyllys, Major Hall, Major Fontaine, and Major McMullen. He planned to flank the Indians on all sides.[17]

The Indians at Kekionga, who were led by Little Turtle, attacked first, however. Little Turtle sent small parties to fire on the militia and retreat. The militia gave chase in many instances, until the regulars were left isolated. Little Turtle then attacked Major Wyllys's detachment, with results as devastating as at Heller's Corner on 19 October.[18] Major Fontaine, meanwhile, led a cavalry charge into a wooded area and was ambushed. Soon the Shawnee and Miami attacked Hardin from three sides. Still expecting reinforcements from Harmar, Hardin's men put up a valiant defense, holding the Indians at bay for over three hours before finally falling back to join the rest of the army.[19]

This battle, sometimes known as Harmar's defeat by the Americans, was called the Battle of the Pumpkin Fields by the Indians, because the steam from the scalped skulls reminded the Indians of squash steaming in the autumn air. 180 American men were either killed or wounded.[13] The army forces reported 129 men killed in action (14 officers, including Major Wyllys and Major Fontaine, and 115 enlisted men) and 94 wounded (including 50 of the Regulars). Estimates of Indian casualties range from 120 to 150 total.

Aftermath

After such high casualties from these engagements, General Harmar determined that he could not attack. The approaching winter further threatened his command, as militia deserted and horses starved. The retreating force reached Fort Washington on 3 November 1790.[13]

It was the worst defeat of U.S. forces by Indians up to that time. It was later surpassed only by St. Clair's Defeat in this war, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn in the late 19th century in the West.[20] Little Turtle became established as an Indian hero, and the Indians in the Northwest Territory took heart to continue to resist the United States.[21] Indians attacked settlements all across the Northwest Territory, including the January 1791 Big Bottom massacre and Siege of Dunlap's Station.[22]

President Washington was furious at the news of the defeat,[21] and lamented "my mind... is prepared for the worst; that is, for expence without honor or profit."[8] He and St. Clair feared that the campaign would embolden the confederacy.[23] Senator William Maclay wrote "A war has actually been undertaken against the Wabash Indians without any authority of Congress."[24] That December, General Von Steuben wrote to Alexander Hamilton, lamenting the loss of Major John Wyllys and expressing fear for Major Hamtramck. "This war is not over, it is only the Commencement of the Hostilities, so will we never learn to be wise that by force of stupidity?"[25]

A court martial in 1791 cleared Harmar of any wrongdoing during the campaign.[26][27]

Learning of the defeats, Congress raised a second regiment of Regular soldiers for six months, but it later reduced the soldiers' pay. The First Regiment was soon reduced to 299 soldiers, while the new Second Regiment recruited only half of their authorized number.[21] When Governor St. Clair led a similar expedition the next year, he had to call out the militia to meet the required manpower. His campaign would end in St. Clair's Defeat, the worst defeat suffered by the U.S. Army from Native Americans.

References

Notes

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 43.

- Schecter, 232

- Barnhart, pp 284-285, fn.21

- Washington, as early as 1784, had told Henry Knox that a strong U.S. post should be established at Kekionga. St. Clair, in 1790, had told both Washington and Knox that "we will never have peace with the Western Nations until we have a garrison there." Knox, however, was concerned that a U.S. fort at Kekionga would provoke the Indians and denied St. Clair's request to build a fort there. Following Harmar's defeat, Knox changed his mind. He instructed St. Clair to occupy and fortify Kekionga the following year. Poinsatte, 21-23

- Barnhart 1971, p. 283.

- Winkler, 25

- Stewart 2009, p. 118.

- Schecter, 233

- Poinsatte, 22

- Winkler, 15

- Pfingsten, Bill, ed. (22 September 2011). "Site of Hardin's Defeat". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- Carter, 94

- Barnhart 1971, p. 284.

- Allison, 73

- Carter, 92-93

- "IHB: Site of Hardin's Defeat". www.in.gov. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Allison, 74

- Allison, 75

- Map of "Harmar's Defeat", Kentucky History Archived 10 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Allison, 76

- Fleming, Thomas (August 2009). "Fallen Timbers, Broken Alliance". Military History. History Reference Center, EBSCOhost. 26 (3): 36–43.

- Winkler, John F (2011). Wabash 1791. St. Clair's defeat. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-84908-676-9.

- Wingate, Christopher W (2013). Military Professionalism and the Early American Officer Corps, 1789-1796 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 6. LCCN 2013038283. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- Calloway, Colin G (2018). The Indian World of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 385. ISBN 9780190652166. LCCN 2017028686.

- Steuben, Friedrich. "To Alexander Hamilton from Baron von Steuben, 16 December 1790". Founders Online, National Archives (in French). Retrieved 16 October 2020.

Je crain encore pour Hamtromac.3 Cette guerre n’est pas finis, ce ne sont que les Commencemens des Hostilities, n’apprendrons nous donc jamais d’etre sage qu’a force de balourdise?

- Johnson, Jeffery L. (October 2004). "Saving Private Boon: Joseph Boone at "Harmar's Defeat"". Compass. The Boon Society. Archived from the original on 28 December 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "Harmar's Defeat". Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

Sources

- Allison, Harold (1986). The Tragic Saga of the Indiana Indians. Turner Publishing Company, Paducah. ISBN 0-938021-07-9.

- Barnhart, John D; Riker, Dorothy L (1971). Indiana to 1816. The Colonial Period. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 0-87195-109-6.

- Carter, Harvey Lewis (1987). The Life and Times of Little Turtle: First Sagamore of the Wabash. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-01318-2.

- Johnson, Jeffery L (2004). Saving Private Boon: Joseph Boone at "Harmar's Defeat. Compass. The Boon Society.

- Poinsatte, Charles (1976). Outpost in the Wilderness: Fort Wayne, 1706-1828. Allen County, Fort Wayne Historical Society.

- Stewart, Richard W, ed. (2009). American Military History Volume 1. The United States Army and the Forging of a Nation, 1775-1917 (PDF) (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 978-0-16-072362-9.

- Schecter, Barnet (2010). George Washington's America. A Biography Through His Maps. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1748-1.

- Winkler, John F. (2011). Wabash 1791: St. Clair's Defeat; Osprey Campaign Series #240. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-676-9.