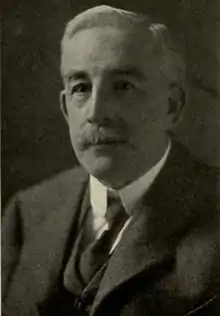

Henry Leffmann

Henry Leffmann (September 9, 1847 - December 25, 1930) was an American chemist, physician and writer.

Henry Leffmann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 9, 1847 |

| Died | December 25, 1930 |

| Occupation | Chemist, physician |

Biography

Leffmann born in Philadelphia.[1] He was the fourth son of Henry Leffmann, a German Jew and Sarah Ann Paul of Doylestown a Quaker of Welsh ancestry.[1][2]

In 1864 he became a chemical laboratory assistant at Philadelphia High School.[2] He was assistant to Benjamin H. Rand at Jefferson Medical College (1865-1870). He obtained his M.D. in 1869 from Jefferson Medical College.[2] Leffmann was chemist to the coroner of Philadelphia (1875-1880) and district attorney (1885-1897).[1] He was a chemist to dairy and food commissioners of Pennsylvania. He married Fannie Frank in 1876, they had no children.[1][3]

Leffmann was lecturer on Toxicology at Jefferson College (1870-1882), lecturer on botany at Wagner Free Institute of Science (1874-1875) and Professor of Chemistry (1885-1903).[2] He was microscopist of Pennsylvania State Board of Agriculture (1877-1905), professor of chemistry at Philadelphia Polyclinic (1883-1898) and pathological chemist at Jefferson Medical College Hospital (1887-1905).[2] He received an honorary Ph.D from the Wagner Free Institute of Science in 1874 and a DDS from Philadelphia College of Dental Surgery in 1884.[2]

Leffmann supported women's rights and has been cited as an "early male medical pro-feminist".[4] He was professor of chemistry at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (1890-1917) and emeritus until 1923.[5] Leffmann was not religious and joined the Society for Ethical Culture.[5]

Criticism of Christianity

Leffmann authored a pamphlet The Mental Condition and Career of Jesus of Nazareth in 1904. He argued that Jesus was a megalomaniac and that much of his phenomena could be explained by hypnosis and suggestion. Leffmann was an advocate of the swoon hypothesis, arguing that Jesus did not die on the cross, but was "tenderly cared for, probably by the mother and brothers whom he had disowned and scorned, and quietly buried after his death, which may have occurred very soon afterwards."[6]

Selected publications

- Memoranda on Poisons (1878)

- First Step in Chemical Principles (1879)

- A Compend of Chemistry, Inorganic and Organic (1891)

- Select Methods in Food Analysis (with William Beam, 1901)

- The Mental Condition and Career of Jesus of Nazareth Examined in the Light of Modern Knowledge (1904)

- Analysis of Milk and Milk Products (1905)

- Outline Autobiography of Henry Leffmann (1905)

- About Dickens (1908)

- The States-Rights Fetish: A Plea for Real Nationalism (1913)

- Examination of Water for Sanitary and Technic Purposes (1915)

References

- White, James Terry. (1936). The National Cyclopædia of American Biography, Volume 25. New York: J. T. White & Company. pp. 158-159

- England, Joseph W. (1922). The First Century of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1821-1921. Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science. pp. 429-430

- Malone, Dumas. (1933). Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 142-143

- Peitzman, Steven J. (2003). "Why Support a Women's Medical College? Philadelphia's Early Male Medical Pro-Feminists". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 77 (3): 576–599.

- Peitzman, Steven Jay. (2000). A New and Untried Course: Woman's Medical College and Medical College of Pennsylvania, 1850-1998. Rutgers University Press. pp. 86-88. ISBN 0-8135-2815-1

- Leffmann, Henry. (1904). The Mental Condition and Career of Jesus of Nazareth Examined in the Light of Modern Knowledge. Philadelphia. p. 21

External links

- Henry Leffmann (Online Books)