Hermann Oberth

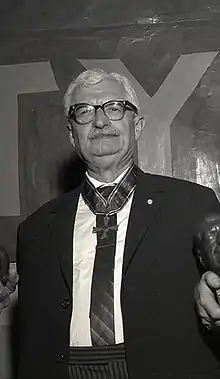

Hermann Julius Oberth (German: [ˈhɛrman ˈjuːli̯ʊs ˈoːbɛrt]; 25 June 1894 – 28 December 1989) was an Austro-Hungarian-born German physicist and engineer. He is considered one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics, along with the French Robert Esnault-Pelterie, the Russian Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, and the American Robert Goddard.[4][5]

Hermann Oberth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Hermann Julius Oberth 25 June 1894 Nagyszeben, Austria-Hungary (today Sibiu, Romania) |

| Died | 28 December 1989 (aged 95) |

| Nationality | German |

| Citizenship | Hungarian, German[1] |

| Alma mater | University of Cluj |

| Awards | Prix REP-Hirsch, 1929; Wilhelm Exner Medal 1969[2] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronautics and physics |

| Doctoral advisor | Augustin Maior |

| Notable students | Wernher von Braun[3] |

Early life

Oberth was born to a Transylvanian Saxon family in Nagyszeben (Hermannstadt), Kingdom of Hungary (today Sibiu in Romania).[6] At the age of 11 years, Oberth's interest in rocketry was set off by the novels of Jules Verne, especially From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon. He was fond of reading over them up until they were engraved on his memory.[7] As a result, Oberth constructed his first model rocket as a school student at the age of 14. In his youthful experiments, he arrived independently at the concept of the multistage rocket. However, during this time, he lacked the resources to put his ideas into practice.

In 1912, Oberth began the study of medicine in Munich, Germany, but at the outbreak of World War I, he was drafted into the Imperial German Army, assigned to an infantry battalion, and sent to the Eastern Front against Russia. In 1915, Oberth was moved into a medical unit at a hospital in Segesvár (German Schäßburg, Romanian Sighișoara), Transylvania, in Austria-Hungary (today Romania).[8] There he found the spare time to conduct a series of experiments concerning weightlessness, and later resumed his rocketry designs. By 1917, he showed designs of a missile using liquid propellant with a range of 290 km to Hermann von Stein, the Prussian Minister of War.[9]

On 6 July 1918, Oberth married Mathilde Hummel, with whom he had four children. Among these were a son who died as a soldier in World War II, and a daughter who also died during the war when there was an accidental explosion at a liquid oxygen plant where she was in August 1944. In 1919, Oberth once again moved to Germany, this time to study physics, initially in Munich and later at the University of Göttingen.

In 1922, Oberth's proposed doctoral dissertation on rocket science was rejected as "utopian". He next had his 92-page work published privately in June 1923 as the somewhat controversial book, Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen ("The Rocket into Planetary Space"). By 1929, Oberth had expanded this work to a 429-page book titled Wege zur Raumschiffahrt ("Ways to Spaceflight"). Oberth commented later that he made the deliberate choice not to write another doctoral dissertation. He wrote, "I refrained from writing another one, thinking to myself: Never mind, I will prove that I am able to become a greater scientist than some of you, even without the title of Doctor."[10] Oberth criticized the German system of education, saying "Our educational system is like an automobile which has strong rear lights, brightly illuminating the past. But looking forward, things are barely discernible."[10] Hermann Oberth was finally awarded his licence[11] in physics with the same rocketry paper that he had written before, by the University of Cluj, Romania, under professor Augustin Maior, on 23 May 1923.[8]

Oberth became a member of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR) – the "Spaceflight Society" – an amateur rocketry group that had taken great inspiration from his book, and Oberth acted as something of a mentor to the enthusiasts who joined the Society. Oberth lacked the opportunities to work or to teach at the college or university level, as did many well-educated experts in the physical sciences and engineering in the time period of the 1920s through the 1930s – with the situation becoming much worse during the worldwide Great Depression that started in 1929. Therefore, from 1924 through 1938, Oberth supported himself and his family by teaching physics and mathematics at the Stephan Ludwig Roth High School in Mediaș, Romania.[8]

Rocketry and space flight

In parts of 1928 and 1929, Oberth also worked in Berlin as a scientific consultant on the film, Frau im Mond ("The Woman in the Moon"), which was directed and produced by the great film pioneer Fritz Lang at the Universum Film AG company. This film was of enormous value in popularizing the ideas of rocketry and space exploration. One of Oberth's main assignments was to build and launch a rocket as a publicity event just before the film's premiere. He also designed the model of the Friede, the main rocket portrayed in the film.

On 5 June 1929, Oberth won the first (Robert Esnault-Pelterie - André-Louis Hirsch) Prix REP-Hirsch of the French Astronomical Society for the encouragement of astronautics in his book Wege zur Raumschiffahrt ("Ways to Spaceflight") that had expanded Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen to a full-length book.[12] The book [13] is dedicated to Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou.[14]

In the autumn of 1929, Oberth conducted a static firing of his first liquid-fueled rocket motor, which he named the Kegeldüse. The engine was built by Klaus Riedel in a workshop space provided by the Reich Institution of Chemical Technology, and although it lacked a cooling system, it did run briefly.[15] He was helped in this experiment by an 18-year-old student Wernher von Braun, who would later become a giant in both German and American rocket engineering from the 1940s onward, culminating with the gigantic Saturn V rockets that made it possible for man to land on the Moon in 1969 and in several following years. Indeed, Von Braun said of him:

Hermann Oberth was the first, who when thinking about the possibility of spaceships grabbed a slide-rule and presented mathematically analyzed concepts and designs.... I, myself, owe to him not only the guiding-star of my life, but also my first contact with the theoretical and practical aspects of rocketry and space travel. A place of honor should be reserved in the history of science and technology for his ground-breaking contributions in the field of astronautics.[3]

In 1938, the Oberth family left Sibiu, Romania, for good, to first settle in Austria, then in Nazi Germany, then in the United States, and finally back to a democratic West Germany. Oberth himself moved on first to the Technische Hochschule in Vienna, Austria, then to the Technische Hochschule in Dresden, Germany. (A Technische Hochschule at that time was a technical college offering advanced professional training in selected fields, rather than an institution also engaged in basic research as a university.)

Oberth moved to Peenemünde, Germany, in 1941 to work on the Aggregat rocket program. Around September 1943, he was awarded the Kriegsverdienstkreuz I Klasse mit Schwertern (War Merit Cross 1st Class, with Swords) for his "outstanding, courageous behavior ... during the attack" on Peenemünde by Operation Hydra, part of Operation Crossbow.[16]

Later he worked on solid-propellant anti-aircraft rockets at the German WASAG military organization near Wittenberg. Around the end of World War II in Europe, the Oberth family moved to the town of Feucht, near the regional capital of Nuremberg, which became part of the American Zone of occupied Germany, and also the location of the high-level war-crimes trials of the surviving Nazi leaders. Oberth was allowed to leave Nuremberg to move to Switzerland in 1948, where he worked as an independent consultant and a writer.

In 1950, Oberth moved on to Italy, where he completed some of the work that he had begun at the WASAG organization for the new Italian Navy. In 1953, Oberth returned to Feucht, Germany, to publish his book Menschen im Weltraum (Mankind into Space), in which he described his ideas for space-based reflecting telescopes, space stations, electric-powered spaceships, and space suits.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Oberth offered his opinions regarding unidentified flying objects (UFOs). He was a supporter of the extraterrestrial hypothesis for the origin of the UFOs that were seen from Earth. For example, in an article in The American Weekly magazine of 24 October 1954, Oberth stated, "It is my thesis that flying saucers are real, and that they are space ships from another solar system. I think that they possibly are manned by intelligent observers who are members of a race that may have been investigating our earth for centuries..." [17] He also wrote an article in the second edition of Flying Saucer Review titled "They Come From Outer Space". He discussed the history of reports of "strange luminous objects" in the sky, mentioning that the earliest historical case is of "Shining Shields" reported by Pliny the Elder. He wrote, "Having weighed all the pros and cons, I find the explanation of flying discs from outer space the most likely one. I call this the "Uraniden" hypothesis, because from our viewpoint the hypothetical beings appear to come from the sky (Greek – 'Uranos')." [18]

Oberth eventually came to work for his former student, Wernher von Braun, who was developing space rockets for NASA in Huntsville, Alabama. (See also List of German rocket scientists in the United States.) Among other things, Oberth was involved in writing the study, The Development of Space Technology in the Next Ten Years. In 1958, Oberth was back in Feucht, Germany, where he published his ideas on a lunar exploration vehicle, a "lunar catapult", and on "muffled" helicopters and airplanes. In 1960, back in the United States again, Oberth went to work for the Convair Corporation as a technical consultant on the Atlas rocket program.

Later life

Oberth retired in 1962 at the age of 68. From 1965 to 1967 he was a member of the National Democratic Party of Germany, which was considered to be far right. In July 1969, Oberth returned to the United States to witness the launch of the Apollo project Saturn V rocket from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida that carried the Apollo 11 crew on the first landing mission to the Moon.[19]

The 1973 oil crisis inspired Oberth to look into alternative energy sources, including a plan for a wind power station that could utilize the jet stream. However, his primary interest during his retirement years was to turn to more abstract philosophical questions. Most notable among his several books from this period is Primer For Those Who Would Govern.

Oberth returned to the United States to view the launch of STS-61-A, the Space Shuttle Challenger launched 30 October 1985.

Oberth died in Nuremberg, West Germany, on 28 December 1989, just shortly after the fall of the Iron Curtain that had for so long divided Germany into two countries.[9][20]

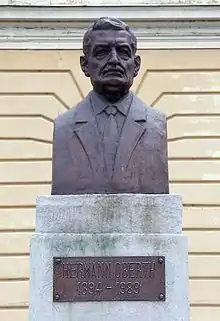

Legacy

Hermann Oberth is memorialized by the Hermann Oberth Space Travel Museum in Feucht, Germany, and by the Hermann Oberth Society. The museum brings together scientists, researchers, engineers, and astronauts from the East and the West to carry on his work in rocketry and space exploration.

He discovered the Oberth effect, in which a rocket engine when traveling at high speed generates more useful energy than one travelling at low speed.

In 1980, Oberth was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[21]

There is also a crater on the Moon and asteroid 9253 Oberth named after him.

The Danish Astronautical Society has named Hermann Oberth an honorary member.[22]

The Faculty of Engineering of Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu is named after him.[23]

In Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, the USS Grissom was classified as an Oberth-class starship. Several other Oberth-class starships also appeared in subsequent Star Trek films and television series.

Books

- Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (1923) (By Rocket into Planetary Space) (in German) OCLC 6026491

- Ways to Spaceflight (1929) OCLC 255256956

- The Moon Car (1959) OCLC 574140

- The Electric Spaceship (1960) OCLC 20586236

- Primer for Those Who Would Govern (1987) ISBN 0-914301-06-3

- Georgiy Stepanovich Vetrov, S. P. Korolyov and space. First steps. — 1994 M. Nauka, ISBN 5-02-000214-3.

- S. P. Korolev. Encyclopedia of life and creativity" – edited by C. A. Lopota, RSC Energia. S. P. Korolev, 2014 ISBN 978-5-906674-04-3

See also

References

- Horia-Nicolai Teodorescu, "Hermann Oberth And His Professional Geography in the European Context of the 20th Century" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2009. (261 KB)

- Editor, ÖGV. (2015). Wilhelm Exner Medal. Austrian Trade Association. ÖGV. Austria.

- Hermann Oberth Raumfahrt Museum. Oberth-museum.org (1989-12-28). Retrieved on 2015-06-27.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Angelo, Joseph E. (2003). Space Technology. Greenwood Press. p. 70. ISBN 1-57356-335-8.

- Winter, Frank (1990). Rockets Into Space. pp. 18. ISBN 0674776607.

- Ianzer, Jürgen Heinz. "Hermann Oberth, pǎrintele zborului cosmic" [Hermann Oberth, Father of the Cosmic Flight] (PDF) (in Romanian). pp. 3, 11, 13, 15.

- Mort de Hermann Oberth, pionnier de la conquête spatiale ("The Death of Hermann Oberth, Space Conquest Pioneer"), in Le Monde, 1 January 1990, pp. 3, 16, accessed on 7 October 2006.

- "Hermann Oberth, Father of Space Travel", at. Kiosek.com (29 December 1989). Retrieved on 2015-06-27.

- Augustin Maior. 19 October 2016.

- L'Aerophile, 1–15 June 1929, p.176; L. Blosset, Smithsonian Annals of Flight, No. 10, p. 11

- Oberth, Hermann (1970) [1929]. Ways to Spaceflight. NASA. Retrieved 21 December 2017 – via archive.org.

- "From "The Rocket in Interplanetary Space" to "Frau im Mond" (June 1923 – 1929)". HistoryofInformation.com. Jeremy Norman & Co., Inc. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- Neufeld, Michael J. (1996). The Rocket and the Reich. Harvard University Press. ISBN 067477650X.

- Ordway, Frederick I., III. The Rocket Team. Apogee Books Space Series 36. p. 36.

- Schuessler, John L., "Statements about Flying Saucers and Extraterrestrial Life Made by Prof. Hermann Oberth, German Rocket Scientist" 2002 Archived 25 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine; for example, the American Weekly article also appeared in the Washington Post and Times Herald, pg. AW4, and Milwaukee Sentinel

- Hermann Oberth "They Come From Outer Space" Flying Saucer Review Volume 1 Number 2, May–June 1955 pp. 12–14

- "Hermann Oberth" Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, at the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission

- "Hermann Oberth, 95, German Rocket Expert". The New York Times. 31 December 1989. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

Hermann Julius Oberth, a pioneer of the space age who worked with Werner von Braun to help develop Germany's V-2 rocket, died on Friday. He was 95 years old. Mr. Oberth died at a hospital in Nuremberg after a short illness, the Hermann Oberth Museum in Feucht said in a statement.

- Sprekelmeyer, Linda, editor. These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame. Donning Co. Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57864-397-4.

- Official Website of the Danish Astronautical Society Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Rumfart.dk. Retrieved on 27 June 2015.

- "Acasă – Facultatea de Inginerie". Inginerie.ulbsibiu.ro. Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu. 20 June 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hermann Oberth. |