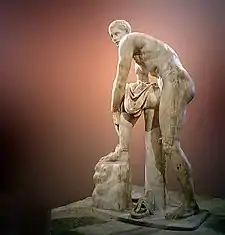

Hermes Fastening his Sandal

The sculptures of Hermes Fastening his Sandal, which exist in several versions, are all Roman marble copies of a lost Greek bronze original in the manner of Lysippos, dating to the fourth century BCE. The identity of the subject, which may simply represent an idealized athlete, is conventional. No attribute in any of the surviving examples clearly identifies Hermes, who wears neither hat nor helmet; none of the surviving original sandals are represented as winged. A pair of sandals figures in the myth of Theseus, and when the painter-dealer Gavin Hamilton uncovered an example in the swamp ground called the Pantanello at Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli in 1769, he hesitated between calling it a Theseus or a Cincinnatus. Jason's myth also involves a lost sandal.[1] When Augustus Hare saw that sculpture in the Ball Room of Lansdowne House (the Earl of Shelburne having been created Marquess of Lansdowne in 1784), in Berkeley Square, he noted it as "Jason fastening his sandal."[2]

The identification with Hermes is based on an identification of the original bronze model as a sculpture of Hermes in the gymnasium and thermae of Zeuxippos in Constantinople, which was described in detail by Christodoros of Koptos in his ekphrasis of the gymnasium as it still remained in Late Antiquity:

There was Hermes, of the golden wand. He stood and fastened up the thongs of his winged sandal with his right hand, yearning to rush forth upon his course. His swift right leg was bent at the knee, and on it he rested his left hand, and meanwhile he was turning his face up to heaven, as if he were hearing the commands of his king and father"[3]

Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway prefers to call the subject The Sandal-Binder or Jason;[4] she notes, that, from the finding sites, the sculpture appears to have been popular in gardens and gymnasia.

Judging from the fully lifesize scale of the copies and their generally high quality, the original bronze must have been respected as one of the received masterpieces in the canon of antiquity (Ridgeway 1964:120). Three moderately complete Roman marble copies have survived.

- The Louvre Hermes Fastening his Sandal[5] (illustration) was the first to be discovered. Haskell and Penny[6] note that an engraving of it was published in 1594, where it was described as the property of Alessandro Peretti Cardinal di Montalto and was doubtless already in the Villa Peretti di Montalto, which the very young Cardinal's uncle Pope Sixtus V, had recently built; it was recorded there in 1655, when the villa was inherited from the Peretti di Montalto heirs by prince Savelli; it was bought for Louis XIV in 1685 and kept at the Château of Versailles until 1792, when it passed to the recently established museum in the Louvre. It was formerly restored with a plowshare in order to illustrate Cincinnatus receiving the delegation from the Roman Senate, an impossible subject for a heroic sculpture; as Winckelmann pointed out, its heroic nudity would have been incongruous.[7] It has been divested of its accretion. The sculpture is of Pentelic marble, the antique head of Parian marble.

- The Lansdowne Sandal Binder (marble, 1.54m.), found in Gavin Hamilton's excavations in 1769 at the site of Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli, was offered to Pope Clement XIV who refused it, and sold in 1772 to the Earl of Shelburne;[8] it was sold in 1930 and is now at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, where Poulsen described it as probably Hermes, leaving open the possibility that it simply portrays an athlete.[9] This is the only surviving model that has retained its head, though the head has been broken.

- The Munich Sandal-Fastener in the Glyptothek, Munich, was found in the late 1780s by conte G. Campagnoli Marefoschi, in his own grounds on the site of part of Hadrian's Villa; Thomas Jenkins, the English dealer established at Rome, sold it to duca Luigi Braschi Onesti, who had it further restored by Francesco Antonio Franzoni, before selling it to Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria. This version shows the second sandal on the ground; other sculptures have been restored with this detail. (Ridgeway 1964:114 and note 11) It has been restored with an unrelated head and has been thoroughly resurfaced. A plaster cast incorporating the features that are original in each of these versions is conserved in the Glytothek, Munich; a bronze casting of it is in the Stadtmuseum, Stettin (Ridgeway 1964:117)

Three surviving torsos have also been identified, including one in unfinished state, which has retained its head and has escaped the eighteenth-century Roman restorers; it is now conserved at the Acropolis Museum, Athens. Other variants include sculptures in similar, but reversed mirror-image poses, probably intended as pendants to the Hermes Fastening his Sandal.

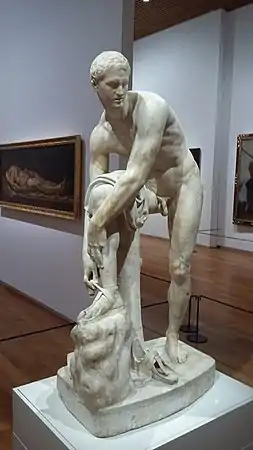

The theme was taken up by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle in 1744, and by François Rude, who showed at the Paris salon of 1828 a Mercury Fastening his Sandal in plaster. Rude's god instead shows the influence of Giambologna’s famous Mercury (c. 1580; Florence, Bargello)

Gallery

The Louvre copy on exhibit at the Musée Matisse (Le Cateau)

The Louvre copy on exhibit at the Musée Matisse (Le Cateau) View from the back

View from the back Hermes Sandalbinder from Hadrian's Villa now at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Hermes Sandalbinder from Hadrian's Villa now at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.jpg.webp) Copy at the Copenhagen Botanical Gardens

Copy at the Copenhagen Botanical Gardens_(auto_contrast).jpg.webp) Variant from Hadrian's Villa now at the Capitoline Museums

Variant from Hadrian's Villa now at the Capitoline Museums

Notes

- Jason's appearance before king Pelias with one sandal, having lost the other in crossing a river, appeared to satisfy an ominous oracle for the king, who sent Jason on his quest as a means of ridding himself of this dangerous interloper.

- Augustus John Cuthbert Hare, Walks in London: "Lansdowne House" (New York: G. Routledge, 1878) vol. II p 85; the identification as Jason had been put forward by Winckelmann

- Quoted by A. H. Smith, "The Sculptures in Lansdowne House" The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 6 No. 22 (January 1905) p. 277.

- Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway, "The Date of the So-Called Lysippean Jason" American Journal of Archaeology 68.2 (April 1964:113-128)

- Ma 83. 1.61 m.. Louvre Atlas database.

- Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Antique Sculpture 1500-1900 (Yale University Press) 1981, cat. 83, pp 182-84; Haskell and Penny's account of its history is followed in this article.

- Noted by Haskell and Penny 1981:

- Haskell and Penny 1981:184;G. J. Hamilton and A. H. Smith, "Gavin Hamilton's Letters to Charles Townley" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 21 (1901:306-321) p. 319: "A Theseus putting on his Sandal...Lord Shelburne"; "Cincinnatus" added

- F. Poulsen, Catalogue of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, 1951:204; Copenhagen I.N.2798, height 1.45m; the collection also has a plaster cast (A7) of the Louvre marble.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sandalbinder. |

- Hare, Augustus John Cuthbert (1878). Walks in London. Vol. 2, p. 185. London: Daldy, Isbister. Title page at HathiTrust.

- Hamilton, G. J.; A. H. Smith (1901). "Gavin Hamilton's Letters to Charles Townley", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 21, pp. 306–321. JSTOR 623878.

- Haskell, Francis; Nicholas Penny (1981). "23. Cincinnatus", pp. 182–186 and Fig. 95, in Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900. New Haven: Yale University Press. Limited search copy at HathiTrust. OCLC 853500647.

- Poulsen, Frederik (1951). Catalogue of ancient sculpture in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Copenhagen: Nielsen & Lydiche. Limited search copy at HathiTrust. OCLC 3657489.

- Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo (1964). "The Date of the So-called Lysippean Jason", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 66, no. 2 (April), pp. 113–126. JSTOR 501650.

- Smith, A. H. (1905). "The Sculptures in Lansdowne House", The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 6., no. 22 (January), pp. 264–277. JSTOR 856224.

- Winkelmann, Giovanni (1783). Storia delle arti disegno presso gli antichi, translated from German and in this edition, corrected and augmented by Abbot Carlo Fea, vol. 2, pp. 327–328. Rome: Pagliarini.