Higashiyama culture

The Higashiyama culture (東山文化 Higashiyama bunka) is a segment of Japanese culture originated and promoted in the 15th century by the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, after he retired to his villa in the eastern hills (東山 Higashiyama) of the capital city Kyoto.

History

Based largely on the ideals and aesthetics of Zen Buddhism and the concept of wabi-sabi, Higashiyama culture centered on the development of chadō (Japanese tea ceremony), ikebana (flower arranging), Noh drama, and sumi-e ink painting. Much of what is commonly seen today as traditional Japanese culture originated or developed in this period. Higashiyama culture is often contrasted with Kitayama bunka (北山文化), the "Kitayama Culture" from earlier in the Muromachi period. In this comparison Kinkaku-ji, representative of Kitayama culture is compared with Ginkaku-ji, representative of Higashiyama culture.

Yoshimasa's retirement villa was turned into the temple Ginkaku-ji (the Temple of the Silver Pavilion) after his death. It is situated in Kyoto's Sakyō-ku, and was the center of the Higashiyama cultural outgrowth in a number of ways. The Pavilion is revered for its simple beauty, the silver having never been added. The rock garden next to it is likewise one of the most famous in Japan, and praised for its Zen and wabi-sabi aesthetics. It is a quintessential example of the idea that only the trained expert should be able to recognize the subtle beauty within art and architecture; the beauty of the object should not be underscored and emphasized, but gently hidden. The retired shogun also invited many artists, poets, and court nobles to his villa, encouraging the development of their arts. A vast and priceless collection of artifacts came together, which was known as the Higashiyama Treasure.

The Tōgudō building includes a shoin-style room called the Dōjinsai. It originally had a fireplace built into the floor, and due to this, the Dōjinsai is considered the earliest extant example of a room designed for use as a tea room.[1]

There were many architectural innovations in this period, exhibited in the Ginkaku-ji in particular, which would later become core elements in the shoin style of 17th century architecture. One of these elements was the tokonoma, a small alcove in which scrolls are hung, and flowers or other small articles are placed to enhance the aesthetic feel of the room. The great ink-painter Sesshū Tōyō spent much time at the Ginkaku-ji, and this period also saw the birth of the Kanō school of Japanese painting as well as an early version of chanoyu tea ceremony. Tea ceremony would be further formalized by Sen no Rikyū in the 16th century.

Important dates

In the history of this period, a few specific dates are noteworthy:

Examples

Architecture

- Ginkaku and Garden of Jishō-ji

- Karesansui of Ryōan-ji

- Karesansui of Daisen-in

Calligraphy and painting

- "View of Ama-no-Hashidate" by Sesshū (Kyoto National Museum) (Image)

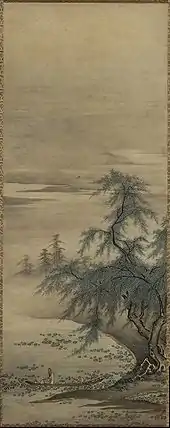

- "Zhou Maoshu Appreciating Lotuses", a hanging scroll by Kanō Masanobu (Kyūshū National Museum)

- "Seikōji engi emaki" by Tosa Mitsunobu (Tokyo National Museum)

"View of Ama-no-Hashidate" by Sesshū

"View of Ama-no-Hashidate" by Sesshū "Zhou Maoshu Appreciating Lotuses", a hanging scroll by Kanō Masanobu

"Zhou Maoshu Appreciating Lotuses", a hanging scroll by Kanō Masanobu "Seikōji engi emaki" by Tosa Mitsunobu

"Seikōji engi emaki" by Tosa Mitsunobu

Notes

- Yasuhiko Murai, tr. Alfred Birnbaum, "A Brief History of Tea in Japan." Chapter One in CHANOYU: The Urasenke Tradition of Tea. Weatherhill, 1988.

- Keene, Donald. (2003). Yoshimasa and the Silver Pavilion, p. 87.

- Titsingh, p. 361.

References

- "Higashiyama Bunka", JAANUS: Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System.

- Keene, Donald. (2003). Yoshimasa and the Silver Pavilion: The Creation of the Soul of Japan. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13056-1; OCLC 52268947

- Titsingh, Isaac, ed. (1834), [Siyun-sai Rin-siyo/Hayashi Gahō, 1652], Nipon o daï itsi ran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Sansom, George Bailey. (1943). "Japan: A Short Cultural History". New York: Appleton Century Crofts, Inc.

- Steiner, Evgeny. (2014). Zen-Life: Ikkyu and Beyond. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-5400-9.