Historic Center of Salvador

The Historic Center (US) or Centre (UK; Portuguese: Centro Histórico) of Salvador de Bahia in Brazil, also known as the Pelourinho (Portuguese for "Pillory") or Pelo, is a historic neighborhood in western Salvador, Bahia.[1] It was the city's center during the Portuguese colonial period and was named for the whipping post in its central plaza where enslaved people from Africa were publicly beaten as punishment for alleged infractions. The Historic Center is extremely rich in historical monuments dating from the 17th through the 19th centuries.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Largo do Pelourinho, Salvador | |

| Location | Salvador, Bahia, Brazil |

| Reference | 309 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th session) |

| Coordinates | 12°58′S 38°30′W |

Location of Historic Center of Salvador in Brazil | |

Salvador was the first colonial capital of Brazil and the city is one of the oldest in the New World (founded in 1549 by Portuguese settlers). It was also one of the first slave markets on the continent, with slaves arriving to work on the sugar plantations.[2] The area is in the older part of the upper city (Cidade Alta) of Salvador. It encompasses several blocks around the triangular Largo, and it is the location for music, dining and nightlife. It has a place on the national historic register and was named a world cultural center by UNESCO in 1985.[1]

In the 1990s, a $100 million restoration effort led by a conservative political coalition tied to then-governor Antonio Carlos Magalhães resulted in the removal of over 4,000 mainly Afro-Bahian residents and the conversion of a once-vital neighborhood into a pastel-hued tourist attraction.[3]

History

Salvador's Historic Center comprises the colonial city's primitive nucleus and its geographical expansion until the end of the 18th century. From Praça Municipal, open within the dense tropical forest by the first general-governor, Tomé de Sousa, in 1549, to largo de Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, battle field where Portuguese and Dutch soldiers from Companhia das Índias Ocidentais fought in 1638, monuments of civil, religious and military architecture make up a scenery that reveals Salvador's inhabitants art and way of living through the centuries. From Portas de Santa Luzia, which kept the southern boundary of the old city safe, with mud walls, to the thick walls of Fort Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, which guarded the north entrance, Salvador's Historic Center is divided in three areas that can be visited all at once: from Praça Municipal to Largo de São Francisco, Pelourinho, and from Largo do Carmo to Largo de Santo Antônio Além do Carmo.

The area between Praça Municipal and Largo de São Francisco chronologically starts from the place chosen by general-governor Tomé de Souza for the construction of the Colonial Government buildings, and in the places occupied by religious brotherhoods that came from Europe in 1549. Praça Municipal was opened because it offered better protection against attacks by natives and corsairs. The Governor's House, the City Hall, the Chapel of Our Lady of Help, and other structures were initially made of mud wall and covered with straw, but later re-built with stone, bricks, and lime. Nowadays, the visitors' preferred historic buildings are the Paço Municipal (completed in the end of the 17th century), the Rio Branco Palace (Palácio Rio Branco, built on the site of the former Governor's House in 1919), and the Lacerda Elevator(Elevador Lacerda), amplified in the thirties. Towards the north are Church and Santa Casa da Misericórdia (Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Misericórdia). The Customs Building at Cayrú Square was constructed in 1861. The Model Market (Mercado Modelo) near the foot of the elevator in the Comércio district claims to be the largest handicraft market in Latin America.[4]

The Church of the Holy See (Igreja da Sé), an integral part of the architectural set of the Historic Center, was demolished in 1933 along with four other blocks of buildings from the colonial and imperial periods. The Archbishop's Palace, connected to the church, remains. Debates over the destruction of historic sites in Salvador and elsewhere in Brazil led to the first attempts at federal-level protection of historic assets and eventually to the establishment of the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage.[5]

The Terreiro de Jesus, just north of Praça Municipal, is home to structures from the 17th to 19th century constructions. Catedral Basilica, former Igreja dos Jesuítas (Jesuit Church), and churches Ordem Terceira de São Domingos and Church of Saint Peter of the Clergymen (São Pedro dos Clérigos) stand out in Terreiro de Jesus, with its beautiful water fountain in the center.[6]

The former Medical School Building, originally occupied by the Jesuit School, is now the Memorial da Medicina (Medicine Memorial), Arqueologia e Etnologia (Archeology and Ethnology), and Afro-Brasileiro (Afro-Brazilian) museums. The House of the Seven Lamps (Casa dos Sete Candeeiros), now a museum, is nearby. Largo do Cruzeiro de São Francisco (Cruzeiro de São Francisco Largo), practically an extension of Terreiro de Jesus, has an old cross in the center, and, on the back, the monumental religious set made up of São Franscisco Church and Convent, and Church of the Third Order of Saint Francis (Ordem Terceira de São Franscisco Church). The Church of the Third Order of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black People (Igreja da Ordem Terceira de Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Pretos), Church of the Blessed Sacrament at Rua do Passo, and Church of the Third Order of Mount Carmel are located further north in the district. Numerous colonial-period historic residences, including the Palace of Saldanha, are located on streets outside of the main plazas.

Many buildings of the Historic Center have been renovated since the initial survey of Salvador by the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage in the 1930s. This work extended to the revitalization of whole blocks of historic houses, convents, and churches from the beginning of the 1990s.[7] There are more than 800 buildings with restored façades and interiors; many were adapted to function as small museums and cultural centers.[8]

Protected status

The Historic Center of Salvador as a whole was listed as a national heritage site by the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage in 1984. It was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1985.[8][1]

References

- "Historic Centre of Salvador de Bahia", World Heritage List, Paris: UNESCO.

- "Historic Centre - Facts", World Heritage Site

- Collins, John. 2015. Revolt of the Saints: Memory and Redemption in the Twilight of Brazilian Racial Democracy. Durham: Duke University Press

- "Model Market of Salvador". Portalmercadomodelo.com.br. Archived from the original on 2010-05-07. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- Riggs, Miriam Elizabeth (2008). 'There's Room for Everyone": Tourism and Tradition in Salvador's Historic District, 1930 to the Present (Ph.D.). University of California, Davis.

- Araujo, Renata Malcher de. "The Coast". Lisbon, Portugal: Heritage of Portuguese Influence/Património de Influência Portuguesa. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- Collins, John F. (2011). ""Culture, Content, and the Enclosure of Human Being: UNESCO's 'Intangible' Heritage in the New Millennium."". Radical History Review. 109: 121–135 – via Project Muse.

- "Centro Histórico de Salvador (BA)" (in Portuguese). Brasília, Brazil: Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (Iphan). 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

External links

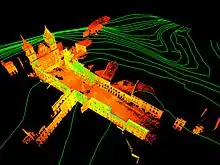

- Pelourinho digital media archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas) from a CyArk/UNESCO research partnership.

- (in English, French, and Dutch) discovering Salvador and Bahia in your language.

- Historic Centre of Salvador de Bahia UNESCO property on google arts and culture