History of Adjara

The article refers to the history of Georgia's Autonomous Republic of Adjara.

| History of Georgia |

|---|

|

|

|

Ancient and medieval Adjara

.jpg.webp)

Archeologists say the territory has been inhabited since the Neolithic Age. Occupied by an ancient Georgian tribe of Moskhs from ancient times, the territory of Adjara was a province of Colchis from the 7th to 3rd centuries BC. Part of the area formed a county (saeristavo) within the Kingdom of Iberia in the late 4th century BC. Colonized by Greek merchants in the 5th and 4th century BC, the coastal Adjara later came under Roman rule. Bathus (Bathys) (the present day Batumi) and Apsaros (Apsaruntos) (modern Gonio) were the key cities and fortresses at that time. Archeological excavations have revealed ruins of a rich ancient town at Pichvnari near the present day town of Kobuleti. In the 2nd century AD, Bathus was an important military base for Roman legions. Apsaros was famous for its theatre.

The early Christian era in Adjara was linked with names of Saint Andrew, Saint Simon the Canaanite and Matata. Saint Matthias is said to be buried in the Gonio fortress near Batumi. In the 2nd century AD, Adjara was incorporated in the kingdom of Lazica. The province's key fortress of Petra (Tsikhisdziri) served as a battlefield during the Lazic War between the Byzantines and Persians in 542–562.

In the 9th century, the region was divided between two Georgian states, the Tao-Klarjeti and the Kingdom of Abkhazia.

In the 11th century, Adjara became a part of the unified Georgian Kingdom and was governed by rulers of Samtskhe-Saatabago. The region was ravaged by Seljuks in the 11th century and by Mongols in the 13th century. After the disintegration of Georgian monarchy and subsequent internal wars, Adjara was passed from hands to hands until it became a part of the Principality of Guria in 1535. The Genoese established one of their Black Sea trading "factories" at the fortified town of Gonio at that time.

Adjara under Ottoman rule

In 1547, the Ottomans raided the province and captured Batumi. Liberated by Prince Rostom Gurieli of Guria in 1564, the region fell under the Turkish rule again in 1582. In 1609, Prince Mamia Gurieli temporarily relieved Batumi. However, Guria lost the province to the Ottomans in 1614. The area was divided into two sandjaks and submitted to the Pasha of Childir (Akhaltsikhe). Part of Adjarians fled to other Georgian regions. Those who remained were converted to Islam. The Ottomans had little direct control of Adjara and local Muslim Georgian nobility, such as the Khimshiashvili, ruled as semi-autonomous beys until the Ottoman government's centralizing reforms tanzimat eliminated them and brought the region more closely within the empire by 1850. There was opposition to the tanzimat efforts from both nobility, who resented the loss of their privileges, and peasantry, who opposed newly allocated taxes and conscription in the regular Ottoman army. In the 1840s, the Porte had to commit significant forces from the neighboring pashaliks to suppress a rebellion staged by Kor-Hussein Bey (Khimshiashvili). Three times did Kor-Hussein Bey rise in revolt, in 1840, 1844, and 1846; each time he was defeated and eventually sent as a prisoner to Constantinople.[1] Among the rebels was Hasan Hasbi, sent, in 1845, by the Caucasian Imam Shamil in Adjara to recruit volunteers for his struggle against the Russian encroachment in Dagestan. After the suppression of the Adjarian uprising, he managed to escape.[2][3]

During the Crimean War of 1853-1856 and Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, thousands of Adjarians were recruited in the Ottoman army. During the war of 1877–1878, Batum was defended by a 25,000-strong Ottoman army under Dervish-Pasha as well as the Ottoman warships cruising off the Black Sea coastline. The Russians dispatched the Kobuleti Detachment of 12,000 troops commanded by Lt.-Gen. Oklobzhio, but he made little progress throughout the conflict. He was able to dislodge the Turks from the Mukha-Estate heights on April 14, 1877, and entrenched there until November 15. The only attempt to advance made by Oklobzhio was thwarted by the Ottomans at the clashes at Tsikhisdziri and the Sameba hills on June 11–12. In November, the fall of Kars and retreat of Dervish Pasha's troops to Batum combined with the advance of General Komarov's Ardahan Detachment to Batum enabled Oklobzhio to reclaim the positions, but the attack on Tsikhisdziri on January 18, 1878, was a failure. Then the ceasefire followed, ending the Russian operations against Batum.

Adjara under Russian rule

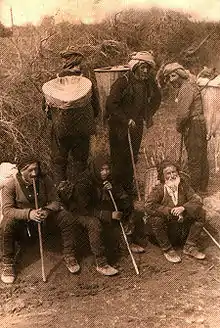

The Ottomans ceded Adjara (called Adjaristan under Turkish rule) to the Russian Empire on March 3, 1878. Under the Russian oppression of Islam, thousands of Muslims fled the region in search of refuge in Turkey in an immigration process called Muhajiroba (see Muhajir (Caucasus)). Financed by the Ottomans, an insurgent organization known as The Avengers attempted to kill Russian officers and officials, along with Adjarians who collaborated with the imperial presence. Nevertheless, many Adjarians were loyal to Russia as they found the best opportunity to be reunited with other Georgians.

The Berlin Congress of 1878 declared the regional capital of Batum a porto franco or free port. The city became an important seaport and industrial city towards the end of the 1880s. At the turn of the 20th century, Batumi was linked to the oil fields of Baku by one of the earliest pipelines (Baku-Batumi pipeline) and a railway, and it became one of the most important ports in the world. On June 22, 1892 the "Markus", a huge tanker ship departed Batumi for Bangkok, Thailand, becoming the first oil tanker to transit the Suez Canal.

The region (called Batum Oblast under the Russian rule) witnessed numerous strikes and bloody crackdowns during the Russian Revolution of 1905-1907.

During World War I, Adjarian muhajirs (emigrants to Turkey) formed a division within the Turkish army. Upon the evacuation of the Russian forces following the ceasefire of December 18, 1917, on 14 April 1918 the Ottoman 37th Caucasian Division entered Batum.

In 1915, in the course of the ongoing war against Ottoman Empire, the Russian administration began a process of deportation of “refractory” Russian-subject Muslims from the Batumi region to interior Russian provinces, drawing protests from Georgian intellectuals. Soon thereafter, Georgian deputies in the Russian Duma declared that the Muslims being deported were not Turks but Adjarians, who were “Georgian despite their Muslim religion, and therefore loyal Russians.” As a result of their protests, Grand Duke Georgi Mikhailovich presided over an investigation which ended its voluminous report with the conclusion that there Adjarians were not hostile to the Russian regime. It blamed Cossacks and Armenians for the allegations of Adjarian disloyalty and accused them of instigating violent confrontations with local Muslims. In the end, Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolaevich was persuaded to meet with Adjarian leaders, and he even awarded them for their loyalty. It was not until after the Russian Revolution of 1917, on January 26, 1918, that the investigation of alleged Adjarian treason was closed.[4]

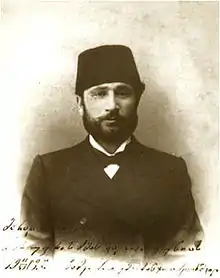

British Occupation

On January 12, 1919 the British expeditionary forces landed at Batumi to replace the Turkish troops. The Council for Batum Region — chaired by the Russian cadet P. Maslov — was created to govern Adjara as a provisional authority from 21 December 1918 to 28 April 1919. The Committee of the Liberation of Muslim Georgia, led by Memed Abashidze and Haidar Abashidze, had repeatedly spoken of the establishment of autonomy on religious principles within the borders of Georgia. To work towards this, on September 13, 1919 a prototype parliament, the Mejlis, was convened in Batum. Though Abashidze's faction strongly advocated the union with Georgia, the drive towards autonomy was strong, even among the pro-Georgian Adjarians. Another, less numerous group known as Seday Mileth (in Turkish: "voice of people") propagated pro- and pan-Turkish ideas.

On August 15, 1919, the withdrawal of British Troops began from the Caucasus. The divisional headquarters at Batum left for Constantinople, handing over to the military governor of Batum—Br.-Gen. W. J. N. Cooke-Collis. On March 4, 1920, Cooke-Collis as appointed to command the Inter-Allied Force at Batum. This force was withdrawn from Batum by July 14, 1920.

Adjara in Democratic Republic of Georgia

The British administration ceded the region to Georgia on 20 July 1920. Bolsheviks and Russian agents organized a series of sabotages and terrorist acts. The administration of democratic Georgia accepted the idea of Adjara's autonomy, although it was only realized under Soviet rule.

During the Soviet invasion of Georgia, Turkish forces occupied Batumi on March 11, 1921 and held the city until they were expelled by the Georgian troops under General Giorgi Mazniashvili on March 18, 1921. The Soviet rule in Batumi was declared the next day. Turkey recognized the region as a part of Georgian SSR by the Soviet-Turkish Treaty of Kars of 16 March 1921.

Adjara under Soviet rule

The Soviet government declared the Adjar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on 16 July 1921. Turkey ceded the region to Bolsheviks on the condition that it would be granted autonomy, for the sake of the Muslims among Adjara's mixed population. It is thought also that Moscow wanted to avoid giving Georgia complete control of the important Black Sea port of Batumi and to bolster Communist leanings among the ethnic Georgian Muslims living in Turkey. Under Joseph Stalin, Islam, like Christianity, was repressed.

In April 1929, the Muslim villagers of mountainous Adjara rose in arms against compulsory collectivization and religious persecution. The Soviet troops were invoked and the revolt was quickly put down. Thousands of Adjarians were deported from the republic.[5]

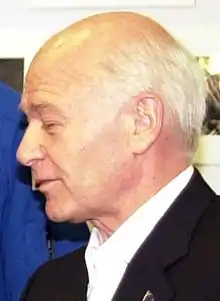

Adjara under Aslan Abashidze

.svg.png.webp)

Following Georgia's first democratic parliamentary and presidential elections, President Zviad Gamsakhurdia appointed Aslan Abashidze as the head of the Adjara's Supreme Council on March 15, 1991 hoping that the latter would assist in canceling the autonomous status of the region. However, when Gamsakhurdia proposed to abolish Adjarian autonomy, Abashidze called Adjarians, especially the Muslims of the region, to rise in protest. Tensions with central Georgian authorities ensued. On 22 April 1991, pro-Abashidze protesters stormed administrative buildings in the central Batumi demanding the immediate resignation of several officials. The protests were effectively used by Abashidze to establish his own powerbase in the region. Gamsakhurdia facing serious internal problems already in Tbilisi preferred not to interfere in the Adjarian events. In turmoil, Nodar Imnadze, Abashidze's deputy chairman of the Supreme Soviet and the highest placed supporter of Gamsakhurdia in Adjara, was killed in highly controversial circumstances. In Batumi's version, Imnadze was shot by guards while attempting to burst in Abashidze's office with a gun in his hands. The Tbilisi-controlled media simply printed unspecified obituaries. However, many claims have been made that Imnadze was killed by Abashidze himself during the argument at office.

Under Abashidze's tight control of the autonomy, Adjara enjoyed relative political stability and economic prosperity during the Georgian Civil War. However, the majority of the Adjarians remained poor despite much foreign investment and numerous financial projects. On 24 October 1997, Adjara became a full member of the Assembly of European Regions (AER).

The relations between the central and regional authorities were strained. Adjarian leadership often refused to pay taxes to the central budget. Abashidze took control over the customs, Batumi seaport and other strategic objects. He created his own semi-official armed units and had full control over the Batumi-based 25th Brigade of Georgia's Defense Ministry.

The central government claimed Batumi-based Russian military unit was a powerbase for the Adjarian strongman and criticized Abashidze for his pro-Russian orientation.

Georgia's ex-president Eduard Shevardnadze visited the region several times during his rule in 1992–2003 to attempt reconciliation with Abashidze. They reached a kind of compromise in which Adjara obtained larger autonomous status, Abashidze agreed not to run for the presidency of Georgia, and Shevardnadze allowed Abashidze to maintain power in Adjara. The latter's party, the Union of Democratic Revival of Georgia, cooperated with Shevardnadze's ruling Union of Citizens of Georgia party in the 1995 parliamentary elections, but broke with Shevardnadze after the elections.

Abashidze's Revival Party had thirty members in the Georgian parliament, and was seen as a moderate opposition to the central government in Tbilisi. After the rigged elections of 2003 and the ensuing "Rose Revolution" in Georgia, Abashidze described the November 2003 ouster of Shevardnadze as "a violent coup d'état".

Adjara crisis

On November 23, 2003, immediately after Shevardnadze's fall, Aslan Abashidze declared a state of emergency in the region. Nevertheless, Adjara took part in the Georgian presidential elections of January 4, 2004, won by Mikheil Saakashvili. Saakashvili ordered the Adjarian leader to comply with the Georgian constitution and start disarming. In May 2004, Abashidze claimed that Georgian forces were preparing to invade. His forces blew up bridges connecting the region with the rest of Georgia. The state of emergency was followed by the dispersal of local oppositional demonstrations as of May 4. This proved a catalyst for even larger demonstrations later on the same day. Tens of thousands from all Adjara headed for Batumi to demand Abashidze's resignation. On May 6, Abashidze's position became untenable when local protesters took control over the central Batumi and Georgian Special Forces entered the region and started to disarm pro-Abashidze groups. After overnight talks with Russian Foreign Affairs Minister Igor Ivanov, Mr. Abashidze resigned and departed the country for Moscow.

Post-Abashidze era

On May 7, 2004 direct presidential rule was imposed in Adjara and 20-member Interim Council was set up to run the Autonomous Republic before the fresh local elections could be held in the region. Levan Varshalomidze was appointed as the Chairman of the Interim Council.

Regional parliamentary elections were held on June 20. Victorious Adjara, party backed by President Saakashvili won 28 seats out of 30 in the local legislative body. The 2 other seats were occupied by Saakashvili's former allies, the Republican Party. There were allegations of vote-rigging from the Republicans, after they won less than 15 per cent of the vote. On July 20, Adjarian Supreme Council approved Levan Varshalomidze as the Chairman of the Autonomous Republic's Government.

The regional policy of central and local governments focuses on attracting foreign investments in the region. A largescale campaign of privatization has been launched for this purpose.

Russian military presence was another challenge in the region. Russia promised to withdraw its base at the 1999 Istanbul OSCE summit, and the protracted process of the ensuing negotiations remained a source of great tension with Georgia until the base was finally withdrawn by 2008.

See also

References

- Yilmaz, Özgür (August 2014). "Tanzimat Döneminde İsyancı Bir Ayan Profili: Acaralı Kör Hüseyin Bey Hadisesi" [A Rebel Ayan Profile in the Tanzimat Period: The Incident of Kör Hüseyin Bey of Adjara]. Belleten (in Turkish). 78 (282): 611–657.

- Gammer, Moshe (2003). Muslim Resistance to the Tsar: Shamil and the Conquest of Chechnia and Daghestan. Taylor & Francis. pp. 250–251. ISBN 0714650994.

- Badem, Candan (2010). The Ottoman Crimean War (1853–1856). Brill. pp. 149–150. ISBN 90-04-18205-5.

- Eric Lohr (2003), Nationalizing the Russian Empire: the Campaign against Enemy Aliens during World War I, pp. 151-2, 220-1. Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01041-8.

- Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis (1977), The Cambridge history of Islam, p. 639. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29136-4