History of Denver

The history of Denver details the history of the City, and County of Denver, Colorado, the United States from its founding in 1858 to modern-day. Located on the banks of the South Platte River close to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, Denver was founded in November 1858 as a gold mining town. The gold quickly dried up and the city moved to become a supply hub for new mines in the mountains. Denver grew rapidly, becoming the new county seat of Arapahoe County and eventually the state capital. Investors from Denver built a rail line from Cheyenne to western Kansas which traveled through Denver, bringing new people and supplies. New roads and improvements to rail and air travel in the early twentieth century made Denver a hub for transportation. Until World War II Denver's economy was dependent mainly on the processing and shipping of minerals and ranch products. With war looming, Denver was in a prime location for more federal activity, being situated far from either coast. After the war, oil and gas companies fueled a skyscraper boom in the downtown area. With the combined spending of the energy companies and the federal government, Denver expanded quickly. Denver went from having a small urban core surrounded by rural farms to a booming downtown dotted with skyscrapers and surrounded by growing suburbs.

19th century

Pike's Peak Gold Rush and first settlements

The Denver area, part of the Territory of Kansas, was sparsely settled until the late 1850s. Occasional parties of prospectors came looking for gold, then moved on. In July 1858, Green Russell and Sam Bates found a small placer deposit near the mouth of Little Dry Creek (in the present-day suburb of Englewood) that yielded about 20 troy ounces (620 g) of gold, the first significant gold discovery in the Rocky Mountain region. News spread rapidly and by autumn, hundreds of men were working along the South Platte River. By spring 1859, teams of thousands of gold seekers arrived and the Pike's Peak Gold Rush was under way. In the following two years, about 100,000 gold seekers flocked to the region.[1]

In the summer of 1858 a group from Lawrence, Kansas, arrived and established Montana City on the banks of the South Platte River (modern-day Grant-Frontier Park). This was the first settlement in what would become the Denver Metropolitan Area. The site faded quickly due to poor findings by miners and most of the settlers and some structures moved north to the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek and formed a new settlement named St. Charles.[2] The location was accessible to existing trails and had previously been the site of seasonal encampments of the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

In October 1858, five weeks after the founding of St. Charles, the town of Auraria was founded by William Greeneberry Russell and party of fellow settlers from Georgia on the south side of Cherry Creek. The town, named for the gold mining settlement of Auraria, Georgia, was formed in response to the high cost of land in St. Charles and gave away lots to anyone willing to build and live there. A post office was opened in Auraria in January 1859 serving the 50 cabins that had already been constructed.[2]

A short time later a third town, called Highland was founded on the west side of the South Platte River. Surrounded by steep bluffs and separated from the other two settlements by the river, it was slow to develop.[3][4]

Larimer Party

In November 1858, General William Larimer and Captain Jonathan Cox, Esquire, two of the land speculators from eastern Kansas Territory that had met with the Territorial Governor James W. Denver (who honorarily gave them appointments such as commissioner, judge and sheriff[5]) unpacked their wagons and divided up the supplies. Larimer looked over the Auraria landscape. and was not satisfied with the first area chosen. He moved to a new area where he set up a campfire and four cottonwood poles crossed together, creating the first "Larimer Square"[6] to stake a square-mile claim on the site of the St. Charles claim, across the creek from the existing mining settlement of Auraria. The majority of the settlers in St. Charles had returned to Kansas for the winter and left only a small number of people behind to guard their claim, including one of their leaders named Charles Nichols. Larimer and his followers gave the representatives whiskey, promises, and the threat of a noose,[7] whereby the St. Charles claim was surrendered.[2][8]

The name of the site was changed to "Denver City" after Kansas Territorial Governor James W. Denver, in an attempt to ensure that the city would become the county seat of then Arapaho County, Kansas. Ironically, when Larimer named the city after Denver to curry favor with him, Denver had already resigned as governor and no longer had say in naming the capitol.

In Denver, in the winter of 1858–1859, Katrina Wolf Murat, assisted by Wapolah, a Sioux, sewed together the first flag of the United States in Colorado.[9]

Denver at first was a mining settlement, where gold prospectors panned gold from the sands of nearby Cherry Creek and the South Platte River. Larimer, along with associates in the Denver City Land Company, laid out the roads parallel to the creek and sold parcels in the town to merchants and miners, with the intention of creating a major city that would cater to new immigrants.[10] In the early years, land parcels were often traded for grubstakes or gambled away by miners in Auraria. However, the prospectors discovered that the gold deposits in these streams were discouragingly poor and quickly exhausted. When rich gold deposits were discovered in the mountains west of Denver in early 1859 it appeared that Denver City might become a ghost town as prospectors left for more lucrative claims. However, once the gold rush began there was a great need for materials that couldn't be produced locally, which assured Denver's future as a supply hub for the new mines.[2][11]

Before the gold rush, trading was sparse in the Denver area. Early expeditions into the area, such as the Pike and Long expeditions, had returned east referring to the plains as the "Great American Desert", which deterred immigration. Despite this, frontier posts and forts existed and traded with the natives and frontiersmen. However, the closest major trading routes, the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails, were not within a hundred miles of the Denver area. Until a permanent trading route was established the locals had to make do with what little extra the new immigrants brought with them.

Auraria and Denver began to compete for businesses that could cater to the new immigrants and for domination of the area. Auraria began to take an early lead with the first saloon, smithery, and carpentry shop. However, in May 1859, Denver City donated 53 lots to the Leavenworth and Pike's Peak Express in order to secure the region's first overland wagon route. Offering daily service for "passengers, mail, freight, and gold," the Express reached Denver on a trail that trimmed westward travel time to as few as six days. With supplies being delivered to the Denver side of Cherry Creek, businesses began to move there as well. By June Auraria had 250 buildings compared to Denver's 150 buildings, and both cities were growing quickly. With this growth came a need for a wider government.[12]

The new territory of Colorado

Denver, Auraria and the land west to the Continental Divide were part of Arapahoe County which encompassed the entire western portion of the Kansas Territory. At the creation of Arapahoe County in 1855 it was occupied primarily by Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians with only a few white settlers, and thus the county was never organized. With no county government and the leaders of the Kansas Territory preoccupied with the violent events of Bleeding Kansas, little time or attention was given to those in Arapahoe County even by the United States Congress who were preoccupied with threats of secession by the slave states. In addition the gold fields were beginning to move beyond the borders of the Kansas Territory and because of their importance and ties to mining activity closer to Denver, calls began for a new territory or state.[4]

On October 24, 1859, an election was held to form a provisional government for the goldfields and the formation of the Provisional Government of the Territory of Jefferson was approved. The elected Governor of the Territory of Jefferson, Robert Williamson Steele, opened the first session of the Jefferson Territorial Legislature in Denver City on November 7, 1859. The Congress, embroiled in the debate over slavery, failed to consider the new territory. The election of Abraham Lincoln for the President of the United States eliminated any chance for federal endorsement of the Territory of Jefferson and any role in government for Governor Steele, a staunch pro-Union Democrat and vocal opponent of Lincoln and the Republican Party.

Seeking to augment the political power of the free states, the Republican led congress hurriedly admitted the portion of the Territory of Kansas east of the 25th meridian west from Washington to the Union as the free State of Kansas on January 29, 1861. Kansas statehood left the western portion of the now defunct Kansas Territory, which the Jefferson Territory also claimed, officially unorganized.

On February 28, 1861, outgoing U.S. President James Buchanan signed an Act of Congress organizing the free Territory of Colorado.[13] President Abraham Lincoln appointed William Gilpin of Missouri the first Governor of the Territory of Colorado and he arrived in Denver City on May 29, 1861. On June 6, 1861, Governor Steele issued a proclamation declaring the Territory of Jefferson disbanded and urging all employees and residents to abide by the laws governing the United States.

The Colorado General Assembly first met on September 9, 1861 and created 17 counties for the territory on November 1, 1861,[14] including a new Arapahoe County with Denver City as its seat. The legislature approved the reincorporation of the cities of Denver, Auraria, and Highland as Denver City on November 7, 1861 in order to better administer the quickly growing cities.[4][15]

Denver City served as the Arapahoe County Seat from 1861 until it became its own county in 1902. In 1867, Denver City became the Territorial Capital. With its new-found importance, Denver City shortened its name to just Denver. On August 1, 1876, Denver became the temporary state capital when Colorado was admitted to the Union, and a statewide vote in 1881 made Denver the permanent state capital.[14][16]

The turbulent 1860s

Before 1861, Denver was technically part of Arapahoe County, Kansas. However, because the county was never organized, there was a lack of government services that resulted in vendettas and vigilantism, but also entrepreneurialism. William Hepworth Dixon, an English traveler, once noted of Denver, "a man's life is of no more worth than a dog's", but that in its people he saw "perseverance, generosity, [and] enterprise." After Colorado became a territory courts were set up, judges were appointed, and laws were created but mob justice was still common.[17]

The same year that Colorado became a territory, the American Civil War broke out and Colorado was not spared. Most Denverites were from the North and their support for the Union drove many Southerners from town, including Denver's first mayor John C. Moore. William Gilpin, Colorado's first territorial governor, organized Colorado's volunteer militia, and sent them south in February 1862 to fight Confederate Texans at the Battle of Glorieta Pass. With resources tied up in the war there was little left over for mines, farms, and infrastructure, and Denver stagnated.[17]

Though Denver surpassed most other cities in Colorado at the time and was transforming itself, it was still considered a frontier town. Churches, lacking permanent facilities, often held their services in public halls or saloons, and children attended pay schools led by teachers of questionable ability. Gold mining declined as miners exhausted the shallow parts of the veins that contained free gold, and found that their amalgamation mills could not recover gold from the deeper sulfide ores.[18] Many people left Colorado, and often those who stayed lacked continuous work during the economic slump, often spending their time drinking and getting into fights.

Denver's early wooden buildings were extremely flammable, and on July 15, 1862 citizens organized a volunteer Fire Department. Unfortunately, almost a year later, carts and buckets were still on order, and firemen were untrained and untried. On April 19, 1863, a fire broke out in the center of downtown Denver. High winds fed the sparks and, in a few hours, a great majority of the wooden buildings in the heart of Denver were destroyed. Losses totaled over $250,000, and although the buildings themselves were of minimal value, the loss of inventory devastated many new businesses. As a result of the fire, new laws were passed to prohibit using wood and other flammable materials to construct downtown buildings. Denver's new buildings were built with brick, often larger than the original. As the rebuilding progressed, Denver began to look like a town rather than a temporary campground.[19]

On May 19, 1864, just over a year after the fire, the spring melt combined with heavy rains caused severe flooding on Cherry Creek. The flooding severely affected the low-lying Auraria, destroying the Rocky Mountain News building, the Methodist Church, City Hall, and numerous offices, warehouses, and outbuildings. Eight Denver residents were killed, and enormous number of livestock were drowned. Financial losses totaled approximately $350,000 and left many homeless. The water was badly contaminated and threatened a major epidemic. Despite these overwhelming losses, rebuilding began almost immediately. Ignoring the risk, many rebuilt well within the flood plain, and flood waters subsequently engulfed Denver in 1875, 1878, 1912, and 1933. It was not until the 1950s, when the Army Corps of Engineers completed Cherry Creek Dam, that the flooding was stopped.[19]

The summer of 1865 saw attacks on supply trains and market manipulations drive up prices. In 1865, grasshoppers swarmed through the area, stripping away all the vegetation. Real estate values fell so low that entire blocks changed hands during poker games. The town's population shrank from 4,749 in 1860, to only about 3,500 in 1866. Many of the original gold miners and town founders were among those who left.[17]

By the mid-1860s the Civil War was over and Denver had survived many tragedies. The city began to grow again and ended the decade with a population of 4,759. With the freeing up of capital that the end of war brought, new investment was once again possible. Denverites began to look toward the next step for growing their city, ensuring that the route of the transcontinental railroad would pass through Denver.

The Transcontinental Railroad

With investment once again flowing into the Denver area transportation became a greater concern. Transporting goods to and from Denver was a large expense, an expense that railroads could alleviate. In 1862 the United States Congress passed the Pacific Railway Act and Coloradans were excited at the prospect of the railroad crossing the Rockies Mountains through Colorado despite the dismal surveys by John C. Frémont and John Williams Gunnison. When the Union Pacific Railroad chose to go north through Cheyenne, Wyoming many at the time expected that Cheyenne would blossom into the major population center of the region. Thomas Durant, vice president of the Union Pacific, pronounced Denver "too dead to bury." Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans declared that "Colorado without railroads is comparatively worthless."[20]

As a result, Evans, together with other local business leaders, partnered with East Coast investors to form a railroad company that would link Denver and the Colorado Territory with the national rail network. The company was incorporated on November 19, 1867 as the "Denver Pacific Railway and Telegraph Company." The sense of urgency for the Denver boosters was enhanced by the formation of a rival, the Colorado, Clear Creek and Pacific Railway (later the Colorado Central Railroad), by W.A.H. Loveland and citizens of nearby Golden, with the intention of linking that city directly with Cheyenne and making Golden the natural hub of the territory.

Within several days, the company sold $300,000 in stock, but were unable to raise further funds to begin construction. The efforts seemed to be on the brink of failure when Evans was able to persuade Congress to grant the company 900,000 acres (3,600 km2) of land on the condition that the company build a line connecting the Union Pacific line in Wyoming with the existing Kansas Pacific line, which then extended only as far west as central Kansas.

Racing to beat the Golden investors, the company broke ground on its Cheyenne line on May 18, 1868 and took approximately two years to complete. The first train from Cheyenne arrived in Denver on June 24, 1870. Two months later, in August 1870, the Kansas Pacific completed its line to Denver and the first train arrived from Kansas. With the completion of the Kansas Pacific line to Denver, the Denver Pacific became integral to the first transcontinental rail link between the east and west coasts of America. While the Union Pacific line had been declared finished in 1869 with the Golden spike event in Utah, linking it with the Central Pacific Railroad, passengers were required to disembark the train and cross the Missouri River at Omaha by boat. With the completion of the Denver Pacific line, it was finally possible to embark a train on the east coast and disembark on the west coast.

The Denver Pacific's rival, the Colorado Central line from Golden, was not completed until 1877. By this time, Denver had established its supremacy over its rival as the population center and capital city of the newly admitted State of Colorado. The railroad brought residents, tourists, and much-needed supplies. In the 1870s, it is estimated that the railroad brought 100 new residents to Denver each day. Population statistics bear this out, for Denver's population soared from 4,759 in 1870 to over 35,000 by 1880. In addition to bringing new residents, it put Denver on the map as a tourist destination and brought 1,067 visitors in its first month of operation. That first month also brought 13,000,000 pounds (5,900,000 kg) of freight. Denver now had the people and supplies it needed to flourish and solidify its dominance in the region.[19]

Denver during the silver boom

Silver was discovered near Montezuma, Georgetown, Central City and Idaho Springs in the mid-1860s, but mining was delayed for the most part until smelters were built in the late 1860s. Despite the early silver discoveries, Colorado's largest silver district, Leadville, was not discovered until 1874. With silver mining in Colorado booming much wealth came to the residents of Denver.

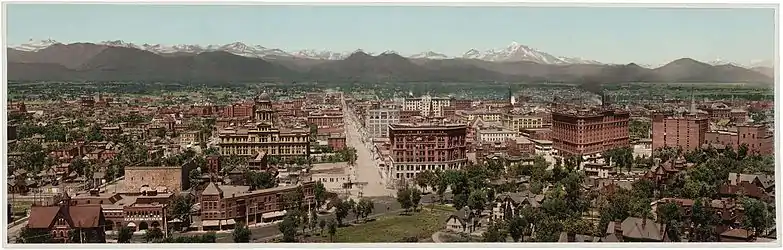

The city's economy was gaining a more stable base rooted in railroads, wholesale trade, manufacturing, food processing, and servicing the growing agricultural and ranching hinterland. Between 1870 and 1890, manufacturing output soared from $600,000 to $40 million, and population grew by a factor of 20 times to 107,000.[21] By 1890, Denver had grown to be the 26th largest city in America, and the fifth-largest city west of the Mississippi River.[22] The rapid growth of these years attracted millionaires and their mansions, as well as poverty and crime.

From Denver's start as a gold mining town through its transformation into a supplier of goods and services, it had always been a place where miners, workers, and travelers could spend their hard earned money. Saloons and gambling dens sprung up quickly after the founding. In 1859, the Apollo Hall theater opened followed over the years by such notables as the Denver Theatre, home to the city's first opera performance in 1864, and the Broadway Theatre which brought in internationally renowned performers, but none was quite as luxurious as the Tabor Grand Opera House built in 1881.

Built by Horace Tabor with the money he had made mining silver, the Tabor Grand Opera House in Denver was said to be the most opulent building and the best-equipped theater between Chicago and San Francisco at its opening. It occupied the entire block and was claimed to have single-handedly changed Denver's image of itself from a frontier boomtown to a world class city.[23] The following years saw many other grand buildings erected, including Union Station in 1881, the 10-story Brown Palace Hotel in 1892, and the Colorado State Capitol Building in 1894 as well as splendid homes for millionaires like the Croke, Patterson, Campbell Mansion at 11th and Pennsylvania and the now-demolished Moffat Mansion at 8th and Grant.[24] The city was beginning to take on a "big city" image.

The 1880s and 1890s saw corruption as well as progress. Underworld bosses such as Soapy Smith and Lou Blonger worked side by side with city officials and police to profit from gambling and other criminal enterprises. There were a range of bawdy houses, from the sumptuous quarters of renowned madams such as Mattie Silks and Jenny Rogers to the squalid "cribs" located a few blocks farther north along Market Street. Edward Chase ran card games and regularly entertained many of Denver's most influential leaders. Gambling flourished and bunco artists exploited every chance to separate miners from their hard-earned gold. Business was good; visitors spent lavishly, then left town. As long as madams conducted their business discreetly, and "crib girls" did not advertise their availability too crudely, authorities took their bribes and looked the other way. Occasional cleanups and crack downs satisfied the demands for reform.[25] Before Colorado became a territory in 1861 there were no functioning court system and justice was carried out by the public. Once a territory, a justice system was set up for the county but it wasn't until 1874 that Denver created a position for chief of police. These early lawmen had to deal with the Vigilance Committee, often called the Law and Order League, which took matters of law into its own hands. Elizabeth Wallace writes of these vigilantes, "A judge presided and the offender was tried by a group of his peers. Once given, the decision was final. Between 1859 and 1860 fourteen men were accused of murder and were brought before a jury of twelve men and at least one judge presiding. Six of the fourteen men were sentenced to death."[26]

Crime and corruption brought out others who wanted to combat it. Women's suffrage came early, in 1893, led by married middle-class women who organized first for prohibition and then for suffrage, with the goal of upholding republican citizenship for women and purifying society.[27] The Social Gospel was the religious wing of the progressive movement which had the aim of combating injustice, suffering and poverty in society. Protestants, Reform Jews and Catholics helped build Denver's social welfare system in the early 20th century by providing for the sick and hungry.[28] Thomas Uzzel, leader the Methodist People's Tabernacle, established a free dispensary, an employment bureau, a summer camp, night schools, and English language classes. The Baptist minister Jim Goodheart, city chaplain and director of public welfare in 1918, set up an employment bureau and provided food and lodging for the homeless at the mission he ran. The United Way of America has roots in Denver, where in 1887 church leaders began the Charity Organization Society, which coordinated services and fund raising for 22 agencies.[29] Myron Reed, a leading Christian socialist, pastor of the affluent First Congregational Church and a leader in the city's Charity Organization Society, questioned that organization's efforts to distinguish the "worthy" from the "unworthy" poor, spoke out for the rights of labor unions as well as for African American and Native American rights while denouncing Chinese and eastern European immigrants as dependent tools of corporations who were lowering "American" standards of living.[30]

Around the same time Colorado gained the nickname "The World's Sanatorium" for its dry climate which was considered favorable for curing respiratory diseases, tuberculosis in particular. Many people came from the East Coast looking for a cure, bringing with them training and skills which expand the industrial base of Denver. A number of Jews eventually established two well-renowned hospitals to take care of their health needs and serve their community: National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives (now National Jewish Health) and the Jewish Consumptives' Relief Society.[31]

Intent on transforming Denver into one of the world's great cities, leaders had wooed industry and enticed laborers to work in new factories. Soon, in addition to the elite and a large middle class, Denver had a growing population of German, Italian, and Chinese laborers, soon followed by African-Americans and Spanish-surname workers. Unprepared for this influx, the Denver Depression of 1893 unsettled political, social, and economic balances, laying the foundation for ethnic bigotry, such as the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the Red Scare, as well as corruption and crime.[32]

The Panic of 1893 and home rule

In 1893, financial panic swept the nation, and the silver boom collapsed. Denver was already suffering economically due to several successive years of droughts and harsh winters that had hurt the agricultural industry.[33] Agricultural distress, coupled with the withdrawal of foreign investors and the over-expansion of the silver mining industries, led stock prices to decline, banks to close, businesses to fail, and numerous farms to cease operation. With no federal insurance to support the money in the banks, many people lost their life savings.[34] As Denver banks closed, real estate values dropped, smelters stopped working, and Denver Tramway had trouble getting people to ride and pay their fares.[35] The Union Pacific Railroad, which had absorbed both the Denver Pacific and Kansas Pacific in the 1880s, declared bankruptcy.

National unemployment was estimated to be between 12% - 18% in 1894.[36] Wages fell and a wave of severe strikes took place: notable in Colorado was the Cripple Creek miners' strike which lasted five months. As the silver mines began to close due to the continued drop in silver prices, unemployed miners and other workers from the Colorado mountains flooded into Denver in hopes of finding work. Because of the city's inability to take care of the jobless, some train companies began offering reduced or free fares for people wanting to travel from Denver. This effort contributed to the exodus from the city, and Denver's population dropped from 106,000 in 1890 to 90,000 in 1895.[37]

A new municipal charter was given to Denver in 1893 by the state legislature that decentralized much of the mayor's powers into six different administrative departments, two of which were elected, two appointed by the mayor, and the remaining two appointed by the governor. King writes "The plan gave the maximum of opportunity for [political] party groups and corporate control." The municipal board members appointed by the governor had complete financial control over the police, fire, and excise departments. Over half the expenditures of the city went through this board which gave the governor and his party much direct control over Denver.[4]

Governor Davis Hanson Waite, elected in 1893 on a Populist Party reform platform, tried to overturn the corruption in Denver in 1894 by removing police and fire commissioners that he believed were shielding the gamblers and prostitutes that he believed were resulting from and also worsening the depression. The officials refused to leave their positions and were quickly joined by others who felt their jobs were threatened. They barricaded themselves in City Hall, and the state militia were sent to remove them. Federal troops were called in from nearby Fort Logan to intervene and quell the civil strife. Eventually Governor Waite agreed to withdraw the militia and allow the Colorado Supreme Court to decide the case. The court ruled that the governor had authority to replace the commissioners, but he was reprimanded for bringing in the militia, in what became known as the "City Hall War".[38]

That the governor, elected by the entire state, had so much power over the workings of Denver was not lost on the citizens of the city. As the economy faltered, the inefficiency and divisions of the new six department system became more evident. The electorate became disillusioned with the major political parties and in 1895 the first non-partisan mayor in Denver's history was elected, T. S. McMurray. Reelected in 1897, he was ultimately defeated in 1899 in by the "big mitt", a ballot-stuffing campaign. Dissatisfaction with the major political parties that controlled the state legislature led to a "home rule" movement. In 1902 an amendment to the state constitution was passed that allowed cities to adopt home rule and Denver became a consolidated city–county.[4]

The U.S. economy began to recover in 1897 and while jobs slowly began to trickle back into Denver, real estate prices remained depressed through 1900. Throughout the depression, the one constant industry was agriculture. A developed irrigation infrastructure and increasing crop diversification led to a stable food industry throughout the state. Without the jobs brought by the production and processing of food, the depression in Denver would have been much worse. Denver gained back the population it had lost during the depression, mainly through the annexation of neighboring towns, and ended the century with a population of more than 133,000.[4]

20th century

The Progressive Era

The Progressive Era brought an Efficiency Movement typified in 1902 when the city and Denver County were made coextensive. In 1904 Robert W. Speer was elected mayor and initiated several projects that added new landmarks, updated existing facilities, or improved the city's landscape including the City Auditorium, the Civic Center and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.[39] City leaders went to Washington D.C. and after assuring the politicians there that Denver was no longer a frontier town, secured the first major party convention in a western state, the 1908 Democratic National Convention.[40]

Denver pioneered the juvenile court movement under Judge Ben Lindsey, who gained national fame for his efforts. Through his efforts, an act was passed creating a juvenile court in Denver which represented an important advance in relation of the law to children.[41] In 1914, Emily Griffith, a Denver school teacher, opened the Opportunity School which featured language and vocational instruction as both day classes and night classes so that non traditional learners would have the opportunity for self-improvement. Also during this period Denver's park system was expanded and land in the mountains was acquired for a future mountain park system.[20] Cattle pens began to spring up around the existing railroad depots as farmers began shipping their livestock to the existing meat packing industry in Kansas City and Chicago. Local ranchers wanted to concentrate on raising cattle rather than the logistics of shipping them east and in 1906 the first National Western Stock Show was held which quickly became the preeminent livestock show in the region. These events helped raise the national profile of Denver and live up to its nickname, the "Queen City of the Plains."

Labor unions were active in Denver, especially the construction and printing crafts affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and the railroad brotherhoods. After being welcomed at the 1908 Democratic National Convention, the AFL unions, who formed the Denver Trades and Labor Assembly, generally supported Democratic candidates.[42] In early 1913, members of the Industrial Workers of the World, known as the Wobblies, conducted a free speech fight in Denver. City authorities had refused to allow IWW organizers to speak to people on street corners. Union members challenged the policy, with the aim of filling the jails to put pressure on city leaders. The Wobbly tactic, which they had employed successfully for half a decade throughout the North and West, clogged the courts so they couldn't handle anything but free speech cases. Taxpayers complained that they were being forced to feed "whole armies of jailed Wobblies."[43] In her autobiography, Emma Goldman wrote of twenty-seven IWW members, arrested during the Denver free speech fight, who were "tortured in the sweat-box for refusing to work on the rock-pile. On their release they marched through the streets with banners and songs..."[44] The union eventually won the right to speak to workers, and within a year had formed two Denver "branches."[45]

On the brink of World War I, Denver mirrored the rest of the nation in wanting to stay neutral. However, once America entered the war in 1917, Denver contributed what it could to the war effort. Clothing and supplies were donated, children enrolled in agricultural and garden clubs to free up young men for the war, and mining and agricultural interests were expanded to support the troops and the nation. As prices for goods rose with the demand from the war effort farmers began planting crops in greater numbers and mining companies opened new mines for molybdenum, vanadium, and tungsten.[20]

With the United States fighting the Germans in Europe, anti-German sentiment in Denver was at an all-time high. Before the war Germans had been a very prosperous immigrant group, who often congregated in their own ethnic clubs. They had enough political clout to have a law passed in 1877 that required German and gymnastics be taught in public schools, and until 1889 all of Colorado's laws were printed in English, Spanish, and German. The Germans built churches and owned interests in mining and agriculture, but many in the temperance movement primarily associated them with the production and consumption of alcohol. Believing all evil began with the drink, prohibitionists cracked down on "un-American" activity and in 1916 alcohol was banned in the state. Many saloon owners and brewers lost their jobs and with the outbreak of World War I, many others were fired and ostracized. German stopped being taught in schools and many Germans abandoned their heritage to avoid conflicts.[46]

Many individuals within the prohibition movement associated the crime and morally corrupt behavior of the cities of America with their large immigrant populations. In a backlash to the new emerging realities of the American demographic, many prohibitionists subscribed to the doctrine of "nativism" in which they endorsed the notion that America was made great as a result of its white Anglo-Saxon ancestry. This fostered xenophobic sentiments towards urban immigrant communities who typically argued in favor of abolishing prohibition.[47] These sentiments led many in Denver to join the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) both because it opposed foreign immigration and because it defended prohibition.[48] The KKK became a powerful group in Colorado during this time, helping to elect KKK members Benjamin F. Stapleton mayor of Denver in 1923 and Clarence Morley Governor of Colorado in 1925 and receiving government postings for many of its other members.[48] Roman Catholic immigrants, particularly of Irish, Italian, and Polish descent, and Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe were often the target of KKK discrimination. As these communities became Americanized, the KKK lost influence especially during Morley's single scandal ridden term in office. As Prohibition lingered on many citizens saw the negative effects: toxic bootleg liquor, corruption, bribery, and binge drinking. Colorado voters suspended the state's Prohibition laws on July 1, 1933, and while racism and discrimination against a new wave of Mexican immigrants and African-American migrants persisted, the KKK was never again a significant force in Colorado politics.

The Great Depression

When World War I ended, the economy continued to be strong for a short period. However, with less demand for goods, prices dropped and 1918 saw a short recession, followed by a more severe one between 1920 and 1921. The mining industry was hard hit by decreasing prices and increasing foreign competition during the post-war recession years. Coal mining in Colorado was particularly affected as alternative sources of fuel were widely adopted and labor strikes hurt production. In 1928 Denver was on the receiving end of a major natural gas pipeline from Texas and as more households and businesses switched to gas, the more demand for coal fell.[49]

1905 to 1929 saw the longest recorded wet period in Colorado history.[50] This favorable weather combined with war-time demand saw farmers over plant during World War I and significant price drops after the war ended caused many farmers significant losses.[20] Costs began to exceed profits and many farmers were forced to sell their land which was then rented to others or simply left abandoned. Dryland farming was common on the prairies though many farmers removed the native grasses that helped control erosion. In 1929 the national economy crashed leading to the Great Depression. In 1930 the weather turned dry beginning the most widespread and longest lasting drought in Colorado history, a period of time that would later be referred to as the "Dust Bowl."[50] Dry weather, soil erosion, and a depressed economy led to a huge social upheaval felt across the entire nation.

The Dust Bowl decimated agriculture and the Great Depression caused industries and mines to close, their workers laid off. Many of these unemployed came to Denver looking for work and a better life. It was estimated that in 1933 one in four Denverites was out of work. The Hoover administration promised that recession would be over quickly, but the economy continued to worsen, and Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election with his promise of a "New Deal". The New Deal brought funds and jobs to Colorado and to Denver. The Historic American Buildings Survey hired architects and photographers to document historic buildings and in the process inspired the nascent historic preservation movement. The Civilian Conservation Corps built trails and campgrounds in Denver's Mountain Parks. The Works Progress Administration build roads, fixed schools and funded artists to decorate government buildings. The new roads and trails encouraged tourism and combined with improvements rail and air travel made Denver a hub for transportation.[51][52]

In the mid-1920s Denver financed the Moffat Tunnel through the Rocky Mountains which, when it opened in 1928, shortened the distance between Denver and the Pacific coast by 176 miles (283 km). The tunnel opened just as rail travel was undergoing a transformation in the 1930s. The Burlington Railroad introduced the Zephyr in 1934 with a record-breaking 13 hours and 5 minutes trip from Denver to Chicago. It was a revolutionary new diesel-powered train, streamlined and luxurious, that changed the public's expectations of rail travel.[49] Having a direct link to the west coast helped Denver compete against Cheyenne and Pueblo for rail business and it quickly became a major hub for railways.[53] Denver was struck on August 3, 1933, with a major flood of Cherry Creek following the failure of the Castlewood Dam.[54][55][56]

Air travel was advancing around the same period. When mayor Benjamin F. Stapleton opened Denver Municipal Airport in 1929 it was derided as a taxpayer subsidy for the powerful elite who flew for sport. Built northeast of Denver The Denver Post complained that it was too far from the city center and the location had been chosen to benefit the mayor's financial backers. However, with four gravel runways, one hangar, and a terminal, it was greeted by others as "the West's best airport." At the time unpressurized planes were the norm, and transcontinental flights went through Cheyenne or south through Texas as the mountains were smaller there. Denver Municipal Airport was used mainly for mail service and private pilots. As pressurized planes came into general use, the mountains were no longer an issue and the advanced airport attracted major airlines positioning Denver as a major hub for air travel in the region.[49][51]

The economy began to recover at the end of the decade as World War II started in Europe and demand for goods increased. As America began to gear up for its entrance into the war, Denver was well positioned to benefit from the activity. Denver had been selected for a new training airbase, Lowry Air Force Base which opened in 1938, and in 1941 the Denver Ordnance Plant opened. These facilities brought many jobs with them which in turn attracted more people to the city. Denver had started the decade with just under 288,000 people and by 1940 had over 322,000.

World War II and after

Until World War II, Denver's economy was dependent mainly on the processing and shipping of minerals and ranch products, especially beef and lamb. Like the rest of the nation most Denverites were isolationists, but after the bombing of Pearl Harbor Denver joined the rest of the nation in the war effort. Denver's leaders continued their efforts to bring businesses to the city during the war and in the years following, specialized industries were introduced into the city, making it a major manufacturing center. One of Denver's selling points was its location away from either coast making an attack highly unlikely. The Rocky Mountain Arsenal, Buckley Air Force Base, and the Denver Ordnance Plant all opened during the war. In 1941 over 6500 federal employees lived and worked in Denver. With so many federal employees already in Denver, it was easier to convince the government to add more and by 1946, the number increased to over 16,000.[19]

After the war many of the facilities continued to be utilized or were converted to different uses, for example the Denver Ordnance Plant was converted into the Denver Federal Center. More federal agencies began to come to the area which already had a large federal footprint and a well trained work force. The Atomic Energy Commission, National Center for Atmospheric Research, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and National Institute of Standards and Technology all opened offices in the Denver area. From 1953 to 1989, the Rocky Flats Plant, a Department of Energy nuclear weapon facility formerly located about 15 miles (24 km) from Denver, produced fissile plutonium "pits" for nuclear warheads. A major fire at the facility in 1957, as well as leakage from nuclear waste stored at the site between 1958 and 1968, resulted in the contamination of some parts of Denver, to varying degrees, with plutonium-239, a harmful radioactive substance with a half-life of 24,200 years.[57] Studies have linked the contamination to an increase in birth defects and cancer incidence in central Denver and nearer Rocky Flats.[58][59] With the large military and federal presence in the area the aerospace industry followed. Large corporations such as IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Honeywell, Ball Aerospace, and Lockheed-Martin came to Denver. These businesses brought jobs and money with them and began to influence the city displacing the wealthy entrepreneurs and pioneer families that had previously dominated political life.[19]

In 1947, J. Quigg Newton was elected mayor and began the process of modernizing the government, expanding public housing, setting up one the nation's first civil rights commissions. At the time restrictive racial covenants were common in every major city in the country. Long before the Civil Rights Acts were enacted, the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission passed one of the earliest fair housing laws in the nation permitting Mexican-Americans, African-Americans, Japanese-Americans, and Jews to move into neighborhoods previously denied to them. These new laws upset many and contributed to the flight of middle-class families to the suburbs. Despite these laws, discrimination was still prevalent, but the work of the Newtons's Human Rights and Community Relations spared Denver some of the racial unrest that occurred in other cities in the post-war years.[19][60]

Over four million soldiers had come through Denver during the war for training or recuperation and after the war ended many chose to make Denver their home. As Denver's population expanded rapidly, many old buildings were torn down to make way for new housing projects. The Denver Urban Renewal Authority demolished block after block to make room for apartments and parking lots. Many of Denver's finest buildings from the frontier era were demolished, including the Tabor Opera House, as the city expanded upward and outward. By 1950 middle-class families were moving away from the downtown area seeking larger houses and better schools; the suburbs multiplied as more people moved out of the city. In the 1960s Victorian homes were considered old-fashioned and unpopular and were targeted for demolition. The destruction of so many of these homes spurred Denverites to form the Denver Landmark Preservation Commission and Historic Denver, Inc which raised awareness of the value of these historic buildings and established the local historical preservation movement.[61]

During this time Denver was a gathering point for poets of the "beat generation." Beat icon Neal Cassady was raised on Larimer Street in Denver, and a portion of Jack Kerouac's beat masterpiece On the Road takes place in the city, and is based on the beat's actual experiences in Denver during a road trip. Beat poet Allen Ginsberg lived for a time in the Denver suburb of Lakewood, and he helped found the Buddhist college, Naropa University or the "Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa" in nearby Boulder.

Denver was also a gathering place for a new Chicano Movement. In March 1969, a convention hosted by Rodolfo Gonzales's Crusade for Justice was held in Denver and the Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was adopted as a manifesto for the movement. The Crusade for Justice was instrumental in bringing attention to the plight of Mexican-Americans living in Denver and laid the ground work for Hispanics to be in city government.[61][62]

Downtown boom and suburban growth

After World War II, oil and gas companies opened offices in Denver because of its proximity to the mountains and the energy fields contained within. As the price of oil and gas rose during the 1970s energy crisis these companies fueled a skyscraper boom in the downtown area. A second office core was opened in the suburban Denver Tech Center to accommodate the increasing demand for office space. Many original downtown saloons and old buildings were renovated and revitalized. While many other cities at the time were threatened by crime and bankruptcy Denver was actively growing and renewing its downtown.[19]

In 1969 the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that 'optional' attendance zones constituted segregation and ordered schools to be de-segregated. This triggered the dynamiting of school vehicles and fire-bombing of school buildings. Denver complied with the law by annexing neighboring towns and busing students. By the mid-1970s many wealthy residents were leaving Denver. In 1974 anti-integrationists used the fears about the impact of racial mixing as well as the recent tensions between Denver and its neighbors to pass the Poundstone Amendment to the state constitution. Its supporters claimed the amendment would prevent Denver from abusing its size and status, while detractors pointed out that it greatly limited the ability of the city to absorb other school districts and thus end segregation in its schools.[62]

With the combined spending of the energy companies and the federal government, Denver expanded quickly. Denver went from having a small urban core surrounded by rural farms to a booming downtown dotted with skyscrapers and surrounded by growing suburbs. The majority of the new people settled in the suburbs; Denver's population was essentially flat at about 490,000 from 1960 to 1980 even as the land area grew by 40 square miles (100 km2). With the expansion came problems. Traffic increased due to poor public transportation and pollution increased due to traffic.[19]

Denver Tramway had been responsible for all public transportation in Denver since the turn of the century, but with aging equipment, low revenues, and lackluster ridership it eventually dissolved. Author Sherah Collins writes, "... in 1970, Denver had more cars per capita than any other place in the country, which is not surprising due to the lack of public transit options."[63] In 1974 the Regional Transportation District took over responsibility for Denver's public transportation. During this period a "brown cloud" began to form over the Front Range, a result of air pollution from the increasing number of cars and people in the area. This cloud of pollution would take more than two decades to get rid of and was a serious concern for people living in the Denver area.[64]

Many people had moved to Denver for the beautiful landscapes and climate. The environment had always been an important issue to Coloradans and when Denver was selected to host the 1976 Winter Olympics to coincide with Colorado's centennial anniversary, a movement against hosting the games was formed based largely on concerns around the environmental impact of having so many people come to the area. Colorado voters struck down ballot initiatives allocating public funds to pay for the high costs of the games, and they were subsequently moved to Innsbruck, Austria. The movement against hosting the games was led by then State Representative Richard Lamm who was subsequently elected as Colorado governor in 1974.[65]

With the 1979 energy crisis the price of oil rose to over $30 a barrel, but by the mid-1980s the price had slid to under $10 a barrel. Thousands of oil and gas industry workers lost their jobs and unemployment rates soared. Downtown Denver had been overbuilt over the past two decades and the cost of office space dropped as office vacancy rates grew to the highest in the nation at 30-percent. Housing prices fell, the exodus from the city to the suburbs continued and the city fell into disrepair. By 1990 the population of the city had fallen to 467,610 the lowest level in over 30 years.[51]

Recession and new growth

In 1983, Federico Peña became the city's first Latino mayor. One of his central campaign messages was a promise of inclusiveness targeted at minorities. Latino turnout reached 73% in 1983, a contrast to the usually low Latino rates elsewhere. When the economic downturn happened in the mid-1980s, Peña convinced Denverites to reinvest billions in their city even though many critics complained that taking loans in the middle of a recession was foolish. Under the leadership of Peña voters approved a $3 billion airport, the $126 million Colorado Convention Center, a $242 million bond for infrastructure, a $200 million bond for Denver Public Schools, and a 0.1 per cent sales tax to build a new baseball stadium for the Colorado Rockies. Many people worried that Denver was on the wrong track when the city's total bonded indebtedness peaked at over $1 billion.[66]

Mayor Peña worked together with the surrounding suburbs to market Denver as a vibrant city. Using the special tax district model exemplified by the Regional Transportation District, a Scientific and Cultural Facilities District was set up and a 0.1 per cent sales tax was approved by voters to help fund artistic, cultural, and scientific organizations in the Denver metropolitan area. In 1995, these organizations attracted over 7.1 million visitors. One of Peña's signature achievements was the laying of the foundation for Denver International Airport.[66]

In 1957 Denver's original airport, Stapleton International Airport, was the eighth busiest in the nation. By the mid-1980s it had become the seventh largest airport in the world and fourth busiest in the United States. When it was initially built 3 miles (4.8 km) east of downtown it was in the middle of farmland, but as the decades passed the city began to surround it and Stapleton no longer had any room to expand. The Colorado General Assembly brokered a deal to annex land from Adams County to Denver County for the new airport, increasing Denver's size by 53 square miles (140 km2) in the single largest annexation in the city's history. Despite opening two years late and shuttering a much hyped automated baggage system, Denver International Airport is widely considered a success and has contributed significantly to economy of the region.[67][68]

In 1991, at a time when the city was 12% Black and 20% Latino, Wellington Webb won a come-from-behind victory as the city's first black mayor. The Hispanic and Black minority communities supported the candidate at 75-85% levels.[69] Webb, who also won 44% of the white vote, reached out to the business community, promoting downtown economic development and major projects such as the new airport, Coors Field, and a new convention center. During his administration, Denver built the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library in the historic Five Points neighborhood, and helped pass several neighborhood bonds for infrastructure improvements citywide.

At the end of the eighties Denver's economy started to grow. In 1989 unemployment dropped to 5.3 percent, down from a high of 9.7 percent in 1982. Pollution-control measures came into force, helping to eliminate the noxious "brown cloud" that had hung over the city. "Lower Downtown", formerly a warehouse district, was renovated and became a focal point for new urban development. With office space in Denver the cheapest in the world, many local companies began locking in long-term leases, which kept those companies in Denver and began to drive prices back up. As inventories emptied out and prices stabilized from speculation of earlier years, Colorado's climate and well educated labor force began to bring people and business back to the area.[70]

As the economy grew so did the population. Many Denverites left the city for the greater space offered by the suburbs, but for each citizen lost, others came from out of state to settle in their place. Traffic grew and many people from the suburbs moved out to rural areas. This situation of urban sprawl was a cause of concern, and the Sierra Club ranked the Denver metro area among its 10 worst offenders. In 1999, Colorado residents ranked growth as the state's number one problem.[71] That same year Denver metro area voters approved two property-tax increases to help fund the Transportation Expansion (T-REX) project, which reconstructed congested highways and laid light-rail tracks between downtown and the Tech Center, both of which were made possible through the leadership of the Regional Transportation Districts's CEO at the time, Clarence William Marsella. Colorado's population had expanded from 3.1 million at the beginning of the 1990s to over 4 million by the end, and Denver closed out the decade with more than 554,000 people.

21st century

With Denver experiencing so much growth, the large scale transportation projects undertaken by the Regional Transportation District under the leadership of Clarence Marsella, needed to be successful. Fortunately, T-REX was completed in November 2006, 22 months ahead of schedule. The success of T-REX led to public support for the FasTracks expansion project in 2004. These projects helped to alleviate some of the worst traffic congestion in the metro area, allowing for continued growth.

Through the late 1990s the majority of Denver's economy was concentrated in a few key sectors: energy, government and the military, technology, and agriculture. Over the next decade Denver and Colorado attracted new industries and the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade (OEDIT) says the state now has 14 core industries including health care, financial services and tourism. This diversification of the economy helped cushion the city and state from the global recession of 2008-2010. The fact that Denver's tax base is made up mostly of sales and income tax meant that it felt the economic downturn faster than others, but this meant it also recovered more quickly, helping Denver weather the recession better than many other U.S. cities reliant mainly on property taxes.[72][73]

Businessman John Hickenlooper was elected mayor in 2003 and reelected in 2007 with 87% of the vote. After he was elected governor of Colorado in 2011, Michael Hancock was elected Denver's second African American mayor.

See also

- Timeline of Denver

- Outline of Colorado

- Index of Colorado-related articles

- Historic Colorado counties

- List of mayors of Denver

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Denver, Colorado

- Pike's Peak Gold Rush

References

- Gehling, Richard (2006). "The Pike's Peak Gold Rush". Archived from the original on 2008-06-28. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- Brown 1985

- Barnhouse 2012

- King 1911

- Gallagher, Jolie (2011). A Wild West History of Frontier Colorado (First ed.). Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781609491956.

- Gallagher, p. 2

- Gallagher, pp.2

- Noel, Tom. "Early Denver History - "A Rough and Tumble Place"". Visit Denver. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Daughters of the American Revolution (1917). "Denver Chapter, by Grace Deisher, Historian". Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine. 51 (Public domain ed.). New York City: R.R. Bowker Co.

- Larimer 1918

- "Early Denver History - Denver's Beginnings". Visit Denver. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- Smiley 1901

- "An Act to provide a temporary Government for the Territory of Colorado" (PDF). Thirty-sixth United States Congress. 1861-02-28. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- "State Government History". State of Colorado, Department of Personnel & Administration, Colorado State Archives. April 18, 2001. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- "Colorado Municipal Incorporations". State of Colorado, Department of Personnel & Administration, Colorado State Archives. December 1, 2004. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- Thomas J. Noel. "Denver History - 2. The Golden Gamble". DenverGov. Archived from the original on October 16, 2009. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- Leonard 1990

- A. H. Koschman and M. H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.86.

- Baker 2004

- Ubbelohde 2006

- Leonard 1990, pp. 44–45

- "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1890". United States Census Bureau. June 15, 1998. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- "The Ballad of Baby Doe Opera Houses Gallery".

- Baker 2004, pp. 39–48

- Secrest 2002

- Wallace 2011

- Thompson 1999

- Bonner 2004, p. 370

- "United Way History". Archived from the original on 2008-04-29. Retrieved 2013-04-01.

- Denton 1997

- Abrams 2007

- Baker 2004, pp. 51–55

- Everett 2005, p. 76

- Leonard 1990, p. 103

- Ubbelohde 2006, p. 217

- Dupont, Brandon (Aug 6, 2012). "The Slow Recovery from the 1890s Recession". Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- Cotton, Jean. "The Silver Crash of 1893: Lore, Legend and Fact". Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- Smith 2009, pp. 294–316

- "Some Things Denver Owes to Speer". Rocky Mountain News. 15 May 1918. p. 3.

- "1908's Hot Ticket was to DNC".

- Campbell 1976

- Webb 2007, pp. 82,189,366

- Boyer 1975, p. 174

- Goldman 1970, p. 534

- Brundage 1994, pp. 161–162

- Thomas J. Noel. "Mile High City - 4. Immigrants". DenverGov. Archived from the original on July 29, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- Lerner 2007, pp. 96–97

- Goldberg 1981

- "Land of Contrast: A History of Southeast Colorado". BLM Cultural Resources Series. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- McKee, Thomas B.; Doesken, Nolan J.; Kleist, John; Shrier, Catherine J. (2000), A History of Drought in Colorado; Lessons Learned and What Lies Ahead (PDF), Colorado Water Resources Research Institute, Colorado State University

- Thomas J. Noel. "Mile High City - 7. Denver's ups and downs". DenverGov. Archived from the original on October 16, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- "The New Deal in Colorado: 1933-1942" (PDF). Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Colorado Historical Society. August 13, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- Bollinger 1979

- Cherry Creek Flood, 1933, Denver Public Library, Western History and Genealogy Division, 2015.

- Castlewood Canyon State Park: A brief history, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, State of Colorado, 2007].

- Disaster Nearly Drowns Denver In 1933, Ion Colorado, 1 February 2019.

- Moore 2007

- Iversen, Kristen (March 10, 2012). "Fallout at a Former Nuclear Weapon Plant". The New York Times.

- Johnson, Carl J. (October 1981). "Cancer Incidence in an Area Contaminated with Radionuclides Near a Nuclear Installation". AMBIO. 10 (4): 176–182. JSTOR 4312671., cited in Moore 2007, pp. 103–109.

- Chaer Robert. "Our History - Human Rights and Community Relations".

- Grace 2007

- Romero 2005

- Collins 2008

- "Decade after 'brown cloud,' Denver's air clears". USA Today. August 10, 2002. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- "Colorado only state ever to turn down Olympics". Denver Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Thomas J. Noel. "Imagine a Great City". DenverGov. Archived from the original on December 31, 2009. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- William Celis (Feb 28, 1997). "Two years later, Denver International is a runway success". USA Today.

- Ken Schroeppel (November 25, 2012). "Denver's Single-Family Homes by Decade: Conclusion". DenverUrbanism.com. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- Kaufmann 2003

- Donald Blount. "'80s downturn spurred state to scale new peaks". The Denver Post. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- David Olinger (February 7, 1999). "We caused sprawl ourselves". The Denver Post. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- Paula Moore (September 27, 2013). "What really happened on the way to 2013?". The Denver Business Journal. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- Staff (November 12, 2013). "Study finds Denver had faster recovery from recession". The Denver Business Journal. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

Bibliography

- Abrams, Jeanne (2007). Jewish Denver : 1859-1940. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 9780738548296.

- Arrington, Leonard J.; Alley, Jr., John R. (1992). Harold F. Silver: Western Inventor, Businessman, and Civic Leader. Utah State University Press. ISBN 9780874211597.

- Baker, Gayle (2004). Denver, A BoomTown History. Santa Barbara, CA: HarborTown Histories. ISBN 0971098441.

- Barnhouse, Mark (2012). Northwest Denver. Charleston, S.C: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 9780738589022.

- Barth, Gunther Paul (1975). Instant Cities: Urbanization and the Rise of San Francisco and Denver. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195018998.

- Bollinger, Edward (1979). Rails that climb : a narrative history of the Moffat Road. Golden: Colorado Railroad Museum. ISBN 9780918654298.

- Bonner, Jeremy (2004). "Religion". In Newby, Rick (ed.). Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Regional Cultures: The Rocky Mountain Region. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313328176.

- Boyer, Richard Owen; Morais, Herbert Montfort (1975). Labor's Untold Story (reprint ed.). United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers of America. ISBN 9780916180010.

- Brosnan, Kathleen A. (2002). Uniting Mountain and Plain: Cities, Law, and Environmental Change along the Front Range. UNM Press. ISBN 9780826323521.

- Brown, Robert L. (1985). The Great Pike's Peak Gold Rush. Caxton Press. ISBN 9780870045332.

- Brundage, David Thomas (1994). The Making of Western Labor Radicalism: Denver's Organized Workers, 1878-1905. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252020759.

- Campbell, D'Ann (1976). "Judge Ben Lindsey and the Juvenile Court Movement, 1901-1904". Arizona and the West. University of Arizona Press. 18: 5–20. ISSN 0004-1408.

- Carver, Sharon Snow (2000). Club Women of the Three Intermountain Cities of Denver, Boise and Salt Lake City between 1893 and 1929 (Ph.D.). Brigham Young University. DAI 61(5): 2000-A. DA9972727.

- Collins, Sherah (2008). Aurora. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 9780738548241.

- Denton, James A. (1997). Rocky Mountain Radical: Myron W. Reed, Christian Socialist. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826318145.

- Dickson, Lynda Fayes (1982). The Early Club Movement among Black Women in Denver: 1890-1925 (Ph.D.). University of Colorado, Boulder. DAI 1982 43(6): 2115-2116-A. DA8221063.

- Dorsett, Lyle (1986). The Queen City: A History of Denver. Pruett Publishing Company. ISBN 9780871087041.

- Edwards, Susan Jane (1994). Nature as Healer: Denver, Colorado's Social and Built Landscapes of Health, 1880-1930 (Ph.D.). University of Colorado, Boulder. DAI 1995 55(10): 3283-A. DA9506327.

- Foster, Mark S (1991). Henry M. Porter: Rocky Mountain Empire Builder. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870812323.

- Goldberg, Robert (1981). Hooded empire : the Ku Klux Klan in Colorado. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252008481.

- Goldman, Emma (1970). Living My Life (reprint ed.). Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486225449.

- Goodstein, Phil H. (2003). Denver from the Bottom Up: From Sand Creek to Ludlow. New Social Publications. ISBN 9780962216992.

- Goodstein, Phil H. (1999). Denver in our time: A people's history of the modern Mile High City. New Social Publications. ISBN 9780962216978.

- Grace, Stephen (2007). It happened in Denver. Guilford, Conn: TwoDot. ISBN 9780762741298.

- Gutfreund, Owen D. (2004). Twentieth-Century Sprawl: Highways and the Reshaping of the American Landscape. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198032427.

- Hendricks, Rickey; Foster, Mark S. (1994). For a Child's Sake: History of the Children's Hospital, Denver, Colorado, 1910-1990. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870813498.

- Hero, Rodney (1987). "The Election of Hispanics in City Government: An Analysis of the Election of Federico Peña as Mayor of Denver". Western Political Quarterly. 40 (March): 93–105. doi:10.1177/106591298704000108.

- Hero, Rodney; Beatty, Kathleen (1989). "The Election of Frederico Peña as Mayor of Denver: Analysis and Implications". Social Science Quarterly. 70 (June): 300–310.

- Hungerford, Edward (1913), "American Paris", The Personality of American Cities, New York: McBride, Nast & Company

- Jones, William C.; Forrest, Kenton (1993). Denver: A Pictorial History from Frontier Camp to Queen City of the Plains (3rd ed.). Colorado Railroad Museum. ISBN 9780918654496.

- Kaufmann, Karen Malmuth (1998). Voting in American Cities: The Group Interest Theory of Local Voting Behavior (Ph.D.). University of California, Los Angeles. DAI 1999 59(9): 3629-A. DA9906182.

- Kaufmann, Karen M. (2003). "Black and Latino Voters in Denver: Responses to Each Other's Political Leadership". Political Science Quarterly. Academy of Political Science. 118 (1): 107–125. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165x.2003.tb00388.x. ISSN 0032-3195.

- Kelly, George V. (1974). The Old Gray Mayors of Denver. Pruett Publishing Company. ISBN 9780871080783.

- King, Clyde Lyndon (1911). The history of the government of Denver with special reference to its relations with public service corporations. Denver, Colorado: The Fisher Book Company.

- Knapp, Anne Curtis (1983). Making an Orderly Society: Criminal Justice in Denver, Colorado, 1858-1900 (Ph.D.). University of California, San Diego. DAI 1984 44(11): 3467-A. DA8405206.

- Larimer, William Henry Harrison (1918). Herman Stearns Davis (ed.). Reminiscences of General William Larimer and of his son William H. H. Larimer, two of the founders of Denver city. Press of the New Era Printing Co.

- Leonard, Stephen J.; Noel, Thomas J. (1990). Denver: Mining Camp to Metropolis. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780585101255.

- Lerner, Michael A. (2007). Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674024328.

- Ling, Richard Seyler (1984). The Social Construction of Synthetic Charisma: A Sociological Examination of the 1983 Denver Mayoral Campaign (Ph.D.). University of Colorado, Boulder. DAI 1985 45(7): 2261-A. DA8422625.

- Miller, Jeff (1983). Stapleton International Airport: The First Fifty Years. Pruett Publishing Company. ISBN 9780871086143.

- Mitchell, J. Paul (1977). "Taming the Urban Frontier: Denver during the Progressive Era". In Hoover, Dwight W.; Koumoulides, John T.A. (eds.). Conspectus of History: Cities in History. 1.4. Ball State University. pp. 24–33.

- Moore, LeRoy (2007). "Democracy and Public Health at Rocky Flats: The Examples of Edward Martell and Carl J. Johnson". In Quigley, Dianne; Lowman, Amy; Wing, Steve (eds.). Ethics of Research on Health Impacts of Nuclear Weapons Activities in the United States (PDF). Collaborative Initiative for Research Ethics and Environmental Health (CIREEH) at Syracuse University. pp. 55–97. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- Morley, Judy Mattivi (2006). Historic Preservation and the Imagined West: Albuquerque, Denver, and Seattle. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700614776.

- Noel, Thomas J. (1996). The City and the Saloon: Denver, 1858-1916. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870814266.

- Noel, Thomas J. (1989). Colorado Catholicism and the Archdiocese of Denver, 1857-1989. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870811791.

- Noel, Thomas J. (1996). Denver Landmarks & Historic Districts: A Pictorial Guide. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870814273.

- Noel, Thomas J. (1997). Mile high city: An illustrated history of Denver. Heritage Media Corporation. ISBN 9781886483101.

- Noel, Thomas J.; Norgren, Barbara S. (1987). Denver: The City Beautiful and Its Architects, 1893-1941. Historic Denver, Inc. ISBN 9780914248040.

- Peterson, Eric, ed. (2007). Frommer's Denver, Boulder & Colorado Springs. Wiley. ISBN 9780470125625.

- Pickering, John Richard (1978). Blueprint of Power: The Public Career of Robert Speer in Denver, 1898-1918 (Ph.D.). University of Denver. DAI 1979 39(11): 6920-A.

- Portrait and Biographical Record of Denver and Vicinity Colorado. Chapman Publishing Company. 1898.

- Reese, Carol McMichael (1992). The Politician and the City: Urban Form and City Beautiful Rhetoric in Progressive Era Denver (Ph.D.). University of Texas, Austin. DAI 1992 53(4): 969-A. DA9225704.

- Romero, Tom I. (2005). "Land, Culture, and Legal Exchange in Colorado's Mountains, Plains, and Deserts". In Lagayette, Pierre (ed.). Exchange: practices and representations. Presses de l'Universite de Paris-Sorbonne. pp. 125–170. ISBN 9782840503590. ISSN 1164-544X.

- Rose, Mark H. (1995). Cities of Light and Heat: Domesticating Gas and Electricity in Urban America. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271013497.

- Secrest, Clark (2002). Hell's Belles: Prostitution, Vice, and Crime in Early Denver, with a Biography of Sam Howe, Frontier Lawman (2nd ed.). University Press of Colorado. ISBN 9780870816338.

- Smiley, Jerome C. (1901). History of Denver: With Outlines of the Earlier History of the Rocky Mountain Country. Times-Sun Pub. Co. Archived from the original on 2013-01-28.

- Smith, Jeff (2009). Alias Soapy Smith: The Life and Death of a Scoundrel. Klondike Research. ISBN 9780981974316.

- Stefanco, Carolyn J. (1987). Pathways to Power: Women and Voluntary Associations in Denver, Colorado, 1876-1893 (Ph.D.). Duke University. DAI 1988 49(4): 932-933-A. DA8810886.

- Taylor, Mary Jean (1990). Leadership Responses to Desegregation in the Denver Public Schools: A Historical Study, 1959-1977 (Ph.D.). University of Denver. DAI 1990 51(6): 1866-A. DA9030097.

- Thompson, Jennifer A. (1999). "From Travel Writer to Newspaper Editor: Caroline Churchill and the Development of Her Political Ideology Within the Public Sphere". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. University of Nebraska Press. 20 (3): 42–63. doi:10.2307/3347220. ISSN 0160-9009. JSTOR 3347220.

- Ubbelohde, Carl (2006). A Colorado history. Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing Co. ISBN 9780871089427.

- Wallace, Elizabeth (2011). Hidden history of Denver. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 9781609493509.

- Webb, Wellington E.; Brovsky, Cindy (2007). Wellington Webb: The Man, the Mayor, and the Making of Modern Denver. Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 9781555916343.

External links

- City and County of Denver website

- 1905 magazine article with photos

- Digital Public Library of America. Items related to Denver, various dates