History of film

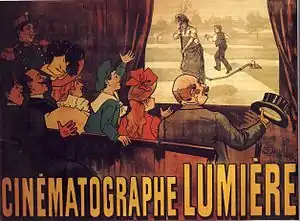

Although the start of the history of film as an artistic medium is not clearly defined, the commercial, public screening of ten of Lumière brothers' short films in Paris on 28 December 1895 can be regarded as the breakthrough of projected cinematographic motion pictures. There had been earlier cinematographic results and screenings by others, but they lacked either the quality, financial backing, stamina or the luck to find the momentum that propelled the cinématographe Lumière into a worldwide success.

| Part of a series on |

| Filmmaking |

|---|

|

| Glossary |

|

| Years in film |

|---|

|

| 1870s |

Soon film production companies and studios were established all over the world. The first decade of motion picture saw film moving from a novelty to an established mass entertainment industry. The earliest films were in black and white, under a minute long, without recorded sound and consisted of a single shot from a steady camera.

Conventions toward a general cinematic language developed over the years with editing, camera movements and other cinematic techniques contributing specific roles in the narrative of films.

Special effects became a feature in movies since the late 1890s, popularized by Georges Méliès' fantasy films. Many effects were impossible or impractical to perform in theater plays and thus added more magic to the experience of movies.

Technical improvements added length (reaching 60 minutes for a feature film in 1906), synchronized sound recording (mainstream since the end of the 1920s), color (mainstream since the 1930s) and 3D (mainstream in theaters in the early 1950s and since the 2000s). Sound ended the necessity of interruptions of title cards, revolutionized the narrative possibilities for filmmakers, and became an integral part of moviemaking.

Popular new media, including television (mainstream since the 1950s), home video (mainstream since the 1980s) and internet (mainstream since the 1990s) influenced the distribution and consumption of films. Film production usually responded with content to fit the new media, and with technical innovations (including widescreen (mainstream since the 1950s), 3D and 4D film) and more spectacular films to keep theatrical screenings attractive.

Systems that were cheaper and more easily handled (including 8mm film, video and smartphone cameras) allowed for an increasing number of people to create films of varying qualities, for any purpose (including home movies and video art). The technical quality was usually lower than that of professional movies, but improved with digital video and affordable high quality digital cameras.

Improving over time, digital production methods became more and more popular during the 1990s, resulting in increasingly realistic visual effects and popular feature-length computer animations.

Different film genres emerged and enjoyed variable degrees of success over time, with huge differences between for instance horror films (mainstream since the 1890s), newsreels (prevalent in U.S. cinemas between the 1910s and the late 1960s), musicals (mainstream since the late 1920s) and pornographic films (experiencing a Golden Age during the 1970s).

1880s

Film as an art form has drawn on several earlier traditions in the fields such as (oral) storytelling, literature, theatre and visual arts. Forms of art and entertainment that had already featured moving and/or projected images include:

- shadowgraphy, probably used since prehistoric times

- camera obscura, a natural phenomenon that has possibly been used as an artistic aid since prehistoric times

- shadow puppetry, possibly originated around 200 BCE in Central Asia, India, Indonesia or China

- magic lantern, developed in the 1650s, preceded by some incidental and/or inferior projectors

- stroboscopic "persistence of vision" animation devices (phénakisticope since 1832, zoetrope since 1866, flip book since 1868)

Some ancient sightings of gods and spirits may have been conjured up by means of (concave) mirrors, camera obscura or unknown projectors. By the 16th century, necromantic ceremonies and the conjuring of ghostly apparitions by charlatan "magicians" and "witches" seemed commonplace.[1] The very first magic lantern shows seem to have continued this tradition with images of death, monsters and other scary figures.[2] Around 1790, the stories developed into multi-media ghost shows known as phantasmagoria. These shows could feature mechanical slides, rear projection, mobile projectors, superimposition, dissolves, live actors, smoke (sometimes to project images upon), odors, sounds and even electric shocks.[3][4] While the first magic lantern images seem to have been intended to scare audiences, soon more subjects appeared and the lantern was used not only for storytelling, but for education as well.[5] In the 19th century, a number of new and popular magic lantern techniques were developed, including dissolving views and several types of mechanical slides that created dazzling abstract effects (chromatrope, etc.) or that showed, for instance, falling snow, or the planets and their moons revolving.

Narrative predecessors

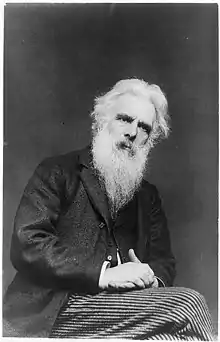

Early photographic sequences, known as chronophotography, lacked any serious narrative form. Most of these sequences were not initially intended to be viewed in motion and were instead presented as a serious, even scientific, method of studying movement. The sequences almost exclusively involved humans or animals performing a simple movement in front of the camera.[6] Starting in 1873, photographer Eadweard Muybridge began making hundreds of chronophotographic studies of the motion of animals and humans in real-time. He was soon followed by other chronophotographers like Étienne-Jules Marey, Georges Demenÿ and Ottomar Anschütz. In 1878, Muybridge published the first results of his studies as The Horse in Motion cabinet cards. Using a device known as a zoetrope, viewers would place the silhouette-like photographic images and watch them in motion. Long after the introduction of cinema, Muybridge's recordings would occasionally be animated into very short films with fluent motion (relatively often the footage can be presented as a loop that repeats the motion seamlessly).[7]

In the 1890s, films were seen mostly via temporary storefront spaces and traveling exhibitors or as "dumb" acts in vaudeville programs.[8] A film could be under a minute long and would usually present a single scene, authentic or staged, of everyday life, a public event, a sporting event or slapstick. There was little to no cinematic technique, the film was usually black and white and it was without sound.

In the years that followed, the art of the motion picture quickly went from a novelty act to an established large-scale entertainment industry. Films evolved from a single shot, completely made by one person with a few assistants, towards pictures that were several minutes in length and consisted of several shots and a narrative.

The novelty of realistic moving photographs was enough for a motion picture industry to blossom before the end of the century, in countries around the world. "The Cinema" was to offer a relatively cheap and simple way of providing entertainment to the masses. Filmmakers could record actors' performances, which then could be shown to audiences around the world. Travelogues would bring the sights of far-flung places, with movement, directly to spectators' hometowns. Movies would become the most popular visual art form of the late Victorian age.[9]

The Berlin Wintergarten theater hosted an early movie presentation in front of an audience, shown by the Skladanowsky brothers in 1895. The Melbourne Athenaeum started to screen movies in 1896. Movie theaters became popular entertainment venues and social hubs in the early 20th century, much like cabarets and other theaters.

Early Silent era

Until 1927, most motion pictures were produced without sound. This period is commonly referred to as the silent era of film.[10][11] To enhance the viewers' experience, silent films were commonly accompanied by live musicians in an orchestra, a theatre organ, and sometimes sound effects and even commentary spoken by the showman or projectionist.[12] In most countries, intertitles came to be used to provide dialogue and narration for the film, thus dispensing with narrators, but in Japanese cinema, human narrators known as benshi remained popular throughout the silent era.[13] The technical problems were resolved by 1923.

Illustrated songs were a notable exception to this trend that began in 1894 in vaudeville houses and persisted as late as the late 1930s in film theaters.[14] Live performance or sound recordings were paired with hand-colored glass slides projected through stereopticons and similar devices. In this way, song narrative was illustrated through a series of slides whose changes were simultaneous with the narrative development. The main purpose of illustrated songs was to encourage sheet music sales, and they were highly successful with sales reaching into the millions for a single song. Later, with the birth of film, illustrated songs were used as filler material preceding films and during reel changes.[15]

The 1914 film, The Photo-Drama of Creation was a non-commercial attempt to combine the motion picture with a combination of slides and synchronize the resulting moving picture with audio. The film included hand-painted slides as well as other previously used techniques. Simultaneously playing the audio while the film was being played with a projector was required. Produced by the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania (Jehovah's Witnesses), this eight–hour bible drama was being shown in 80 cities every day and almost eight million people in the United States and Canada saw the presentation.[16]

Birth of movies

Within several years of the rise of the motion picture, the films moved from a novelty show to an established large-scale entertainment industry. Films moved from a single shot, completely made by one person with a few assistants, towards films several minutes long consisting of several shots, which were made by large companies in something like industrial conditions.

By 1900, the first motion pictures that can be considered "films" – emerged, and film-makers began to introduce basic editing techniques and film narrative.[17]

Invention and advancement of cinematography

Early movie cameras were fastened to the head of a tripod with only simple levelling devices provided. These cameras were effectively fixed during the course of a shot, and the first camera movements were the result of mounting a camera on a moving vehicle. Although the exact timing is unknown, around early 1895, Auguste and Louis Lumière began filming 10 short sequences using their newly created cinématographe for exhibition to the public.[18] The sequences, which lasted roughly fifty seconds each, depicted daily life, both in France and across the globe.[19]

The first rotating camera for taking panning shots was built by Robert W. Paul in 1897, on the occasion of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. He used his camera to shoot the procession in one shot. His device had the camera mounted on a vertical axis that could be rotated by a worm gear driven by turning a crank handle, and Paul put it on general sale the next year. Shots taken using such a "panning" head were also referred to as 'panoramas' in the film catalogues.[20]

Georges Méliès, a former magician who "become involved with film as a way to further his obsession with illusion" and who is seen as "the godfather of special effects", built one of the first film studios in May 1897.[21] It had a glass roof and three glass walls constructed after the model of large studios for still photography, and it was fitted with thin cotton cloths that could be stretched below the roof to diffuse the direct rays of the sun on sunny days.[22]

Beginning in 1896, Méliès would go on to produce, direct, and distribute over 500 short films. The majority of these films were short, one-shot films completed in one take. Méliès drew many comparisons between film and the stage, which was apparent in his work. He realized that film afforded him the ability (via his use of time lapse photography) to "produce visual spectacles not achievable in the theater.[23]

The Execution of Mary Stuart, produced by the Edison Company for viewing with the Kinetoscope, showed Mary Queen of Scots being executed in full view of the camera. The effect was achieved by replacing the actor with a dummy for the final shot.[24][25] The technique used in the film is seen as one of the earliest known uses of special effects in film.[26] Georges Méliès also utilized this technique in the making of Escamotage d'un dame chez Robert-Houdin (The Vanishing Lady). The woman is seen to vanish through the use of stop motion techniques.[27]

The other basic technique for trick cinematography was the double exposure of the film in the camera. This was pioneered by George Albert Smith in July 1898 in England. The set was draped in black, and after the main shot, the negative was re-exposed to the overlaid scene. His The Corsican Brothers was described in the catalogue of the Warwick Trading Company in 1900: "By extremely careful photography the ghost appears *quite transparent*. After indicating that he has been killed by a sword-thrust, and appealing for vengeance, he disappears. A 'vision' then appears showing the fatal duel in the snow.”[28]

G.A. Smith also initiated the special effects technique of reverse motion. He did this by repeating the action a second time, while filming it with an inverted camera, and then joining the tail of the second negative to that of the first.[29] The first films made using this device were Tipsy, Topsy, Turvy and The Awkward Sign Painter. The earliest surviving example of this technique is Smith's The House That Jack Built, made before September 1900.

Cecil Hepworth took this technique further, by printing the negative of the forwards motion backwards frame by frame, so producing a print in which the original action was exactly reversed. To do this he built a special printer in which the negative running through a projector was projected into the gate of a camera through a special lens giving a same-size image. This arrangement came to be called a "projection printer", and eventually an "optical printer".

The use of different camera speeds also appeared around 1900 in the films of Robert W. Paul and Hepworth. Paul shot scenes from On a Runaway Motor Car through Piccadilly Circus (1899) with the camera turning very slowly. When the film was projected at the usual 16 frames per second, the scenery appeared to be passing at great speed. Hepworth used the opposite effect in The Indian Chief and the Seidlitz Powder (1901). The Chief's movements are sped up by cranking the camera much faster than 16 frames per second. This gives what we would call a "slow motion" effect.

Film editing and continuous narrative

The first films to consist of more than one shot appeared toward the end of the 19th century. A notable example was the French film of the life of Jesus Christ, La vie du Christ (The Birth, the Life and the Death of Christ),[30] by Alice Guy. These weren't represented as a continuous film, the separate scenes were interspersed with lantern slides, a lecture, and live choral numbers, to increase the running time of the spectacle to about 90 minutes. Another example of this is the reproductions of scenes from the Greco-Turkish war, made by Georges Méliès in 1897. Although each scene was sold separately, they were shown one after the other by the exhibitors. Even Méliès' Cendrillon (Cinderella) of 1898 contained no action moving from one shot to the next one. To understand what was going on in the film the audience had to know their stories beforehand, or be told them by a presenter.

Real film continuity, involving action moving from one sequence into another, is attributed to British film pioneer Robert W. Paul's Come Along, Do!, made in 1898 and one of the first films to feature more than one shot.[31] In the first shot, an elderly couple is outside an art exhibition having lunch and then follow other people inside through the door. The second shot shows what they do inside. Paul's 'Cinematograph Camera No. 1' of 1895 was the first camera to feature reverse-cranking, which allowed the same film footage to be exposed several times and thereby to create super-positions and multiple exposures. This technique was first used in his 1901 film Scrooge, or, Marley's Ghost.[32]

The further development of action continuity in multi-shot films continued in 1899 at the Brighton School in England.[33] In the latter part of that year, George Albert Smith made The Kiss in the Tunnel. This film started with a shot from a "phantom ride" at the point at which the train goes into a tunnel, and continued with the action on a set representing the interior of a railway carriage, where a man steals a kiss from a woman, and then cuts back to the phantom ride shot when the train comes out of the tunnel.[34] A month later, the Bamforth company in Yorkshire made a restaged version of this film under the same title, and in this case they filmed shots of a train entering and leaving a tunnel from beside the tracks, which they joined before and after their version of the kiss inside the train compartment.[35]

In 1900, continuity of action across successive shots was definitively established by George Albert Smith and James Williamson, who also worked in Brighton. In that year, Smith made As Seen Through a Telescope, in which the main shot shows a street scene with a young man tying the shoelace and then caressing the foot of his girlfriend, while an old man observes this through a telescope. There is then a cut to close shot of the hands on the girl's foot shown inside a black circular mask, and then a cut back to the continuation of the original scene.[36] Even more remarkable is James Williamson's 1900 film, Attack on a China Mission. The film, which film historian John Barnes later described as having "the most fully developed narrative of any film made in England up to that time", opens as the first shot shows Chinese Boxer rebels at the gate; it then cuts to the missionary family in the garden, where a fight ensues. The wife signals to British sailors from the balcony, who come and rescue them.[37] The film also used the first "reverse angle" cut in film history.[38]

G.A Smith pioneered the use of the close-up shot in his 1900 films, As Seen Through a Telescope and Grandma's Reading Glass.[36] He further developed the ideas of breaking a scene shot in one place into a series of shots taken from different camera positions over the next couple of years, starting with The Little Doctors of 1901 (the film, now thought lost, was remade as The Sick Kitten in 1903).[39] In a series of films he produced at this time, he also introduced the use of subjective and objective point-of-view shots, the creation of dream-time and the use of reversing. He summed up his work in Mary Jane's Mishap of 1903, with repeated cuts to a close shot of a housemaid fooling around. He combined these effects, along with superimpositions, use of wipe transitions to denote a scene change, and other devices, before going on to invent the Kinemacolor system of colour cinematography.[40][41] His films were the first to establish the basics of coherent narrative and what became known as film language, or "film grammar".[42][43]

James Williamson pioneered making films that had continuous action from shot to shot such as in his 1901 film Stop Thief!. The film is also revolutionary because it was one of the few films that did not use intertitles to convey its narrative.[44] Williamson experimented with the close-up, and made perhaps his most extreme test of the shot in The Big Swallow, when his character approaches the camera and appears to swallow it.[45] These two filmmakers of the Brighton School also pioneered the editing of the film; they tinted their work with color and used trick photography to enhance the narrative. By 1900, their films were extended scenes of up to 5 minutes long.[46]

Films of this period and genre were later termed "chase films".[47][48] These were inspired by James Williamson's Stop Thief! of 1901, which showed a tramp stealing a leg of mutton from a butcher's boy in the first shot, then being chased through the second shot by the butcher's boy and assorted dogs, and finally being caught by the dogs in the third shot.[44] Several British films made in the first half of 1903 extended the chase method of film construction. These included An Elopement à la Mode and The Pickpocket: A Chase Through London, made by Alf Collins for the British branch of the French Gaumont company, A Daring Daylight Burglary, made by Frank Mottershaw at the Sheffield Photographic Company, and Desperate Poaching Affray, made by William Haggar. Haggar in particular innovated the first extant panning shots; the poachers are chased by gamekeepers and police officers and the camera pans along, creating a sense of urgency and speed.[49] His films were also recognised for their intelligent use of depth of staging and screen edges, while film academic Noël Burch praised Haggar's effective use of off-screen space.[50] He was also one of the first filmmakers to purposefully introduce violence for entertainment; in Desperate Poaching Affray, the villains are seen firing guns at their pursuers.

Other filmmakers took up all these ideas including the American Edwin S. Porter, who started making films for the Edison Company in 1901. Porter, a projectionist, was hired by Thomas Edison to develop his new projection model known as the Vitascope. Porter wanted to develop a style of filmmaking that would move away from the one-shot short films into a "story-telling [narrative]" style.[51] When he began making longer films in 1902, he put a dissolve between every shot, just as Georges Méliès was already doing, and he frequently had the same action repeated across the dissolves. His film, The Great Train Robbery (1903), had a running time of twelve minutes, with twenty separate shots and ten different indoor and outdoor locations. He used cross-cutting editing method to show simultaneous action in different places. The time continuity in The Great Train Robbery was actually more confusing than that in the films it was modeled on, but nevertheless it was a greater success than them due to its Wild West violence. The Great Train Robbery served as one of the vehicles that would launch the film medium into mass popularity.[51][52]

The Pathé company in France also made imitations and variations of Smith and Williamson's films from 1902 onwards using cuts between the shots, which helped to standardize the basics of film construction. The sheer volume of Pathé's production led to their filmmakers giving a further precision and polish to the details of film continuity.An influential French film of the period was Méliès's 14-minute-long A Trip to the Moon.[53] It was extremely popular at the time of its release, and is the best-known of the hundreds of films made by Méliès.[54] It was one of the first known science fiction films, and used innovative animation and special effects, including the well-known image of the spaceship landing in the Moon's eye.[55]

Early Animation

When cinematography was introduced, animation was familiar from various optical toys (in stroboscopic form), magic lantern shows (in mechanical form) and from Emile Reynaud's Pantomimes Lumineuses. It took over a decade before animation started to play a role in cinemas with stop motion short films like Segundo de Chomón's Le théâtre de Bob (1906) and J. Stuart Blackton's The Haunted Hotel (1907) as well as hand-drawn short animation films like Blackton's 1906 film Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (with some cut-out animation) and Émile Cohl's Fantasmagorie (1908).

The world's first animated feature film was El Apóstol (1917), made by Italian-Argentine cartoonist Quirino Cristiani utilizing cutout animation.[57][58] Cristiani also directed the first animated feature film with sound, Peludópolis, released with a vitaphone sound-on-disc synchronization system soundtrack. Unfortunately, a fire that destroyed producer Federico Valle's film studio incinerated the only known copies of the movies, and they are now considered lost films.[59][60]

Feature film

Films at the time were no longer than one reel, although some multi-reel films had been made on the life of Christ in the first few years of cinema. The first feature-length multi-reel film in the world was the 1906 Australian production called The Story of the Kelly Gang.[61]

It traced the life of the legendary infamous outlaw and bushranger Ned Kelly (1855–1880) and ran for more than an hour with a reel length of approximately 4,000 feet (1,200 m).[62] It was first shown at the Athenaeum Hall in Collins Street, Melbourne, Australia on 26 December 1906 and in the UK in January 1908.[63][64]

Maturation

Film business

The first successful permanent theatre showing only films was "The Nickelodeon", which was opened in Pittsburgh in 1905.[65] By then, there were enough films several minutes long available to fill a programme running for at least half an hour, and which could be changed weekly when the local audience became bored with it. Other exhibitors in the United States quickly followed suit, and within two years, there were 8,000 of these nickelodeons in operation across the United States.[65] The American experience led to a worldwide boom in the production and exhibition of films from 1906 onwards.

By 1907, purpose-built cinemas for motion pictures were being opened across the United States, Britain and France. The films were often shown with the accompaniment of music provided by a pianist, though there could be more musicians. There were also a very few larger cinemas in some of the biggest cities. Initially, the majority of films in the programmes were Pathé films, but this changed fairly quickly as the American companies cranked up production. The programme was made up of just a few films, and the show lasted around 30 minutes. The reel of film, of maximum length 1,000 feet (300 m), which usually contained one individual film, became the standard unit of film production and exhibition in this period. The programme was changed twice or more a week, but went up to five changes of programme a week after a couple of years. In general, cinemas were set up in the established entertainment districts of the cities. In 1907, Pathé began renting their films to cinemas through film exchanges rather than selling the films outright.

By about 1910, actors began to receive screen credit for their roles, and the way to the creation of film stars was opened. Films were increasingly longer, and began to feature proper plots and development.

The litigation over patents between all the major American film-making companies led to the formation of a trust to control the American film business, with each company in the trust being allocated production quotas (two reels a week for the biggest ones, one reel a week for the smaller). However, although 6,000 exhibitors signed up to the trust, about 2,000 others did not and began to fund new film producing companies. By 1912, the independents had nearly half of the market and the government defeated the trust by initiating anti-trust action at the same time.

In the early 20th century, before Hollywood, the motion picture industry was based in Fort Lee, New Jersey across the Hudson River from New York City.[66][67][68] In need of a winter headquarters, moviemakers were attracted to Jacksonville, Florida due to its warm climate, exotic locations, excellent rail access, and cheaper labor, earning the city the title of "The Winter Film Capital of the World."[69] New York-based Kalem Studios was the first to open a permanent studio in Jacksonville in 1908.[70] Over the course of the next decade, more than 30 silent film companies established studios in town, including Metro Pictures (later MGM), Edison Studios, Majestic Films, King-Bee Film Company, Vim Comedy Company, Norman Studios, Gaumont Studios and the Lubin Manufacturing Company. The first motion picture made in Technicolor and the first feature-length color movie produced in the United States, The Gulf Between, was also filmed on location in Jacksonville in 1917.

Jacksonville was especially important to the African American film industry. One notable individual in this regard is the European American producer Richard Norman, who created a string of films starring black actors in the vein of Oscar Micheaux and the Lincoln Motion Picture Company.[69] In contrast to the degrading parts offered in certain white films such as The Birth of a Nation, Norman and his contemporaries sought to create positive stories featuring African Americans in what he termed "splendidly assuming different roles."

Jacksonville's mostly conservative residents, however, objected to the hallmarks of the early movie industry, such as car chases in the streets, simulated bank robberies and fire alarms in public places, and even the occasional riot. In 1917, conservative Democrat John W. Martin was elected mayor on the platform of taming the city's movie industry.[69] By that time, southern California was emerging as the major movie production center, thanks in large part to the move of film pioneers like William Selig and D.W. Griffith to the area. These factors quickly sealed the demise of Jacksonville as a major film destination.

Another factor for the industry's move west was that up until 1913, most American film production was still carried out around New York, but due to the monopoly of Thomas A. Edison, Inc.'s film patents and its litigious attempts to preserve it, many filmmakers moved to Southern California, starting with Selig in 1909.[71][72] The sunshine and scenery was important for the production of Westerns, which came to form a major American film genre with the first cowboy stars, G.M. Anderson ("Broncho Billy") and Tom Mix. Selig pioneered the use of (fairly) wild animals from a zoo for a series of exotic adventures, with the actors being menaced or saved by the animals. Kalem Company sent film crews to places in America and abroad to film stories in the actual places they were supposed to have happened.[73] Kalem also pioneered the female action heroine from 1912, with Ruth Roland playing starring roles in their Westerns.[74]

In France, Pathé retained its dominant position, followed still by Gaumont, and then other new companies that appeared to cater to the film boom. A film company with a different approach was Film d'Art. Film d'Art was set up at the beginning of 1908 to make films of a serious artistic nature. Their declared programme was to make films using only the best dramatists, artists and actors. The first of these was L'Assassinat du Duc de Guise (The Assassination of the Duc de Guise), a historical subject set in the court of Henri III. This film used leading actors from the Comédie-Française, and had a special accompanying score written by Camille Saint-Saëns. The other French majors followed suit, and this wave gave rise to the English-language description of films with artistic pretensions aimed at a sophisticated audience as "art films". By 1910, the French film companies were starting to make films as long as two, or even three reels, though most were still one reel long. This trend was followed in Italy, Denmark, and Sweden.

In Britain, the Cinematograph Act 1909 was the first primary legislation to specifically regulate the film industry. Film exhibitions often took place in temporary venues and the use of highly flammable cellulose nitrate for film, combined with limelight illumination, created a significant fire hazard. The Act specified a strict building code which required, amongst other things, that the projector be enclosed within a fire resisting enclosure.[75]

Regular newsreels were exhibited from 1910 and soon became a popular way for finding out the news – the British Antarctic Expedition to the South Pole was filmed for the newsreels as were the suffragette demonstrations that were happening at the same time. F. Percy Smith was an early nature documentary pioneer working for Charles Urban and he pioneered the use of time lapse and micro cinematography in his 1910 documentary on the growth of flowers.[76][77]

New film producing countries

With the worldwide film boom, more countries now joined Britain, France, Germany and the United States in serious film production. In Italy, production was spread over several centres, with Turin being the first and biggest hub for film activity. There, Ambrosio was the first company in the field in 1905, and remained the largest in the country through this period. Its most substantial rival was Cines in Rome, which started producing in 1906. The great strength of the Italian industry was historical epics, with large casts and massive scenery. As early as 1911, Giovanni Pastrone's two-reel La Caduta di Troia (The Fall of Troy) made a big impression worldwide, and it was followed by even bigger glasses like Quo Vadis? (1912), which ran for 90 minutes, and Pastrone's Cabiria of 1914, which ran for two and a half hours.

Italian companies also had a strong line in slapstick comedy, with actors like André Deed, known locally as "Cretinetti", and elsewhere as "Foolshead" and "Gribouille", achieving worldwide fame with his almost surrealistic gags.

The most important film-producing country in Northern Europe up until the First World War was Denmark.[78] The Nordisk company was set up there in 1906 by Ole Olsen, a fairground showman, and after a brief period imitating the successes of French and British filmmakers, in 1907 he produced 67 films, most directed by Viggo Larsen, with sensational subjects like Den hvide Slavinde (The White Slave), Isbjørnejagt (Polar Bear Hunt) and Løvejagten (The Lion Hunt). By 1910, new smaller Danish companies began joining the business, and besides making more films about the white slave trade, they contributed other new subjects. The most important of these finds was Asta Nielsen in Afgrunden (The Abyss), directed by Urban Gad for Kosmorama, This combined the circus, sex, jealousy and murder, all put over with great conviction, and pushed the other Danish filmmakers further in this direction. By 1912, the Danish film companies were multiplying rapidly.

The Swedish film industry was smaller and slower to get started than the Danish industry. Here, Charles Magnusson, a newsreel cameraman for the Svenskabiografteatern cinema chain, started fiction film production for them in 1909, directing a number of the films himself. Production increased in 1912, when the company engaged Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller as directors. They started out by imitating the subjects favoured by the Danish film industry, but by 1913 they were producing their own strikingly original work, which sold very well.

Russia began its film industry in 1908 with Pathé shooting some fiction subjects there, and then the creation of real Russian film companies by Aleksandr Drankov and Aleksandr Khanzhonkov. The Khanzhonkov company quickly became much the largest Russian film company, and remained so until 1918.

In Germany, Oskar Messter had been involved in film-making from 1896, but did not make a significant number of films per year until 1910. When the worldwide film boom started, he, and the few other people in the German film business, continued to sell prints of their own films outright, which put them at a disadvantage. It was only when Paul Davidson, the owner of a chain of cinemas, brought Asta Nielsen and Urban Gad to Germany from Denmark in 1911, and set up a production company, Projektions-AG "Union" (PAGU), for them, that a change-over to renting prints began. Messter replied with a series of longer films starring Henny Porten, but although these did well in the German-speaking world, they were not particularly successful internationally, unlike the Asta Nielsen films. Another of the growing German film producers just before World War I was the German branch of the French Éclair company, Deutsche Éclair. This was expropriated by the German government, and turned into DECLA when the war started. But altogether, German producers only had a minor part of the German market in 1914.

Overall, from about 1910, American films had the largest share of the market in all European countries except France, and even in France, the American films had just pushed the local production out of first place on the eve of World War I. So even if the war had not happened, American films may have become dominant worldwide. Although the war made things much worse for European producers, the technical qualities of American films made them increasingly attractive to audiences everywhere.

Film technique

New film techniques that were introduced in this period include the use of artificial lighting, fire effects and Low-key lighting (i.e. lighting in which most of the frame is dark) for enhanced atmosphere during sinister scenes.

Continuity of action from shot to shot was also refined, such as in Pathé's le Cheval emballé (The Runaway Horse) (1907) where cross-cutting between parallel actions is used. D. W. Griffith also began using cross-cutting in the film The Fatal Hour, made in July 1908. Another development was the use of the Point of View shot, first used in 1910 in Vitagraph's Back to Nature. Insert shots were also used for artistic purposes; the Italian film La mala planta (The Evil Plant), directed by Mario Caserini had an insert shot of a snake slithering over the "Evil Plant".

As films grew longer, specialist writers were employed to simplify more complex stories derived from novels or plays into a form that could be contained on one reel. Genres began to be used as categories; the main division was into comedy and drama, but these categories were further subdivided.

Intertitles containing lines of dialogue began to be used consistently from 1908 onwards, such as in Vitagraph's An Auto Heroine; or, The Race for the Vitagraph Cup and How It Was Won. The dialogue was eventually inserted into the middle of the scene and became commonplace by 1912. The introduction of dialogue titles transformed the nature of film narrative. When dialogue titles came to be always cut into a scene just after a character starts speaking, and then left with a cut to the character just before they finish speaking, then one had something that was effectively the equivalent of a present-day sound film.

During World War I

Industry

The years of the First World War were a complex transitional period for the film industry. The exhibition of films changed from short one-reel programmes to feature films. Exhibition venues became larger and began charging higher prices.

In the United States, these changes brought destruction to many film companies, the Vitagraph company being an exception. Film production began to shift to Los Angeles during World War I. The Universal Film Manufacturing Company was formed in 1912 as an umbrella company. New entrants included the Jesse Lasky Feature Play Company, and Famous Players, both formed in 1913, and later amalgamated into Famous Players-Lasky. The biggest success of these years was David Wark Griffith's The Birth of a Nation (1915). Griffith followed this up with the even bigger Intolerance (1916), but, due to the high quality of film produced in the US, the market for their films was high.

In France, film production shut down due to the general military mobilization of the country at the start of the war. Although film production began again in 1915, it was on a reduced scale, and the biggest companies gradually retired from production. Italian film production held up better, although so called "diva films", starring anguished female leads were a commercial failure. In Denmark, the Nordisk company increased its production so much in 1915 and 1916 that it could not sell all its films, which led to a very sharp decline in Danish production, and the end of Denmark's importance on the world film scene.

The German film industry was seriously weakened by the war. The most important of the new film producers at the time was Joe May, who made a series of thrillers and adventure films through the war years, but Ernst Lubitsch also came into prominence with a series of very successful comedies and dramas.

New techniques

At this time, studios were blacked out to allow shooting to be unaffected by changing sunlight. This was replaced with floodlights and spotlights. The widespread adoption of irising-in and out to begin and end scenes caught on in this period. This is the revelation of a film shot in a circular mask, which gradually gets larger until it expands beyond the frame. Other shaped slits were used, including vertical and diagonal apertures.

A new idea taken over from still photography was "soft focus". This began in 1915, with some shots being intentionally thrown out of focus for expressive effect, as in Mary Pickford starrer Fanchon the Cricket.

It was during this period that camera effects intended to convey the subjective feelings of characters in a film really began to be established. These could now be done as Point of View (POV) shots, as in Sidney Drew's The Story of the Glove (1915), where a wobbly hand-held shot of a door and its keyhole represents the POV of a drunken man. The use of anamorphic (in the general sense of distorted shape) images first appears in these years with Abel Gance directed la Folie du Docteur Tube (The Madness of Dr. Tube). In this film the effect of a drug administered to a group of people was suggested by shooting the scenes reflected in a distorting mirror of the fair-ground type.

Symbolic effects taken over from conventional literary and artistic tradition continued to make some appearances in films during these years. In D. W. Griffith's The Avenging Conscience (1914), the title "The birth of the evil thought" precedes a series of three shots of the protagonist looking at a spider, and ants eating an insect. Symbolist art and literature from the turn of the century also had a more general effect on a small number of films made in Italy and Russia. The supine acceptance of death resulting from passion and forbidden longings was a major feature of this art, and states of delirium dwelt on at length were important as well.

The use of insert shots, i.e. close-ups of objects other than faces, had already been established by the Brighton school, but were infrequently used before 1914. It is really only with Griffith's The Avenging Conscience that a new phase in the use of the Insert Shot starts. As well as the symbolic inserts already mentioned, the film also made extensive use of large numbers of Big Close Up shots of clutching hands and tapping feet as a means of emphasizing those parts of the body as indicators of psychological tension.

Atmospheric inserts were developed in Europe in the late 1910s. This kind of shot is one in a scene which neither contains any of the characters in the story, nor is a Point of View shot seen by one of them. An early example is in Maurice Tourneur directed The Pride of the Clan (1917), in which there is a series of shots of waves beating on a rocky shore to demonstrate the harsh lives of the fishing folk. Maurice Elvey's Nelson; The Story of England's Immortal Naval Hero (1919) has a symbolic sequence dissolving from a picture of Kaiser Wilhelm II to a peacock, and then to a battleship.

By 1914, continuity cinema was the established mode of commercial cinema. One of the advanced continuity techniques involved an accurate and smooth transition from one shot to another. Cutting to different angles within a scene also became well-established as a technique for dissecting a scene into shots in American films. If the direction of the shot changes by more than ninety degrees, it is called a reverse-angle cutting. The leading figure in the full development of reverse-angle cutting was Ralph Ince in his films, such as The Right Girl and His Phantom Sweetheart

The use of flash-back structures continued to develop in this period, with the usual way of entering and leaving a flash-back being through a dissolve. The Vitagraph company's The Man That Might Have Been (William J. Humphrey, 1914), is even more complex, with a series of reveries and flash-backs that contrast the protagonist's real passage through life with what might have been, if his son had not died.

After 1914, cross cutting between parallel actions came to be used – more so in American films than in European ones. Cross-cutting was often used to get new effects of contrast, such as the cross-cut sequence in Cecil B. DeMille's The Whispering Chorus (1918), in which a supposedly dead husband is having a liaison with a Chinese prostitute in an opium den, while simultaneously his unknowing wife is being remarried in church.

Film art

The general trend in the development of cinema, led from the United States, was towards using the newly developed specifically filmic devices for expression of the narrative content of film stories, and combining this with the standard dramatic structures already in use in commercial theatre. D. W. Griffith had the highest standing amongst American directors in the industry, because of the dramatic excitement he conveyed to the audience through his films. Cecil B. DeMille's The Cheat (1915), brought out the moral dilemmas facing their characters in a more subtle way than Griffith. DeMille was also in closer touch with the reality of contemporary American life. Maurice Tourneur was also highly ranked for the pictorial beauties of his films, together with the subtlety of his handling of fantasy, while at the same time he was capable of getting greater naturalism from his actors at appropriate moments, as in A Girl's Folly (1917).

Sidney Drew was the leader in developing "polite comedy", while slapstick was refined by Fatty Arbuckle and Charles Chaplin, who both started with Mack Sennett's Keystone company. They reduced the usual frenetic pace of Sennett's films to give the audience a chance to appreciate the subtlety and finesse of their movement, and the cleverness of their gags. By 1917 Chaplin was also introducing more dramatic plot into his films, and mixing the comedy with sentiment.

In Russia, Yevgeni Bauer put a slow intensity of acting combined with Symbolist overtones onto film in a unique way.

In Sweden, Victor Sjöström made a series of films that combined the realities of people's lives with their surroundings in a striking manner, while Mauritz Stiller developed sophisticated comedy to a new level.

In Germany, Ernst Lubitsch got his inspiration from the stage work of Max Reinhardt, both in bourgeois comedy and in spectacle, and applied this to his films, culminating in his die Puppe (The Doll), die Austernprinzessin (The Oyster Princess) and Madame DuBarry.

Hollywood triumphant

At the start of the First World War, French and Italian cinema had been the most globally popular. The war came as a devastating interruption to European film industries. The American industry, or "Hollywood", as it was becoming known after its new geographical center in California, gained the position it has held, more or less, ever since: film factory for the world and exporting its product to most countries on earth.

By the 1920s, the United States reached what is still its era of greatest-ever output, producing an average of 800 feature films annually,[79] or 82% of the global total (Eyman, 1997). The comedies of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, the swashbuckling adventures of Douglas Fairbanks and the romances of Clara Bow, to cite just a few examples, made these performers' faces well known on every continent. The Western visual norm that would become classical continuity editing was developed and exported – although its adoption was slower in some non-Western countries without strong realist traditions in art and drama, such as Japan.

This development was contemporary with the growth of the studio system and its greatest publicity method, the star system, which characterized American film for decades to come and provided models for other film industries. The studios' efficient, top-down control over all stages of their product enabled a new and ever-growing level of lavish production and technical sophistication. At the same time, the system's commercial regimentation and focus on glamorous escapism discouraged daring and ambition beyond a certain degree, a prime example being the brief but still legendary directing career of the iconoclastic Erich von Stroheim in the late teens and the 1920s.

Sound era

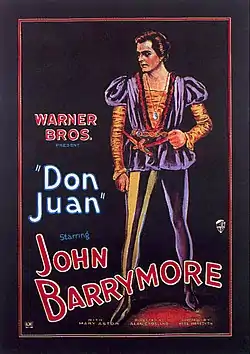

During late 1927, Warners released The Jazz Singer, which was mostly silent but contained what is generally regarded as the first synchronized dialogue (and singing) in a feature film; but this process was actually accomplished first by Charles Taze Russell in 1914 with the lengthy film The Photo-Drama of Creation. This drama consisted of picture slides and moving pictures synchronized with phonograph records of talks and music. The early sound-on-disc processes such as Vitaphone were soon superseded by sound-on-film methods like Fox Movietone, DeForest Phonofilm, and RCA Photophone. The trend convinced the largely reluctant industrialists that "talking pictures", or "talkies", were the future. A lot of attempts were made before the success of The Jazz Singer, that can be seen in the List of film sound systems.

The change was remarkably swift. By the end of 1929, Hollywood was almost all-talkie, with several competing sound systems (soon to be standardized). Total changeover was slightly slower in the rest of the world, principally for economic reasons. Cultural reasons were also a factor in countries like China and Japan, where silents co-existed successfully with sound well into the 1930s, indeed producing what would be some of the most revered classics in those countries, like Wu Yonggang's The Goddess (China, 1934) and Yasujirō Ozu's I Was Born, But... (Japan, 1932). But even in Japan, a figure such as the benshi, the live narrator who was a major part of Japanese silent cinema, found his acting career was ending.

Sound further tightened the grip of major studios in numerous countries: the vast expense of the transition overwhelmed smaller competitors, while the novelty of sound lured vastly larger audiences for those producers that remained. In the case of the U.S., some historians credit sound with saving the Hollywood studio system in the face of the Great Depression (Parkinson, 1995). Thus began what is now often called "The Golden Age of Hollywood", which refers roughly to the period beginning with the introduction of sound until the late 1940s. The American cinema reached its peak of efficiently manufactured glamour and global appeal during this period. The top actors of the era are now thought of as the classic film stars, such as Clark Gable, Katharine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, Greta Garbo, and the greatest box office draw of the 1930s, child performer Shirley Temple.

Creative impact of sound

Creatively, however, the rapid transition was a difficult one, and in some ways, film briefly reverted to the conditions of its earliest days. The late '20s were full of static, stagey talkies as artists in front of and behind the camera struggled with the stringent limitations of the early sound equipment and their own uncertainty as to how to utilize the new medium. Many stage performers, directors and writers were introduced to cinema as producers sought personnel experienced in dialogue-based storytelling. Many major silent filmmakers and actors were unable to adjust and found their careers severely curtailed or even ended.

This awkward period was fairly short-lived. 1929 was a watershed year: William Wellman with Chinatown Nights and The Man I Love, Rouben Mamoulian with Applause, Alfred Hitchcock with Blackmail (Britain's first sound feature), were among the directors to bring greater fluidity to talkies and experiment with the expressive use of sound (Eyman, 1997). In this, they both benefited from, and pushed further, technical advances in microphones and cameras, and capabilities for editing and post-synchronizing sound (rather than recording all sound directly at the time of filming).

.jpg.webp)

Sound films emphasized black history and benefited different genres more so than silents did. Most obviously, the musical film was born; the first classic-style Hollywood musical was The Broadway Melody (1929) and the form would find its first major creator in choreographer/director Busby Berkeley (42nd Street, 1933, Dames, 1934). In France, avant-garde director René Clair made surreal use of song and dance in comedies like Under the Roofs of Paris (1930) and Le Million (1931). Universal Pictures began releasing gothic horror films like Dracula and Frankenstein (both 1931). In 1933, RKO Pictures released Merian C. Cooper's classic "giant monster" film King Kong. The trend thrived best in India, where the influence of the country's traditional song-and-dance drama made the musical the basic form of most sound films (Cook, 1990); virtually unnoticed by the Western world for decades, this Indian popular cinema would nevertheless become the world's most prolific. (See also Bollywood.)

At this time, American gangster films like Little Caesar and Wellman's The Public Enemy (both 1931) became popular. Dialogue now took precedence over "slapstick" in Hollywood comedies: the fast-paced, witty banter of The Front Page (1931) or It Happened One Night (1934), the sexual double entrendres of Mae West (She Done Him Wrong, 1933) or the often subversively anarchic nonsense talk of the Marx Brothers (Duck Soup, 1933). Walt Disney, who had previously been in the short cartoon business, stepped into feature films with the first English-speaking animated feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; released by RKO Pictures in 1937. 1939, a major year for American cinema, brought such films as The Wizard of Oz and Gone with The Wind.

Color in cinema

Previously, it was believed that color films were first projected in 1909 at the Palace Theatre in London (the main problem with the color being that the technique, created by George Smith, (Kinemacolor) only used two colors: green and red, which were mixed additively). But in fact, it was in 1901 when the first color film in history was created. This untitled film was directed by photographer Edward Raymond Turner and his patron Frederick Marshall Lee. The way they did it was to use black and white film rolls, but have green, red, and blue filters go over the camera individually as it shot. To complete the film, they joined the original footage and filters on a special projector. However, both the shooting of the film and its projection suffered from major unrelated issues that, eventually, sank the idea.

Subsequently, in 1916, the technicolor technique arrived (trichromatic procedure (green, red, blue). Its use required a triple photographic impression, incorporation of chromatic filters and cameras of enormous dimensions). The first audiovisual piece that was completely realized with this technique was the short of Walt Disney "Flowers and Trees", directed by Burt Gillett in 1932. Even so, the first film to be performed with this technique will be "The Vanities Fair" (1935) by Rouben Mamoulian. Later on, the technicolor was extended mainly in the musical field as "The Wizard of Oz" or "Singin' in the Rain", in films such as "The Adventures of Robin Hood" or the animation film, "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs".[80]

World War II and its aftermath

The desire for wartime propaganda against the opposition created a renaissance in the film industry in Britain, with realistic war dramas like 49th Parallel (1941), Went the Day Well? (1942), The Way Ahead (1944) and Noël Coward and David Lean's celebrated naval film In Which We Serve in 1942, which won a special Academy Award. These existed alongside more flamboyant films like Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944) and A Matter of Life and Death (1946), as well as Laurence Olivier's 1944 film Henry V, based on the Shakespearean history Henry V. The success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs allowed Disney to make more animated features like Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940), Dumbo (1941) and Bambi (1942).

The onset of US involvement in World War II also brought a proliferation of films as both patriotism and propaganda. American propaganda films included Desperate Journey (1942), Mrs. Miniver (1942), Forever and a Day (1943) and Objective, Burma! (1945). Notable American films from the war years include the anti-Nazi Watch on the Rhine (1943), scripted by Dashiell Hammett; Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Hitchcock's direction of a script by Thornton Wilder; the George M. Cohan biopic, Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), starring James Cagney, and the immensely popular Casablanca, with Humphrey Bogart. Bogart would star in 36 films between 1934 and 1942 including John Huston's The Maltese Falcon (1941), one of the first films now considered a classic film noir. In 1941, RKO Pictures released Citizen Kane made by Orson Welles. It is often considered the greatest film of all time. It would set the stage for the modern motion picture, as it revolutionized film story telling.

The strictures of wartime also brought an interest in more fantastical subjects. These included Britain's Gainsborough melodramas (including The Man in Grey and The Wicked Lady), and films like Here Comes Mr. Jordan, Heaven Can Wait, I Married a Witch and Blithe Spirit. Val Lewton also produced a series of atmospheric and influential small-budget horror films, some of the more famous examples being Cat People, Isle of the Dead and The Body Snatcher. The decade probably also saw the so-called "women's pictures", such as Now, Voyager, Random Harvest and Mildred Pierce at the peak of their popularity.

1946 saw RKO Radio releasing It's a Wonderful Life directed by Italian-born filmmaker Frank Capra. Soldiers returning from the war would provide the inspiration for films like The Best Years of Our Lives, and many of those in the film industry had served in some capacity during the war. Samuel Fuller's experiences in World War II would influence his largely autobiographical films of later decades such as The Big Red One. The Actor's Studio was founded in October 1947 by Elia Kazan, Robert Lewis, and Cheryl Crawford, and the same year Oskar Fischinger filmed Motion Painting No. 1.

In 1943, Ossessione was screened in Italy, marking the beginning of Italian neorealism. Major films of this type during the 1940s included Bicycle Thieves, Rome, Open City, and La Terra Trema. In 1952 Umberto D was released, usually considered the last film of this type.

In the late 1940s, in Britain, Ealing Studios embarked on their series of celebrated comedies, including Whisky Galore!, Passport to Pimlico, Kind Hearts and Coronets and The Man in the White Suit, and Carol Reed directed his influential thrillers Odd Man Out, The Fallen Idol and The Third Man. David Lean was also rapidly becoming a force in world cinema with Brief Encounter and his Dickens adaptations Great Expectations and Oliver Twist, and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger would experience the best of their creative partnership with films like Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes.

1950s

The House Un-American Activities Committee investigated Hollywood in the early 1950s. Protested by the Hollywood Ten before the committee, the hearings resulted in the blacklisting of many actors, writers and directors, including Chayefsky, Charlie Chaplin, and Dalton Trumbo, and many of these fled to Europe, especially the United Kingdom.

The Cold War era zeitgeist translated into a type of near-paranoia manifested in themes such as invading armies of evil aliens, (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The War of the Worlds); and communist fifth columnists, (The Manchurian Candidate).

During the immediate post-war years the cinematic industry was also threatened by television, and the increasing popularity of the medium meant that some film theatres would bankrupt and close. The demise of the "studio system" spurred the self-commentary of films like Sunset Boulevard (1950) and The Bad and the Beautiful (1952).

In 1950, the Lettrists avante-gardists caused riots at the Cannes Film Festival, when Isidore Isou's Treatise on Slime and Eternity was screened. After their criticism of Charlie Chaplin and split with the movement, the Ultra-Lettrists continued to cause disruptions when they showed their new hypergraphical techniques. The most notorious film is Guy Debord's Howls for Sade of 1952.

Distressed by the increasing number of closed theatres, studios and companies would find new and innovative ways to bring audiences back. These included attempts to widen their appeal with new screen formats. Cinemascope, which would remain a 20th Century Fox distinction until 1967, was announced with 1953's The Robe. VistaVision, Cinerama, and Todd-AO boasted a "bigger is better" approach to marketing films to a dwindling US audience. This resulted in the revival of epic films to take advantage of the new big screen formats. Some of the most successful examples of these Biblical and historical spectaculars include The Ten Commandments (1956), The Vikings (1958), Ben-Hur (1959), Spartacus (1960) and El Cid (1961). Also during this period a number of other significant films were produced in Todd-AO, developed by Mike Todd shortly before his death, including Oklahoma! (1955), Around the World in 80 Days (1956), South Pacific (1958) and Cleopatra (1963) plus many more.

Gimmicks also proliferated to lure in audiences. The fad for 3-D film would last for only two years, 1952–1954, and helped sell House of Wax and Creature from the Black Lagoon. Producer William Castle would tout films featuring "Emergo" "Percepto", the first of a series of gimmicks that would remain popular marketing tools for Castle and others throughout the 1960s.

In the U.S., a post-WW2 tendency toward questioning the establishment and societal norms and the early activism of the civil rights movement was reflected in Hollywood films such as Blackboard Jungle (1955), On the Waterfront (1954), Paddy Chayefsky's Marty and Reginald Rose's 12 Angry Men (1957). Disney continued making animated films, notably; Cinderella (1950), Peter Pan (1953), Lady and the Tramp (1955), and Sleeping Beauty (1959). He began, however, getting more involved in live action films, producing classics like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), and Old Yeller (1957). Television began competing seriously with films projected in theatres, but surprisingly it promoted more filmgoing rather than curtailing it.

Limelight is probably a unique film in at least one interesting respect. Its two leads, Charlie Chaplin and Claire Bloom, were in the industry in no less than three different centuries. In the 19th Century, Chaplin made his theatrical debut at the age of eight, in 1897, in a clog dancing troupe, The Eight Lancaster Lads. In the 21st Century, Bloom is still enjoying a full and productive career, having appeared in dozens of films and television series produced up to and including 2013. She received particular acclaim for her role in The King's Speech (2010).

Golden age of Asian cinema

Following the end of World War II in the 1940s, the following decade, the 1950s, marked a 'golden age' for non-English world cinema,[81][82] especially for Asian cinema.[83][84] Many of the most critically acclaimed Asian films of all time were produced during this decade, including Yasujirō Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953), Satyajit Ray's The Apu Trilogy (1955–1959) and Jalsaghar (1958), Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (1954) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954), Raj Kapoor's Awaara (1951), Mikio Naruse's Floating Clouds (1955), Guru Dutt's Pyaasa (1957) and Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), and the Akira Kurosawa films Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai (1954) and Throne of Blood (1957).[83][84]

During Japanese cinema's 'Golden Age' of the 1950s, successful films included Rashomon (1950), Seven Samurai (1954) and The Hidden Fortress (1958) by Akira Kurosawa, as well as Yasujirō Ozu's Tokyo Story (1953) and Ishirō Honda's Godzilla (1954).[85] These films have had a profound influence on world cinema. In particular, Kurosawa's Seven Samurai has been remade several times as Western films, such as The Magnificent Seven (1960) and Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), and has also inspired several Bollywood films, such as Sholay (1975) and China Gate (1998). Rashomon was also remade as The Outrage (1964), and inspired films with "Rashomon effect" storytelling methods, such as Andha Naal (1954), The Usual Suspects (1995) and Hero (2002). The Hidden Fortress was also the inspiration behind George Lucas' Star Wars (1977). Other famous Japanese filmmakers from this period include Kenji Mizoguchi, Mikio Naruse, Hiroshi Inagaki and Nagisa Oshima.[83] Japanese cinema later became one of the main inspirations behind the New Hollywood movement of the 1960s to 1980s.

During Indian cinema's 'Golden Age' of the 1950s, it was producing 200 films annually, while Indian independent films gained greater recognition through international film festivals. One of the most famous was The Apu Trilogy (1955–1959) from critically acclaimed Bengali film director Satyajit Ray, whose films had a profound influence on world cinema, with directors such as Akira Kurosawa,[86] Martin Scorsese,[87][88] James Ivory,[89] Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Kazan, François Truffaut,[90] Steven Spielberg,[91][92][93] Carlos Saura,[94] Jean-Luc Godard,[95] Isao Takahata,[96] Gregory Nava, Ira Sachs, Wes Anderson[97] and Danny Boyle[98] being influenced by his cinematic style. According to Michael Sragow of The Atlantic Monthly, the "youthful coming-of-age dramas that have flooded art houses since the mid-fifties owe a tremendous debt to the Apu trilogy".[99] Subrata Mitra's cinematographic technique of bounce lighting also originates from The Apu Trilogy.[100] Other famous Indian filmmakers from this period include Guru Dutt,[83] Ritwik Ghatak,[84] Mrinal Sen, Raj Kapoor, Bimal Roy, K. Asif and Mehboob Khan.[101]

The cinema of South Korea also experienced a 'Golden Age' in the 1950s, beginning with director Lee Kyu-hwan's tremendously successful remake of Chunhyang-jon (1955).[102] That year also saw the release of Yangsan Province by the renowned director, Kim Ki-young, marking the beginning of his productive career. Both the quality and quantity of filmmaking had increased rapidly by the end of the 1950s. South Korean films, such as Lee Byeong-il's 1956 comedy Sijibganeun nal (The Wedding Day), had begun winning international awards. In contrast to the beginning of the 1950s, when only 5 films were made per year, 111 films were produced in South Korea in 1959.[103]

The 1950s was also a 'Golden Age' for Philippine cinema, with the emergence of more artistic and mature films, and significant improvement in cinematic techniques among filmmakers. The studio system produced frenetic activity in the local film industry as many films were made annually and several local talents started to earn recognition abroad. The premiere Philippine directors of the era included Gerardo de Leon, Gregorio Fernández, Eddie Romero, Lamberto Avellana, and Cirio Santiago.[104][105]

1960s

During the 1960s, the studio system in Hollywood declined, because many films were now being made on location in other countries, or using studio facilities abroad, such as Pinewood in the UK and Cinecittà in Rome. "Hollywood" films were still largely aimed at family audiences, and it was often the more old-fashioned films that produced the studios' biggest successes. Productions like Mary Poppins (1964), My Fair Lady (1964) and The Sound of Music (1965) were among the biggest money-makers of the decade. The growth in independent producers and production companies, and the increase in the power of individual actors also contributed to the decline of traditional Hollywood studio production.

There was also an increasing awareness of foreign language cinema in America during this period. During the late 1950s and 1960s, the French New Wave directors such as François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard produced films such as Les quatre cents coups, Breathless and Jules et Jim which broke the rules of Hollywood cinema's narrative structure. As well, audiences were becoming aware of Italian films like Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita and the stark dramas of Sweden's Ingmar Bergman.

In Britain, the "Free Cinema" of Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson and others lead to a group of realistic and innovative dramas including Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, A Kind of Loving and This Sporting Life. Other British films such as Repulsion, Darling, Alfie, Blowup and Georgy Girl (all in 1965–1966) helped to reduce prohibitions of sex and nudity on screen, while the casual sex and violence of the James Bond films, beginning with Dr. No in 1962 would render the series popular worldwide.

During the 1960s, Ousmane Sembène produced several French- and Wolof-language films and became the "father" of African Cinema. In Latin America, the dominance of the "Hollywood" model was challenged by many film makers. Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino called for a politically engaged Third Cinema in contrast to Hollywood and the European auteur cinema.

Further, the nuclear paranoia of the age, and the threat of an apocalyptic nuclear exchange (like the 1962 close-call with the USSR during the Cuban Missile Crisis) prompted a reaction within the film community as well. Films like Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove and Fail Safe with Henry Fonda were produced in a Hollywood that was once known for its overt patriotism and wartime propaganda.

In documentary film the sixties saw the blossoming of Direct Cinema, an observational style of film making as well as the advent of more overtly partisan films like In the Year of the Pig about the Vietnam War by Emile de Antonio. By the late 1960s however, Hollywood filmmakers were beginning to create more innovative and groundbreaking films that reflected the social revolution taken over much of the western world such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Rosemary's Baby (1968), Midnight Cowboy (1969), Easy Rider (1969) and The Wild Bunch (1969). Bonnie and Clyde is often considered the beginning of the so-called New Hollywood.

In Japanese cinema, Academy Award-winning director Akira Kurosawa produced Yojimbo (1961), which like his previous films also had a profound influence around the world. The influence of this film is most apparent in Sergio Leone's A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and Walter Hill's Last Man Standing (1996). Yojimbo was also the origin of the "Man with No Name" trend.

1970s

The New Hollywood was the period following the decline of the studio system during the 1950s and 1960s and the end of the production code, (which was replaced in 1968 by the MPAA film rating system). During the 1970s, filmmakers increasingly depicted explicit sexual content and showed gunfight and battle scenes that included graphic images of bloody deaths – a good example of this is Wes Craven's The Last House on the Left (1972).

Post-classical cinema is the changing methods of storytelling of the New Hollywood producers. The new methods of drama and characterization played upon audience expectations acquired during the classical/Golden Age period: story chronology may be scrambled, storylines may feature unsettling "twist endings", main characters may behave in a morally ambiguous fashion, and the lines between the antagonist and protagonist may be blurred. The beginnings of post-classical storytelling may be seen in 1940s and 1950s film noir films, in films such as Rebel Without a Cause (1955), and in Hitchcock's Psycho. 1971 marked the release of controversial films like Straw Dogs, A Clockwork Orange, The French Connection and Dirty Harry. This sparked heated controversy over the perceived escalation of violence in cinema.

During the 1970s, a new group of American filmmakers emerged, such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Woody Allen, Terrence Malick, and Robert Altman. This coincided with the increasing popularity of the auteur theory in film literature and the media, which posited that a film director's films express their personal vision and creative insights. The development of the auteur style of filmmaking helped to give these directors far greater control over their projects than would have been possible in earlier eras. This led to some great critical and commercial successes, like Scorsese's Taxi Driver, Coppola's The Godfather films, William Friedkin's The Exorcist, Altman's Nashville, Allen's Annie Hall and Manhattan, Malick's Badlands and Days of Heaven, and Polish immigrant Roman Polanski's Chinatown. It also, however, resulted in some failures, including Peter Bogdanovich's At Long Last Love and Michael Cimino's hugely expensive Western epic Heaven's Gate, which helped to bring about the demise of its backer, United Artists.

The financial disaster of Heaven's Gate marked the end of the visionary "auteur" directors of the "New Hollywood", who had unrestrained creative and financial freedom to develop films. The phenomenal success in the 1970s of Spielberg's Jaws originated the concept of the modern "blockbuster". However, the enormous success of George Lucas' 1977 film Star Wars led to much more than just the popularization of blockbuster film-making. The film's revolutionary use of special effects, sound editing and music had led it to become widely regarded as one of the single most important films in the medium's history, as well as the most influential film of the 1970s. Hollywood studios increasingly focused on producing a smaller number of very large budget films with massive marketing and promotional campaigns. This trend had already been foreshadowed by the commercial success of disaster films such as The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno.

During the mid-1970s, more pornographic theatres, euphemistically called "adult cinemas", were established, and the legal production of hardcore pornographic films began. Porn films such as Deep Throat and its star Linda Lovelace became something of a popular culture phenomenon and resulted in a spate of similar sex films. The porn cinemas finally died out during the 1980s, when the popularization of the home VCR and pornography videotapes allowed audiences to watch sex films at home. In the early 1970s, English-language audiences became more aware of the new West German cinema, with Werner Herzog, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Wim Wenders among its leading exponents.

In world cinema, the 1970s saw a dramatic increase in the popularity of martial arts films, largely due to its reinvention by Bruce Lee, who departed from the artistic style of traditional Chinese martial arts films and added a much greater sense of realism to them with his Jeet Kune Do style. This began with The Big Boss (1971), which was a major success across Asia. However, he didn't gain fame in the Western world until shortly after his death in 1973, when Enter the Dragon was released. The film went on to become the most successful martial arts film in cinematic history, popularized the martial arts film genre across the world, and cemented Bruce Lee's status as a cultural icon. Hong Kong action cinema, however, was in decline due to a wave of "Bruceploitation" films. This trend eventually came to an end in 1978 with the martial arts comedy films, Snake in the Eagle's Shadow and Drunken Master, directed by Yuen Woo-ping and starring Jackie Chan, laying the foundations for the rise of Hong Kong action cinema in the 1980s.

While the musical film genre had declined in Hollywood by this time, musical films were quickly gaining popularity in the cinema of India, where the term "Bollywood" was coined for the growing Hindi film industry in Bombay (now Mumbai) that ended up dominating South Asian cinema, overtaking the more critically acclaimed Bengali film industry in popularity. Hindi filmmakers combined the Hollywood musical formula with the conventions of ancient Indian theatre to create a new film genre called "Masala", which dominated Indian cinema throughout the late 20th century.[106] These "Masala" films portrayed action, comedy, drama, romance and melodrama all at once, with "filmi" song and dance routines thrown in. This trend began with films directed by Manmohan Desai and starring Amitabh Bachchan, who remains one of the most popular film stars in South Asia. The most popular Indian film of all time was Sholay (1975), a "Masala" film inspired by a real-life dacoit as well as Kurosawa's Seven Samurai and the Spaghetti Westerns.

The end of the decade saw the first major international marketing of Australian cinema, as Peter Weir's films Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Last Wave and Fred Schepisi's The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith gained critical acclaim. In 1979, Australian filmmaker George Miller also garnered international attention for his violent, low-budget action film Mad Max.

1980s

During the 1980s, audiences began increasingly watching films on their home VCRs. In the early part of that decade, the film studios tried legal action to ban home ownership of VCRs as a violation of copyright, which proved unsuccessful. Eventually, the sale and rental of films on home video became a significant "second venue" for exhibition of films, and an additional source of revenue for the film industries. Direct-to-video (niche) markets usually offered lower quality, cheap productions that were not deemed very suitable for the general audiences of television and theatrical releases.