History of swimwear

History of swimwear traces the changes in the styles of men's and women's swimwear over time and between cultures, and touches on the social, religious and legal attitudes to swimming and swimwear.

In classical antiquity and in most cultures, swimming was either in the nude or the swimmer would merely strip to their underwear. In the Renaissance, swimming was strongly discouraged, and into the 18th century swimming was regarded as of doubtful morality, and had to be justified on health grounds. In the Victorian era swimwear was of a style of outer clothing of the time, which were cumbersome and even dangerous in the water, especially in the case of dress-style swimwear for women. Since the early 20th century, swimming came to be regarded as a legitimate leisure activity or pastime and clothing made specifically for swimming became the norm. Since then, swimwear for women has become increasingly more scanty and form-fitting, and the use of high-tech materials has become more common.

Classical ages

In classical antiquity swimming and bathing were done naked. There are Roman murals which show women playing sports and exercising wearing two-piece suits covering the areas around their breasts and hips in a fashion remarkably similar to the present-day bikini. However, there is no evidence that they were used for swimming. All classical pictures of swimming show nude swimmers.

In various cultural traditions one swims, if not in the nude, in a version in suitable material of a garment or undergarment commonly worn on land, e.g. a loincloth such as the Japanese man's fundoshi.

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages saw a resurgence in bathing, both in indoor bathhouses and open air, and was largely still without clothing. Contemporary illustrations depict men and women bathing together, either nude, or with cloth wrapped around the groin. The end of the era saw more restrictions placed on bathing attire; a 1548 German law required bathers to wear drawers or cloth around the waist or pay a fine.[1]

In the Renaissance, swimming and outdoor bathing were discouraged in the Christian West and there was little need for swimwear.

17th century

Female bathing costumes were derived from those worn at Bath and other spas. It would appear that until the 1670s nude female bathing in the spas was the norm and that after that time women bathed clothed. Celia Fiennes gave a detailed description of the standard ladies' bathing costume in 1687:

The Ladyes go into the bath with Garments made of a fine yellow canvas, which is stiff and made large with great sleeves like a parson’s gown; the water fills it up so that it is borne off that your shape is not seen, it does not cling close as other linning, which Lookes sadly in the poorer sort that go in their own linning. The Gentlemen have drawers and wastcoates of the same sort of canvas, this is the best linning, for the bath water will Change any other yellow.[2]

18th century

The bathing gown in the 18th century was a loose ankle-length full-sleeve chemise-type gown made of wool or flannel, so that modesty or decency was not threatened.[3]

In the United Kingdom until the mid-19th century there was no law against nude swimming, and each town was free to make its own laws. For example, the Bath Corporation official bathing dress code of 1737 prescribed, for men:

It is Ordered Established and Decreed by this Corporation that no Male person above the age of ten years shall at any time hereafter go into any Bath or Baths within this City by day or by night without a Pair of Drawers and a Waistcoat on their bodies.[2]:50

In rivers, lakes, streams and the sea men swam in the nude, where the practice was common. Those who did not swim in the nude, stripped to their underwear.

The Bath Corporation official bathing dress code of 1737 prescribed, for women:

No Female person shall at any time hereafter go into a Bath or Baths within this City by day or by night without a decent Shift on their bodies.[2]

The Expedition of Humphry Clinker was published in 1771 and its description of ladies’ bathing costume is different from that of Celia Fiennes a hundred years earlier:

The ladies wear jackets and petticoats of brown linen, with chip hats, in which they fix their handkerchiefs to wipe the sweat from their faces; but, truly, whether it is owing to the steam that surrounds them, or the heat of the water, or the nature of the dress, or to all these causes together, they look so flushed, and so frightful, that I always turn my eyes another way.[4]

19th century

The English practice of men swimming in the nude was banned in the United Kingdom in 1860. Drawers, or caleçons as they were called, came into use in the 1860s. Even then there were many who protested against them and wanted to remain in the nude. Francis Kilvert described men's bathing suits coming into use in the 1870s as "a pair of very short red and white striped drawers".[5]

In the first half of the 19th century the top became knee-length while an ankle-length drawer was added as a bottom. By the second half of the 19th century, in France, the sleeves started to vanish, the bottom became shorter to reach only the knees and the top became hip-length and both became more form fitting.[3][6] In the 1900s women wore wool dresses on the beach that were made of up to 9 yards (8.2 m) of fabric.[7]

Penelope Byrde points out that Smollett's description may not be accurate, for he describes a two-piece costume, not the one piece shift or smock that most people describe and is depicted in contemporary prints. His description does, however, tally with Elizabeth Grant's description of the guide's costume at Ramsgate in 1811. The only difference is in the fabric the costumes are made of. Flannel, however, was a common fabric for sea bathing costumes as many believed the warmer fabric was necessary in cold water.[8]

In the West, in the 19th century women wore a bathing gown in the water. These were loose ankle-length full-sleeve chemise-type gown made of wool or flannel, so that modesty or decency was not threatened.[3] They were long dresses of fabrics that would not become transparent when wet, with weights sewn into the hems so that they would not rise up in the water. The men's swim suit, a rather form-fitting wool garment with long sleeves and legs similar to long underwear, was developed and would change little for a century.

In the 19th century, the woman's double suit was common, comprising a gown from shoulder to knees plus a set of trousers with leggings going down to the ankles. In the first half of the 19th century the top became knee-length while an ankle-length drawer was added as a bottom. By the second half of the 19th century, in France, the sleeves started to vanish, the bottom became shorter to reach only the knees and the top became hip-length and both became more form fitting.[3][6] In the 1900s women wore wool dresses on the beach that were made of up to 9 yards (8.2 m) of fabric.[7]

In the Victorian era, Western cultures deplored nudity of any degree, and people took great pains to cover themselves, even bare chested male swimmers at ocean beaches. Popular beach resorts were commonly equipped with bathing machines designed to avoid the exposure of people in swimsuits, especially to people of the opposite sex.

In the United States, beauty pageants of women in bathing costumes became popular from the 1880s. However, such events were not regarded as respectable. Beauty contests became more respectable with the first modern "Miss America" contest held in 1921, though less respectable beauty contests continued to be held.

Cartoon by George du Maurier in Punch, 1877, showing men's and children's bathing suits

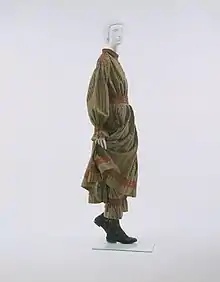

Cartoon by George du Maurier in Punch, 1877, showing men's and children's bathing suits American bathing suit, 1876-1880

American bathing suit, 1876-1880 American bathing suit, 1885

American bathing suit, 1885 American bathing suit, 1890–1895

American bathing suit, 1890–1895

Early 20th century

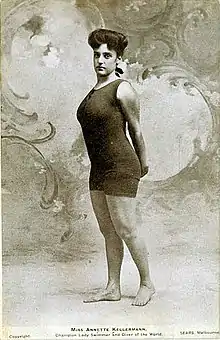

In 1907, the swimmer Annette Kellerman from Australia visited the United States as an "underwater ballerina", a version of synchronised swimming involving diving into glass tanks. She was arrested on a Boston beach for indecent exposure because her swimsuit showed arms, legs and the neck, a costume she adopted from England,[3] and which was similar to men's swimsuits of the time. Kellerman changed the suit to have long arms and legs and a collar, still keeping the close fit that revealed the shapes underneath. Kellerman marketed a line of bathing suits and her style of one-piece suits came to be known as "the Annette Kellerman". The one-piece swimming tights became accepted swimsuit attire for women in parts of Europe by 1910.[9] Harper's Bazaar praised the Kellerman swimsuit, writing in June 1920 (vol. 55, no. 6, p. 138) "Annette Kellerman Bathing Attire is distinguished by an incomparable, daring beauty of fit that always remains refined." The following year, in June 1921 (vol. 54, no. 2504, p. 101) it wrote that these bathing suits were "famous ... for their perfect fit and exquisite, plastic beauty of line."[3]

1910s

Despite opposition from some groups, the form-fitting style proved popular. It was not long before swimwear started to shrink further. At first arms were exposed and then legs up to mid-thigh. Necklines receded from around the neck down to around the top of the bosom. The development of new fabrics allowed for new varieties of more comfortable and practical swimwear.

Female swimming was introduced at the 1912 Summer Olympics. Competitors from 17 countries took part, with women from nine countries wearing swimsuits similar to Kellerman's swimsuit, which were similar to swimsuits worn by the male swimmers. In 1913, inspired by the breakthrough, the designer Carl Jantzen made the first functional two-piece swimwear, a close-fitting one-piece with shorts on the bottom and short sleeves on top.[10] Silent films such as The Water Nymph (1912) saw Mabel Normand in revealing attire, and this was followed by the daringly dressed Sennett Bathing Beauties (1915–1929). The name "swim suit" was coined in 1915 by Jantzen Knitting Mills, a sweater manufacturer who launched a swimwear brand named the Red Diving Girl.[11] The first annual bathing-suit day at New York's Madison Square Garden in 1916 was a landmark.[12] The swimsuit apron, a design for early swimwear, disappeared by 1918, leaving a tunic covering the shorts.[13]

Public nudity was a major concern in designing early swimwear. It was a major factor behind the non-participation of American women in the 1912 Olympics.[14] At those Games, British women wore full-body silk suits of such a volume that they could be passed through a wedding ring. The suits were complemented by bras and bikini-style briefs as they became transparent when wet. Women's coaches were rare at early Olympics, and to further reduce the chances of harassment women were accompanied by chaperones.[15] Even men wore one-piece swimsuits covering the body from hips to shoulders up to the 1940s.[16]

1920s

During the 1920s and 1930s, people began to shift from "taking in the water" to "taking in the sun", at bathhouses and spas, and swimsuit designs shifted from functional considerations to incorporate more decorative features. Rayon was used in the 1920s in the manufacture of tight-fitting swimsuits,[7] but its durability, especially when wet, proved problematic,[17] with jersey and silk also sometimes being used.[18][19]

Burlesque and vaudeville performers wore two-piece outfits in the 1920s. The 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera shows Russian women wearing early two-piece swimsuits which expose their midriff, and a few who are topless. Films of holidaymakers in Germany in the 1930s show women wearing two-piece suits,[20] In 1928, Speedo introduced their racerback silk suit that was optimized to fit the body shape.[21][22]

1930s

By the 1930s men began to go without shirts for swimming,[23] and barechestedness in male swimwear became the norm by the end of the 1940s, including in competitive swimming events, in which men are not only barechested, but wear a swimming suit that is intended merely to meet public decency requirements. The norm of male barechestedness in swimwear extended to other competitive sports, such as professional boxing and professional wrestling.

By the 1930s, necklines plunged at the back, sleeves disappeared and sides were cut away and tightened. With the development of new clothing materials, particularly latex and nylon, through the 1930s swimsuits gradually began hugging the body, with shoulder straps that could be lowered for tanning.[13] Hollywood endorsed the new glamour with films such as Neptune's Daughter (1949) in which Esther Williams wore provocatively named costumes such as "Double Entendre" and "Honey Child".[24] Williams, who also was an Amateur Athletic Union champion in the 100 meter freestyle (1939)[25][26] also portrayed Kellerman in the 1952 film Million Dollar Mermaid (titled as The One Piece Bathing Suit in UK).[27] American designer Adele Simpson, a Coty American Fashion Critics' Awards winner (1947) and a notable alumna of the New York art school Pratt Institute, who believed clothes must be comfortable and practical designed a large part of her wardrobe which included mostly one-piece suits that were considered fashionable even in the early 1980s.[28] This was when Cole of California started marketing revealing prohibition suits and Catalina Swimwear introduced almost bare-back designs.[29]

Coco Chanel made suntans fashionable,[24] and in 1932 French designer Madeleine Vionnet offered an exposed midriff in an evening gown. They were seen a year later in Gold Diggers of 1933. The Busby Berkeley film Footlight Parade of 1932 showcases aquachoreography that featured bikinis. Dorothy Lamour's The Hurricane (1937) also showed two-piece bathing suits.[20] The 1934 film, Fashions of 1934 featured chorus girls wearing two-piece outfits which look identical to modern bikinis.[30] In 1934, a National Recreation Association study on the use of leisure time found that swimming, encouraged by the freedom of movement the new swimwear designs provided, was second only to movies in popularity as free time activity out of a list of 94 activities.[3] In 1935 American designer Claire McCardell cut out the side panels of a maillot-style bathing suit, the bikini's forerunner.[31] The 1938 invention of the Telescopic Watersuit in shirred elastic cotton ushered into the end the era of wool. Cotton sun-tops, printed with palm trees, and silk or rayon pyjamas, usually with a blouse top, became popular by 1939.[24]

Speedo racerback silk suit that uncovered the shoulder blades almost resulted in disqualification of Clare Dennis at the 1932 Olympics,[32] but became a norm by 1936.[33] Meanwhile, men were allowed to swim in bare-chest suits in 1936, and in briefs only at the 1948 Olympics.[21][34]

1940s

Wartime production during World War II required vast amounts of cotton, silk, nylon, wool, leather, and rubber. In 1942, the United States War Production Board issued Regulation L-85, cutting the use of natural fibers in clothing[35] and mandating a 10% reduction in the amount of fabric in women's beachwear.[36] To comply with the regulations, swimsuit manufacturers produced two-piece suits with bare midriffs.[37] The fabric shortage continued for some time after the end of the war.

Women's swimwear of the 1930s and 1940s incorporated increasing degrees of midriff exposure. Teen magazines of late 1940s and 1950s featured similar designs of midriff-baring suits and tops. However, midriff fashion was stated as only for beaches and informal events and considered indecent to be worn in public.[38]

Because of the figure-hugging nature of these garments, glamour photography since the 1940s and 1950s has often featured people wearing swimsuits. This type of glamour photography eventually evolved into swimsuit photography exemplified by the annual Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue. Beauty contests also required contestants to wear form-fitting swimsuits.

Two-piece swimsuits without the usual skirt panel and other superfluous material started appearing in the U.S. when the government ordered the 10% reduction in fabric used in woman's swimwear in 1943 as wartime rationing.[36] By that time, two-piece swimsuits were ubiquitous on American beaches. The July 9, 1945, Life shows women in Paris wearing similar items. Hollywood stars like Ava Gardner, Rita Hayworth and Lana Turner tried similar swimwear or beachwear.[39] Pin ups of Hayworth and Esther Williams in the costume were widely distributed.[10] The most provocative swimsuit was the 1946 Moonlight Buoy, a bottom and a top of material that weighed only eight ounces. What made the Moonlight Buoy distinctive was a large cork buckle attached to the bottoms, which made it possible to tie the top to the cork buckle and splash around au naturel while keeping both parts of the suit afloat. Life magazine had a photo essay on the Moonlight Buoy and wrote, "The name of the suit, of course, suggests the nocturnal conditions under which nude swimming is most agreeable."[40]

1950s

Swimwear of the 1940s, 50s and early 60s followed the silhouette mostly from the early 1930s whereas after World War II, a new wardrobe and style of vacation-swimwear arose, coupled with an increase of leisure time and bustling postwar resorts.[41] In 1951, a huge celebration called "The Festival of Britain" was promoted of everything new and modern and cast a line into the future, building on a feeling of hope.[42] Beachwear style were very popular in U.S and Europe,[41] but this fashion originated on the French Riviera, which people was quoted this place as "A sunny place for shady people".[42] Keeping in line with the ultra-feminine look dominated by Dior which brought out his one and only collection of swimwear for the Cole of California in 1955.[42] He designed a series of floral printed swimsuits with halter neckline style. It evolved into a dress followed his New Look silhouette with cinched waists and constructed bustlines, accessorized with earrings, bracelets, hats, scarves, sunglasses, hand bags and cover-ups.[43] American Women inspired by Hollywood's film stars For example, Doris Day offering a” girl-next-door’ look and the accession and coronation of the young Queen Elizabeth in February 1952 and June 1953 respectively.[44]

For the early 50s, despite the reaction to the two-piece swimsuit worn by Brigitte Bardot in Manina, the Girl in the Bikini in 1952, most women in the 1950s still wore one-piece suits.[41] To increasing female emancipation and realized the commercial possibilities of beauty pageants, big companies launched beauty contests to find girls who could help promote products, believing that a picture of a pretty girl in a swimsuit was the best promotion. Instead of swimsuits, these contests popularized the playsuit, but swimsuits remained the highlight in the beauty contest.[42]

The first bikinis appeared just after World War II. Early examples were not very different from the women's two pieces common since the 1920s, except that they had a gap below the breast line allowing for a section of bare midriff. They were named after Bikini Atoll, the site of several nuclear weapons tests, for their supposed explosive effect on the viewer. Beside Christian Dior, some designers also launched the swimwear collection, such as Bob and Bill Meistrell of body glove and Robert and Jack O’Neill of the surf brand O’Neill.[42] Many of these pre-bikinis had fancy names like Double Entendre, Honey Child (to maximize small bosoms), Shipshape (to minimize large bosoms), Diamond Lil (trimmed with rhinestones and lace), Swimming In Mink (trimmed with fur across the bodice) and Spearfisherman (heavy poplin with a rope belt for carrying a knife), Beau Catcher, Leading Lady, Pretty Foxy, Side Issue, Forecast, and Fabulous Fit.[40] However, the bikini was banned from the Miss World contest, following the crowning of Miss Sweden. Some people declared the bikini to be morally ‘indecent’. Even in Europe in 1950, there was an Italian magazine also declared that the Bikini should be worn purely for the sunbathing purposes or on board boats.[42]

According to Vogue the swimwear had become more of "state of dress, not undress" by the mid-1950s.[43] Bikini had a colorful period on the cinema screens and made an impact in the late 50s, inspired by the film such as And God Created Woman by Roger Vadim, launched Bardot into the spotlight and became the benchmark for bikini on celluloid. Also, her outfit sets a whole new trend for sex symbols.[42]

Starting in the 1940s, the manufacturing advances enabled swimsuits to fit without the help of elastic, and aid as performance aid in competitive swimming.[42] In the early 1950s, other synthetics beside the screen print technique was being developed, such as polyester and acrylic, with quick-drying properties. In U.S, the Hawaiian -Japanese- inspired prints were often used. In Europe, Emilio Pucci moved swimwear textile on a generation when he began to design prints for Rose Marrie Reid swimwear.[41] By the late 1950s, new materials were developed and applied on the corsetry swimwear, such as Lastex, a fabric woven from artificial chromspun acetate that used for a more tightly fitted appearance.

Speedo produced the wool and cotton swimwear for the Melbourne Olympics in 1956.[42] In 1956, Speedo became the first company to introduce nylon.[45]

Men's swimsuits developed roughly in parallel to women's during this period, with the shorts covering progressively less. Racing-style "speedo" suits became popular, as did thongs, G-strings and bikini style briefs. Typically these are more popular in more tropical regions; however, they may also be worn at public swimming pools and inland lakes.

1960s

In 1964 designer Rudi Gernreich conceived and produced the monokini,[46] a revolutionary and controversial design included a bottom that "extended from the midriff to the upper thigh"[47] and was "held up by shoestring laces that make a halter around the neck."[48][46]

1970s

In the 1970s Speedo added elastane to their swimsuits that improved their elasticity, durability and reduced water drag – 21 out of 22 records at the 1972 Olympics were broken using nylon/elastane suits.[21]

At the same Olympics, East German swimmers adopted suits that were tightly following the body shape, the so-called "skinsuits". They were initially made of cotton and became virtually transparent when wet. The revealing shape and transparency caused outrage among US swimmers; meanwhile, at the 1973 World Aquatics Championships, East German women won 10 of 14 events and set seven world records. Those championships became the turning point for the world to adopt the skinsuit, modified with novel synthetic materials, as a standard competitive swimwear.[49]

During the same era, East Germany became noteworthy for its nude beaches, an unusual freedom allowed in the regimented communist bloc.[50]

1980s

In 1985, Gernreich unveiled the lesser known pubikini, a bathing suit meant to expose pubic hair.[51] The pubikini is a small piece of fabric that hugs the hips and buttocks but leaves the pubic region exposed,[52] described as a tiny V-shaped fabric strip and a piece de resistance totally freeing the human body.[53] It featured a thong-style bottom[54] while the front was a tiny V-shaped strip of fabric that dipped below the woman's mons pubis, exposing her pubic hair and portions of her vulva.[52][55] This was his last design, four weeks before his death.[56][57]

1990s

Tankini and the concept of mix-and-match swimwears were the two major innovations in that genre in the late 1990s.[58] Designer Anne Cole, the US swimwear mogul, was the originator of this style.[59] Hailed as the first major innovation in women's swimsuit design in several decades, the two-piece tankini blended the freedom of a bikini with the more modest coverage of a one-piece bathing suit, and quickly captured nearly a third of the swimwear market.[60][61] Aimed at closing a gap in the swimwear market, the popularity of tankini largely came from Cole's tapping into women's anxieties about swimwear.[62] In the years following its introduction tankinis diversified in style and range, adding other big name designers such as Ralph Lauren, Donna Karan, Nautica, and Calvin Klein.[63]

For men, longer and baggier shorts became popular in this era, with the hems often reaching to the knees. Often called boardshorts and swim trunks, these were worn lower on the hips than regular shorts.

2000s

In 2005, a controversy broke out when Buddhists complained against swimwear manufacturer Ondade Mar and lingerie giant Victoria's Secret started marketing tankinis featuring Buddhist iconography.[64] In the same year Nike's breast cancer awareness swimwear collection featured four different cuts of tankini.[65]

In 2000, Speedo launched the Fastskin suit series that mimicked shark skin. Their surface contained bumps and ridges that channeled the water over the swimmer's body approximately 3% more efficiently than traditional materials.[66][67] Those suits covered most of the body, from neck to ankles and wrists, and their shape was optimized for specific swimming strokes, compressing some body parts while allowing more freedom to the others.[68][69] Those suits were approved for the 2000 Olympics, where they helped win 83% of the medals.[66] By the next Olympics, similar suits had been developed by Tyr Sport, Inc., but they were not approved by the FINA.[70]

In July 2009, FINA voted to ban non-textile (non-woven) swimsuits in competitive events from 2010. The new policy was implemented to combat the issues associated with performance enhancing costumes, hindering the ability to accurately measure the performance of swimmers. Subsequently, the new ruling states that men's swimsuits may maximally cover the area from the navel to the knee, and women's counterparts from the shoulder to the knee.[71][72]

References

Citations

- Des Grafen Wolrad von Waldeck Tagebuch während des Reichstags zu Zusburg, 1548

- Byrde, Penelope (1987). "That Frightful Unbecoming Dress: Clothes for Spa Bathing at Bath". Costume. 21 (1): 48–49. doi:10.1179/cos.1987.21.1.44. ISSN 0590-8876.

- Claudia B. Kidwell, Women's Bathing and Swimming Costume in the United States, Smithsonian Institution Press, City of Washington, 1968

- Smollett, Tobias George (1906). The Expedition of Humphry Clinker. New York: The Century Company. pp. 38–39.

- Cinder, Cec (1998). The Nudist Idea. Ultraviolet Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-9652085-0-5.

- Herbert Sanchez, A Brief History Of Bathing Suits, Article Garden

- Sydelle, John. "The Swimsuit Industry". Chron. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "Bathing - Jane Austen at the seaside". jasa.net.au. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

- Liz Conor, The spectacular modern woman: feminine visibility in the 1920s, page 152, Indiana University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-253-34391-7

- Hoover, Elizabeth D. (5 July 2006). "60 Years of Bikinis". American Heritage Inc. Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- The Beginning History of Swimwear Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, Global Intimate Wear, 08-07-2012

- Jean Preer, "The Postmaster General and "The Magazine for Men"Prologue Magazine, page 1, Spring 1990, Vol. 23, No. 1, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

- "History of the Bikini". Carnival.

- Shelton, Sandi Kahn (4 August 2012) Women swimmers bucked tide of sexism to compete in Olympics 100 years ago; SCSU librarian's book says competition deemed 'too unfemale' (video). nhregister.com

- Manning, Jo (11 August 2008) First champ 'would be thrilled'. BBC

- Daily News, pp. 1, 5

- Kadolph, Sara J.; Langford, Anna L. (2001). Textiles (9 ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-025443-6.

- "Vintage Swimwear Timeline". Glamoursurf.com. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- "Vintage Swimwear". Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- The Bikini, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Our History Archived 2014-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. speedo.com.au

- Daily News, p. 6

- Meagan Hess. "Skirting the Skirts at the Bathing Beach". Xroads.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- Sandhu, David (August 4, 2003). "Nottingham: Bathed in nostalgia". London: The Telegraph.

- THE 1930s: Sports: Overview Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine, Novel Guide

- Esther Williams, Everything2

- Steven Anzovin & Janet Podell, Famous First Facts, page 51, H.W. Wilson, 2000, ISBN 0-8242-0958-3

- Gayle Kimball, Women's Culture: The Women's Renaissance of the Seventies, page 141, Scarecrow Press, 1981, ISBN 0-8108-1455-2

- Kathleen Morgan Drowne & Patrick Huber, The 1920s, page 104, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, ISBN 0-313-32013-6

- Fashions of 1934 at IMDb

- Samantha Critchell, "Little wonder that bikinis have fit in almost from the start Archived 2008-12-25 at the Wayback Machine", The San Diego Union-Tribune, 2006-05-28

- "Dennis, Clara (Clare) (1916–1971) Biographical Entry". Australian Dictionary of Biography Online. Australian National University. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Daily News, p. 7

- Daily News, p. 8

- "World War II". The Price of Freedom: Americans at War. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Bikini Introduced Archived 2009-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, This Day in History, History Channel

- "Bikini". Fashion Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Claudia Mitchell; Jacqueline Reid-Walsh (2008). Girl Culture: Studying girl culture : a readers' guide Volume 1 of Girl Culture: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 702. ISBN 9780313339097.

- James Kitchling, "Short History of Bikinis and Swimsuits", Articles Central, 2008-08-02

- William Oscar Johnson , "In The Swim", Sports Illustrated, 1989-02-07

- Stevenson, N. J. (2012). Fashion: A visual history from regency & Romance to retro & revolution. New York: The Ivy Press Limited.

- Kennedy, Sarah (2010). The Swimsuit: A History of Twentieth-century Fashions. Carlton Books. ISBN 978-1-84732-382-8.

- Daniel Delis Hill, As Seen in Vogue, page 63, Texas Tech University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-89672-616-9

- Laver, J. (2012). Costume and fashion: A concise history. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Daily News, pp. 9, 12

- Alac, Patrik (2012). Bikini Story. Parkstone International. p. 68. ISBN 978-1780429519.

- "Bikini Styles: Monokini". Everything Bikini. 2005. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Nangle, Eleanore (June 10, 1964). "Topless Swimsuit Causes Commotion". Chicago Tribute. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Campbell, Jule (12 August 1974) Light, Tight And Right For Racing. sportsillustrated.cnn.com

- http://www.cnn.com/2015/05/06/travel/naked-germany/

- Elizabeth Gunther Stewart, Paula Spencer & Dawn Danby, The V Book: A Doctor's Guide to Complete Vulvovaginal Health, page 104, Bantam Books, 2002, ISBN 0-553-38114-8

- overzero.com. "Metroland". Metroland. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- Catalog adds options for overweight girls Article 1 of 1 found, Denver Post, 1992-01-02

- Ellen Shultz, ed. (1986). Recent acquisitions: A Selection, 1985-1986. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 48. ISBN 978-0870994784.

- Elizabeth Gunther Stewart, Paula Spencer and Dawn Danby, The V Book, page 104, Bantam Books, 2002, ISBN 0553381148

- Klaus Honnef, Helmut Newton and Carol Squiers, Portraits: Photographs from Europe and America, page 21, Schirmer, 2004, ISBN 382960131X

- Cathy Horn, "Rudi Revisited", The Washington Post, 1991–11–17, page 03

- Valerie Steele, Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, page 255, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2005, ISBN 0-684-31397-9

- Becky Homan, "Tankini goes over the top", Page 42, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1999-04-03

- Laura Avery, Newsmakers '07: Cumulation page 117, Thomson Gale, 2007, ISBN 0-7876-8091-5

- Rose Apodaca Jones, "Five decades in the swim", WWD, Fairchild Publications, 2001-04-23

- Laura Avery & Thomson Gale, Newsmakers: Cumulation, page 118, Thomson Gale, 2007, ISBN 0-7876-8091-5

- Bridget Quinn, "Stickline: Swimsuit Fashion for Women", Washington Post, 2005-06-22

- Lisa Nakamura, Digitizing Race, page 186, University of Minnesota Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8166-4613-9

- Samantha Critchell, "Cancer charities pink at heart", St. Petersburg Times, 2005-09-29

- A revolutionary swimsuit. European Patent Office (2009)

- Murphy, Sean (19 April 2000) Fastskin fastalk: hype or help? abc.net.au

- Daily News, p. 14

- Nasr, Susan L. Can a swimsuit make you swim faster? science.howstuffworks.com

- TYR Appeals Ban of Arm Bands. collegeswimming.com. 8 June 2004

- Administrator. "Fédération Internationale de Natation - fina.org - FINA GENERAL CONGRESS". fina.org. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- FINA bans hi-tech suits from 2010 BBC, 31 July 2009