Huayna Capac

Huayna Capac, Guayna Cápac, Guayna Capac, Huain Capac,[1] Guain Capac, Guayana Capac[2][3] (in Hispanicized spellings), Wayna Kapa, Wayn Capac,[4] Wayana Qhapaq, Wayna Kapak,[5] Wayna Capac, or Wayna Qhapaq (Quechua wayna boy, young, young man; qhapaq "the mighty one",[6][7] "the young mighty one", "powerful young one"[8] or "powerful youth"[9]) (1464/1468–1524) was the third Sapan Inka of the Inca Empire, born in Tumipampa[10][11] sixth of the Hanan dynasty, and eleventh of the Inca civilization. As other Sapa Inkas, Wayna Qhapaq subjects commonly approached him adding epithets and titles when addressing him, commonly as Wayna Qhapaq Inka Sapa'lla Tukuy Llaqt'a Uya "Unique Sovereign Wayna Qhapaq Listener of All Peoples".[12] His original name was Titu Kusi Wallpa.[9][13] He was the successor to Tupaq Inka Yupanki.[14]:108

| Wayna Qhapaq | |

|---|---|

| Sapan Inka (11th) | |

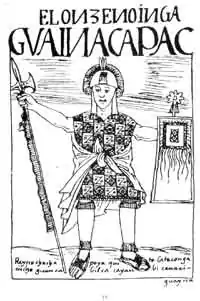

Wayna Qhapaq, drawn by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala. The title, in Poma de Ayala's nonstandard spelling, reads: El onceno inga Guainacapac, "The Eleventh Inca, Guayna Capac". | |

| Reign | 1493–1524 |

| Predecessor | Thupaq Inka Yupanki |

| Successor | Waskar and Atawallpa |

| Born | c. 1468 Tumebamba or Cusco, Peru |

| Died | 1524 Quito |

| Consort | Kuya Kusi Rimay, Kuya Rawa Ukllu |

| Issue | Ninan Kuyuchi, Waskar, Atawallpa, Thupaq Wallpa, Manko Inka Yupanki, Atoq, Paullu Inka, Kispi Sisa, Konono, and others |

| Native Language | Runa Simi, Qhapaq Simi |

| House | Tumipampa Ayllu |

| Dynasty | Hanan Qusqu |

| Father | Inka Thupaq Yupanki |

| Mother | Kuya Mama Ukllu |

Background and family

The exact place and date of Wayna Qhapaq's birth are unknown. Though he was raised in Cusco, he may have been born in 1468 in Tumebamba (modern Cuenca) and have spent part of his childhood there.[15][16][17][18] He was the son of Thupaq Inka (ruled 1471-1493) who had extended Inca rule north into present-day Ecuador, a process continued by Wayna Qhapaq.[19][20]

Wayna Qhapaq's first wife was his full sister, Koya "Queen"[21] Kusi Rimay.[22] The couple produced no male heirs but Wayna Qhapaq sired more than 50 sons and about 200 children[23]:113 with other women. Wayna Qhapaq took another sister, Rawa Okllo, as his royal wife. They had a son called Thupaq Kusi Wallpa,[9] also known as Waskar.

Other sons included Ninan Kuyuchi (the Crown Prince), Atawallpa, Thupaq Wallpa, Manko Inka, Paullu Inka, Atoq, Konono, Wanka Auqui, Kizu Yupanqui, Tito Atauchi, Waman Wallpa, Kusi Wallpa, Tilka Yupanqu.[23]:109-112 Some of them later held the title of Sapan Inka, although some were installed by the Spaniards.

Among the daughters of Wayna Qhapaq were Azarpay (the First Princess of the Empire), Kispe Sisa, Kura Okllu, Marca Chimbo, Pachacuti Yamqui, Miro, Kusi Warkay, Francisca Coya[24][25] and others.[23]:112[14]:112,118

In addition to Kusi Rimay and Rawa Okllo, Wayna Qhapaq had more than 50 wives including Osika, Lari, Anawarque, Kontarwachu and Añas Qolque.[5]:143[23]:109-112

Administration

As a "boy chief" or "boy sovereign", Wayna Qhapaq had a tutor, Wallpaya,[9]:218 a nephew of Inka Yupanki. This tutor's plot to assume the Incaship was discovered by his uncle, the Governor Waman Achachi, who had Wallpaya killed.[14]:109

In the south, Wayna Qhapaq continued the expansion of the Inca Empire into present-day Chile and Argentina and tried to annex territories towards the north in what is now Ecuador and southern Colombia.

In Ecuador, formerly known as the Kingdom of Quito, Wayna Qhapaq absorbed the Quito Confederation into the Inca Empire after marrying the Quito Queen Paccha Duchicela Shyris XVI in order to halt a long protracted war. From this marriage Atawallpa was born (1502 AD) in Caranqui, Ecuador. Atawallpa was to inherit the Kingdom of Quito, by the will of his father Wayna Qhapaq, and later Inca Emperor after defeating his brother, the Inca Emperor Waskar in the Inca Civil War, where Waskar Inka attempted to conquer the Kingdom of Quito after seven years of peace. Wayna Qhapaq became fond of Ecuador and spent most of his time there, founding cities like Atuntaqui. The capital of the empire was in Cuzco, and Wayna Qhapaq rebuilt Quito to make it the "second capital" of the empire.[26]

As Sapa Inca, he also built astronomical observatories in Ecuador such as Ingapirca. Wayna Qhapaq hoped to establish a northern stronghold in the city of Tumebamba, Ecuador, where the Cañari people lived. In the Sacred Valley, the sparse remains of one of Wayna Qhapaq's estates and his country palace called Kispiwanka[27] can still be found in the present-day town of Urubamba, Peru.

In present-day Bolivia, Wayna Qhapaq was responsible for developing Cochabamba as an important agriculture and administrative center, with more than two thousand silos (qollas) for corn storage built in the area.[28] Further north in Ecuador, Wayna Qhapaq's forces attempted to expand into the lowlands of the Amazon basin, reaching the Chinchipe River, but they were pushed back by the Shuar.[29]

Wayna Qhapaq acquired a special fondness for the central Peruvian Andes and its local highlights; he is recorded as having spent time relaxing in the Chinchaycocha lake on the Bombon plateau. Many Inca raft vessels were brought to the lake directly from Ecuador for his amusement.[30]

On its way to Cusco, after Wayna Qhapaq's death in Quito, the procession carrying his body stopped in the vicinity of Shawsha, a city in the central Peruvian Andes, acknowledging the fondness for the area that he had felt for the region and because the local inhabitants had been some of the most loyal to its causes.

The Inca empire reached the height of its size and power under his rule, stretching over much of present-day Bolivia, Peru, Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, and southwestern Colombia. It included varying terrain from high frozen Andes to the densest swamps. His subjects spanned more than two hundred distinct ethnic groups, each with their own customs and languages. The empire spanned 3,500 kilometres (2,200 mi) north to south comprising the Pacific Ocean coast on the west and the Andes in the southeast and the Amazon Basin on the east.[31]

Despite the geographical and cultural challenges, The Inca Empire or Tawantinsuyu ("the united four regions") was sophisticated for its time and place. At its height, it had monumental cities, temples, marvellously-engineered fortresses of stone, roads cut through granite mountain slopes, and massive agricultural terraces and hydraulic works. A dedicated ruler, Wayna Qhapaq did much to improve the lives of his people. In addition to building temples and other works, Wayna Qhapaq greatly expanded the road network.[32]:144 He had storehouses (qollqas) built along it for food so that aid could be quickly rushed to any who were in danger of starvation.

Wayna knew of the Spanish arrival off the coast of his empire[14]:131 as early as 1515.

Death and legacy

Wayna Qhapaq died in 1524.[33]:82–83,85 When Wayna returned to Quito he had already contracted a fever while campaigning in present-day Colombia (though some historians dispute this),[34] likely resulting from the introduction of European disease like measles or smallpox, [14]:117[35]:115 The Spaniards had carried a wide variety of deadly diseases to North, Central and South America; and the Native Americans had no acquired immunity against them. Millions of Central- and South Americans died in that epidemic including Wayna's brother, Auqui Tupac Inca, and Wayna's would-be successor and eldest son, Ninan Kuyuchi. His sons Atawallpa Inka and Waskar Inka were granted two separate realms of the Inka Empire: his favorite Atawallpa, the northern portion centered on Quito; and his legitimate heir Waskar, the southern portion centered on Cuzco.[32]:146 The two sons reigned peacefully for four to five years before Waskar Inka had second thoughts.[33]:89

Waskar quickly secured power in Cuzco and had his brother arrested but Atawallpa escaped from his imprisonment with the help of his wife. Atawallpa began securing support from Wayna Qhapaq's best generals, Chalkuchimac and Quizquiz, who happened to be near Quito, the nearest major city. Atawallpa rebelled against his brother and won the ensuing civil war and imprisoned Waskar at the end of the war.[33]:89–94

Pizarro and his men had the good fortune of ascending into the Andes just as Atawallpa was returning to Cuzco after the successful conclusion of his northern campaigns. After launching a surprise attack in Cajamarca and massacring upward of 6,000 Incan soldiers, Pizarro took Atawallpa prisoner. To secure his release, Atawallpa pledged to fill a room of approximately 88 cubic meters with precious golden objects, the famous Atawallpa's Ransom Room. Over the next months, trains of porters carted precious objects from across the empire. These including jars, pots, vessels, and huge golden plates pried off the walls of the Sun Temple of Qurikancha in Cuzco. On May 3, 1533, Pizarro ordered the vast accumulation of golden objects melted down, a process that took many weeks. Finally, on July 16, the melted loot was distributed among his men. Ten days later, Pizarro had Atawallpa executed.

Lost mummy

All the Inca emperors had their bodies mummified after death. Wayna Qhapaq's mummy was on display in his palace in Cuzco and was viewed by the Spanish conquistadors of the Inca Empire. Later, it was taken from Cuzco to his royal estate of Kispiwanka where it was hidden from the Spanish by Wayna Qhapaq's relatives and servants. At some point it was taken back to Cuzco, where it was discovered in 1559 by the Spanish. Along with mummies of 10 other Inca emperors and their wives, the mummy was taken to Lima where it was displayed in the San Andres Hospital. The mummies deteriorated in the damp climate of Lima and eventually they were either buried or destroyed by the Spanish.[36]

An attempt to find the mummies of the Inca emperors beneath the San Andres hospital in 2001 was unsuccessful. The archaeologists found a crypt, but it was empty. The mummies may have been removed when the building had been repaired after an earthquake.[37]

References

- Echard, Lawrence (1815). Diccionario geografico universal: O-S (in Spanish). por Francisco Martínez Dávila.

- Humboldt, Alexander von; Rebok (ed.), Sandra (2011). Cosmos: ensayo de una descripción física del mundo (in Spanish). Editorial CSIC - CSIC Press. ISBN 9788400093082.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Portnoy, Nestor F. (1997). Estudio en tradicion oral: "Sobre la vida del Inca Guayana Capac" (in Spanish). Publisher not identified.

- Silverman-Proust, Gail. "The Woven Shadow of Time: Four Inti Mofits from Q'ero" (PDF). Dialogo Andino N°6 - 1987: 117. ISSN 0716-2278.

“Wayn Capac kay pachala riki puntata chinkaypushan". (In this world, Wayna Capac sets into a mountain peak. (Taped 1985).

- Ellefsen, Bernardo (1989-01-01). Matrimonio y sexo en el incario (in Spanish). Editorial Los Amigos del Libro. p. 143. ISBN 9788483701560.

Dos casos notables se refieren a las concubinas de Wayna Kapak: Kontarwacho y Añas Kolke, ambas de la etnia huaylla.

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary): wayna. - adj. s. m. Joven. Hombre que está en la juventud. qhapaq. - adj. Principal. Primero en importancia. || Noble, ilustre. Qhapaq. / Rico, -ca. Noble, adinerado. / adj. y s. Poderoso, -sa. Acaudalado, adinerado. || El que tiene extensas tierras.

- Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua, Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco, Cusco 2005: qhapaq - s. Hist. Término utilizado en el inkanato para denominar al poderosos, ilustre, eminente, regio, próspero, glorioso, de sangre real, etc. ...

- Graziano, Frank; Graziano, John D. MacArthur Professor of Hispanic Studies Frank (1999). The Millennial New World. Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780195124323.

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (2014-05-27). The Incas. John Wiley & Sons. p. 6. ISBN 9781444331158.

- "Biography of Huayna Capac o Huaina Capac. Emperador inca". TheBiography.com. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- "Huayna Capac". mayaincaaztec.com. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- Conocimiento indígena y globalización (in Spanish). Editorial Abya Yala. 2005. p. 41. ISBN 9789978223864.

- de Gamboa, Sarmiento (2007). Bauer, Brian S.; Smith, Vania (eds.). The History of the Incas. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 173.

- de Gamboa, P.S., 2015, History of the Incas, Lexington, ISBN 9781463688653

- Rostworowski, Maria. Enciclopedia Temática del Perú (in Spanish). 1. p. 67.

- Cabello Valboa, Miguel (1945). Miscelánea Antártica (in Spanish). pp. 142, 143, 146.

- de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui, Juan (1879) [c. 1620]. Jiménez de la Espada, Marcos (ed.). Relación de las antigüedades deste Reyno del Pirú (in Spanish). pp. 249, 255.

- Cobo, Bernabé (1964) [1890]. Historia del Nuevo Mundo (in Spanish). 2. p. 90.

- Niles, Susan A. (1999). The Shape of Inca History. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 253.

- de Gamboa, Sarmiento (2007). Bauer, Brian S.; Smith, Vania (eds.). The History of the Incas. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 171.

- Cadena, María Soledad De la (1996). Race, ethnicity, and the struggle for indigenous self-representation: de-indianization in Cuzco, Peru, 1919-1992. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 292.

The sacred animals, royal servants, the Virgins of the Sun, the priests, the high dignitaries of the Court, the Koya (Queen) and the Inca paraded through the scene, these last occupying their respective seats of honor.

- Niles, Susan (May 1, 1999). The Shape of Inca History: Narrative and Architecture in an Andean Empire. University Of Iowa Press. p. 109. ISBN 0877456739.

- Niles, Susan A. (1999). The Shape of Inca History: Narrative and Architecture in an Andean Empire. University of Iowa Press. ISBN 9781587292941.

- http://biblioteca.culturaypatrimonio.gob.ec/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=114417

- https://www.academia.edu/10355786/Descendientes_del_Emperador_Inca_Pachac%C3%BAtec

- http://www.antonioante.gob.ec/web/?page_id=7%5B%5D

- Saintenoy, Thibault. "Choqek'iraw et la vallée de l'Apurimac : paysages et sociétés préhispaniques tardives". HTTP WWW Theses Fr.

- García Mérida, Wilson. "Huayna Capac, el inca que fundó Cochabamba". Voltairenet.org (in Spanish). Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- Ernesto Salazar (1977). An Indian federation in lowland Ecuador (PDF). International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 13. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- El *Peru: 1 (in Spanish). 1876.

- "Maya, Aztecs, Inca, Inuit: before Columbus." Archived 2011-03-20 at the Wayback Machine Worldwide Story for Civilization. (retrieved 3 July 2011)

- Prescott, W.H., 2011, The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142

- de la Vega, G., "El Inca", 2006, Royal Commentaries of the Incas and General History of Peru, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Co., Inc., ISBN 9780872208438

- McCaa; et al. "Why Blame Smallpox? The Death of the Inca Huayna Capac and the Demographic Destruction of Tawantinsuyu (Ancient Peru)". Retrieved 7 Jan 2012.

- Leon, P., 1998, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, Chronicles of the New World Encounter, edited and translated by Cook and Cook, Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822321460

- McCaa, Robert, Nimlos, Aleta, and Hampe Martinez, Teodoro (nd) "Why Blame Smallpox"; http://users.pop.umn.edu/~rmccaa/aha2004/why_blame_smallpox.pdf, accessed 27 Jan 2017; Pringle, Harriet (2011), "Inca Empire", National Geographic, http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/04/inca-empire/pringle-text/2, accessed 27 Jan 2017

- Pringle, Harriet

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Huayna Capac. |

| Library resources about Huayna Capac |

- Sarmiento de Gamboa, Pedro. The History of the Incas. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-292-71485-4.

| Preceded by Topa Inca Yupanqui |

Sapa Inca As ruler of the Inca Empire 1493–1527 |

Succeeded by Huáscar (see also Ninan Cuyochi) |