Hydroelectric power in the United States

Hydroelectric power in the United States is, as of 2019, the second-largest renewable source of energy in both generation and nominal capacity (behind wind power).[1] In 2019, hydroelectric power produced 38% of the total renewable electricity, and 6.6% of the total U.S. electricity.[2]

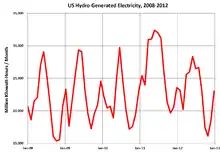

According to the International Hydropower Association the United States was the 3rd largest producer of hydroelectric power in the world in 2020 after Brazil and China. Total installed capacity for 2020 was 102,8 GW. The installed capacity was 80 GW in 2015. The amount of hydroelectric power generated is strongly affected by changes in precipitation and surface runoff.[3]

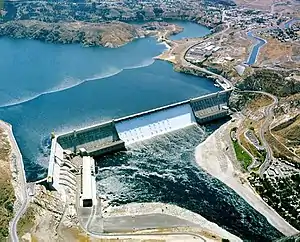

Hydroelectric stations exist in at least 34 US states. The largest concentration of hydroelectric generation in the US is in the Columbia River basin, which in 2012 was the source of 44% of the nation's hydroelectricity.[4] Hydroelectricity projects such as Hoover Dam, Grand Coulee Dam, and the Tennessee Valley Authority have become iconic large construction projects.

Of note, however, is that California does not consider power generated from large hydroelectric facilities (facilities greater than 30 megawatts) to meet its strictest definition of "renewable", due to concerns over the environmental impact of large hydroelectric projects. As such, electricity generated from large hydroelectric facilities does not count toward California's strict Renewable Portfolio Standards. Roughly about 10 to 15 percent of California's energy generation is from large hydroelectric generation that is not RPS-eligible.[5]

The significant impact of dams on the power sector, water use, river flow, and environmental concerns requires significant policy specific to hydropower.

History

The earliest hydroelectric power generation in the U.S. was utilized for lighting and employed the better understood direct current (DC) system to provide the electrical flow. It did not flow far however, with ten miles being the system's limit; solving electricity's transmission problems would come later and be the greatest incentive to the new hydroelectric water-power developments.[6]

The first DC powerhouse was in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where the water turbine at the Wolverine Chair factory was attached to a dynamo using a mechanical belt drive to illuminate sixteen street lights.[7][8] This occurred in 1880, the same year Thomas Edison produced the long-lasting incandescent filament light bulb, which was a safety and convenience improvement over existing candles, whale oil lamps and kerosene lamps inside buildings. In 1881, also using DC for lighting at Niagara Falls, Jacob F. Schoellkopf diverted part of the output from his waterwheel-powered flour mills to drive one of Charles Brush's improved generators to provide nighttime illumination for the tourists. Previously the attraction had been illuminated by burning bright calcium flares but arc-lights proved a better and cheaper alternative. In 1882, the world's first commercial central DC hydroelectric power plant provided power for a paper mill in Appleton, Wisconsin;[9] just months later the first investor-owned electric utility, Edison Illuminating Company, completed the first fossil fueled electrical power plant in New York City, to compete with hydroelectric power close to an area of high demand. By 1886, between 40 and 50 hydroelectric stations were operating in the United States and in Canada, and by 1888 about 200 electric companies relied on hydropower for at least part of their generation.[8]

Recognizing that the great hydroelectric potential of the Falls exceeded the local demand for electricity, a large power company was established nonetheless at the prime location for development; it awaited the prospect of an effective long-distance power transmission system. Westinghouse Electric won the competition, developing their plans around an alternating current system. The station was completed in 1895 and in 1896, electricity transmission 20 miles away to Buffalo, New York began. This event also began the rise to dominance of the AC system over Thomas Edison's direct current methods. Multiple permanent hydropower stations still exist on both the American and Canadian sides of the Falls, including the Robert Moses Niagara Power Plant, the third largest in the United States.

The need to provide rural development in the early 20th century was often coupled to the availability of electric power and led to large-scale projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority which created numerous dams and, sometimes controversially, flooded large areas. In the 1930s, the need for power in the Southwest led to the building of the largest concrete construction in the world at that time, the Hoover Dam. The Grand Coulee Dam was both a power and irrigation project of the 1930s that was expanded for military industrial reasons during World War II which also saw other dams such as the TVA's Fontana Dam built.

Dam building peaked in the 1960s and few dams were built in the 1970s. The growing awareness of environmental issues with dams saw the removal of some older and smaller dams and the installation of fish ladders at others. The enormous Rampart Dam was canceled in 1967 due to environmental and economic concerns. Instead of new dams, repowering old stations has increased the capacity of several facilities. For instance, Hoover Dam replaced its generators between 1986 and 1993. The need to alter downstream waterflow for ecological reasons (eliminating invasive species, sedimentation, etc.) has led to regulated seasonal drawdowns at some dams, changing the availability of water for power generation. Droughts and increased agricultural use of water can also lead to generation limits.

According to a United States Department of Energy report,[10] there exists over 12,000MW of potential hydroelectricity capacity in the US existing 80,000 unpowered dams. Harnessing the currently unpowered dams could generate 45 TWhr/yr, equivalent to 16 percent of 2008 hydroelectricity generation.

Pumped storage

Another application of hydroelectricity is Pumped-storage hydroelectricity which does not create a net gain in power but enables peak demand balancing. Water is pumped from a lower elevation source into a higher one and only released through generators when electric demand is high. In 2009 the United States had 21.5 GW of pumped storage generating capacity, accounting for 2.5% of baseload generating capacity.[11] Bath County Pumped Storage Station is the largest such facility in the world. Other stations of this type include Raccoon Mountain Pumped-Storage Plant, Bear Swamp Hydroelectric Power Station and Ludington Pumped Storage Power Plant on Lake Michigan and previously the largest in the world.

Tidal power

No significant tidal power plants exist in the United States. A project was proposed and run by the Snohomish County PUD in Washington but was ended when trouble was encountered obtaining enough funding.[12]

Largest hydroelectric power stations

This is a list of the ten largest hydroelectric power stations in the United States by installed capacity.

| Rank | Name | Image | Capacity (MW) |

State | Coordinates | Opening Year | Type | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Grand Coulee |  |

6,809 | 47°57′21″N 118°58′54″W | 1942 | Reservoir (95.4%) Pumped-storage (4.6%) |

[13] | |

| 2 | Bath County | 3,003 | 38°13′50″N 79°49′10″W | 1985 | Pumped-storage | [14] | ||

| 3 | Robert Moses Niagara |  |

2,675 | 43°08′35″N 79°02′23″W | 1961 | Reservoir | ||

| 4 | Chief Joseph |  |

2,614 | 47°59′43″N 119°38′00″W | 1979 | Run-of-the-river | [15] | |

| 5 | John Day |  |

2,485 | 45°42′59″N 120°41′40″W | 1971 | Run-of-the-river | [16] | |

| 6 | Ludington | .jpg.webp) |

2,172 | 43°53′37″N 86°26′43″W | 1973 | Pumped-storage | [17] | |

| 7 | Hoover |  |

2,080 | 36°0′56″N 114°44′16″W | 1936 | Reservoir | [18] | |

| 8 | The Dalles |  |

1,813 | 45°36′44″N 121°08′04″W | 1957 | Run-of-the-river | [19] | |

| 9 | Raccoon Mountain |  |

1,616 | 35°2′54″N 85°23′48″W | 1978 | Pumped-storage | [20] | |

| 10 | Castaic |  |

1,500 | 34°35′14″N 118°39′24″W | 1973 | Pumped-storage | [21] | |

Energy generation

| Year | Summer capacity (GW) |

Electricity generation (TWh) |

Capacity factor | Yearly growth of generating capacity |

Yearly growth of produced energy |

Portion of renewable electricity |

Portion of total electricity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 79.85 | 273.7 | |||||

| 2018 | 79.89 | 291.72 | 0.417 | 0.12% | -2.7% | 40.9% | 7.0% |

| 2017 | 79.79 | 300.05 | 0.430 | -0.2% | 12% | 43.7% | 7.44% |

| 2016 | 79.92 | 267.81 | 0.383 | 0.3% | 7.50% | 43.9% | 6.57% |

| 2015 | 79.66 | 249.08 | 0.357 | 0.56% | -4.0% | 45.77% | 6.11% |

| 2014 | 79.24 | 258.75 | 0.373 | 0.05% | -3.66% | 47.93% | 6.32% |

| 2013 | 79.22 | 268.57 | 0.387 | 0.64% | -2.78% | 51.44% | 6.61% |

| 2012 | 78.7 | 276.24 | 0.401 | 0.06% | -13.50% | 55.85% | 6.82% |

| 2011 | 78.65 | 319.36 | 0.464 | -0.23% | 22.74% | 62.21% | 7.79% |

| 2010 | 78.83 | 260.2 | 0.377 | 0.39% | -4.85% | 60.88% | 6.31% |

| 2009 | 78.52 | 273.45 | 0.398 | 0.76% | 7.31% | 65.47% | 6.92% |

| 2008 | 77.93 | 254.83 | 0.373 | 0.05% | 2.96% | 66.90% | 6.19% |

| 2007 | 77.89 | 247.51 | 0.363 | 0.09% | -14.43% | 70.18% | 5.95% |

| 2006 | 77.82 | 289.25 | 0.424 | 0.36% | 7.00% | 74.97% | 7.12% |

| 2005 | 77.54 | 270.32 | 0.398 | -0.13% | 0.71% | 75.57% | 6.67% |

| 2004 | 77.64 | 268.42 | 0.395 | -1.33% | -2.68% | 76.36% | 6.76% |

| 2003 | 275.8 | ||||||

| 2002 | 264.33 | ||||||

| 2001 | 216.96 | ||||||

| 2000 | 275.57 |

See also

- Renewable energy in the United States

- List of reservoirs and dams in the United States

- List of the tallest dams in the United States

- List of dams in the Columbia River watershed

- Tennessee Valley Authority

- Electricity sector in the United States

- Wind power in the United States

- Solar power in the United States

- Geothermal energy in the United States

- Biofuels in the United States

- List of renewable energy topics by country

References

- Renewable Tuesday: US Wind Surpasses Hydro

- "Hydropower explained - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 2020-10-24.

- US Energy Information Administration (January 2010) Electric Power Annual 2008, DOE/EIA-0348(2008), p.2-3, PDF file, downloaded 24 January 2010.

- US Energy Information Administration, “The Columbia River Basin provides more than 40% of total US hydroelectric generation”, Today in Energy, 27 June 2014.

- http://www.energy.ca.gov/renewables/tracking_progress/documents/renewable.pdf

- Engr. W. E. Herring, U. S. Forest Service, Applications of Water Power. Included in the Preliminary Report of the Inland Waterways Commission, submitted to Congress by Theodore Roosevelt, February 26, 1908. "The application of great water powers to the industrial wants of distant cities is less than ten years old and is still in its infancy, yet in this short space of time stations supplying a large number of cities in the United States with a combined capacity of hundreds of thousands of horsepower have been installed. To reach these industrial centers the water power is electrically transmitted, and in many cases the distance is over 100 miles. This method of utilizing water power has been made possible only by long distance transmission. Fifteen years ago 10 miles was the limit to which electrical power could be transmitted, but at the present time 150 miles is very common and in one case a line of 200 miles is in use. This fact has been the greatest incentive to such water-power developments."

- Energy Timelines Hydropower, Department of Energy

- History of Hydropower Archived 2010-01-26 at the Wayback Machine Wind and Water Power Program, Department of Energy

- Hydroelectric Power "The first commercial hydroelectric power station was built in 1882 on the Fox River in Appleton, Wisconsin, in order to provide 12.5 kilowatts of power to light two paper mills and a residence. Paper manufacturer H. F. Rogers developed the station after seeing Thomas Edison's plans for an electricity power station in New York."

- https://www.energy.gov/articles/energy-dept-report-finds-major-potential-grow-clean-sustainable-us-hydropower

- http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/servicerpt/stimulus/excel/aeostimtab_9.xls

- "Tidal Energy Research | Power Supply | Snohomish County PUD". www.snopud.com. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- "Grand Coulee Dam - Hydroelectric Project Information | Columbia Basin Research". www.cbr.washington.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "Bath County Pumped Storage Station | Dominion Energy". www.dominionenergy.com. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "Chief Joseph Dam - Hydroelectric Project Information | Columbia Basin Research". www.cbr.washington.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "John Day Dam - Hydroelectric Project Information | Columbia Basin Research". www.cbr.washington.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- Network, Michael McCluskey / Energy News. "Michigan utilities upgrade pumped storage plant ahead of renewable push". Energy News Network. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "Hoover Dam | Bureau of Reclamation". www.usbr.gov. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- "The Dalles Dam - Hydroelectric Project Information | Columbia Basin Research". www.cbr.washington.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- "TVA - Raccoon Mountain". www.tva.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- "Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Energy Storage Development Plan: Description of Existing and Eligible Energy Storage System" (PDF). LADWP. September 2, 2014. p. 7-8. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Electric Power Monthly". US Energy Information Administration.

- "Electric Power Annual". US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- "EIA - Electricity Data". US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 2020-05-20.

- Renewable Energy: U.S. hydropower generation 2019