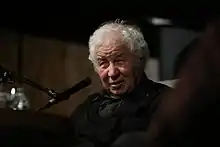

Ilya Kabakov

Ilya Iosifovich Kabakov (Russian: Илья́ Ио́сифович Кабако́в; born September 30, 1933), is a Russian–American conceptual artist,[1] born in Dnipropetrovsk in what was then the Ukrainian SSR of the Soviet Union. He worked for thirty years in Moscow, from the 1950s until the late 1980s. He now lives and works on Long Island, United States.

Ilya Kabakov | |

|---|---|

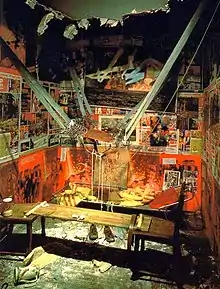

.jpg.webp) Ilya Kabakov gives instructions for the installation "The Man Who will Fly into Space From His Apartment" | |

| Born | September 30, 1933 |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Known for | Installation art |

| Spouse(s) | Emilia |

Throughout his forty-year plus career, Kabakov has produced a wide range of paintings, drawings, installations, and theoretical texts—not to mention extensive memoirs that track his life from his childhood to the early 1980s. In recent years, he has created installations that evoked the visual culture of the Soviet Union, though this theme has never been the exclusive focus of his work. Unlike some underground Soviet artists, Kabakov joined the Union of Soviet Artists in 1959, and became a full member in 1962. This was a prestigious position in the USSR and it brought with it substantial material benefits. In general, Kabakov illustrated children's books for 3–6 months each year and then spent the remainder of his time on his own projects.

By using fictional biographies, many inspired by his own experiences, Kabakov has attempted to explain the birth and death of the Soviet Union, which he claims to be the first modern society to disappear. In the Soviet Union, Kabakov discovers elements common to every modern society, and in doing so he examines the rift between capitalism and communism. Rather than depict the Soviet Union as a failed Socialist project defeated by Western economics, Kabakov describes it as one utopian project among many, capitalism included. By reexamining historical narratives and perspectives, Kabakov delivers a message that every project, whether public or private, important or trivial, has the potential to fail due to the potentially authoritarian will to power.

Early life

Ilya Iosifovich Kabakov was born on September 30, 1933 in Dnipropetrovsk, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. His mother, accountant Bertha Judelevna Solodukhina, and his father, locksmith Iosif Bentcionovitch Kabakov, were Jewish. Ilya was evacuated during World War II to Samarkand with his mother. There he started attending the school of the Leningrad Academy of Art that was evacuated to Samarkand. His classmates included the painter Mikhail Turovsky.

Education

From 1945 to 1951, he studied at the Art School, Moscow; in 1957 he graduated from V.I. Surikov State Art Institute, Moscow, where he specialized in graphic design and book illustration.

Career

In 1959, Kabakov became a "candidate member" of the Union of Soviet Artists (he later became a full member in 1962). This status secured him a studio, steady work as an illustrator and a relatively healthy income by Soviet standards. He recalls that he was "rich" compared to most Soviets.

"Official" vs. "unofficial" artists

Kabakov, as a book illustrator and official artist, was able to produce his "private" artwork in his official studio. Between 1953-1955 Kabakov began making his first unofficial works, which he called "drawings for myself." The phrase "drawings for myself" serves as a title for the works and an explanation. None of these early projects amounted to more than sketches on paper. They were never titled, and they were often similar in style to his book illustrations. Throughout his career the tension between official labor and unofficial art would haunt Kabakov.

End of the "Thaw"

In 1962, there was an exhibition at the Moscow Artists’ Union that occasioned Nikita Khrushchev’s infamous attacks on modern art. The incident ended the Thaw Era that had begun in 1956. That same year Kabakov produced several series of ‘absurd drawings.’ These were eventually published in a 1969 Prague magazine. Prior to this, however, Kabakov had his first taste of publicly challenging the Soviet regime. In 1965 a member of the Italian Communist Party exhibited a number of works by Soviet artists in L'Aquila, Italy. The goal of the show was to prove that the Soviet Union had a more diverse culture than was known to the West and even to the Soviet people. Kabakov lent a series of drawings titled Shower.

The Shower Series

In the original Shower series from 1965, a man is depicted standing under a shower but with no water. Kabakov interpreted the work as a simple but universal metaphor about the individual who is always waiting for something, but never receives anything. Instead, the Italians and critics of communism interpreted the work as signifying Soviet culture and its lack of material reward. The publicity Kabakov received prevented him from getting work as an illustrator for four years, forcing him to work under someone else’s name. The use of an alter ego would become a common tool in Kabakov’s unofficial artwork.

The Sretensky Boulevard Group

A group of artists that lived on Sretensky Boulevard became loosely associated by their like-minded ideas in the late 1960s. Primarily identified as Kabakov, Eduard Steinberg, Erik Bulatov, Viktor Pivovarov and Vladimir Yankilevsky, the group also included Oleg Vassiliev, Ülo Sooster and others with the same pre-occupation. The artist's studios were also used as venues to show and exchange ideas about unofficial art. The majority of visual artists who became part of the 'Sretensky Boulevard Group' worked officially as book illustrators and graphic designers. They were in strong contrast to a group called the 'Lianozovo Group' artists, a loose group around Oscar Rabin, who were primarily abstractionists. This group in particular was often harassed and in some cases imprisoned or exiled. It is apparent that Kabakov and his associates were conformist as a survival strategy, a tactic which began at the art academies. Kabakov reports that during school and throughout his early career he did everything expected of him and, on the surface, accepted the Soviet reality.

The Russian Series

It was at the studio on Sretensky Boulevard that Kabakov’s unofficial work took a new turn. Previously, his work consisted of relatively modest-sized drawings of approximately 8 x 11 inches. Here, he began to create considerably larger works. The Russian Series, 1969, consists of three paintings. All are 49 x 77 inches and are covered with a sandy brown. Within each, there are minute details and objects alternatively on the surface or hidden beneath the sandy color. The details interrupt the viewer’s gaze, which would otherwise be overwhelmed by the color of the brown enamel. The Russian Series is a prototype for Kabakov’s later works because the paintings are accompanied by text.

In all three works of The Russian Series the details are located in the corners or away from the center. The wholeness of the “sandy color, that of soil” is left intact, interrupted in a discrete manner almost secretively or mistakenly. Yet the dominance of the center overpowers the viewer, returning his gaze to the middle and away from the discrepancies in color. Kabakov would repeat this strategy from 1983-1988 with a second series called Three Green Paintings. In this series, rather than depict objects, he placed texts on the upper left and right hand corners of what is otherwise a field of green enamel paint.

Kabakov described the colors of paint in The Russian Series and Three Green Paintings as the main characters. The brown sandy soil color of the first series was the same enamel used in the Soviet Union during the 1950s and 1960s to paint everything from roofs to hallways, but most often floors. Kabakov points out that the color of the state is red but the color of the country is gray, due to its “humdrum existence”. Kabakov assigns these colors a metaphysical meaning of earth and nature as controlled and depicted by the Soviet state. He then suggests that if you mix these two colors you end up with the brown sandy soil color, which signifies both the floors and the ground that support the feet of the populace of the Soviet Union. The green of the second series is enamel that was used to paint the lower part of the walls up to one meter high in order to protect them from dirt and scuffs. For Kabakov, these colors evoke feelings of unavoidable hopelessness. More pertinent to this argument is what these series of paintings do not address. Political ideology is absent and only impersonal colors exist to dominate minor features, all of which are faceless texts and objects.

The Fly

Throughout the 1960s, Kabakov’s work became more experimental and irregular. Some of his best-known motifs begin to develop in this decade. For example, Queen Fly of 1965 is a smaller and quite unique work in that a decorative, semi-geometric design covers a plywood base and frame. However the fly, a lone element separate from the painted pattern, is also the main character, and one that reoccurs throughout Kabakov’s oeuvre.

The fly motif is so important that it remained in his work until after he moved to the West. The 1992 installation in Cologne, Life of Flies, consists of several halls in which the economy, politics, culture, and an entire civilization, specifically the Soviet Union, are associated with flies. The civilization has an atmosphere so boring that flies die from it. Throughout Kabakov’s oeuvre the flies represent two seemingly different themes: human lives and garbage.

The 1970s

In the 1970s, several factors led Kabakov to become more conceptually oriented. The first was the Soviet intelligentsia’s adoption of the structuralist theory from France, which helped shift interest from art object to its context. Next, perhaps in part due to the influence of structuralism, the intelligentsia began to question the friend-or-foe attitude toward Soviet ideology. Dissident artists and intellectuals began to be seen by Russian structuralists as supporting the gulf within society and between the industrialist societies of the East and West. In the 1970s, rather than be anti-Soviet and pro-Western, many artists took a neutral position that would allow them to question and analyze the perceived gap between the ideologies.

The Moscow Conceptualists

For Kabakov, these developments led to his friends and colleagues forming a group that became known as the Moscow Conceptualists, which developed out of the Sretensky Boulevard Group. It is problematic to determine exactly who was a member of the group, as the term is fluid, broadly encompassing the Sots artists and the Collective Actions group, which both were influential in the construction of Russian conceptualist art.

Albums and Ten Characters

Prior to creating the installations for which Kabakov is known worldwide, Kabakov created fictional albums. He has created a total of 50. Each album is a story about one character who is often able to overcome the banality of everyday existence, or, "of a small man, possessed by big ideas." The first ten albums is a series called Ten Characters (1972–75). In the story of the Ten Characters, a man, attempting to write his autobiography, realizes that nothing much ever happened to him, and most of his life amounted to impressions of people, places, and objects. So he creates ten different characters to explain his perception of the world.

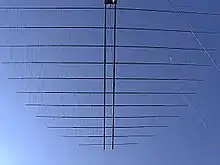

Each story is text with illustration, demonstrating that Kabakov’s official work as a book illustrator is a strong presence in his "unofficial" work as well. In one of the albums from Ten Characters, called The Flying Komarov, average Soviet citizens grasp the wings of undersized versions of airplanes, some being pulled by ropes like water skiers in the sky. The illustrations also depict, in a cartoon-like fashion, the townspeople holding hands and forming large circles while floating in the air. The drawings are highly fanciful and could easily be used for a children’s book, if not in the Soviet Union then certainly in the West. The written explanation, however, suggests a deeper, perhaps more cynical meaning.

Kabakov claims the albums are a genre somewhere between several types of art including literature, fine arts, and cinematography. “Most of all,” he suggests, “the ‘albums’ are a type of ‘domestic theater’…like old theater conducted on a town square in broad daylight". He compares his albums to theater where the viewer is bound by action and darkness, which does not allow for examination and evaluation of the action. The interest in giving the viewer the freedom to interact with and interpret the artwork is central to Kabakov’s oeuvre. None of his works are didactic or attempt to deliver a political statement.

The 1980s

Unlike many Soviet artists who emigrated to the West in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Kabakov remained in Russia until 1987. His first trip to the West was to Graz, Austria when the Kunstverein gave him an artistic residency. Between 1988 and 1992, Kabakov claimed no permanent home yet stayed in the West, working and living only briefly in various countries. In comparison to many Soviet émigré artists, Kabakov was immediately successful and has remained so ever since. Between 1988 and 1989, he had exhibitions in New York City, Bern, Venice, and Paris.

Between 1983 and 2000, Kabakov created 155 installations.

Personal life

In 1989, Kabakov also began working with his niece[2][3] Emilia, who would later become his wife [4] and who emigrated from the USSR in 1975.[5]

Exhibitions and collectors

Following Mikhail Chemiakin's 1995 show, Ilya Kabakov had one of the first major solo exhibitions of a living Russian artist at the new State Hermitage Museum in 2004.

His works are in the collections of the Zimmerli Art Museum, the Centre Pompidou (Beaubourg), Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim, The Hermitage, Tretjakov Gallery (Moscow), Norway Museum Of Contemporary Art, and museums in Columbus, Ohio, Frankfurt, Köln, etc.

In 2017 the Tate Modern in London exhibited Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. set up an exhibition Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Utopian Projects.

References

- https://docs.google.com/gview?a=v&q=cache:ATOKx0bwAOwJ:www.ilya-emilia-kabakov.com/biography.pdf+Ilya+Kabakov+Jewish&hl=en&gl=us

- https://birdinflight.com/ru/pochemu_eto_shedevr/20170706-ilya-kabakov-i-ego-kontseptualnye-zhuki.html

- https://24smi.org/celebrity/66598-ilia-kabakov.html

- https://birdinflight.com/ru/pochemu_eto_shedevr/20170706-ilya-kabakov-i-ego-kontseptualnye-zhuki.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-09-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Alexander Rappaport. The Ropes of Ilya Kabakov: An Experiment in Interpretation of a Conceptual Installation // Tekstura: Russian essays on visual culture / Ed. and translated by A. Efimova and L. Manovich. University of Chicago Press, 1993. — ISBN 0-226-95123-5, ISBN 978-0-226-95123-2

- Stoos, Toni, ed. Ilya Kabakov Installations: 1983-2000 Catalogue Raisonne Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2003, 2 volumes.

- Kabakov, Ilya. 5 Albums, Helsinki: The Museum of Contemporary Art and the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo. Helsinki: ARTPRINT, 1994. ISBN 951-47-8835-4

- Martin, Jean-Hubert and Claudia Jolles. Ilya Kabakov: Okna, Das Fenster, The Window, Bern: Benteli Verlag, 1985.

- Wallach, Amei. Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away, New York: Harry Abrams, 1996.

- Meyer, Werner, ed. Ilya Kabakov: A Universal System for Depicting Everything Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2002.

- Groys, Boris, David A. Ross, Iwona Blaznick. Ilya Kabakov, London: Phaidon, 1998. ISBN 0-7148-3797-0

- Rattemeyer, Volker, ed. Ilya Kabakov: Der rote Waggon, Nurnberg: verlag fur modern kunst, 1999. ISBN 3-933096-25-1

- Kabakov, Ilya. The Communal Kitchen, Paris: Musee Maillol, 1994.

- Kabakov, Ilya. 10 Characters, New York: Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, 1988.

- Osaka, Eriko ed., Ilya Kabakov. Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal (1898–1933), Contemporary Art Center: Art Tower Mito, Japan, 1999, 2 volumes.

- Kabakov, Ilya. Ilya Kabakov on Ulo Sooster's Paintings: Subjective Notes, Tallinn: Kirjastus "Kunst", 1996.

- Kabakov, Ilya and Vladimir Tarasov. Red Pavilion, Venice Biennale Venice: Venice Biennale, 1993.

- Kabakov, Ilya. Life of Flies, Koln: Edition Cantz, 1992.

- Kabakov et al. Ilya Kabakov: Public Projects or the Spirit of a Place, Milan: Charta, 2001, ISBN 88-8158-302-X.

- Groys, Boris (2006). Ilya Kabakov: The Man Who Flew into Space from his Apartment. The MIT Press. ISBN 1-84638-004-9.

- Jackson, Matthew Jesse. The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-226-38941-7

- Ilya Kabakov; Kabakov's Installations

Further reading

- Kabakok, Ilya ed.,On Art University of Chicago Press, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ilya Kabakov. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ilya Kabakov |