Internet in Myanmar

The internet in Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) has been available since 2000 when the first Internet connections were established. Beginning in September 2011, the historically pervasive levels of Internet censorship in Burma were significantly reduced. Prior to September 2011 the military government worked aggressively to limit and control Internet access through software-based censorship, infrastructure and technical constraints, and laws and regulations with large fines and lengthy prison sentences for violators.[1][2][3] In 2015, the internet users significantly increased to 12.6% with the introduction of faster mobile 3G internet by transnational telecommunication companies, Telenor Myanmar and Ooredoo Myanmar, and later joined by national Myanmar Post and Telecommunications (MPT).[4][5] While the internet situation in Myanmar has constantly been evolving since its introduction in 2010 and reduction of censorship in 2011, laws such as the 2013 Telecommunications Law continue to restrict citizens from total freedom online.[6] Despite restrictions, internet penetration continues to grow across the country.

Myanmar's top-level domain is '.mm'.[7]

Access and usage

Service providers

Yatanarpon Teleport,[8] 5BB Broadband, satellite internet provider Skynet,[9] the state-owned Myanmar Post and Telecommunication (MPT), WeLink Myanmar, Myanmar Net, Myanmar Speednet, [10] AGB Communication, Fortune Broadband and Kinetic Myanmar Technology[2] are the Internet service providers in Yangon and Mandalay.[11][12]

Before the democratization in 2011, Internet cafés were common access center for internet users in the country and most use different pieces of software to bypass the government's proxy servers.[3][13][14] The popularity of Internet cafés declined with the emergence of cheap mobile internet with the improvement in telecommunication infrastructure following the liberalization. However, they are still widely present, especially in Yangon and Mandalay and are used extensively for blogging and other activities. Internet on mobile devices are widely used today.

Internet in other towns and rural areas

The internet access for home use in other towns except Yangon and Mandalay is only available through ADSL technology, provided by MPT. However, the pricing is prohibitively expensive for most customers. For ADSL, MPT's fixed-line phone (new installation) price is 325,000 Myanmar Kyat (US$240 estimated) in 2017. MPT's ADSL Initial Setup Fee is 50,000 Myanmar Kyat (US$37 estimated) without a CPE. Annual Fee is 50,000 Myanmar Kyat (US$37 estimated), and Monthly fee for 512kbit/s (lowest bandwidth) is 17,000 Myanmar Kyat (US$13 estimated) and fee for 2.5Mbit/s (highest bandwidth) is 80,000 Myanmar Kyat (US$60 estimated). FTTH internet is not available in towns.

Internet penetration

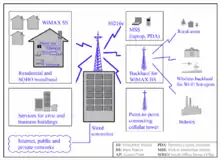

Myanmar has a very low Internet penetration rate due to government restrictions on pricing and deliberate lack of facilities and infrastructure.[15] According to World Internet Stats statistics as of June 2012, the country had over 534,930 Internet users (1.0% of the population) with the vast majority of the users hailing from the two largest cities, Yangon and Mandalay.[16] Although 42 cities across the country have access to the Internet, the number of users outside Yangon and Mandalay is just over 10,000. In 2012, most of the country's 40,000 Internet connections were ADSL circuits, followed by dial-up, satellite terminal, and WiMax. MPT is also undertaking a trial of fibre-to-the-home in Mandalay, and plans to roll out a similar trial in Yangon.[17] On 22 July 2015 the CEO of Telenor Myanmar announced that 55% of Telenor's 10 million mobile subscribers were data users,[18] increasing the low estimate of internet users in Myanmar to at least 5.5 million. Internet World Statistics reported in Nov 2015 that penetration was 12.6%.[19] As of 30 June 2017 Myanmar has 13,747,506 internet users, 25.1% population penetration, and 11,000,000 Facebook users.[16]

Mobile Phone Usage

With the growth of internet use in Myanmar and opening of telecommunications, the price of SIM cards is decreasing, going from "~245,000 kyats (reported as US$250) in 2013 to ~1,542 kyats (reported as US$1.50) in 2014."[20] Even though costs still are high for Myanmar, ranking 148th out of 188 of countries on the United Nations Development Programme's Human Development Index that have 66.9% of the country making less than 2,622 kyats per day ($2.00 USD),[20] Mobile Media & Communication found that "Myanmar people are willing to pay for mobiles, with over 18.1 million active SIM cards."[20]

VSAT Service Providers

With diver geography of Myanmar, having VSAT Serviders is a natural thing. While IPStar services were being delivered earlier now few of the commercial VSAT Service providers has emerged in 2016/2017. Below is the list:

- SEANET (SOUTHEASTASIANET TECHNOLOGIES Myanmar Co. Ltd) - Leading VSAT Services provide with complete suites of Services and Teleport right within Yangon.

Font Conflicts

Amid the growth of internet access across the country, ACM Computers & Society found that the Burmese-text font, Zawgyi, "may impede the digital potential of the country."[21] Zawgyi, considered the most widely-used font throughout Myanmar, is not Unicode, meaning that it does not use "an intelligent rendering engine to make sure each script element has one and only one code point."[21] This can stop websites with Zawgyi from being accessible from other countries or people using Unicode.

ACM Computers & Society also claimed that Zawgyi has difficulty typing certain ethnic languages of Myanmar, meaning that "Myanmar’s ethnic languages cannot be represented or co-exist with Burmese languages when the non-Unicode Zawgyi font is used."[21]

While Unicode began to spread through Myanmar with initiatives such as including both Zawgyi and Unicode on Android versions 4.4 and newer,[20] Lorian Leong of Mobile Media & Communication found that the lack of Unicode "influences users’ access and dependency on others to help install such services, and creates constraints and limitations to content."[20]

Blogging

An October 2010 survey found that blogging is the fastest growing type of Internet use in Myanmar, with a 25 percent increase from 2009.[22] A non-scientific survey taken in 2009 found that:[23]

- Blogs focus on entertainment (14%), technology, computers, and the Internet (17%), books and literature (9%), news (6%), hobbies and travel (6%), politics (5%), and religion (4%), among other topics;

- 52 percent of Burmese bloggers write from Burma and 48 percent write from abroad;

- 72% of bloggers are men and 27% are women;

- 77% of bloggers are single and 14% are married;

- 35 percent of bloggers are 26 to 30 years old and 29 percent are 21 to 25 years old;

- 80 percent blog in Burmese, while 8 percent blog in English, 10 percent write in both languages, and the rest use ethnic minority languages such as Kachin, Karen, and Chin.

For more information, go to the full article on Blogging in Myanmar.

Social Media

According to the Development Institute of the Russian Federation, Myanmar "still [has] social media penetration levels below 10%."[24] Despite this, internet and social media usage is still rising and influential, with Facebook usage among a variety of people in Myanmar, including farmers.[25] While social media usage spreads, people using platforms such as Facebook use it for controversially both good and bad reasons.

According to Reuters, "U.N. human rights experts investigating a possible genocide in Myanmar said [...] that Facebook had played a role in spreading hate speech there."[26] The plausible genocide with the Rohingya Muslims was found to be affected by Facebook, as Reuters found that it was "used to convey public messages but we know that the ultra-nationalist Buddhists have their own Facebooks and are really inciting a lot of violence and a lot of hatred against the Rohingya or other ethnic minorities."[26]

With the growth of social media and its capability to spread both news and opinionated information, some information managers in Myanmar are learning about the potential of social media through a workshop run by UNESCO, Myanmar Information Management Unit, and the ICT4Peace Foundation in which they discuss big data and trends.[27] According to UNESCO, the workshop "gave participants a chance to learn about social media and data trends, the platforms available, their characteristics, and how to effectively leverage these for crisis information management"[27] in addition to advising the managers about the use of social media in issues such as hate speech or election violence.[27]

Censorship

As Myanmar gradually expands its technologies and the internet access/penetration across the country, it still deals with problems regarding censorship, with Freedom House in its 2017 Myanmar country profile stating that "conditions for the media in Myanmar have improved significantly since the country began its ongoing transition from military dictatorship toward electoral democracy. However, the government maintains tight control over the media sector through the use of harsh defamation and other laws."[6] Throughout this last century after internet penetration began Myanmar, the country has been noticed for its actions regarding censorship, some of which are listed below:

- Listed as selective in the political and Internet tools areas, as substantial in social, and as no evidence of filtering in conflict/security by the OpenNet Initiative in August 2012.[28][29]

- Listed as an Internet enemy by Reporters Without Borders (RWB) in 2011.[30]

- Listed as not free for both net freedom and press freedom according to Freedom House in 2017.[6]

History

Prior to September 2011 the government used a wide range of methods to restrict Internet freedom, including legal and regulatory barriers, infrastructural and technical constraints, and coercive measures such as intimidation and lengthy prison sentences. Although the authorities lacked the capacity to pervasively enforce all restrictions, the impact of sporadic implementation and the ensuing chilling effect was profound.[31] While information circulating on the Internet is still closely monitored, reforms by the Burmese regime that began in 2011 resulted in information being more freely circulated.[30]

Internet censorship in Myanmar was classified as pervasive in the political area and as substantial in social, conflict/security, and Internet tools areas by the OpenNet Initiative in December 2010.[32] Myanmar is listed as an Internet enemy by Reporters Without Borders in 2012.[30] Myanmar's status is "Not Free" in Freedom House's Freedom on the Net 2011 report.[31] By 2014, the status had been revised to "Partly Free".[33]

Myanmar utilised a network specifically for domestic use that is separate from the rest of the Internet to limit the flow of unwanted information into and out of the country.[31]

The Internet infrastructure was also controlled through total shutdowns and temporary reductions in bandwidth.[31] During the 2007 street protests, the junta completely shut down internet connectivity from 29 September to 4 October.[34][35] And state-controlled ISPs occasionally applied bandwidth caps to prevent the sharing of video and image files, particularly during politically sensitive events, such as the November 2010 elections.[31][36]

Prior to September 2011 Myanmar banned the websites and blogs of political opposition groups, sites relating to human rights, and organisations promoting democracy.[32] The term "Myanmar Wide Web (MWW)" is a pejorative name for the portion of the World Wide Web that is accessible from Myanmar.[37] Many sites containing keywords or phrases that were considered suspicious, such as "Burma", "drugs", "military government", "democracy", "student movement", "8888" (a reference to the protest movement that began on 8 August 1988), and "human rights" were blocked and a few still are.[38][31] Access to Yahoo! Mail, MSN Mail, Gmail, the video-sharing site YouTube, the messaging feature of the social-networking site Facebook, Google’s Blogspot, and the microblogging service Twitter were sporadically blocked.[31] However, Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) systems including Skype were and are available. Fortinet, a California-based company, provides the government with software that limits the material citizens can access on-line, especially e-mail service providers and pornographic websites.[39][40]

Once the leadership power of the country transferred to the National League for Democracy (NLD) and Aung San Suu Kyi in 2016, the speed of the internet stayed generally stagnant with slight improvements in regard to more phone shops and WiFi in bigger cities,[41] but the freedom of internet use slowed down.[6] A few years prior, in 2013, the Telecommunications Law included legislation that was seen as restrictive to free speech,[6] as seen through the incarceration of 38 people charged with violating the Telecommunications Law through online defamation since the NLD came to power.[42] Ever since its enactment in 2013, people have stated that the law is being used to silence anyone that speaks badly of the government,[42] making freedom of speech on the internet difficult. According to Freedom House, the tense environment with the Rohingya refugee crisis starting in 2015 in the Rakhine state has thus created more concern for the future of freedom of speech online.[6] Once Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD came into power in 2016, it was supposed that 17 journalists were incarcerated under the Telecommunications Law.[43] Despite restrictions, the number of Internet users in Myanmar continues to grow, albeit having a low bandwidth and slow connections.[6] According to World Bank, "mobile and internet penetration has increased significantly from less than 20% and 10% in 2014, to 60% and 25% respectively" as of October 2017.[44]

Many political prisoners in Myanmar were charged under the laws mentioned above.[31] However, in the second half of 2011 as part of a larger series of amnesties the military regime released a number of journalists and bloggers.[30] For example:

- Reporters Without Borders counted at least 15 journalists and three internet activists in detention in 2011;[45]

- Nay Phone Latt, a blogger and owner of three cybercafes, was released in January 2012 after being sentenced to 20 years and six months in prison in November 2008 for posting a cartoon of General Than Shwe, Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council from 1992 to 2011;[46]

- Members of the 88 Generation Students Group, Htay Kywe, Min Ko Naing, Ko Jimmy, Nilar Thein, Mie Mie, and nine others, were convicted on 11 November 2008 of four counts of "illegally using electronic media" and one count of "forming an illegal organization" and sentenced to 65 years in prison apiece, while the group's photographer, Zaw Htet Ko Ko, and other members were given sentences ranging from three to eleven years;[47][48] Min Ko Naing has since been released. Other members of the group were released on 13 January 2012, as part of a mass presidential pardon for political activists.[49]

- Freelance reporter Hla Hla Win was released in 2011 after being arrested in September 2009 and given a 27-year prison term, including 20 years for violating the Electronic Transactions Law. Her associate, Myint Naing, arrested at the same time was also released after receiving a 32-year sentence;[50]

- Blogger Win Zaw Naing was released in January 2012 after being arrested in November 2009 and facing up to 15 years in prison for posting pictures and reports about the September 2007 protests;[51][52]

- A former military officer and a foreign affairs official were sentenced to death in 2010, and another foreign affairs official was sentenced to 15 years in prison, for leaking information and photographs about military tunnels and a general’s trip to North Korea, there are conflicting reports that the death sentences were reduced to life or to 32 years in 2012;[53][54][55]

- Journalist Ngwe Soe Lin was released in late 2011 after being arrested at a cybercafe in Yangon, was sentenced to 13 years in prison in January 2010 for working for an exile media outlet;[56]

- Activist Than Myint Aung was released in January 2012 after receiving a 10-year prison sentence in July 2010 for violating the Electronic Transactions Law by using the Internet to disseminate information that was "detrimental to the security of the state";[57][58] and

- Photographer Sithu Zeya was granted a conditional release after being sentenced to eight years in prison in December 2010 for taking pictures in the aftermath of an April 2010 bomb blast in Yangon and for his affiliation with an exiled media outlet.[59]

Recent reforms

Following decades of military rule, Burma has undergone a series of significant political and economic reforms since elections in November 2010. March 2011 saw the end of formal military rule in the country, with reformist Thein Sein becoming the country’s first civilian president in half a century. While by-elections held in April 2012 included numerous reports of fraud, the opposition National League for Democracy, including leader and Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, won seats after contesting their first elections since 1991. In 2011-2012 hundreds of political prisoners were released and legislative changes re-establishing labour rights in the country.[38]

Reforms have also extended to the country’s strict information control regime. Beginning in September 2011, the historically pervasive levels of Internet censorship were significantly reduced. International news sites, including Voice of America, BBC, and Radio Free Asia, long blocked by Burmese censors, had become accessible overnight. A number of previously censored independent Burma-focused news sites which had been highly critical of Burma’s ruling regime, such as the Democratic Voice of Burma and Irrawaddy, were suddenly accessible. Following the reduction in online censorship, the head of Burma’s press censorship department described such censorship as "not in harmony with democratic practices" and a practice that "should be abolished in the near future."[38]

In August 2012, the Burmese Press Scrutiny and Registration Department announced that all pre-publication censorship of the press was to be discontinued, such that articles dealing with religion and politics would no longer require review by the government before publication. Restrictions on content deemed harmful to state security, however, remained in place. Pornography was still widely blocked, as were content relatings to alcohol and drugs, gambling websites, online dating sites, sex education, gay and lesbian content, and web censorship circumvention tools. In 2012 almost all of the previously blocked websites of opposition political parties, critical political content, and independent news sites were accessible, with only 5 of 541 tested URLs categorised as political content blocked.[38]

In a September 2012 speech to the United Nations General Assembly, Burmese President Thein Sein described the country as having taken "irreversible steps" towards democracy, a speech broadcast on state television for the first time.[38]

As significant as they are, the impact of these reforms may be less than expected considering only 0.3 percent of Burma's population has Web access, outside of Burma's largest city, Yangon, few can read English.[60]

Laws

Laws regulating the Internet include the Computer Science Development Law (1996), the Wide Area Network Order (2002), and the Electronic Transactions Law (2004), while the Printers and Publishers Registration Act (1962) regulates the media.[61] These laws and associated regulations are broadly worded and open to arbitrary or selective interpretation and enforcement. The Electronic Transactions Law covers "any act detrimental to"—and specifically "receiving or sending and distributing any information relating to"—state security, law and order, community peace and tranquility, national solidarity, the national economy, or national culture. Violators face fines and prison terms of 7 to 15 years.[62] The importing and use of a modem without official permission is banned, with penalties for violations of up to 15 years in prison.[63] Harsh prison terms and selective enforcement encourages self-censorship. However, expression in online environments such as comment features where posters can remain anonymous remains relatively free.

These laws are still in place, and authorities had promised to adopt a media law that will put an end to censorship back in 2012 in addition to revising or repealing the Electronic Act and emergency rule.[30] In January 2013, the new media law was not in place and there was some concern that the country could backslide and return to the repressive tendencies of the past,[64] which ended up happening later on in the year with the 2013 Telecommunications Law, which has been considered a breach of freedom of speech online.[6] While the government of Myanmar amended the 2013 law slightly in August 2017, including an amendment that "permits judges to release people on bail, allows only those directly affected, or with permission from those directly affected, by the offense to press charges, and reduces the maximum prison sentence to two years”[65] for crimes under article 66 of the law, the government did not change anything about article 66(d), which is considered a "highly controversial clause that restricts freedom of speech."[43]

Censorship circumvention

The use of Internet censorship circumvention methods was officially banned by the military government; the Myanmar ISPs blocked many bypass and proxy websites, but were unable to block all circumvention methods. With the removal of blocking of web sites after 2012, the need for proxies was reduced and therefore the need to block them was also removed. Cybercafes were required by law to keep records on their customers’ activities and provide police access to the records upon request. However, many cafes do not systematically enforce such monitoring, often assisting their users in circumventing censorship instead. In response the government increased surprise inspections of cybercafes, cafes posted signs warning users not to visit certain websites. Licensing law instructed cybercafes to install CCTV cameras and assign at least four security staff to monitor users.[31]

See also

- Human rights in Burma

- Media in Burma

- Digital divide in Myanmar

References

- Martin, Steven; et al. (2002). Myanmar (Burma), 8th Ed. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 978-1-74059-190-4.

- "Internet Services Tariff", Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications, Information Technology department, Ministry of Communications, Posts and Telegraphs, accessed 10 June 2011 Archived 20 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Internet Cafe in Myanmar", Today in Myanmar, 13 February 2009

- "Two Telecoms Race To Wire Myanmar". Forbes. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- "Myanmar Internet Usage and Telecommunications Reports". www.internetworldstats.com. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- "Myanmar". freedomhouse.org. 14 November 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Country Code List: ISO 3166-1993 (E)". American National Standards Institute, Inc. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- "Company at a glance" Archived 16 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Yatanarpon Teleport Co., Ltd.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Myanmar Speednet".

- "Myanmar Internet Provider" Archived 10 September 2012 at Archive.today, Guide for Myanmar 2007

- s-down.html "Internet service hampered as Myanmar Teleport server breaks down", Mizzima News Agency, 10 February 2009

- "No More Proxies: Myanmar Teleport", Saw Yan Naing, The Irrawaddy Publishing Group, 29 May 2008

- "Bypassing Internet Censorship in Burma / Myanmar", VPNHero.com, 16 March 2011

- "Google Public Data: Burma Internet penetration". Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Asia", Internet World Stats, 23 September 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Wai-Yan Phyo Oo and Saw Pyayzon (30 July 2010). "State of Internet Usage in Myanmar". Bi-Weekly Eleven (in Burmese). 3 (18): 1–2.

- ""Competition, watch out' says Telenor Myanmar CEO, as subs over 10 million".

- http://www.internetworldstats.com/asia.htm#mm, Internet World Stats, 15 November 2015.

- Leong, Lorian (1 February 2017). "Mobile Myanmar: The development of a mobile app culture in Yangon". Mobile Media & Communication. 5 (2): 139–160. doi:10.1177/2050157917689950.

- Liao, Han-Teng (13 January 2017). "Encoding for access: how Zawgyi success impedes full participation in digital Myanmar". ACM SIGCAS Computers and Society. 46 (4): 18–24. doi:10.1145/3040489.3040493. ISSN 0095-2737.

- "Blogging Increases 25% Within A Year" (Blog Yay Thar Hmu Ta Nhit Ah Twin 25 Yar Khaing Hnoan Toe Lar), Myanmar Internet Journal, 17 December 2010

- “Myanmar Blogger Survey 2009”, Nyi Lynn Seck, Myanmar Blogger Society, Rangoon, slides, 2 February 2010

- "The State of Social Media and Messaging in Asia Pacific: Trends and Statistics" (PDF). Development Institute of the Russian Federation.

- Mod, Craig. "The Facebook-Loving Farmers of Myanmar". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Miles, Tom. "U.N. investigators cite Facebook role in Myanmar crisis". U.S. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- "Myanmar information managers learn about social media, big data and the crisis response". UNESCO. 31 October 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- OpenNet Initiative "Summarized global Internet filtering data spreadsheet", 29 October 2012 and "Country Profiles", the OpenNet Initiative is a collaborative partnership of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto; the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University; and the SecDev Group, Ottawa

- "ONI Country Profile: Burma", OpenNet Initiative, 6 August 2012

- Internet Enemies Archived 23 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders (Paris), 12 March 2012

- "Burma Country Report", Freedom on the Net 2011, Freedom House, 18 April 2011

- "ONI Country Profile: Burma", OpenNet Initiative, 22 December 2010

- "Freedom on the net 2014" (PDF).

- "Myanmar's main Internet link not working: official", Asia Pacific Nets, channelnewsasia.com, 28 September 2007

- Burma "Junta tightens media screw", Michael Dobie, BBC News, 28 September 2007

- "Pulling the Plug: A Technical Review of the Internet Shutdown in Burma", Stephanie Wang and Shishir Nagaraja, OpenNet Initiative, 22 October 2007

- Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering, Ronald Deibert (ed), MIT Press, 2008, p.340, ISBN 9780262042451

- "Update on information controls in Burma", Irene Poetranto, OpenNet Initiative, 23 October 2012

- "Internet Filtering in Burma in 2005: A Country Study". Open Net Initiative.

- "Burma bans Google and g-mail". Burma Net News. 27 June 2006. Archived from the original on 6 July 2006. Retrieved 28 June 2006.

- Calderaro, Andrea. (2014). Digitalizing Myanmar: Connectivity Developments in Political Transitions. Internet Policy Observatory. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/internetpolicyobservatory/6

- Roewer, Richard (2017). "Myanmar's National League for Democracy at a Crossroads". GIGA Focus Asien (1).

- "Burma: Telecom Law Amended but Key Defamation Provision Remains Unchanged | Global Legal Monitor". www.loc.gov. Zeldin, Wendy. 6 September 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Press Freedom Barometer 2011: Burma" Archived 26 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders

- "Burma blogger jailed for 20 years", BBC News, 11 November 2008

- Saw Yan Naing (11 November 2008). "40 Burmese Dissidents Given Prison Terms of up to 65 Years". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- Jonathan Head (11 November 2008). "Harsh sentences for Burma rebels". BBC News. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- "High-profile dissidents freed in Burma amnesty". BBC News. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Appeal case for DVB reporter Hla Hla Win", Myint Maung, Mizzima News, 24 March 2010

- "Freedom on the Net 2012 - Burma", Freedom House, 25 September 2012

- "Another blogger arrested for posts about Saffron Revolution", International Freedom of Expression Exchange, 18 November 2009

- "Two Receive Death Sentence for Information Leak", Irrawaddy Publishing Group, 7 January 2010

- "Political Prisoner Profile: Win Naing Kyaw", Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma), accessed 2 February 2013

- "Political Prisoners List", Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma), 8 January 2013

- "Another Video Reporter Gets Long Jail Sentence", Reporters Without Borders, news release, 29 January 2010

- "Court Extends Prison Sentence of NLD Liberated Area Member", Myint Maung, Mizzima News, 16 July 2010

- "BURMA: Prisoners released and others still detained", Asian Human Rights Commission, 3 February 2012

- "Photographer Sentenced to Eight Years in Prison", Reporters Without Borders, news release, 28 December 2010

- "YouTube, BBC ban lifted in Burma", Patrick Winn, The Rice Bowl, the GlobalPost's reported blog on Asia, 16 September 2011

- "Myanmar Law (1988–2004)", Burma Lawyers’ Council

- "The Electronic Transactions Law (The State Peace and Development Council Law No. 5/2004)", Myanmar Law (2004), Burma Lawyers' Council, 30 April 2004

- Internet Enemies: Burma Archived 30 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Reporters Without Borders, Paris, 12 March 2009

- "Call for ‘Concrete’ Media Reforms", Radio Free Asia, 16 January 2013

- Naing, Shoon. "Myanmar retains tough clause in communications law despite calls..." U.S. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

External links

- "The Internet and Burma (1998-2009)", Mizzima News, 24 September 2009

- "Burning down Myanmar's Internet firewall" an article on Myanmar's Internet Censorship by Shawn W Crispin in Asia Times Online, 21 September 2007

- Internet in Mawlamyine

- Internet In Myanmar a website listing the different Internet Service Providers in Myanmar and comparing their plans and respective coverage