Isaac Cruikshank

Isaac Cruikshank (1764–1811), Scottish painter and caricaturist, was born in Edinburgh and spent most of his career in London. Cruikshank is known for his social and political satire. [1] His sons Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856) and George Cruikshank (1792–1878) also became artists, and the latter in particular achieved fame as an illustrator and caricaturist.

Isaac Cruikshank | |

|---|---|

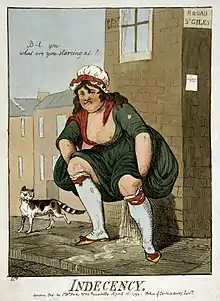

Indecency, among Cruikshank's most notable works.

Published in London by S.W. Fores, 1799 | |

| Born | 1764 |

| Died | 1811 |

| Cause of death | alcohol poisoning |

| Nationality | Scot |

| Occupation | artist, caricaturist |

| Spouse(s) | Mary MacNaughton (1769–1853) |

| Children | Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856) George Cruikshank (1792–1878) Margaret Eliza (1808–1825) Mary (1795–1795) |

| Parent(s) | Elizabeth Davidson (born c.1725) Andrew Crookshanks (c.1725–c.1783) |

Biography

Isaac Cruikshank was born in 1764 to Elizabeth Davidson (born c.1725), daughter of a gardener, and Andrew Crookshanks (c.1725–c.1783), a former customs inspector,[1] dispossessed for his role in the Jacobite rising of 1745. Isaac grew up in New North Kirk parish in Edinburgh after his family moved there. He was the youngest child, and was interested in all sorts of hobbies including sports and music. Isaac studied with a local artist, possibly John Kay (1742–1826).

In 1783 Cruikshank left Scotland to travel to London with his master.[1] There he married Mary MacNaughton (1769–1853) on 14 August 1788.[2] The couple had five known children, two of whom died in infancy. A daughter, Margaret Eliza (1808–1825),[3] a promising artist, died at the age of eighteen of tuberculosis. Their sons Isaac Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856)[4] and George Cruikshank (1792–1878)[5] also became artists.[6]

The Friends of the People, 15 November 1792, caricaturing Joseph Priestley and Thomas Paine, (Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum).

The Friends of the People, 15 November 1792, caricaturing Joseph Priestley and Thomas Paine, (Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum).

Cruikshank's first known publications were etchings of Edinburgh "types", from 1784. His first caricature etching called Scotch Eloquence was of Edinburgh characters.[7] He produced illustrations for books about the theatre, did the frontispiece for Witticisms and Jests of Dr Johnson (1791), and illustrated George Shaw's extensive General Zoology (1800–26). [1]His water colours were exhibited, but in order to make a living, he found it more lucrative to produce prints and caricatures. He was responsive to the marketplace but firm in his dislikes of Napoleon and Britain's home-grown political radicals, including, for example, the members of the London Corresponding Society and the Society of the Friends of the People. He and James Gillray developed the figure of John Bull, the nationalistic representation of a solid British yeoman. His Olympic games or John Bull introducing his new ambassador to the grand consul (1803) and Boney at Brussells (also 1803) contrast an implied European capitulation and British defiance under the threat of invasion.[8]

Near the start of his fame in 1789, Cruikshank produced several watercolours adapted from his earlier drawings, and was on exhibition at the Royal Academy. Publisher John Roach was a friend and patron. Cruikshank later also worked with print dealer S. W. Fores and Johnny Fairburn. He also collaborated with G. M. Woodward, and later, with his son George. (See also G.S. Tregear.) He also etched and designed lottery tickets and the song-heads of musical scores.[9]

Cruikshank died of alcohol poisoning at the age of fifty-five as a result of a drinking contest, of which he was declared the winner.[1] He is buried near his home in London.[6]

Caricature Prominence During Isaac Cruikshank's Era

During the late 18th century, there was an enormous amount of propaganda due to political turbulence in Europe, in particular the French Revolution. The British Monarchy was also being highly criticized for debauchery during this time, as it was also a period of economic hardship and debt. Political caricature and graphic satire became a prominent outlet for mass propaganda to express competing perspectives on political and economic issues. The revolution also triggered feelings and expressions of patriotism towards artists' home countries which they depicted by shedding a grotesque light on their countries' enemies.[10]

Isaac Cruikshank, James Gillray, and Thomas Rowlandson were considered the leading caricaturists during this period, and they produced many popular sketches and graphics satirizing contemporary issues. These three prominent artists' distinct styles and subject matter became notable and widespread throughout Europe, although they also adapted and borrowed images from lesser-known artists. The three illustrators were sometimes considered rivals as their ideas often took opposing positions on important matters, despite sometimes collaborating on works. A common theme in all three artists' works was the portrayal of gluttony and cannibalism meant to represent the exploitation of the people by the monarchy, sparked by the effects on the economy of France of the Revolution.[7] Their work, however, had to be published exclusively in Britain, as in France censorship laws were at an all-time high.[11]

In 1803 after the French declared war on Britain, numerous patriotic prints resulted focused around support and strength for the British homefront. Cruikshank was one of the first to illustrate Napoleon as a negative caricature in his work Buonaparte at Rome Giving Audience in State (1797).[12] In 1809, Cruikshank created French Generals Receiving an English Charge which largely attacked Prince Frederick, Duke of York for his scandalous affairs with Mary Anne Clarke during the time.[13]

Legacy

A contemporary of James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, Cruikshank was part of what has been called "the Golden Age of British Caricature." Some have called his work "uneven"[14] but at its best, it provided a vivid insight into the cultural and political preoccupations of the British during the decades at the turn of the nineteenth century. He was an avid and skilled water colourist, and had a "keen sense of humour", although his achievements during his shortened life suffered from the greater successes and "more prolonged career of his gifted son."[15]

There are believed to be at least 345 prints created by Isaac Cruikshank between 1793 and 1800 that are in the British Museum's collection. E.B. Crumbier created a catalogue of around 1350 images that Cruikshank produced in his lifetime.[7] In the Huntington Library, California, there is also a collection of his watercolour drawings.

Cruikshank, like his son Isaac Robert Cruikshank and more famous son George Cruikshank, was a pioneer in the history of comics through creating several cartoons which make use of narrative sequences and/or speech balloons. [1]

Gallery

The Abolition of the Slave Trade (1792), Cruikshank's depiction of the alleged murder of a slave girl by John Kimber, published April 10, 1792

The Abolition of the Slave Trade (1792), Cruikshank's depiction of the alleged murder of a slave girl by John Kimber, published April 10, 1792 The Friends of the People, 15 November 1792, caricaturing Joseph Priestley and Thomas Paine, (Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum).

The Friends of the People, 15 November 1792, caricaturing Joseph Priestley and Thomas Paine, (Chemical Heritage Foundation Museum). Isaac Cruikshank, Debating Society (Substitute for Hair Powder). London: Published by Laurie & Whittle, 5 May 1795. A reference to William Pitt the Younger's new tax on hair powder.

Isaac Cruikshank, Debating Society (Substitute for Hair Powder). London: Published by Laurie & Whittle, 5 May 1795. A reference to William Pitt the Younger's new tax on hair powder. "The Humours of Belvoir Castle -- or the Morning After", a March 1, 1799 English caricature engraving showing the aftermath of a night of upper-class debauchery at a large country mansion, marking the celebration of the owner's coming of age.

"The Humours of Belvoir Castle -- or the Morning After", a March 1, 1799 English caricature engraving showing the aftermath of a night of upper-class debauchery at a large country mansion, marking the celebration of the owner's coming of age.

Notes

- "Isaac Cruikshank". lambiek.net.

- Ancestry.com. England, Select Marriages, 1538–1973 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. (subscription required)

- Ancestry.com. London, England, Deaths and Burials, 1813–1980 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010., p76/js2/026. (subscription required)

- Ancestry.com. England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. (subscription required)

- London Metropolitan Archives, St George, Bloomsbury, Register of baptisms, Oct 1775-Nov 1808, P82/GEO1/002. (subscription required)

- Alexander Meyrick Broadley, Napoleon in Caricature, 1795–1821, John Lane, 1911, pp. 29–30

- "Oxford DNB article: Cruikshank, Isaac". www.oxforddnb.com. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- Napoleonic and Georgian Social and Political Satire', Thursday 25 June 2015, Bloomsbury Auctions, London, 2015.

- Broadley, p.26.

- Boime, Albert (1992). The Sketch and Caricature as Metaphors for the French Revolution. Deutscher Kunstverlag GmbH Munchen Berlin.

- Goldstein, Robert Justin (1 January 1989). Censorship of Political Caricature in Nineteenth-century France. Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873383967.

- Morris, Marilyn. The British Monarchy and the French Revolution.

- "Isaac Cruikshank". www.oxforddnb.com. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Robert L. Patten, "Cruikshank , Isaac (1764–1811)," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. (Oxford: OUP, 2004. 11 May 2007.)

- Broadley, 26.

- Broadley, p. lxxii.

Electronic resources

- Cruikshank's work at the National Portrait Gallery

- Isaac Cruikshank at Artcyclopedia

- Isaac Cruikshank - Cartoons

- Connected Histories: British History Sources, 1500-1900 This Jisc-funded web service provides federated searching of online historical resources for research. The web link provides access to primary sources which refer to Isaac Cruikshank.

Resources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isaac Cruikshank. |

- The British Museum, the Huntington Library in California, and The Houghton Library at Harvard University all have significant holdings of Cruikshank's work.

- George, Mary Dorothy. Hogarth to Cruikshank: Social Change in Graphic Satire. 1967.

- Nygren, Edward J., ed. Isaac Cruikshank and the Politics of Parody: Watercolors in the Huntington Collection. University of California Press, 2005. ISBN 0-87328-147-0; ISBN 978-0-87328-147-8

- Patten, Robert L.. "Cruikshank , Isaac (1764–1811)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. 11 May 2007.