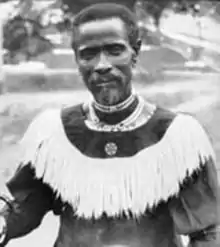

Isaiah Shembe

Isaiah Mloyiswa Mdliwamafa Shembe (c. 1865[1][2] – 2 May 1935), was the founder of the Ibandla lamaNazaretha, South Africa, which was the largest African-initiated church in Africa during his lifetime.[3] Shembe started his religious career as an itinerant evangelist and faith healer in 1910. Within ten years, he had built up a large following in Natal with dozens of congregations across the province. The Shembe Church eventually had well over one million members before it began to splinter into competing groups in the 1980s.

Isaiah Shembe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 3, 1865 Ntabamhlophe (Estcourt Area), South Africa |

| Died | May 2, 1935 (aged 70) KwaZulu Natal |

| Education | None |

| Employer | Shembe Church |

| Known for | Founder of the Shembe church |

| Title | INkosi yaseKuphakameni |

Birth and early life

He was born in 1865, at Ntabamhlophe (Estcourt Area), in the Drakensberg region of Natal. He had pure Zulu descent. When he was very young, his family had fled from Shaka during the Mfecane period. His father, Mayekisa, traced his lineage four generations back among members of the Ntungwa tribe.[4]:2–3 His mother Sitheya, the daughter of Malindi Hadebe, was born at Mtimkulu.[2]:1

Shembe's family left Natal for the adjacent Harrismith district of the Orange Free State in the 1880s, ending up there as tenants for an Afrikaner family named the Graabes.[5] The young Shembe appears to have laboured for this Boer family as well, and spent considerable time working with the farm's horses. There is a considerable lore of hagiographic tradition concerned with the young Shembe. It was alleged he died and was resurrected at the age of three when relatives sacrificed a bull before his body could be interred. He was also allegedly visited by God on many occasions during these years.[2]:2–7[4]:7–22

Shembe claimed that the voice of God taught him how to pray. Thereafter it commanded him to find a place to pray to God on regularly basis. He started visiting the Wesleyan Church that was nearby. However he did not spend much time there, because the laws which he was taught in vision by the Word, were not followed in the church. For example, baptism by immersion was not practised, this was one of the key laws that made him desert the church. By the time of the South African War, Shembe was married and was working for the Graabes as a tenant in his own right. However, the war disrupted his situation. After abandoning his wives, he spent some time on the Rand as a migrant.[5]:18 During this time, he met the African Native Baptist Church (in Boksburg) which was led by Reverend William Leshega, who later baptized him on 22 July 1906.

Early years as an evangelist

Between 1906 and 1910, Shembe was a minor evangelist in Leshega's church. The latter visited him in Harrismith in 1906 and baptized him there (by immersion). For the following two years he worked as an itinerant evangelist, and was then given an official preacher's certificate by Leshega in 1908. It appeared that Shembe then led a congregation for Leshega in Witzieshoek until 1909, when Leshega affiliated with John G. Lake's Apostolic Faith Mission.[6]:77–8

Shembe claimed that the Word ordered him to leave his wives and family and go to Natal. Initially he resisted separating from his wives; nine of his children died after that resistance. This was followed by him being struck by lightning after ascending a mountaintop. The lightning strike injured his thigh and he took two weeks to recover. Eventually, he agreed to follow the word to Natal. He arrived in Durban on 10 March 1910.[7] Messengers preceded his arrival into various parts of Natal, proclaiming that "A Man of Heaven" had been sent by God to preach to the African people.

Leader of the Church of Nazareth, 1910–1935

By all accounts, Shembe had an electric effect and was able to rapidly build congregations in a number of areas. He formed the Ibandla lamaNazaretha in 1910, with his converts consisting primarily of poverty-stricken migrants living at the margins of Natal's urban areas. In 1911, he purchased a freehold farm and established a holy city at eKuphakameni that sought in part to keep his people on the land free of white control. He also established a yearly pilgrimage to the Holy Mountain of Nhlangakazi, an event that was central to the Nazarites.[8] As his following grew and he could not provide land for everyone, Shembe began training his followers to be exemplary workers. His exhortation and strict religious regimens turned his followers into a distinctive group known for their honesty, punctuality, and work ethic.

In addition to his preaching and healing, Shembe was known for composing numerous Zulu hymns and sacred dances, for creating sacred costumes that combined Zulu and European clothing styles, for developing a new liturgical calendar (that omitted Christmas, Easter, and Sunday worshipping), and for dietary laws that included a restriction against eating chicken, pork and other unclean foods as found in the Old Testament of the Bible.[9] He advocated worship on the biblical Sabbath, rather than on Sunday. He chose to identify instead with the Sabbath of God, Jehovah. He saw the Sabbath as essential to the wholeness and well-being of Africans.

In the 1930s, Shembe (who was an autodidact in terms of literacy and theology) commissioned his neighbour, John Dube, to write his biography. This book, uShembe, appeared shortly after its subject's death.[2] This biography contains much of the essential Shembe lore and hagiography. Because Dube was an ordained minister and not a Nazarite, he does not always present Shembe in flattering terms. His bona fides as a prophet are questioned, while his ability to extract financial contributions from his membership is highlighted.[2]:89–92 Shembe's followers, though, wrote down many of his teachings. As a result, the Nazarite church has an extensive written theological corpus, perhaps the largest of any African-initiated church.

Shembe's legacy has created some controversy. In a 1967 book, G.C. Oosthuizen argued that the movement was "a new religion that sees Isaiah Shembe as 'the manifestation of God.'" Oosthuizen was attacked by Bengt Sundkler and Absolom Vilakazi as being too westernized to understand Zulu culture, and claimed that the movement remained Christian. However, Oosthuizen's view has been embraced by two of Shembe's successors, his younger son Amos Shembe and his grandson Londa Shembe, who (although they fought with each other over who was the legitimate successor and eventually formed two separate branches of the church), both of whom believe that Shembe did indeed create something new.

Today, it is evident enough that the view of Oosthuizen was correct, since Ibandla lamaNazaretha is no longer recognized as a church which affiliates under Christianity; rather it is an independent religion, the religion of AmaNazaretha.

References

- Absolom Vilakazi; Bongani Mthethwa; Mthembeni MpanzaJ (1986). Shembe: The Revitalization of African Society. Johannesburg: Skotaville. ISBN 978-0-94700-908-3.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- John Langalibalele Dube (1936) uShembe (in Zulu) (Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter Publishers Pty Ltd)

- University of Calgary

- I. Hexham, G. Oosthuizen, eds. (1996) The Story of Isaiah Shembe, Vol. 1, History and Traditions Centered on Ekuphakameni and Mount Nhlangankazi (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen)

- L. Gunner (2002) The Man of Heaven and the Beautiful Ones of God (Leiden: Brill) ISBN 9004125426

- B. Morton (2014). "Shembe and the Early Zionists: A Reappraisal". New Contree. 69.

- I. Hexham, ed. (1994) The Story of Isaiah Shembe Volume II: The Scriptures of the amaNazaretha of EKuphakameni, p. 82. Trans by L. Shembe and H-J. Becken. (Calgary, University of Calgary Press)

- J. Cabrita (2014) Text and Authority in the South African Nazaretha Church (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

- Irving Hexham (2001). "The amaNazaretha". In Stephen D. Glazier (ed.). Encyclopedia of African and African-American Religions. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41592-245-6.

Bibliography

- H.L. Pretorius (1995) Historiography and historical sources regarding African indigenous churches, Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston

- Oosthuizen, G.C., ed. (1986) Religion Alive: Studies in New Movements and Indigenous Churches in Southern Africa, Hodder and Stoughton, Johannesburg