Jane the Runaway, Bridge Town

Jane from Bridge Town, (late eighteenth-century), was an urban slave in Barbados under the ownership of John Wright. Jane's life illustrates a bigger picture regarding slavery and violence in the early eighteenth century. Jane was captured in West Africa and brought over through the Middle Passage to Barbados. She was described by her markings in her runaway ad which made Jane’s body seem vulnerable.

The exact date of Jane’s self-liberation from her owner is unsure but we are able to assume it was a few days prior to January 13, 1789[1] when Jane's master, John Wright, had sent in a runaway advertisement for Jane in the Barbados Mercury. John Wright offered a 20 shilling[1] reward for the person who would return Jane to him.

Country Marks vs Enslaved punishment marks

Marisa J. Fuentes[1] discusses the life of Jane in her first chapter of her book."Left only with the newspaper trace of her scarred body, we lose her alongside 'all the lives that are outside of history.'"[1]

"Jan. 13, 1789 "RUNAWAY: A short black skin negro women named JANE, speaks broken English, has her country marks in [sic] her forehead and a fire brand on one of her breasts, likewise a large mark of her country behind her shoulder almost to the small of her back, and a [stab] of a knife in her neck. Whoever will bring said negro to the subscriber in Bridge Town shall receive 20 shillings... John Wright." -Barbados Mercury.[1]

The ad was intended to make the public aware of an enslaved woman who ran away so that she would be returned to her owners. Fuentes discusses the scars that were inflicted on enslaved people’s bodies to show who they belonged to.[1] Jane’s scars included a mark on her forehead, a firebrand on her breast, on her shoulder, as well as a stab of a knife on her neck.[2] Some of these marks would be a constant reminder of “pain and unfreedom;” historians believe Jane's "country marks" on her forehead and a few other places on her body were ritual marks or scars given to her in Africa.[3] The rest of the marks inflicted on Jane were punishment scars, showing a key fact of ownership: someone is able to abuse you.

Enslaved Sexual Vulnerability

Enslaved women were subjected to the power and control of their owners in multiple spaces, such as work and living spaces.[1] These enslaved women were vulnerable to any kind of treatment from the privileged white men in the household or even within the community. The primary work of the enslaved women in Barbados was agricultural labor on sugar cane plantations but some enslaved women also did domestic work inside the homes of the British colonists, especially in cities like Bridge Town.[4] Domestic work for an enslaved woman included cooking, cleaning, as well as sewing. This kind of work could mean sexual danger for these urban women since they were so close to the colonists that could possibly inflict violence.[5]

As a runaway in Bridge Town, Jane could have possibly experienced the fear of being a woman alone in the town surrounded by white and Black free men. Rape was a constant fear for the enslaved black women. Enslaved women were not able to resist sexual assaults on their bodies.[6] Jane could have possibly experienced these same fears as a runaway slave in Bridge Town. There was no easy direct way off the island so Jane would have had to survive concealed in the busy midst of the town.

Being generally vulnerable to sexual relations, enslaved women in Barbados might conceive of a pregnancy. Any children bore from the maternal side of an enslaved would result in the offspring being enslaved as well.[7] This exploitation of the enslaved women's bodies was a statement that their bodies and anything that came from them was owned and enslaved.

The control of an enslaved women's body was also profit and more control for the slave owners. Pregnancy generally made it more difficult for enslaved women to escape. Sometimes slave owners tried to get their female slaves pregnant, as it was a profit to the owners.[8] This exploitation of an enslaved women's bodies with forced sex, reminded these Black women that they had no control, not even over their own bodies or reproductive system.[9]

Concubinage and Sexual Exploitation

Bridge Town, Barbados in the late eighteenth century was a busy trade port for the island. The free Black population in Bridge Town was small but eventually grew. Even though some Black men and women were free from slavery, there was still no escape from the social, political, and economic oppression.[1] Fuentes believes that Jane would have run to Bridge Town to look for work to blend in with the rest of the community. Most of the work opportunities for the free Black women were small trades, domestic work in homes, store keeping, and prostitution.

The main occupation for enslaved women was prostitution. Slave owners could profit from enslaved women bodies not only by encouraging pregnancy, but also by selling sexual access to white men, violating these women's bodies.

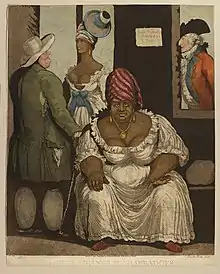

Rachael Pringle Polgreen was a freed, elite, Black woman in Bridge Town, Barbados in the late eighteenth century. Polgreen owned slaves and a brothel to sustain herself economically. She was well known all over Bridge Town to the newspaper, the Royal Navy, to white elites, as well as to other freed black elites in the community.[1]

Polgreen's brothel was to serve the sexual desires of those willing to pay for the services. Polgreen's enslaved women were available and disposable in the sexual labor. This forced "hiring-out" of enslaved women's bodies made them vulnerable to violence and reinforced their status as sexual objects.[1]

Historian Fuentes is unsure of the ultimate fate of Jane and whether she might have experienced these violent action by the British colonists and the Royal Navy. Fuentes hypothesizes that Jane possibly experienced this sexual abuse at some point or another.[1] Jane's story and life is a part of the bigger picture of the inflicted sexual and physical violence done to the enslaved women of Barbados.

References

- Fuentes, Marisa (2016). Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, And The Archive. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8122-4822-7.

- Smallwood, Stephanie E. (2008). Saltwater slavery : a middle passage from Africa to American diaspora. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04377-0. OCLC 436298967.

- Morgan, Lynda; Gomez, Michael A. (December 1999). "Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South". African Studies Review. 42 (3): 163. doi:10.2307/525256. ISSN 0002-0206. JSTOR 525256.

- "Inside the Travel Lab - Freedom & Slavery in Barbados. It's Not Black & White". Inside the Travel Lab. 2013-02-03. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- Morgan, Jennifer L. (Jennifer Lyle) (2004). Laboring women : reproduction and gender in New World slavery. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-8122-3778-1. OCLC 53485319.

- Block, Sharon, 1968-. Rape and sexual power in early America. Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture. Chapel Hill [North Carolina]. ISBN 978-1-4696-0097-0. OCLC 654308329.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Turner, Sasha. (2017). Contested Bodies : Pregnancy, Childrearing, and Slavery in Jamaica. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8122-9405-7. OCLC 987086648.

- Warren, W. A. (2007-03-01). ""The Cause of Her Grief": The Rape of a Slave in Early New England". Journal of American History. 93 (4): 1031–1049. doi:10.2307/25094595. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 25094595.

- Eaves, Shannon University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Graduate School Williams, Heather Andrea DuVal, Kathleen Glymph, Thavolia Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd Sweet, John Wood Eaves, Shannon. "A Sad Epoch in the Life of a Slave Girl": The Sexual Exploitation of Enslaved Women and its Impact on Slaveholding and Enslaved Communities. OCLC 950541239.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)