Jayhawker

Jayhawkers and red legs are terms that came to prominence in Kansas Territory, during the Bleeding Kansas period of the 1850s; they were adopted by militant bands affiliated with the free-state cause during the American Civil War. These gangs were guerrillas who often clashed with pro-slavery groups from Missouri, known at the time in Kansas Territory as "Border Ruffians" or "Bushwhackers." After the Civil War, the word "Jayhawker" became synonymous with the people of Kansas, or anybody born in Kansas.[1] Today a modified version of the term, Jayhawk, is used as a nickname for a native-born Kansan,[2][3][4] but more typically for a student, fan, or alumnus of the University of Kansas.

Origin

The origin of the term "Jayhawker" is uncertain. The term was adopted as a nickname by a group of emigrants traveling to California in 1849.[5] The origin of the term may go back as far as the Revolutionary War, when it was reportedly used to describe a group associated with American patriot John Jay.[6]

The term did not appear in the first American edition of Burtlett's Dictionary of Americanisms (1848),[7] but was entered into the fourth improved and enlarged edition in 1877 as a cant name for a freebooting armed man in the western United States.[8] The Farmer's Americanisms, old and new (1889) linked the term with anti-slavery advocates of late 1850s in Kansas.[9]

In 1858-1859, the slang term "Jayhawking" became widely used as a synonym for stealing.[10][11][12][13][14] Examples include:

O'ive been over till Eph. Kepley's a-jayhawking.[15]

Men are now at Fort Scott, working by the day for a living as loyal as Gen. Blunt himself, who have had every hoof confiscated, or jayhawked, which is about the same thing, for all the benefit it is to the Government.[16]

The term became part of the lexicon of the Missouri–Kansas border in about 1858, during the Kansas territorial period. The term came to be used to describe militant bands[17] nominally associated with the free-state cause. One early Kansas history contained this succinct characterization of the Jayhawkers:

Confederated at first for defense against pro-slavery outrages, but ultimately falling more or less completely into the vocation of robbers and assassins, they have received the name — whatever its origin may be — of jayhawkers.[18]

Another historian of the territorial period described the Jayhawkers as bands of men that were willing to fight, kill, and rob for a variety of motives that included defense against pro-slavery "Border Ruffians," abolition, driving pro-slavery settlers from their claims of land, revenge, and/or plunder and personal profit.[19]

While the "Bleeding Kansas" era is generally regarded as beginning in 1856, the earliest documented uses of the term "jayhawker" during the Kansas troubles were in the late 1850s, after the issue of slavery in Kansas had essentially been decided in favor of the Free State cause.[20][21] The earliest dated mention of the name comes from the autobiography of August Bondi, who came to Kansas in 1855. Bondi claimed that he observed General James Lane addressing his forces as Jayhawkers in December 1857.[22][23] Another early reference to the term (as applied to the Kansas troubles) emerging at that time is provided in the retrospective account of Kansas newspaperman John McReynolds. McReynolds reportedly picked up the term from Pat Devlin, a Free State partisan described as "nothing more nor less than a dangerous bully."[24] In mid-1858, McReynolds asked Devlin where he had acquired two fine horses that he had recently brought into the town of Osawatomie. Devlin replied that he "got them as the Jayhawk gets its birds in Ireland," which he explained as follows: "In Ireland a bird, which is called the Jayhawk, flies about after dark, seeking the roosts and nests of smaller birds, and not only robs nests of eggs, but frequently kills the birds." McReynolds understood Devlin had acquired his horses in the same manner the Jayhawk got its prey, and used the term in a Southern Kansas Herald newspaper column to describe a case of theft in the ongoing partisan violence. The term was quickly picked up by other newspapers, and "Jayhawkers" soon came to denote the militants and thieves affiliated with the Free State cause.[25][26]

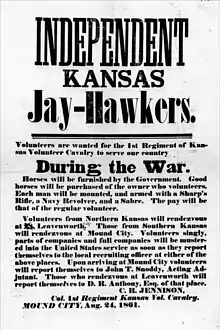

The meaning of the jayhawker term evolved in the opening year of the Civil War. When Charles Jennison, one of the territorial-era jayhawkers, was authorized to raise a regiment of cavalry to serve in the Union army, he characterized the unit as the "Independent Kansas Jay-Hawkers" on a recruiting poster. The regiment was officially termed the 7th Regiment Kansas Volunteer Cavalry, but was popularly known as Jennison's Jayhawkers.[27] Thus, the term became associated with Union troops from Kansas. After the regiment was banished from the Missouri–Kansas border in the spring of 1862, it went on to participate in several battles including Union victories of the Battle of Iuka and the Second Battle of Corinth. Late in the war, the regiment returned to Kansas and contributed to Union victory in one of the last major battles in the Missouri–Kansas theater, the Battle of Mine Creek.

The Jayhawker term was applied not only to Jennison and his command, but to any Kansas troops engaged in predatory operations against the civilian population of western Missouri, in which the plundering and arson that characterized the territorial struggles were repeated, but on a much larger scale. For example, the term "Jayhawkers" also encompassed Senator Jim Lane and his Kansas Brigade, which sacked and burned Osceola, Missouri in the opening months of the war after their defeat by Sterling Price's Missouri State Guard in the Battle of Dry Wood Creek.[28][29] Jayhawking was a prominent aspect of Union military operations in western Missouri during the first year of the war. In addition to Osceola, the smaller Missouri towns of Morristown, Papinsvile, Butler, Dayton, and Columbus and large numbers of rural homes were also burned by Kansas troops. Scores if not hundreds of Missouri families were burned out of their home in the middle of the winter. Union General Henry Halleck described Jennison's regiment as "no better than a band of robbers; they cross the line, rob, steal, plunder, and burn whatever they can lay their hands on."[30] There were no charges against Lane, Jennison, or other officers under Lane's command for their role in the jayhawking raids of 1861–1862, but Union General David H. Hunter succeeded in curtailing Lane's military role,[31] and units of Kansas troops such as the 7th Regiment Kansas Volunteer Cavalry were shuffled off to other theaters of the war.

Further compounding confusion over what the term Jayhawker meant along the Missouri–Kansas border was its use in describing outright criminals like Marshall Cleveland. Cleveland operated on a smaller scale, under cover of supposed Unionism, but was outside the Union military command.[32] A newspaper reporter traveling through Kansas in 1863 provided definitions of jayhawker and associated terms:[33]

Jayhawkers, Red Legs, and Bushwhackers are everyday terms in Kansas and Western Missouri. A Jayhawker is a Unionist who professes to rob, burn out and murder only rebels in arms against the government. A Red Leg is a Jayhawker originally distinguished by the uniform of red leggings. A Red Leg, however, is regarded as more purely an indiscriminate thief and murderer than the Jayhawker or Bushwhacker. A Bushwhacker is a rebel Jayhawker, or a rebel who bands with others for the purpose of preying upon the lives and property of Union citizens. They are all lawless and indiscriminate in their iniquities.

The depredations of the Jayhawkers contributed to the descent of the Missouri–Kansas border region into some of the most vicious guerrilla fighting of the Civil War. In the first year of the war, much of the movable wealth in western Missouri had been transferred to Kansas, and large swaths of western Missouri had been laid waste, by an assortment of Kansas Jayhawkers ranging from outlaws and independent military bands to rogue federal troops such as Lane's Brigade and Jennison's Jayhawkers. In February 1862, the Union command instituted martial law due to "the crime of armed depredations or jay-hawking having reached a height dangerous to the peace and posterity to the whole State (Kansas) and seriously compromising the Union cause in the border counties of Missouri."[34] One expert on the Jayhawkers stated that the Border War would have been bad enough given the fighting between secessionist and unionist Missourians, "but it was basically Kansas craving for revenge and Kansas craving for loot that set the tone of the war. Nowhere else, with the grim exception of the East Kentucky and East Tennessee mountains, did the Civil War degenerate so completely into a squalid, murderous, slugging match as it did in Kansas and Missouri."[35] The most infamous event in this war of raids and reprisals was Confederate leader William Quantrill's raid on Lawrence, Kansas known as the Lawrence Massacre.[36] In response to Quantrill's raid, the Union command issued Order No. 11, the forced depopulation of specified Missouri border lands. Intended to eliminate sanctuary and sustenance for pro-Confederate guerrilla fighters, it was enforced by troops from Kansas, and provided an excuse for a final round of plundering, arson, and summary execution perpetrated against the civilian population of western Missouri.[37] In the words of one observer, "the Kansas–Missouri border was a disgrace even to barbarism."[38]

As the war continued, the "Jayhawker" term came to be used by Confederates as a derogatory term for any troops from Kansas, but the term also had different meanings in different parts of the country. In Arkansas, the term was used by Confederate Arkansans as an epithet for any marauder, robber, or thief (regardless of Union or Confederate affiliation).[39] In Louisiana, the term was used to describe anti-Confederate guerrillas, as well as (in Texas) free-booting bands of draft dodgers and deserters.[40]

Over time, proud of their state's contributions to the end of slavery and the preservation of the Union, Kansans embraced the "Jayhawker" term. The term came to be applied to people or items related to Kansas.

Relationship to the University of Kansas Jayhawk

When the University of Kansas fielded their first football team in 1890, the team was called the Jayhawkers.[41] Over time, the name was gradually supplanted by its shorter variant, and KU's sports teams are now exclusively known as the Kansas Jayhawks.

Historic descriptions of the ornithological origin of the "Jayhawker" term have varied. Writing on the troubles in Kansas Territory in 1859, one journalist stated the jayhawk was a hawk that preys on the jay.[42] One of the "Jayhawkers of '49" recalled that the name sprang from their observation of hawks gracefully sailing in the air until "the audience of jays and other small but jealous and vicious birds sail in and jab him until he gets tired of show life and slides out of trouble in the lower earth."[5] In the Pat Devlin stories, the jayhawk is described more in terms of its behavior (bullying, robbing, and killing) than the type of bird it is.[43]

The link between the term "Jayhawkers" and any specific kind of bird, if such an association ever existed, had been lost or at least obscured by the time KU's bird mascot was invented in 1912, which was meant to serve as a visual representation of the Jayhawker movement, an homage by the university to the state's history. The originator of the bird mascot, Henry Maloy, struggled for over two years to create a pictorial symbol for the team, until hitting upon the bird idea. As explained by Maloy, "the term 'jayhawk' in the school yell was a verb and the term 'Jayhawkers' was the noun."[44]

In 2011, the city of Osceola, Missouri produced a declaration condemning what city leadership viewed as a connection between the Jayhawk mascot and the historical Jayhawkers who burned the town in 1861.

In 2017, the Kansas football team unveiled uniforms with an American flag on the helmet, blue jerseys, and red pants which featured the words "Kansas Jay-Hawkers" above a seal featuring a sword and a rifle. Kansas Athletics stated that the red pants was an homage to the term "Redlegs," another name for Jayhawkers.

Cultural influence

- Plunderers and militant abolitionists were referred to as "Jayhawkers" or "Red Legs" and both were used as terms of derision towards those from Kansas after the Civil War. The term "Jayhawk" has evolved over the years to a term of pride used by some Kansans. The term "Red Leg" as applied to Kansans has disappeared from common lexicon.

- Items stolen in raids into Missouri were frequently referred to as having been "Jayhawked."

- The Jayhawkers are featured prominently in Lloyd Alexander's historical novel, "Border Hawk: August Bondi."

- In the Gunsmoke radio show episode "Texas Cowboys" (1954 Radio), Jayhawkers follow a cattle drive and continue to stampede the herd. Marshal Matt Dillon allows the cowboys to "hurrah" Dodge. Jayhawkers were also the subject of the October 16, 1955 episode "Trouble in Kansas."

- A cattle drive being held up by Jayhawkers is depicted in The Tall Men (1955).

- In a 1959 Gunsmoke episode called "The Jayhawkers," men of that name try to extort money from cattle-drivers by threatening to scatter their herds unless paid off.

- The movie The Jayhawkers! (1959) depicts a charismatic leader (Jeff Chandler) of a new independent Republic of Kansas in a showdown with an ex-renegade raider (Fess Parker), sent by the military governor to capture him and bring him to justice.

- In a 1961 Rawhide episode called "Incident of the Phantom Bugler" a group referred to as Jayhawkers attempt to extort money from Gil Favor and crew to cross river.

- Clint Eastwood's Missourian character in the film The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) took up the Confederate cause after Redleg Jayhawkers from Kansas killed his son and raped and murdered his wife.

- Jayhawker Colonel James Montgomery was portrayed as a racist, vengeful, and larcenous commander of a black regiment in the 1989 film Glory, where he is referred to as "a real Jayhawker from Kansas."

- The 1999 movie Ride With the Devil, directed by Ang Lee, and starring Tobey Maguire, Skeet Ulrich, and Jewel depicts Jayhawkers raiding Missouri homesteads.

- The 2014 movie Jayhawkers, directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker Kevin Willmott, follows the college career of Wilt Chamberlain and the 1956 Kansas Jayhawks basketball team.

- An alternative country/alternative rock band originating in the 1980s from Minneapolis, Minnesota is named The Jayhawks.

- An unincorporated community in El Dorado County, California is named Jayhawk, California.

- The Wichita, Kansas wing of the Commemorative Air Force is known as the Jayhawk Wing.

- The VII Corps of the United States Army official nickname was The Jayhawk Corps.

- The United States Army Company A of the 9th aviation battalion of the 9th Infantry Division official nickname was The Jayhawks.

- The United States Coast Guard operates the medium range twin engine helicopter HH-60 Jayhawk in the roles of maritime patrol, interdiction, and search and rescue.

- The United States Navy operates the AQM-37 Jayhawk high speed target drone.

- The United States Air Force and the Japan Air Self-Defense Force operate the advanced pilot trainer T-1 Jayhawk for students selected to fly strategic/tactical airlift or tanker aircraft.*The 184th Intel Wing call sign is the Fighting Jayhawks, and previously the Flying Jayhawks for many years before losing assigned aircraft.

See also

Notes

- Mechem, Kirke (1944). "The Mythical Jayhawk". Kansas Historical Quarterly. Kansas Historical Society. 13 (1): 1–15. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- Jayhawker - Dictionary.com

- Jayhwaker - Merriamwebster.com

- Jayhawker - Thefreedictionary.com

- Fox, Simeon M. "The Story of the Seventh Kansas." Transactions of the Kansas State Historical Society 8(1904): 13-49.

- The Daily Cleveland Herald, (Cleveland, OH) Saturday, December 21, 1861. Issue 301; column B

- Dictionary of Americanisms (1848)

- Bartlett, John Russell. Dictionary of Americanisms. A glossary of words and phrases, usually regarded as peculiar to the United States; Fourth edition, greatly improved and enlarged. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1977, p. 321

- Farmer, John Stephen. Americanisms - Old & New: a Dictionary of Words, Phrases And Colloquialisms Peculiar to the United States, British America, the West Indies, Etc. Etc., Their Derivation, Meaning And Application, Together With Numerous Anecdotal, Historical, Explanatory, And Folk-lore Notes. London: T. Poulter, 1889, p. 323.

- Robley, History of Bourbon County Kansas, 95;

- Cutler, History of the State of Kansas, 1:878.

- William Anselm Mitchell, Linn County, Kansas: A History (Kansas City, Kans.: Campbell-Gates, 1928), 22

- Daniel W. Wilder, Annals of Kansas: 1541–1885 (Topeka: Kansas Publishing House, 1875), 615–16; Starr, Jennison's Jayhawkers, 29

- Kansas Magazine 3 (1873), 553.

- Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 34 (Summer 2011):, 117

- Pearl T. Ponce, Kansas's War: The Civil War in Documents (Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio, 2011) p. 174

- Missourians were called "Bushwackers" and Kansas "Jayhawkers."

- Spring, Leverett Wilson. Kansas, The Prelude to the War for the Union. New York: Boston Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1896

- Welch, G. Murlin. Border Warfare in Southeast Kansas: 1856-1859. Linn County Publishing Co., Inc. 1977.

- Welch, G. Murlin. Border Warfare in Southeast Kansas: 1856–1859. Linn County Publishing Co., Inc. 1977. Chapter XV, End note No. 20.

- Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history, embracing events, institutions, industries, counties, cities, towns, prominent persons, etc. Standard Pub. Co. Chicago : 1912. Vols. I–II edited by Frank W. Blackmar. "Jayhawkers" entry Archived 2009-03-22 at the Wayback Machine. Transcribed July 2002 by Carolyn Ward. Accessed January 21, 2011.

- August Bondi, Autobiography (Galesberg, Ill.: Wagoner Printing Co., 1911), 33–34, 6

- http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/bitstream/1808/8265/1/Kansas%20History_v33_4_lane_final.pdf

- "The Kansas War, The Disturbances in Southern Kansas – Brown and Montgomery." New York Times, January 28, 1859.

- "Origin of the Word Jayhawking In Application to the People of Kansas. Incidents in the early History of the Territory." The Allen County Courant (Iola, Kansas), May 23, 1868; Vol. 2, No. 19.

- "Origin of the Word 'Jayhawking'". The (Junction City) Smoky Hill and Republican Union. June 18, 1864.

- Starr, p. 57.

- Goodrich, Thomas. Black Flag: Guerrilla Warfare on the Western Border, 1861–1865. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1995.

- Benedict, Bryce. Jayhawkers: The Civil War Brigade of James Henry Lane. University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

- Starr, p. 96.

- Castel, Civil War Kansas, pp. 77–80.

- Starr

- Connelly, William E. Quantrill and the Border Wars. Cedar Rapids, Iowa: The Torch Press. 1910. p. 412.

- General Order No. 17; Headquarters Department of Kansas, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, February 8, 1862.

- Starr, p. 50.

- ICastel, Albert. Kansas Jayhawking Raids Into Western Missouri in 1861. Missouri Historical Review 54/1. October 1959.

- Bingham, George Caleb. Address to the public, vindicating a work of art illustrative of the federal military policy in Missouri during the late civil war. Kansas City, MO. 1871.

- Robinson, Charles. The Kansas Conflict. 1892. Reprint. Lawrence, Kans.: Journal Publishing Co., 1898. p. 455.

- Daniel E. Sutherland. "Jayhawkers and Bushwackers." The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture.

- Block, William T. Some Notes on the Civil War Jayhawkers of Confederate Louisiana.

- The University of Kansas, "Traditions, The Jayhawk" Archived 2012-11-15 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed January 28, 2011.

- The Daily Tribune (Manitowoc, WI), February 4, 1859, page 1, column A. From the N.Y. Tribune.

- T. F. Robley, History of Bourbon County. Fort Scott: Press of the Monitor Book & Print. Co., 1894, p.96.

- Kirke Mechem. The Mythical Jayhawk. Kansas Historical Quarterly, February 1944 (Vol. 13, No. 1), pages 1 to 15.

References

- Castel, Albert (1997). Civil War in Kansas: Reaping the Whirlwind. (ISBN 0-7006-0872-9)

- Kerrihard, Bo. "America's Civil War: Missouri and Kansas." TheHistoryNet.

- Starr, Steven Z. (1974). Jennison's Jayhawkers: A Civil War Cavalry Regiment and its Commander. (ISBN 0-8071-0218-0)

- Wellman, Paul. (1962) A Dynasty of Western Outlaws (details the origins of the James-Younger and other outlaw gangs in the Kansas-Missouri border war).

External links

Media related to Jayhawkers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jayhawkers at Wikimedia Commons- Seventh Regiment (Jennison's Jayhawkers) Kansas Volunteer Cavalry, Kansas Historical Society

- "The Mythical Jayhawk," Kansas Historical Quarterly, Kansas Historical Society

- Cool Things - Pogo Comic Strip featuring Jayhawk, Kansas Historical Society

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.