Jisr Jindas

Jisr Jindas, Arabic for "Jindas Bridge",[1] also known as Baybars Bridge, was built in 1273 C.E. It crosses a small wadi, known in Hebrew as the Ayalon River, on the old road leading south to Lod and Ramla.[2] The bridge is named after the village of Jindas, which until 1948 stood east of the bridge[3] and may have been the Crusader-period "casal of Gendas" mentioned in a Latin charter dated 1129 CE.[4] It is the most famous of the several bridges erected by Sultan Baybars in Palestine, which include the Yibna and the Isdud bridges.[5]

Jisr Jindas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 31°58′N 34°54′E |

| Carries | |

| Crosses | Ayalon River |

| Locale | Lod, Israel |

| Official name | Jisr Jindas |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Arch |

| Total length | 30 metres |

| Width | 10 metres |

| History | |

| Opened | 1273 CE |

| Location | |

| |

History

The present structure dates to AH 672/AD 1273, but is believed to be constructed on Roman foundations.[6] It was first studied in modern times by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau, who noted that an Arabic chronicle had referred to the construction by Baybars in AH 672 of two bridges of a significant nature "in the neighbourhood of Ramleh".[7] The second of these two bridges is thought to be the Yibna Bridge.[7]

Clermont-Ganneau concluded that the bridge was built using masonry reclaimed from the Church of Saint George, which had been destroyed in the Crusader-Ayyubid War.[7]

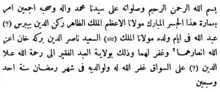

On the west and east faces of the bridge are two nearly identical inscriptions, flanked by two lions (or leopards). The inscription on the east reads as follows:

Bismallah..., and blessings on their lord Muhammad, his family and his companions. The building of this blessed bridge was ordered by their master, the great Sultan al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars, ibn Abd Allah, in time of his son their Lord Sultan al-Malik al-Said Nasir al-Din Baraka Khan, may Allah glorify their victories and grant them His grace. And that, under the direction of the humble servant aspiring to the mercy of Allah. Ala al-Din Ali al-Suwwaq, may Allah grant grace to him and his parents, in the month of Ramadan, the year 671 H. [March–April 1273 C.E.]

Ala al-Din Ali al-Suwwaq was the same official charged with overseeing the construction of the Great Mosque of Lydda three years earlier.[8]

In 1882 the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine noted that Jisr Jindas had a representation of two lions and an Arabic text. It further noted that it appeared to be "Saracenic work".[9]

Description

The bridge is over 30 metres (98 ft) long and 10 metres (33 ft) wide, and runs north-south. It consists of three arches and two central piers, with the central arch wider than the two other arches.[2]

Baybars panthers or lions

In his native Turkic language, Baibars' name means "great panther".[10] Possibly based on that, Baibars used the panther as his heraldic blazon, and placed it on both coins and buildings.[10] On the Bridge of Jindas, the lions/panthers used play with a rat, which may be interpreted to represent Baibars' Crusader enemies.[11]

According to Moshe Sharon, the lions on Jisr Jindas are similar to the ones on the Lions' Gate in Jerusalem, and Qasr al-Basha in Gaza. All represent the same sultan: Baybars. The Gaza lions were created with interlocking lines suggesting leopard spots, however, the felines' outline is similar. Sharon estimates that they all date to approximately 1273 C.E.[12]

- Baibars' lions

Baibars' lion on the Bridge of Jindas

Baibars' lion on the Bridge of Jindas Baibars' lions on Lions' Gate, Jerusalem

Baibars' lions on Lions' Gate, Jerusalem Baibars' lion from Qal'at al-Subeiba, at the foot of Mount Hermon

Baibars' lion from Qal'at al-Subeiba, at the foot of Mount Hermon

References

- "The bridge of Jindas", according to Palmer, 1881, p. 215

- Petersen, 2001, p. 183

- The Israeli Association "Zochrot", which keeps an online record of all villages and towns destroyed or depopulated during the 1948 Palestinian exodus, records the date of Jindas' occupation by the newly-founded Israeli army as July 1, 1948 .

- Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, vol.2, p. 117, who quotes the Cartulaire général de l'ordre des Hospitaliers, no.84

- Petersen, 2008, p. 297

- O’Connor, 1993

- Clermont-Ganneau, 1896, vol.2, pp.110–117

- Petersen, 2001, p. 184

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, pp. 264–5

- Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh (2004). The image of an Ottoman city: imperial architecture and urban experience in Aleppo in the 16th and 17th centuries. Brill. p. 198. ISBN 90-04-12454-3.

- Niall Christie (2014). Muslims and Crusaders: Christianity’s Wars in the Middle East, 1095-1382, from the Islamic Sources. Seminar Studies (first ed.). Routledge. p. 121, Plate 8. ISBN 9781138022744.

- Sharon, 2009, p. 58 and pl.6.

Bibliography

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S., "Le pont de Beibars à Lydda." In Recueil d'archéologie orientale. Clermont-Ganneau, Charles. 262–279. Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1888. (editio princeps)

- Clermont-Ganneau, C.S. (1896). [ARP] Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873–1874, translated from the French by J. McFarlane. 2. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- O’Connor, Colin (1993), Roman Bridges, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-39326-4

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Petersen, A. (2008): Bridges in Medieval Palestine, in U. Vermeulen & K. Dhulster (eds.), History of Egypt & Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid & Mamluk Eras V, V. Peeters, Leuven

- Sharon, M. (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, B-C. 2. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11083-6. p.229: "From Ramlah the route continued to Ludd (Lydda) and over a bridge (near Jindas) to the north of the city built in 1273, up to the khan of Jaljulyah, built around 1325."

- Sharon, M. (2009). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, G. 4. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-17085-5.

External links

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons