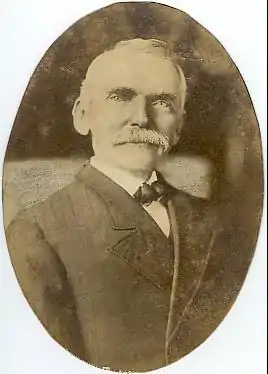

John Baptist Smith

John Baptist Smith (1843–1923) is believed by some to have provided the most lasting contribution made by either side during the American Civil War. In 1862 he invented and helped build a lantern system of naval signaling.

He was born September 19, 1843, at Hycotee in Caswell County, North Carolina, the son of Richard Ivy Smith (1800–1871) and Mary Amis Goodwin Smith (1815–1889). At seventeen, he joined the Milton Blues to fight in the Civil War. Rapidly promoted and transferred to the Signal Corps, he soon was a sergeant in charge of a Confederate signaling station on the James River at Newport News, Virginia. While there he witnessed the naval battle between the Confederate ironclad Virginia when it destroyed the federal frigates Cumberland and Congress in the James River. When Norfolk was evacuated, Sgt. Smith and his signal corps were ordered to Petersburg, Virginia and given charge of the signal station on the Appomattox River to observe the movement of the enemy fleet and forces. While occupying an exposed position that was often under siege, he and his men held fast. Smith and his men also rendered valuable service during the seven day's fight around Richmond and the retreat of McClellan's army.

In July 1862 Smith was ordered by the Confederate Secretary of War to the Cape Fear River region of North Carolina to assist in organizing the signal service. He was placed in charge of the important station at Fort Fisher under Colonel William Lamb. Being concerned with establishing signal communication between forts at the mouth of the river he focused on the following: "I soon observed the great difficulty a vessel encountered in her effort to enter our port," he later recalled, "and at once began to study how this obstacle might be overcome." The Cape Fear River was used by Confederate blockade-running vessels bringing essential supplies to the South, and anything that could be done to speed their entry and ensure their safe arrival would be welcomed.

One day while in the ordnance department of the Fort, I chanced to spy a pair of ship starboard and port lanterns, and this thought flashed into my mind, "Why not by the arrangement of a sliding door to each of these lanterns, one being a white, the other a red light, substitute flashes of red and white lights for the wave of torches to the right and left, to form a signal alphabet and thus use the lanterns at sea as well as upon land." I at once communicated my plans to Col. Wm. Lamb, commandant of the fort. They met his approbation and I was instructed to submit them to Gen. Whiting commanding the department, who most readily gave me an order to the master of the machine shop at Wilmington, to render me aid in fitting up my lanterns. These, under my personal directions, were speedily fixed to my entire satisfaction. The General then referred me to Commodore Lynch, who ordered a commission of Naval Officers to investigate my mode of signaling by flash lights. This commission, after careful investigation, were so highly impressed with the system that upon their recommendation it was adopted and ordered to be operated on all the Confederate Blockade Runners. To this end, a pair of my lanterns and a Signal Officer were placed on each one of them. Signal stations were also established along the coast, so that an incoming vessel, when she made our coast, would run along as close ashore as possible and her Signal Officer, by flashing his light from the shore-side of the ship, could escape observation by the Blockaders, get the attention of the shore stations, and thus ascertain the position of his ship and send a message to the commandant of the fort to set range lights, by which the pilot could steer his vessel across the bar and have the guns of the fort manual to protect the vessel if necessary.

This successful method of signaling at night was most effective and the advantages of it over the old torches was immediately recognized. Smith reported that a British ship captain whom he met shortly afterwards "urged me to go to England with him and take out letters patent from the British and other European Governments; he agreed to bear all expenses in consideration of an interest in the patent. I declined his most liberal offer because it would to my mind, look like deserting my country in her hour of need, although I was certain I might have obtained permission from the Confederate Secretary of Navy to carry out this proposition, which most certainly would have been a source of great profit pecuniarily, as it has formed the basis of the present system now used in the Naval service generally."

In recognition of the valuable contribution that Sgt. Smith had made, the Secretary of War assigned him for special duty with General Whiting at Wilmington. The general gave Smith his choice of vessels upon which to serve as signal officer, and he chose the Advance, a state-owned blockade runner recently purchased at Liverpool and perhaps the fastest ship afloat. Smith served well in this capacity until February, 1864, when he was commissioned lieutenant in the Signal Corps and ordered to report for duty at Petersburg. He was given command of the signal station on the lower James River with headquarters at Hardy's Bluff, the lowest outpost of the Confederate army. From this vantage point he relayed detailed reports of the number and movement of the enemy gunboats and transports until the line of communication was broken and he was forced to fall back to Petersburg. In that beleaguered city he and his men fought in the trenches as infantry for forty-eight hours without relief of any kind. Because of his recognized ability and bravery, Lt. Smith was given command of the signal lines from Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard's headquarters. A few days later he was ordered to report in person to Gen. Lee who placed him in command of the signal lines running from his own headquarters to the different points around Petersburg. This has been called "perhaps the highest compliment bestowed in the Confederate States Army upon so youthful an officer."

In 1865 Lt. Smith's men were the last to leave Petersburg, crossing the last bridge as it burned. They served as a rear guard for Gen. Lee's army, and were present at Appomattox Court House where Smith released some Federal prisoners who had been taken along from Petersburg. Smith secured paroles for his men and returned home to Caswell County, arriving on April 15, 1865, four years to the day after his enlistment.

In 1872, he married Sabra Annie Long. The couple produced eight children. He is buried at the Red House Presbyterian Church near the place he was born in Caswell County, North Carolina. For more on the family of John Baptist Smith go to the Caswell County Family Tree.

References

- The Heritage of Caswell County, North Carolina, Jeannine D. Whitlow, Editor (1985)

- When the Past Refused to Die: A History of Caswell County North Carolina 1777-1977, William S. Powell (1977)