John Salusbury (diarist)

Sir John Salusbury (1 September 1707 – 2 May 1762) was a Welsh nobleman, explorer and co-founder of Halifax, Nova Scotia. He is credited as being one of the founders of modern Canada along with several other members of his expedition, including the Earl of Halifax and Edward Cornwallis. He served on the Nova Scotia Council throughout Father Le Loutre's War. He participated in the Battle at Chignecto. His diaries regarding the military campaign to establish a colony in Nova Scotia on behalf of the British Government became a vital source of information regarding the hardships, difficulties and opposition from the average Englishman regarding the development of the colony. He was a direct descendant of Katheryn of Berain.

Early life

John Salusbury was born to Thomas Salusbury of Bachygraig, Flintshire and his wife and first cousin, Lucy Salusbury.[1] He was a member of the Salusbury family, a family of powerful oligarchs in Wales which at the time controlled most of Denbighshire along with their cousins, the Cotton baronets. Salusbury's early years were relatively uneventful; he received his primary education in Denbigh and later went to Rugby School and Westminster School as his parents fortune ebbed and flowed. As a young man, he received his collegiate training in Mathematics at Trinity Hall, Cambridge,[2] as did his younger brother, Thomas, although the latter eventually graduated in Law. The education of the two eldest sons (a third, Henry, was most likely retarded), combined with bad financial planning by his father, virtually decimated the family fortune and by the time of his father's death in 1714, John found that the majority of his lands were mortgaged to the Crown.

After his father's inheritance, Salusbury bought a small house in London's Soho Square and, finding himself unable to pay off the rest of his debts worked as a fortune hunter, and according to court gossip, as a gigolo. Unable to receive a position at court due to his father's reputation for intrigues, John travelled abroad as a companion to his cousin, Sir Robert Cotton, 3rd Baronet. During that time, Cotton paid for the majority of John's expenses during the journey which served as a Grand Tour for both men. The two-year journey with Cotton ended in France, where Salusbury had received a position with the French court at Versailles and again served as a companion, this time to the young wife of the elderly Duc de Noailles with whom he probably had a romantic liaison.

Having exhausted his time at Versailles, in part due to the anti-English sentiment then in France, Salusbury returned to England where he found his family's estates, Lleweni Hall and Bach y Graig mortgaged to the hilt by his brother who had taken out large loans to sustain his gambling debts in London.

To save the estates from foreclosure they turned to their cousin, who had then been then unaware of the family's financial troubles. Cotton was forced to pay a large indemnity to what were probably Jewish bankers, signified by Salusbury's daughter's early writings which indicated a significant amount of anti-semitic prose (she would later in life change her views and become literate in Hebrew). By 1738, the debts created by his brother would make the maintenance of his estates untenable and Cotton used his influence to appoint Salusbury to both relieve Salusbury's extensive debt and appoint him to several influential positions in the shire. In exchange, Salusbury married Cotton's sister, Hester, in 1739.

Married life

With his debts resolved and his estates finally deriving an income for the young family, John moved to Bodvel Hall, a small estate of the family's in Caernarvonshire. He focused much of his time on balancing his books, making allowances for his mother, for whom he spared no expense, and his brother, who insisted on living a rather lavish life in London at his brother's expense. He would finally see his wife Hester give birth to his only child, also named Hester, in 1741.

When his mother at last died in 1745, Salusbury found his financial predicament again in trouble as Lucy had accumulated significant debts in and around Denbigh. His cousin Lynch Cotton, however, was able to rescue the family from poverty by naming Hester as benefactor during this period, allowing for the family to move back to London. In 1747 they did so in a smaller house in Abermarle Street having previously rented their home in Soho Square to Thomas. For approximately one year, Salusbury functioned as a courtier, having finally been allowed to re-enter London society. However, when Cotton died the next year in 1748, Salusbury found to his dismay that the will had been lost, probably destroyed by the inheritor, Sir Lynch Cotton, his distantly removed cousin. Without any options John rapidly became violent, according to Hester's writings, and drifted into what was probably clinical depression by today's standards.

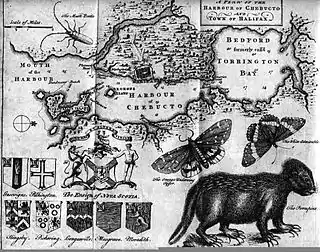

Nova Scotia

In 1749 Salusbury left for Nova Scotia with a strong dislike for the colony which he thought beneath his station. He was there for the founding of Halifax. But Salusbury, who had no idea about how to manage his income, began to deplete it rapidly despite his ownership of a large farm of 130 acres (0.53 km2) in what is now Herring Cove. During his tenure in Canada, he spent much of his time as a magistrate for the colony, finding life difficult and complaining in his diary that his crops were virtually worthless as they had to be shipped to London to be sold in accordance with the policy of mercantilism.

Dispassionate about Nova Scotia, Salusbury was a virtual outsider in his own circle. Although a member of the colonial council which governed the colony under the auspices of the Viceroy of Nova Scotia, Salusbury was passive in his own advancement, preferring to demur about his accomplishments. Though affable, he was prone to jealousy which made him resent the few people above his station, which ironically destroyed his prospects for advancement. In response, he began a diary in which he described the colony from a unique perspective: Salusbury was an outsider, considered by many of his peers who were socially below his station but above him in rank as a pest, and therefore someone to be ignored; yet he was privy to the inner workings of the colony much of which required his approval as head of the justice system.

He returned to England briefly in 1751 in order to manage personal business, but after his return in 1752 he reported to the Earl of Halifax that the colony was even worse off than before — now political factions vied for power. His general negativity, political neutrality and unabashed dislike for the un-cosmopolitan colony disqualified him for the governorship, which ultimately went to one of his few rivals, Peregrine Hopson. In 1753 he returned to London having made no profit with the exception of the sale of his farm for a small sum. He was "gloriously out of humour" when he learned that Thomas had further mismanaged the Welsh estates which were again mortgaged. During this time, the family resumed its residence at Soho Square, living on a small annuity derived from the Crown and from their lands in Wales.

Later life

During Salusbury's remaining years his financial position and that of his brother were switched, and by 1759 he had begun to receive large payments from Thomas who was by then a high-ranking judge for the High Court of Admiralty. Thomas had married exceptionally well, and when his wife died the following year, it was John who was placed in charge of the significant inheritance which Thomas had received. This enabled John to live well and over the years he would entertain several personalities whom he met during his time in Nova Scotia, including Charles Lawrence, Jonathan Belcher and Edward Cornwallis. He also began to cultivate a small salon in Soho Square where he encouraged education and began a family tradition of patronage of the arts starting with William Hogarth, whom Hester recorded as virtually living with the family until his death (she would later herself become the patron of Samuel Johnson).

In 1761, Salusbury died of an apoplectic stroke after learning that Hester was to marry Henry Thrale, a wealthy brewer whose father had the misfortune of being born in a dog kennel on one of Salusbury's estates, and that his brother Thomas was to marry a poor widow who had borne a child from her first marriage which would therefore disqualify John from the inheritance.

Modern reputation

John's legacy is perhaps best encapsulated in his journals, which thoroughly describe the daily life and problems encountered by both the colonists and the British government in the settlement of Nova Scotia. While many of his comments were undoubtedly personal, they were also trite, offering a solution to many of the problems created by the colonial-era government of Nova Scotia.

While Salusbury may have found Nova Scotia to be dull, his reputation as a qualified and competent civil servant was cemented in the eyes of the colonists. As the St. Paul's Church register shows, parents named their children after Salusbury—and he even acted as godparent to several of them in many circumstances. Although kindly and charming on the outside, John's journals showed him to be a sensitive individual who took offence to the slightest criticisms and often sulked at his lack of promotion.

Salusbury's is the namesake of the house that was built on his land in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia (1830).[3]

Notes

- Debrett's Baronetage of England (1839)

- "Salisbury, John (SLSY724J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- John Salisbury House. Canadian Register of Historic Places.

References

- Rompkey, Ronald, ed. Expeditions of Honour: The Journal of John Salusbury in Halifax, Nova Scotia (1749–1753). London: Associated University Press, 1980.

- Maritime Treaties – a list with Treaties pertaining to the settlement of Nova Scotia, many of which John composed or signed

- Rompkey, Ronald (1974). "Salusbury, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. III (1741–1770) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.