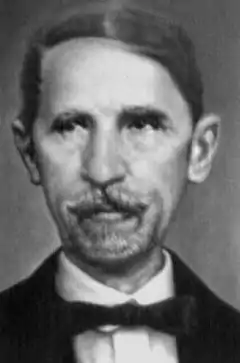

Juan Pablo Duarte

Juan Pablo Duarte (January 26, 1813 – July 15, 1877)[1] was a Dominican military leader, writer, activist, and nationalist politician who was the foremost of the founding fathers of the Dominican Republic. As one of the most celebrated figures in Dominican history, Duarte is considered a folk hero and revolutionary visionary in the modern Dominican Republic, who along with military general Ramon Matias Mella and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, organized and promoted the Trinitario movement that eventually led to the Dominican revolt and independence from Haitian rule in 1844 and the start of a Dominican love of Independence.

In 1842, Duarte became officer in the National Guard and a year later in 1843 he participated in the "Reformist Revolution" against the dictatorship of Jean Pierre Boyer, who threatened to invade the western part of the island with the intention of unifying it. After the defeat of Haitian President and the proclamation of Dominican independence in 1814, the Board formed to designate the first ruler of the nation and elected Duarte by an strong majority vote to preside over the nation but he declined the proposal, while Tomás Bobadilla took offce instead.[2]

Duarte helped inspire and finance the Dominican War of Independence, paying a heavy toll which would eventually ruin him financially. Duarte also disagreed strongly with royalist and pro-annexation sectors in the nation, especially with the wealthy caudillo and military strongman Pedro Santana, who sought to rejoin the Spanish Empire. From these struggles, Santana emerged victorious while Duarte suffered in exile, living in Venezuela until his death in 1876.

Early years

Duarte was born on 26 January 1813 in Santo Domingo, Captaincy General of Santo Domingo[1] during the period commonly called España Boba. In his memoirs, the trinitarian José María Serra de Castro described Duarte as a man with a rosy complexion, thin lips, blue eyes, and a golden hair that contrasted with his thick, dark moustache.[3]

Duarte was born into a middle-class family that was dedicated to maritime trade and hardware in the port area of Santo Domingo.[4] His father was Juan José Duarte Rodríguez, a Peninsular from Vejer de la Frontera, Kingdom of Seville, Spain, and his mother was Manuela Díez Jiménez from El Seibo, Captaincy General of Santo Domingo; three of Duarte's grandparents were Europeans.[lower-alpha 1] Duarte had 9 siblings: his eldest brother, Vicente Celestino Duarte (1802–1865), a tall, long-haired brunette man, was a store owner, woodcutter and cattle rancher who was born in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico; one of Duarte's sisters was Rosa Protomártir Duarte (1820–1888), a performer who collaborated with him within the Independence movement. In 1802 the Duarte family migrated from Santo Domingo to Mayagüez, Puerto Rico.[6] They were evading the unrest caused by the Haitian Revolution in the island. Many Dominican families left the island during this period.[7] Toussaint Louverture, governor of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), a former colony of France located on the western third of Hispaniola,[8][9] arrived to the capital of Santo Domingo, located on the island's eastern two-thirds, the previous year and proclaimed the end of slavery (although the changes were not permanent). At the time, France and Saint-Domingue (the western third of the island), were going through exhaustive social movements, namely, the French Revolution and the Haitian Revolution. In occupying the Spanish side of the island L'Ouverture was using as a pretext the previous agreements between the governments of France and Spain in the Peace of Basel signed in 1795, which had given the Spanish area to France.

Upon arrival in Santo Domingo, Louverture immediately sought to abolish slavery in Dominican territory, although complete abolition of slavery in Santo Domingo came with renewed Haitian presence in early 1822. Puerto Rico was still a Spanish colony, and Mayagüez, being so close to Hispaniola, just across the Mona Passage, had become a refuge for wealthy migrants from Santo Domingo like the Duartes and other native born on the Spanish side who did not accept Haitian rule. Most scholars assume that the Duartes' first son, Vicente Celestino, was born here at this time on the eastern side of the Mona Passage. The family returned to Santo Domingo in 1809, however, after the Spanish reconquest of Santo Domingo.

In 1819, Duarte enrolled in Manuel Aybar's school where he learned reading, writing, grammar and arithmetic. He was a disciple of Dr. Juan Vicente Moscoso from whom he obtained his higher education in Latin, philosophy and law, due to the closure of the university by the Haitian authorities. After the exile of Dr. Moscoso to Cuba, his role was continued by the priest Gaspar Hernández.

Family lineage

| Ancestors of Juan Pablo Duarte |

|---|

| [5] |

The struggle for independence

In December 1821, when Duarte was eight years old, members of a Creole elite of Santo Domingo's capital proclaimed its independence from Spanish rule, calling themselves Haití Español. Historians today call this elite's brief courtship with sovereignty the Ephemeral Independence. The most prominent leader of the coup against Spanish colonial government was one of its former supporters, José Núñez de Cáceres. These individuals were tired of being ignored by the Crown, and some were also concerned with the new liberal turn in Madrid.

Their deed was not an isolated event. The 1820s was a time of profound political changes throughout the entire Spanish Atlantic World, which affected directly the lives of middle-class like the Duartes. It began with the conflictive period between Spanish royalists and liberals in the Iberian Peninsula, which is known today as the Trienio Liberal. American patriots in arms, like Simón Bolívar in South America, immediately reaped the fruits of Spain's destabilization, and began pushing back colonial troops. Even conservative elites in New Spain (like Agustín de Iturbide in Mexico), who had no intention of being ruled by Spanish anticlericals, moved to break ties with the crown in Spain.

Many others in Santo Domingo wanted independence from Spain for reasons much closer to home. Inspired by the revolution and independence on the island, Dominicans mounted a number of different movements and conspiracies in the period from 1809-1821 against slavery and colonialism.[10] Several towns asked for Haiti to help with Dominican independence weeks before the experiment of Haití Español even began.[11]

The Cáceres provisional government requested support from Simón Bolivar's new government, but their petition was ignored given the internal conflicts of the Gran Colombia.[12] Meanwhile, a plan for unification with Haiti grew stronger. Haitian politicians wanted to keep the island out of the hands of European imperial powers and thus a way to safeguard the Haitian Revolution . Haiti's President Jean-Pierre Boyer sent an army that took over the eastern portion of Hispaniola. Haiti then abolished slavery there once and for all, and occupied and absorbed Santo Domingo into the Republic of Haiti. Struggles between Boyer and the old colonial helped produce a migration of planters and elite. It also led to the closing of the university. Following the bourgeoisie custom of sending promising sons abroad for education, the Duartes sent Juan Pablo to the United States and Europe in 1828 .

On July 16, 1838, Duarte and others established a secret patriotic society called La Trinitaria, which helped undermine Haitian occupation. Some of its first members included Juan Isidro Pérez, Pedro Alejandro Pina, Jacinto de la Concha, Félix María Ruiz, José María Serra, Benito González, Felipe Alfau, and Juan Nepomuceno Ravelo. Later, Duarte and others founded a society called La Filantrópica, which had a more public presence, seeking to spread veiled ideas of liberation through theatrical stages. All of this, along with the help of many who wanted to be rid of the Haitians who ruled over Dominicans led to the proclamation of independence on February 27, 1844 (Dominican War of Independence). However, Duarte had already been exiled to Caracas, Venezuela the previous year for his insurgent conduct. He continued to correspond with members of his family and members of the independence movement . Independence could not be denied and after many struggles, the Dominican Republic was born. A republican form of government was established where a free people would hold ultimate power and, through the voting process, would give rise to a democracy where every citizen would, in theory, be equal and free.

Duarte was supported by many as a candidate for the presidency of the new-born Republic. Mella wanted Duarte to simply declare himself president. Duarte never giving up on the principles of democracy and fairness by which he lived, would only accept if voted in by a majority of the Dominican people . Duarte had a definite concept of the Dominican nation and its members. His conception of a republic was that of a republican, anticolonial, liberal and progressive patriot. At that time he drafted a draft constitution that clearly states that the Dominican flag can shelter all races, without excluding or giving predominance to any. However, the forces of those favoring Spanish sovereignty as protection from continued Haitian threats and invasions, led by general Pedro Santana, a large landowner from the eastern lowlands, took over and exiled Duarte. In 1845, Santana exiled the entire Duarte family. After more but unsuccessful Haitian invasions, internal disorder, and his and others’ misrule, Santana turned the country back into a colony of Spain in 1861, was awarded the hereditary title of Marquess of Las Carreras by the Spanish Queen Isabella II, and died in 1864.

Duarte's family in Venezuela did not do too badly, they lived and worked in an affluent area. Duarte's cousin Manuel Diez became Vice President of the country and helped shelter his kinsman. Duarte's family was known to produce candles, this was a major retail and wholesale product since light bulbs for lighting had not been invented yet. While not luxuriously rich an income was available for the Duarte's. Juan Pablo being a man of action as well of a high level of curiosity went off to live in the Venezuela, there he had some contacts and he made off to meet with them. The Venezuela of this period was wracked by a series of civil wars and internal dissensions. Duarte even though he and his family were already by this time residents of the country, still felt ambivalent about openly participating in the country's political life, all this despite the fact that the aforementioned cousin Manuel Antonio Díez from the Vice Presidency, went on to become President of Venezuela in an Ad Tempore capacity.

Duarte travels in Venezuela involved studying the indigenous people's and learning from the black and mulatto communities as well as observing as much as he could of the Venezuela of his time. Duarte was an extremely educated man, fluent in many languages, he was a former soldier and teacher. These abilities helped him survive and thrive in those places he travelled. It also marked him as an outsider, since he came from a caribbean country he probably sounded much different than most of the Spanish speakers around him. However Santo Domingo and the Republic that he had helped father were also highly likely always close to his heart and his mind. So he was very much a man divided, excited and deeply moved by the current surroundings, people's and events around him, however very much thinking about his beloved land and people whom he sacrificed so much for. A man in a contemplative mood, wounded by the drastic expulsion such as he suffered, would have very little time for a long term wife, children or true stability.

Duarte, then living in Venezuela, was made the Dominican Consul and provided with a pension to honor him for his sacrifice. But even this after some time was not honored and he lost commission and pension. He, Juan Pablo Duarte, the poet, philosopher, writer, actor, soldier, general, dreamer and hero died nobly in Caracas[1] at the age of 63. His remains were transferred to Dominican soil in 1884—ironically, by president and dictator Ulises Heureaux, and given a proper burial with full honors. He is entombed in a beautiful mausoleum, the Altar de la Patria, at the Count's Gate (Puerta del Conde), alongside Sanchez and Mella, who at that spot fired the rifle shot that propelled them into legend.

Legacy and honors

- Duarte's birth is commemorated by Dominicans every January 26.

- A memorial to Duarte stands in Roger Williams Park in Providence, Rhode Island[13]

- Broad St. in Providence, Rhode Island co-named Juan Pablo Duarte Boulevard

- A bronze statue to Duarte was erected at the intersection of 6th Avenue and Canal Street in New York City in 1978.[14]

- St. Nicholas Avenue in Manhattan is co-named Juan Pablo Duarte Boulevard from Amsterdam Avenue and West 162nd Street to the intersection of West 193rd Street and Fort George Hill.[15]

See also

Notes

- His paternal grandparents were Manuel Duarte Jiménez and Ana María Rodríguez de Tapia, both from Vejer de la Frontera (Kingdom of Seville, Spain). His maternal grandparents were Antonio Díez Baillo, from Osorno la Mayor (Province of Toro, Spain), and Rufina Jiménez Benítez, who was born in El Seybo (Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, New Spain).[5]

References

- "Juan Pablo Duarte Biography". Biography.com. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-09-11. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- "Biografia de Juan Pablo Duarte".

- Serra, José María (1887). Apuntes para la historia de los trinitarios. Santo Domingo: Imprenta García Hermanos.

- Mendez Mendez, Serafin (2003). "Juan Pablo Duarte". Notable Caribbeans and Caribbean Americans: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 148. ISBN 0313314438.

- González Hernández, Julio Amable (23 October 2015). "Los ancestros de Juan Pablo" (in Spanish).

- www.colonialzone-dr.com

- Deive, Carlos Esteban (1989). Las emigraciones Dominicanas a Cuba, 1795-1808. Santo Domingo: Fundación Cultural Dominicana.

- "Hispaniola Article". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- "Dominican Republic 2014". Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Lora Hugi, Quisqueya. "El sonido de la libertad".

- Mackenzie, Charles (1830). Notes on Haiti made during a residence in that republic. London: Henry Coleburn and Richard Bentley. p. 235.

- "Venezuela tiene deuda histórica con Haití".

- "Historic Figure: Juan Pablo Duarte - Providence, RI". Photo-Ops. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- "Duarte Square". NYC Parks. NYC Parks Department. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- "Mayor Giuliani Signs Bill That Names Section of St. Nicholas Avenue in Honor of Juan Pablo Duarte" (Press release). New York City Mayor's Office. February 22, 2000. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

External links

- Haggerty, Richard A., ed. (1989). Dominican Republic: A country study. Federal Research Division. Haiti and Santo Domingo.