Juma Butabika

Juma Ali Oka Rokoni,[lower-alpha 3] commonly referred to as Juma Butabika, (died April 1979)[lower-alpha 1] was a Ugandan military officer who served as Uganda Army (UA) top commander during the dictatorship of Idi Amin. Despite being notorious for his erratic behavior and abuse of power, he was highly influential, held important army commands, and served as long-time chairman of the Ugandan Military Tribunal, a military court used by Amin to try and eliminate political dissidents and rivals. By commanding an unauthorized attack on Tanzania in October 1978, Butabika was responsible for the outbreak of the Uganda–Tanzania War which ultimately resulted in his death in combat, probably during or shortly before the Fall of Kampala.

Juma Butabika | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Juma Ali Oka Rokoni |

| Nickname(s) | "Butabika" ("crazy"; "the mad one")[1] |

| Died | April 1979[lower-alpha 1] Kampala |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Uganda Army (UA) |

| Years of service | ?–1979 |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel[lower-alpha 2] |

| Commands held | Chui Battalion Malire Battalion |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations | Idi Amin (first cousin once removed) |

| Other work | Chairman of the Ugandan Military Tribunal |

Biography

Early life and 1971 coup

Born as Juma Ali Oka Rokoni,[8] Butabika was of Nubian–Kakwa descent,[4][9][10] and a grandson of Kakwa paramount chief Sultan Ali Kenyi Dada as well as the cousin of Idi Amin's father.[4] Having completed only a few years of primary education,[11] he was reportedly illiterate.[6][12]

At some point, Butabika joined the Uganda Army, and rose to second lieutenant during the rule of Milton Obote.[13] Over time, dissatisfaction grew among parts in the military about Obote's government, resulting in a conspiracy to remove him from power.[4] Butabika joined the conspirators, and their coup was planned at his house. The initial plan was to blow up Obote's plane at the Entebbe International Airport on 24 January 1971, but Butabika's wife informed her brother-in-law Ahmad Oduka, Senior Superintendent of Police, of the plot. He was supposed to be among those on the plane, and his sister-in-law urged him to stay at home on that day to save his life. Oduka, however, was loyal to the government and informed Minister of Internal Affairs Basil Kiiza Bataringaya. Though the assassination of Obote was prevented, the putschists still managed to launch a coup d'état on 25 January 1971. They overthrew the government,[13] but then became unsure about the further course of action. Amin was initially reluctant to assume the presidency, whereupon Butabika reportedly threatened him at gunpoint to accept his appointment as President of Uganda.[4] Meanwhile, Butabika's wife had fled the capital out of fear that her informing Oduka of the putschists' plan would have repercussions.[13]

Soon after the coup, Butabika was involved in the kidnapping and murder of two United States citizens around July 1971, namely journalist Nicholas Stroh and Makerere University lecturer Robert Siedle. The two had tried to gather information on unrest and mutinies that had broken out among some Ugandan military units as result of Amin's seizure of power.[14][15]

Abuse of power and army commands

Gordon Wavamunno's description of Butabika[16]

Butabika became one of leading military figures under the new regime.[2] Despite this, he was widely considered insane in Uganda, even by his own colleagues in the military.[6] He was notorious for his eccentric,[17] "erratic"[18] and excessive behavior, including extreme brutality.[19] According to George Ivan Smith, Butabika believed himself to be a "demi-god" as the government allowed him to kill and torture at will,[5] while Peter Jeremy Allen described him as "merciless psychopathic killer" of "low mentality".[6] Similarly, businessman Gordon Wavamunno had a very negative opinion of Butabika, and regarded him as one of those who "were intoxicated with unlimited and irresponsible power, and did not hesitate to abuse it at the slightest opportunity or excuse."[20] The nickname by which he is best known stemmed from his extreme behavior: "Butabika" is the name of a prominent psychiatric clinic near Kampala,[5][17][21] and a byword for people with a mental illness in Uganda.[5][6]

Promoted to lieutenant colonel,[lower-alpha 2] Butabika served as commander of "elite" units that were regarded as especially loyal to Amin, including the Chui Battalion[17] and the Malire Battalion.[25][10][26] As time went on, elements in the military grew dissatisfied with Amin's regime. Brigadier Charles Arube was among those who felt sidelined, and organised a meeting of high-ranking commanders in March 1974. Butabika was present, and offered Arube his help in cases where he felt ignored by the president.[25] Soon after, Arube attempted to oust Amin in a coup d'état known as "Arube uprising". The Malire Battalion mutinied and joined the coup, but Butabika stayed loyal to Amin.[27] In the end, Arube's coup failed.[25][27]

The Military Tribunal

Despite his extremely limited education, Butabika was also appointed as chairman of the "Military Tribunal" in 1973.[11][21] The Military Tribunal had been set up by Amin to circumvent regular courts and enforce his decisions;[28] it thus had the reputation to "rubber-stamp[ ] Amin's death sentences".[10] According to Amnesty International, the tribunals Butabika chaired were de facto kangaroo courts and passed judgements without regard to laws or proper procedure.[11] He often improvised sentences on the spot.[29] Most prominently, he acquitted several senior military figures who were accused of involvement in the forced disappearance of 18 prominent Ugandans.[14] In contrast, Butabika passed extremely harsh judgements where opponents to the regime were concerned, earning a reputation as "one of Amin's chief executioners".[6] One Ugandan dissident noted that the Lieutenant Colonel's tribunals generally resulted in the death of the accused; they were either executed or released, only to be rounded up and murdered by Uganda's secret service, the State Research Bureau.[7]

Butabika chaired several prominent tribunals, such as when he sentenced British author Denis Hills to death in 1975 for calling Amin a "village tyrant".[15][30] Two years later, he chaired the tribunal that sentenced 12 men to death for conspiring to murder Amin;[31] this trial in particular was described as "travesty of justice, a 'show', since the conventions and pleas of guilt were obtained by force from the accused".[28] He did, however, acquit Wod Okello Lawoko, senior manager of Radio Uganda, after the latter had fallen out of favor with Amin and been arrested on charges of treason.[12] Though Butabika was once dismissed as chairman on one tribunal for misconduct, namely corruption in late 1976, he was later reinstated.[11]

Uganda–Tanzania War and death

By 1978, hostilities had greatly increased between Uganda and the neighboring state of Tanzania, with reports surfacing of invasion plans by the Tanzania People's Defence Force. Butabika was among the proponents of a preemptive strike against Tanzania,[32][33] even though several other leading Ugandan officers believed that their military was not ready for a conflict with Tanzania.[23] The situation escalated on 9 October 1978,[26] when an altercation broke out between a Ugandan soldier and Tanzanian border guards. One of Amin's close advisors, Colonel Abdu Kisuule, later claimed that the entire incident had been orchestrated by Butabika to gain "favors and cheap popularity" from the president.[23][22] According to this version, the Ugandan soldier who caused the altercation had been Butabika's brother-in-law, and his death in a shootout with Tanzanians caused Butabika to seek revenge.[18][23] Others however report that the exact identity of the Ugandan soldier remains unknown, and that Butabika was lied to by his subordinates about the course of events; in that case, it is possible that he actually believed that Tanzanian border guards had initiated hostilities.[26][32]

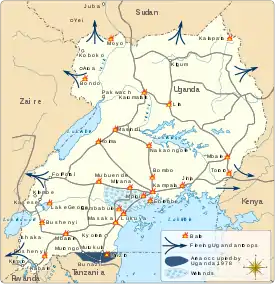

In any case, Butabika consequently ordered an unauthorized attack on Tanzania, resulting in the outbreak of the Uganda–Tanzania War.[22][1] His forces easily overran the Tanzanian troops stationed at Mutukula and Minziro, whereupon he telephoned Amin, claiming that Tanzania had launched an attack and that he had responded with a counter-attack. The president had already been eager to annex Tanzanian territory, and allowed the invasion to proceed. Reinforced by other UA detachments, Butabika occupied the entire Kagera salient (northern Kagera Region) until stopping at Kyaka Bridge, which was destroyed. The UA troops proceeded to celebrate while looting, raping and murdering in the occupied area.[26][32][23]

The Tanzanian military quickly regrouped, causing the UA to retreat back into Uganda even as President Amin declared Kagera's annexation.[23] The Tanzanians launched a large counter-offensive, and the Ugandan military soon started to disintegrate under the onslaught.[8][2] By the time the Ugandan border town Mutukula fell to the Tanzanian army in January 1979, Butabika was back in Kampala and prepared the celebrations for the 8th anniversary of Amin's rule. The lieutenant colonel took part in a parade at Kololo on 25 January, where he and other high-ranking commanders performed a traditional Nubian dance. One Ugandan later commented that when he saw the dancing officers on live television, he realised that his country's leadership "did not know what exactly was going on" in regard to the war.[33] Butabika died in combat during the later stages of the war, though it is disputed when and where he was killed.[2][3] According to an article by the Ugandan newspaper Daily Monitor, he died during the Fall of Kampala. On 10 April 1979, the Tanzanian forces and their UNLF allies entered the city, encountering only light resistance. Butabika was reportedly one of the few leading Ugandan commanders who stayed in the city, and was killed in a firefight with Tanzanian soldiers of the 205th and 208th Brigades in the Bwaise-Kawempe area as they attempted to secure the northern section of the city on 11 April.[2] In contrast, Tanzanian journalist Baldwin Mzirai wrote in his 1980 account of the war, Kuzama kwa Idi Amin, that Butabika was killed at a Tanzanian roadblock on the Bombo road on 7 April 1979.[3][lower-alpha 4]

Personal life

Butabika was a Muslim,[9][10] though he also believed in magic.[23] One observer described him as "short and small [...] bully" who enjoyed challenging "far more strongly-built men" for fights.[10] He was married to a Ugandan woman of the Baziba tribe.[18]

Notes

- According to the Daily Monitor, he was shot on 11 April 1979 in Kampala,[2] whereas Mzirai reported that he died on the Bombo road on 7 April 1979.[3]

- Though most sources report that Butabika was lieutenant colonel during Amin's dictatorship,[8][17] others, including Colonel Abdu Kisuule, have stated that he was a general.[22][23] The Ugandan newspaper The Independent claimed that he was lieutenant general by late 1978.[1] Either way, promotions "were issued randomly" under Amin's regime and mattered little compared to one's direct connection to the president.[24]

- He is also known as Juma Rakoni,[4] Juma Ali,[5][6][7] and Juma Oka Mafali.[2][1]

- In contrast, Thomas Lowman claimed that Butabika survived the war and fled to Sudan.[34]

References

Citations

- "How 'unity' died in Uganda". The Independent (Kampala). 8 April 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- "How Mbarara, Kampala fell to Tanzanian army". Daily Monitor. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Mzirai 1980, p. 97.

- "Idi Amin's son relives his father's years at the helm". Daily Monitor. 13 April 2013. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Smith (1980), p. 120.

- Allen (1987), p. 129.

- Seftel 2010, p. 203.

- "Aspects of Amin's life that you missed". New Vision. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Smith (1980), p. 131.

- Kato (1989), p. 106.

- Amnesty International (1978), pp. 4, ERRATA.

- Kalungi Kabuye (4 October 2012). "The real Idi Amin". New Vision. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- Rashid Oduka; Ali Oduka (14 October 2012). "Saving president Obote". The Independent. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Amnesty International (1978), pp. 15–16.

- Denis Hills (7 September 1975). "THE JAILER AS SEEN BY HIS EXPRISONER". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Wavamunno (2000), p. 161.

- Frederick Golooba-Mutebi (4 April 2011). "Elite troops turn paper tigers again as Gaddafi's Touaregs melt into the sands". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "30 years after the fall of Amin, causes of 1979 war revealed". Daily Monitor. 11 April 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Alan Tacca (11 August 2013). "The ideological direction of NRM MPs is fascism". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Wavamunno (2000), p. 160.

- Otunnu (2016), pp. 292–293.

- Cooper & Fontanellaz (2015), p. 24.

- Henry Lubega (30 May 2014). "Amin's former top soldier reveals why TPDF won". The Citizen. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Cooper & Fontanellaz (2015), p. 61.

- "Brig Arube's failed coup plan". Daily Monitor. 24 October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Pilot Omita parachutes out of burning MiG-21". Daily Monitor. 9 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Mwakikagile (2012), pp. 57–58.

- Ellett (2013), p. 78.

- Lowman 2020, p. 152.

- Keesing's Record (1975), p. 2.

- Seftel 2010, p. 191.

- Mwakikagile (2010), p. 319.

- "Lies drove Amin to strike Tanzania". Daily Monitor. 25 November 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Lowman 2020, p. 185.

Works cited

- Allen, Peter Jeremy (1987). Days of judgment: a judge in Idi Amin's Uganda. Kimber. ISBN 978-0718306373.

- Cooper, Tom; Fontanellaz, Adrien (2015). Wars and Insurgencies of Uganda 1971–1994. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910294-55-0.

- "B. UGANDA" (PDF). Keesing's Record of World Events. 21. August 1975.

- Ellett, Rachel (2013). Pathways to Judicial Power in Transitional States: Perspectives from African Courts. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Human Rights in Uganda Report (PDF). London: Amnesty International. June 1978.

- Kato, Wycliffe (1989). Escape from Idi Amin's slaughterhouse. Quartet Books. ISBN 978-0704327061.

- Lowman, Thomas James (2020). Beyond Idi Amin: Causes and Drivers of Political Violence in Uganda, 1971-1979 (PDF) (PhD). Durham University. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2010). Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era (5th ed.). Pretoria, Dar es Salaam: New Africa Press. ISBN 0-9802534-1-1.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2012). Obote to Museveni: Political Transformation in Uganda Since Independence. Dar es Salaam: New Africa Press. ISBN 978-9987-16-037-2.

- Mzirai, Baldwin (1980). Kuzama kwa Idi Amin (in Swahili). Dar es Salaam: Publicity International. OCLC 9084117.

- Otunnu, Ogenga (2016). Crisis of Legitimacy and Political Violence in Uganda, 1890 to 1979. Chicago: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-33155-3.

- Seftel, Adam, ed. (2010) [1st pub. 1994]. Uganda: The Bloodstained Pearl of Africa and Its Struggle for Peace. From the Pages of Drum. Kampala: Fountain Publishers. ISBN 978-9970-02-036-2.

- Smith, George Ivan (1980). Ghosts of Kampala. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0060140274.

- Wavamunno, Gordon Babala Kasibante (2000). Gordon B.K. Wavamunno: The Story of an African Entrepreneur. Kampala: Wavah Books. OCLC 46969423.