K*bot World Championships

K*bots are moving models made from K'Nex Construction kits, built to participate in specific events run by the K*bot World Championships (USA) and K*bots UK (UK).[1] Events are open to children aged 7–16 years and focus on competitive design and engineering challenges.[2] The K*bot World Championships are an annual event in which students from around the World compete to be crowned World Champion across four distinct categories, called divisions, which are explained in detail below.

K*bots events are currently run in the United States and the United Kingdom. Students come together for an event lasting anywhere from two to five days, during which they are guided through a range of simple engineering concepts in a workshop environment, with all students building one or more K*bots for competitive demonstration on the final day. The K*bot World Championships are the ultimate destination for successful builders, at which students compete against each other in each of the divisions.

History

K*bots in America

K*bots were invented by Thomas Vermersch,[2] a former science educator from Texas, in the summer of 1998 at the San Antonio Academy during a holiday Science Camp. During a roller-coaster building session one afternoon, two of his students made simple motorised machines from K'Nex parts and placed them opposite each other on the floor, determining that they must try to push each other back to win their match. Mr. Vermersch saw potential with this idea. The following year he held a K*bots competition for the first time, using a development of these rules which saw K*bots running on a tabletop, as a discrete event which is credited as being the start of K*bots.[1]

In 1999, K*bots in America became more structured with the crystallisation of competition into Division 1 (two-wheel drive) and Division 2 (four-wheel drive). In 2002, a remote control Division 3 was added to the event roster to make use of Cyber K'Nex units. 2002 also saw the first World Championships, which featured solely American competitors in its inaugural year.

From its initial base competitions in Texas and Nevada, K*bots expanded in 2005-06 to include new regional events in the city of North Las Vegas and two regional competitions in Phoenix, Arizona. The number of events then shifted in 2007, with Texas losing its regional events before Phoenix shut down in 2009. However, there is currently a fresh movement abound to restore K*bot events to states outside of Nevada.

K*bots in Britain

The first recorded K*bots were built in Britain in early 2001. A group of students, including K*bots UK founding members Toby Wheeler, David Weston and Chris Bowdon, organised the first collective event in April 2002 in Carterton, near Oxford. The first event featured manually operated K*bots only, which would later come to be termed Division M. In 2003, the UK group ran a second event, at which they trialled the American Division 1 format in addition to their own manual-based competition.

In 2004 the event formally became part of the K*bot World Championships, and started running all four divisions in more structured events. With interest gaining momentum, in 2006 the UK started running Regional competitions of its own around the South of the country, leading to the first UK Championships in 2007, though in truth these only served as a qualifying round for the World Championships themselves.[3]

In 2010, the K*bots In Schools curriculum enrichment programme was launched, allowing pupils to build K*bots for competition during a workshop based at their own school. Successful entries are retained for the annual UK Championships, so that their builders may improve and compete with them during the finals.

K*bot World Championships

.jpg.webp)

By the Autumn of 2001, regional US K*bots events were running in San Antonio (TX), Corpus Christi (TX), Henderson (NV) and Las Vegas (NV). Mr. Vermersch sought a means to allow regional winners to test their K*bots against those from other events, and devised the K*bot World Championships to allow students from across all regions to come together and compete for trophies in each of Division 1, 2 and 3. The first World Championships were held in July 2002 in Las Vegas, Nevada, at the Veterans Memorial Leisure Services Centre, which has become their permanent home ever since.

In 2003, the World Championships returned as a far larger and more prestigious event. Considerable expense went into trophies and prizes for the winning students and it started to attract interest from regional television and press media.[4] The 2003 event also saw Toby Wheeler from the UK group make an appearance for the first time. During the course of the week, it was agreed that UK events would henceforth adopt the same format as K*bot events in America, with a view to becoming an official part of the World Championships in 2004.

Expansion

2004 accordingly saw the World Championships expand to feature students from outside America. Britain sent their first representative to the World Championships, and in addition there were students representing Japan, Austria and the Philippines, as well as several states of America itself.[2]

2004 was also the first year to feature the British-style manual K*bots, re-branded as Division M (for manual), raising the number of divisions at the World Championships to four in total. However, it incredibly took until 2008 for a British student to actually win a World Championship in the Division conceived on British soil.[5]

With enthusiasm for K*bots gathering pace and returning students becoming ever more inventive, the 2005 World Championships saw the emergence of some very advanced models which started, for the first time, to push the limits of what the K'Nex motors were capable of. The Division 1 World Championship Final, widely regarded as the best K*bot match of all time, involved so much pressure on the materials that damage was caused to both the K'Nex pieces and the motors powering the K*bots.

This prompted a re-drafting of the rulebook in 2006, to allow technology to advance in a more sustainable fashion. The format has remained largely unchanged since that time, though rules have been tweaked in reaction to new technologies.[6] The K*bot World Championships today remain a proving ground for the best young engineering minds from around the World, and are looking to expand even further over the coming years.

Rules and regulations

Note that the following guidelines are only an outline of the rules of K*bots, and are not exhaustive. A full, detailed set of rules and regulations for the K*bot World Championships can be found on the official website, kbotworld.com

Division 1 and 2

Competition regulations

Division 1 and 2 K*bots are motorised models placed at opposite ends of the competition table and switched on. The aim is to push your opponent's K*bot off the table within a 90-second time limit. If both K*bots remain on the table after 90 seconds, the winner will be the K*bot which has advanced furthest towards or past the centre line on the competition table.[7]

A K*bot is considered eliminated as soon as any of its wheels are fully off the table. K*bots can also be eliminated if they are flipped completely over during a match, in such a way that they are unable to continue to move independently.

If the two K*bots have locked together and are not moving, after 45 seconds the referee can tap the table by lifting and dropping each end of the competition table in sequence, until the K*bots start moving again.

Build regulations

K*bots can weigh no more than 1.3 kg (2.9 lb) and are limited by their size. In American and World Championship events, the maximum permitted dimensions are length 60 cm (24 in) × width 45 cm (18 in) × height 35 cm (14 in). In British events, the maximum permitted dimensions are length 50 cm (20 in) × width 35 cm (14 in) × height 35 cm (14 in).

K*bots are permitted a maximum of four medium-size K'Nex wheels, with an optional specialty Alliance Rubber band around each of the wheels to enhance grip. The sole difference between the divisions is that Division 1 K*bots have only two-wheel drive; Division 2 K*bots must have four-wheel drive.

Division 3

Division 3 has undergone huge changes since its initial introduction into the regulations in 2002. It has appeared in a variety of forms, though always making use of remote-control building kits. The format has historically changed on a two-year basis.

- In 2002 and 2003, Division 3 K*bots were constructed using Cyber K'Nex, and ran to similar competition rules to those used in Division 1 and 2.

- In 2004 and 2005, the K'Nex Ravage infra-red control units were used. K*bots competed for the first time in a tabletop arena enclosed within plexiglas walls, and scored points for their attacks and damage, similar in concept to the Robot Wars TV shows.

- In 2006 and 2007, Division 3 reverted to a test of pushing power, using programmable computerised motor units. These powerful 2-channel motors allowed for some fearsome weaponry and fast-paced matches, but the software accompanying the units was ultimately unreliable and led to their demise.

- In 2008 and 2009, the Ravage units were revived as the tabletop arena returned, but with a slightly different format. Emphasis was placed on building an active weapon, as well as building in multi-directional movement, which presented a challenge on only two channels.

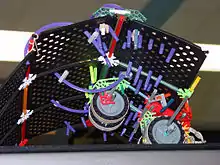

- Since 2010, Division 3 has evolved to make use of custom-made radio control units with 3 channels, built specifically for K*bot competitions. The control hardware consists of a 'black box' battery unit, containing the radio receivers and a 7.2v lithium battery, and three K'Nex motors (two powering the drive, and one powering an active weapon). K*bots continue to do battle in a tabletop arena with Plexiglas walls.

Division M

Competition regulations

Division M K*bots are manually operated models which compete in a tabletop arena enclosed within plexiglas walls approximately 7.5 cm (3.0 in) tall. There are strict rules of engagement, the most important being that a K*bot must be pushed and released to initiate movement; a K*bot cannot be moved or turned directly by hand.

K*bots score points for attacks with an active weapon (e.g. a flipper, hammer or rotary disc) and damage caused to an opponent's K*bot. Operators may also lose penalty points for infringements of the operation regulations. The K*bot amassing the most points during a 90-second match is adjudged to be the winner. If both K*bots are tied for points after 90 seconds, they will enter a short overtime shootout in which the first K*bot to score a point is the winner.

If a K*bot leaves the tabletop arena at any point during the match, it is automatically eliminated. Indeed, some students have developed one-hit-kill weapons designed to achieve exactly this.

Build regulations

K*bots must weigh between 450 g (0.99 lb) and 650 g (1.43 lb) and are subject to the same size restrictions as for Division 1 and 2 K*bots (see above). Builders are permitted more creative freedom within this Division, since the range of chassis and mobility types are not restricted.

All moving mechanisms on a K*bot must be mounted on a pivot, or be as a result of movement around or through a fixed point. This includes active weapons, which are generally considered flipper-type and hammer-type weapons. There is currently no provision for spinning disc-type weapons. Moving mechanisms must be operated by a handle or lever; the shafts cannot be directly operated by hand.

Previous regulations

Before K*bots in the United Kingdom became an official part of the K*bot World Championships, there were two build categories of manual K*bots. Division M1 was for lightweight K*bots weighing a maximum of 75 g (0.165 lb), designed to encourage students to build at home if they did not own a lot of K'Nex. Division M2 was a more standard category, with a weight limit of 500 g (1.1 lb).

These split categories survived until early 2004, but with the growth of more structured K*bots events in Britain, they became obsolete when the standard World Championships weight limit was adopted.

Other categories

During an event at Marling School of Engineering in February 2010, British students began testing a proposed K*bot Division, run to the same rules as Division 1 or 2 with the sole exception that no wheels were permitted anywhere on the design. Pupils instead had to build entries with tracks, legs or other forms of alternative mobility. The first event was won by a K*bot named Jimbot, but the category has since been deemed unsuitable for younger builders and has therefore been shelved.

While the four K*bot divisions comprise the vast majority of build time during an event, there is often opportunity for special team-based challenges, particularly at events in the United Kingdom. These special challenges focus on a specific design skill, and allow students to work collaboratively to devise the most effective solution.

Prior examples include wind-powered sail cars, pull-back dragsters, tennis ball launchers and motorised walking racers. One event in America even saw the creation of a vast interactive skyscraper, with moving elevators and other features. Build regulations and success criteria for the challenges are usually set on an ad hoc basis, though each new challenge sets a precedent for future repeats. The four K*bot divisions are the focal point of the week, but in British events at least, the special challenges are often the most memorable and stimulating activities of the workshop.

Format

Regional events

Each year, a number of Regional events are held in preparation for the World Championships.[8] Regional events are week-long workshops at which students can prepare and test their K*bots for competition. At these events, first-time builders receive extensive support to get them started with their first K*bot. Under guidance from the instructors, first-time students learn basic concepts of physics and mechanical engineering, specific to building an effective moving model out of K'Nex.

At the end of each Regional event, a competition is held to determine the most successful builders in each division throughout the week. Winning a Regional event is therefore an indication of a builder's ability, but Regional Champions do not receive the trophies and major prizes which are available for winning a World Championship.

Participation at a Regional event is not mandatory for students wishing to take part in the World Championships, but it is highly recommended for a number of reasons. Most importantly, first-time builders receive only limited instruction time at the World Championships, whereas provision is much greater at Regional events. Additionally, students benefit from the extra testing and preparation time during the Regional event; World Champions are almost always veterans of the Regional events, with very few historical exceptions.

World Championships

In 2009, the World Championships underwent landmark changes to make the events more structured, with tweaks made for 2010 to improve the show even more. The contests are run over five days, Monday to Friday, in mid-July.

During the first four days, students have the chance to assess the opposition, and make any changes necessary to their K*bots to give them further competitive advantage. This will be the first opportunity that many students will get to meet other Regional qualifiers.[1]

Also during the first four days, K*bots will compete in official Qualifying sessions which count towards a seeding system for the final day's competitions. In these sessions, students are permitted a maximum of six official Qualifying matches (three per session in two sessions during the week), in which they are awarded points for performance. In Division 3 and M, these simply correspond to the number of points accrued during the match. In Division 1 and 2, K*bots are drawn into a ladder system, and builders must challenge opponents above them in order to climb higher. K*bots take the place of those they defeat, with intermediary K*bots each dropping one place in the ladder.

The top eight qualifiers in each division are seeded for the final competition. This means that they are kept separate from each other in the early rounds, and cannot meet other seeded K*bots until at least the Third Round. In the event of an uneven number of K*bots being entered into the draw, the top seed(s) will receive a first-round bye.

The World Championship Finals in Division M are held on the afternoon of the fourth day, for timing reasons. On the fifth day, the World Championship Finals are held for Division 1 (widely regarded as the most exciting of the four),[1] Division 2 and Division 3. Parents are invited to watch the Finals and support participating students.

The draw

The World Championship Finals are run as a series of knockout rounds. Divisions are generally open to a maximum of 32 registered entrants (although Division 1 and 2 regularly extend to 40 students), and are run to the following format:-

- Preliminary Round (explained below)

- First Round – 32 students take part, 16 winners

- Second Round – 16 students take part, 8 winners

- Third Round – 8 students take part, 4 winners

- Semi-Finals – 4 students take part, 2 winners

- Grand Final – 2 students take part, winner is crowned World Champion

In the event of more than 32 students being registered for a Division, the students finishing lowest in the official Qualifying sessions must take part in a Preliminary Round, in which they play each other in a knockout structure, to reduce the total number of students to 32.

Previous winners

World Championship winners

Division 1 World Championships

| Year | Winner | K*bot | From | Runner-up | K*bot | From | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | The Greem Reaper | Corpus Christi, TX | Red Alert | San Antonio, TX | |||

| 2003 | The Wall | Phoenix, AZ | Clean Sweep | Palm Springs, CA | |||

| 2004 | Snow Plow | Palm Springs, CA | Gear | Stoneham, MA | |||

| 2005 | The Greem Reaper | Corpus Christi, TX | Snow Plow | Palm Springs, CA | |||

| 2006 | Deadbolt | San Antonio, TX | Crusher Junior | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2007 | Mini-Moo 3 | Henderson, NV | Revenge of the Bug | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2008 | Blackout | Stoneham, MA | Wheels Of Steel | Cheltenham, ENG | |||

| 2009 | Pipsqueak | Las Vegas, NV | The Ramp | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2010 | Destiny | Cookley, ENG | The Ramp | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2011 | TBC | Las Vegas, NV | Dream Killer | Henderson, NV | |||

| 2012 | Party Monster 12 | Las Vegas, NV | K*bot Crusher | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2013 | Child's Play | Beijing, CHN | Hero | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2014 | Zer0 | Las Vegas, NV | Man-Handler | Las Vegas, NV |

Division 2 World Championships

| Year | Winner | K*bot | From | Runner-up | K*bot | From | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Tank | Las Vegas, NV | Godzilla | San Antonio, TX | |||

| 2003 | Tank | Las Vegas, NV | The Goalie | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2004 | Crosshair | Alloa, SCO | Smoken 45 | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2005 | Man Eater | Corpus Christi, TX | Lawless | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2006 | Man Eater | Corpus Christi, TX | Bad Haircut | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2007 | Man Eater | Corpus Christi, TX | Crosshair | Alloa, SCO | |||

| 2008 | Lotus | Phoenix, AZ | Yin Yang | Stoneham, MA | |||

| 2009 | Mohawk | Las Vegas, NV | Corpus Christi Hurricane | Corpus Christi, TX | |||

| 2010 | Genesis | Henderson, NV | Tidal Wave | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2011 | Static 3.0 | Las Vegas, NV | <Unknown> | <Unknown> | |||

| 2012 | Static 3.0 | Las Vegas, NV | Red Tiger | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2013 | Ronin | Las Vegas, NV | Yellow Menace | Oxford, ENG | |||

| 2014 | Bulldozer | Henderson, NV | Jarod | Las Vegas, NV |

Division 3 World Championships

| Year | Winner | K*bot | From | Runner-up | K*bot | From | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | Texas Tornado | Corpus Christi, TX | The Thing | San Antonio, TX | |||

| 2003 | Flyswatter | San Antonio, TX | The Winner | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2004 | Wrath | Corpus Christi, TX | Texas Tornado | Corpus Christi, TX | |||

| 2005 | Wrath | Corpus Christi, TX | Rampanator | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2006 | Black Hole | Bangkok, THI | Gladiator | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2007 | Slicer | Henderson, NV | Purple Beauty | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2008 | Hazard | Phoenix, AZ | Crazy Frog 3 | Alloa, SCO | |||

| 2009 | Hydraulic | Stoneham, MA | Mouse | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2010 | Gladiator | Las Vegas, NV | <No Name> | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2011 | Gladiator | Las Vegas, NV | <No Name> | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2012 | Chi | Las Vegas, NV | Bridgeigator | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2013 | Pipsqueak's Revenge | Las Vegas, NV | Alice | Lancaster, CA | |||

| 2014 | Masher | Las Vegas, NV | The Fighter | Honolulu, HI |

- Note: In 2005, Edy Valdes operated Wrath, the K*bot built by Oliver Serrao, and dedicated his World Championship to him posthumously.[9]

Division M World Championships

| Year | Winner | K*bot | From | Runner-up | K*bot | From | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Ripper | San Antonio, TX | Flipper 2 | Tokyo, JAP | |||

| 2005 | C4 | Palm Springs, CA | Tomahawk | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2006 | C4 | Palm Springs, CA | KAKO | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2007 | Reaper | Henderson, NV | Double Attack | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2008 | Orbit | Cheltenham, ENG | Whiplash | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2009 | Long Shot | Henderson, NV | Mini-Man Jr. | Sicily, ITA | |||

| 2010 | Check M8 | Henderson, NV | Duffbot | Las Vegas, NV | |||

| 2011 | Check M8 | Henderson, NV | Meta-Turtle | Cookley, ENG | |||

| 2012 | Smile As You Kill | Las Vegas, NV | Thor | Beijing, CHN | |||

| 2013 | One Too Many | Beijing, CHN | Cosmic | Los Angeles, CA | |||

| 2014 | Check M9 | Las Vegas, NV | Dark Matter | Los Angeles, CA |

Details of the 2009 World Championship winners can also be found online at Centennial View

UK K*bots In Schools winners

Key Stage 2 UK Championships

| Year | Winner | K*bot | School | Runner-up | K*bot | School | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Fiddlesticks | Cookley, ENG | Wheels Of Steel | Cheltenham, ENG | |||

| 2011 | Hawkeye | Franche Community Primary School | Terminator | Hatch Ride Primary School

Gorse Ride Junior School | |||

| 2013 | Crusher Upper | Hatch Ride Primary School | Shredder | Finchampstead Primary School | |||

| 2014 | <Unknown> | St. Sebastian's Primary School | Hazard | Nine Mile Ride Primary School |

Key Stage 3 UK Championships

| Year | Winner | K*bot | School | Runner-up | K*bot | School | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | The Incredible Bulk | Cookley, ENG | Crosshair | Alloa, SCO | |||

| 2011 | Yellow Menace | Oxfordshire Home Education Group, Lord Williams's School, ENG | The Incredible Bulk | Cookley, ENG |

- Note: There has been no Key Stage 3 competition since 2011.

Key technologies

Throughout the history of K*bots, enterprising students have sought creative ways to gain an advantage over their rivals by developing technologies to improve the power or effectiveness of their K*bot. Working with K'Nex in tandem with advanced principles of mechanical engineering, students have exceeded the remit of K'Nex as merely a toy construction kit. Modern K*bots are complex, finely tuned machines.[2] This section details just a few of the innovative strategies employed at the K*bot World Championships.

Gearing strategies

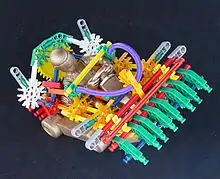

Paramount to an effective Division 1 or 2 K*bot is the use of K'Nex gears to alter the output of the standard K'Nex motor. By attaching a small gear to the drive shaft and meshing it with a larger gear attached to the wheel axle, the motor's output is slowed down, moving it into a lower torque band and improving the traction (and therefore pushing power) of the K*bot. This process can be repeated multiple times to enhance the K*bot's power still further. In America, this process is termed gear reduction.[10] In Britain, it is termed downshifting.

It is also possible to gear the motor the other way, increasing the speed of the motor's output but reducing its overall torque. This strategy is counter-productive in Division 1 or 2, but can be employed to great effect in Division 3 as part of rotating weapons such as rotary axes or spinning discs.

Brakes

Brakes are non-motorised additions to a K*bot which prevent it from being pushed backward. These vary from simple chassis protrusions, designed to snag and dig into the tabletop surface, to more advanced strategies such as slip-gears and backward-mounted friction motors on axles to prevent them from turning backward.

Due to increasing stresses being placed upon K*bots, all varieties of brakes were outlawed from 2006 onwards in an attempt to protect the K'Nex motors from damage.[6] A welcome side-effect of this ruling has been a shift in focus from defensive strategies to offensive strategies; in the absence of brakes, K*bots has become more a test of pushing power, rather than who can resist a push most effectively.

Four-wheel drive

A basic technology but nevertheless very important, four-wheel drive was introduced on K*bots as early as 1999, at the birth of Division 2. Initially it was installed by way of a bevel gear attached to a shaft protruding from the second output port of the K'Nex motor, meshed with a gear on the front axle. However, when downshifting became commonplace at the World Championships circa 2005, this method become obsolete, since a small gear could not reliably be meshed with a larger gear in a bevelled setup.

Division 2 K*bots therefore evolved to have a drive train comprising a series of meshed gears, linking the front and rear wheel axles. This is now accepted as the only feasible method to achieve success in modern-day Division 2.

Variable transmission

Taking gearing strategies to the extent of its logical progression, in 2008 David Small, from Phoenix, Arizona, created the first (and to date, the only) K*bot with a variable transmission system. The K*bot started a match with the motor running in high-speed, low-torque mode. However, when it came into contact with another K*bot, it triggered a mechanism which shifted the transmission to engage with a different drive train, which was low-speed and high-torque.

This allowed the K*bot to reach the centre-line of the competition table before its opponent, and then engage high-torque mode to prevent it from being pushed backward at too great a rate. The efficiency of this system was remarkable, and it won David the 2008 Division 2 World Championship.

Outlawed

However, an objection was raised in August 2008 on the grounds that the introduction of such a complex system into the field would result in such dramatic potential changes to the Division 2 build philosophy that it would prevent many students from producing successful K*bots. The length of time necessary to learn, understand and effect this system would exclude all but the long-term veterans from being able to build such a device on their own K*bots, and would create a two-tier system at the World Championships; the haves and the have-nots.

To stave off this potentially damaging state of affairs, variable transmission was accordingly banned from 2009 onwards.[6] It remains, therefore, an exceptional technological achievement – but one that will never be repeated at the World Championships.

Active chassis

The pioneer of this technique was Edy Valdes from Texas, who installed an active chassis on his K*bot Greem Reaper to win two World Championships in Division 1, in 2002 and 2005. Its effectiveness is based on the twin premises that a K*bot requires pressure over its rear wheels to generate grip, and that, with the right technology, the pushing power of an opposing K*bot can be absorbed and used against it.

Active chassis, more commonly termed flexi-fronts, are non-rigid constructions designed to arch up on contact with an opposing pushing force, creating elastic potential energy, and channelling the resulting pressure into the K*bot's rear wheels.

This phenomenon can be highlighted by using the human body as an example. If you are trying to push a heavy object, doing so with arms fully outstretched is seldom effective. However, if you bend your arms slightly and tense your muscles, it allows you to push against much greater resistance. K*bots work in exactly the same way.

Multi-pivot flippers

Moving into the field of Division M; there are two key types of weapon – flippers and hammers – and both have been subject to significant upgrades since their initial inception. Multi-pivot flippers have been around in Britain since K*bots first began, but did not appear in America until 2005, after students had been exposed to them at the 2004 World Championships.

A conventional flipper is manipulated by simply pushing down on one side of a pivot to generate opposing (upward) movement on the other side. A flipper built with multiple sets of pivots, however, is designed to multiply the force used and distance travelled by the input lever, which results in a significantly more powerful output from the weapon shaft. These flippers are designed to be capable of throwing a 650g K*bot several feet across the competition table, and possibly even clearing the arena walls to win by knockout.

Turret hammers

As if in response to the rising dominance of the flippers, Turret Hammers made a brief appearance at the 2005 World Championships, before positively exploding in number in 2007. In a single year, the multi-pivot flippers were eclipsed by the sheer effectiveness of these new hammer weapons, and they began to pervade the field.

A conventional hammer can only be fired in one direction; namely, whichever direction the K*bot happens to be facing, since adjusting the K*bot's position before firing a weapon is strictly prohibited. However, turret hammers exploit a loophole in the rules which allows users to adjust the positioning of their weaponry before firing. Turret hammers are therefore built on a fully rotating platform atop the K*bot, allowing them to be rotated to face an opponent before the hammer is fired, virtually guaranteeing a hit (and therefore a point) every time an opponent's K*bot comes within striking range.

K*bot Ollie Awards

In 2005, the popular Oliver Serrao, a K*bots student and Division 3 World Champion, tragically lost his life along with his parents in a fire at their home in Texas.[11] This tragedy saddened the K*bots fraternity, as Oliver was not only a likeable young man but also had star potential. In commemoration of his name, the K*bot Ollie Awards were set up to every year honour outstanding K*bots students from the prior year's competition. Each year at the World Championships, the Ollie Awards ceremony is held and trophies are presented to the winners in each category, voted on by the K*bot students and others associated with the World Championships.

Awards categories

Each year, six trophies are given out as the K*bot fraternity honours its top students. These categories are:

- Best New K*bot Design - Awarded for the most innovative and successful K*bot debuted in the previous year.

- K*bot Rookie of the Year - Awarded to a debutant student who achieved a lot at the World Championships.

- K*bot World Championship Match of the Year - Awarded to the two students whose K*bots gave us the most exciting or dramatic match at the previous year's World Championships.

- Most Improved Student of the Year - Awarded to the student who has made the biggest improvement since their last showing at the World Championships.

- K*bot Student Ambassador of the Year - Awarded to a student who has worked hard to promote the spirit of K*bots, both during events and throughout the previous year.

Pro Challenge

Every year, a popular feature of the Ollie Awards ceremony is the Pro Challenge, in which the World Championships instructors all build their own K*bots to compete against each other for a special prize. Since the instructors are able to draw on vast amounts of K*bot building knowledge and are not restrained by the strict letter of the rules for this one-off special event, these Pro Challenge K*bots tend to be amongst the most powerful creations in existence, and matches are always well received by the students and parents who attend the ceremony. There have been four Pro Challenge tournaments to date, with American instructors winning three times and British instructors winning once.

K*bot Hall of Fame

When a K*bot reaches the end of its useful life, the chassis is generally taken apart so that the parts can be recycled. However, if a K*bot has been particularly successful or noteworthy for some reason, it is preserved and retained in the K*bot Hall of Fame, which is displayed every year at the World Championships to provide inspiration for current students. The K*bots inducted into the Hall of Fame so far are:

Godzilla (Division 2)

Built in 1999, this was the first superstar K*bot. Its unbeaten run in regional events which saw it win five regional championships in five years is unlikely ever to be rivalled. Peculiarly, however, Godzilla never delivered on its potential at the World Championships, with its best result being to reach the Grand Final in 2002. Unfortunately, as one of the earliest K*bots to be built before proper documentation of students was effected, the identity of Godzilla's builder is unknown.

Greem Reaper (Division 1)

While it was competing in 2002–2005, this K*bot was the best in the world. It was years ahead of its time in terms of technology and pushing power. Greem Reaper cruised to the 2002 Division 1 World Championship, but was narrowly defeated in 2003 and was then eliminated in the opening round in 2004, to the surprise of everyone involved in the competition. This prompted some upgrades by builder Edy Valdes, and Greem Reaper then returned to win the 2005 World Championship, before retiring the following year.

Wrath (Division 3)

A special K*bot in the hearts of many, this was the creation of Oliver Serrao, after whom the K*bot Ollie Awards are named. It won the 2004 Division 3 World Championship, and when Serrao died in a fire the following year, its operation was taken over by his friend Edy Valdes, who took it to repeat World Championship success in 2005.[9] Valdes dedicated his victory to Serrao posthumously and the K*bot Wrath was retired, becoming the first K*bot in history to go unbeaten at the World Championships.

Project X (Division M)

Though its list of accolades seems short compared to other K*bots in the Hall of Fame, Project X is nevertheless a notable addition as it was the first UK K*bot to win an event in Britain. It is also the blueprint design for the vast majority of contemporary multi-pivot flippers, almost all of which are based on Toby Wheeler's original design. Project X never competed at a World Championships, since its builder was too old at the time it was built.

Crosshair (Division 2)

This made history as the first K*bot built outside the United States to win a K*bot World Championship, when Andrew Martin took the Division 2 crown in 2004.[12] It is also one of the longest-serving K*bots in history, having competed at no less than six World Championships, reaching at least the semi-final stage on four occasions. Crosshair also won two Regional events and a UK Championship, before being retired in 2009.

C4 (Division M)

Designed by Chace Younger from California, C4 was built in reaction to the multi-pivot flippers introduced in the 2004 World Championship, and featured an innovative new take on the design. Younger fitted hammers to the arm of his flipper, which automatically fired whenever the flipper was activated. This meant that, if the flipper failed to overturn an opponent, the hammers would strike and salvage a point. This perfect weapon synergy won C4 back-to-back World Championships in 2005 and 2006. It was retired, unbeaten, when Younger became too old to compete.

Tank (Division 2)

Most famous as the K*bot who repeatedly denied the mighty Godzilla from winning a World Championship, Kyle Young's K*bot won titles in 2002 and 2003, knocking Godzilla out of the competition on both occasions. It was the first to make genuinely effective use of gearing strategies to enhance its pushing power and, though unspectacular, it has always been a solid opponent.

Man Eater (Division 2)

Yet another Division 2 K*bot to achieve fame, Man Eater was the creation of Devyn Bowden from Corpus Christi, Texas. In its four years of competition, Man Eater achieved the incredible feat of winning three successive K*bot World Championships, dominating the division from 2005 to 2007. During this time, it also achieved notoriety in Britain as the nemesis of Crosshair, denying Andrew Martin the title on two successive occasions by knocking him out of the competition.

The Hall of Fame gallery

Oliver Serrao, the young man after whom the Ollie Awards are named, won the 2004 World Championship with Wrath. |

Crosshair is the most successful British K*bot in history and won Britain their first World Championship, in 2004. |

C4, a pioneer in Division M weapon synergy and twice World Champion. It was unbeaten prior to its retirement after the 2006 event. |

Man Eater, built by Deyn Bowden, is the only K*bot to ever win three World Championships in a row, dominating Division 2 from 2005 to 2007. |

References

- kbotworld.com, Official website of the K*bot World Championships.

- Centennial View, 08-11-2009, contains lots of information about the 2009 K*bot World Championships.

- K*bots in the UK, a sub-page of kbotworld.com focusing on British events.

- Las Vegas Review Journal, 15-07-2003, "Elementary Physics" article and photo.

- Gloucestershire Echo 02-08-2008, "Sam shows steel in robot war win", article detailing Sam Steel's 2008 World Championship success.

- kbotworld.com World Championships rulebook, updated June 2011.

- Las Vegas Review Journal, 19-07-2008, "Dueling Robots" article and photo.

- Corpus Christi Caller Times, 26-06-2005, "Kids bring robots to life", a local news feature on the 2005 Corpus Christi Regional Event.

- Corpus Christi Caller Times, 30-07-2005, "The human behind the robot win", detailing Edy Valdes' success in the 2005 World Championships.

- "K*bot Magic", an online design guide for K*bots making use of gearing strategies.

- Ocean Drive Fire Report, detailing the incident in which Oliver lost his life.

- Scottish regional newspaper, August 2004, "World champion constructor", article detailing Andrew Martin's 2004 success.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to K*bot World Championships. |

- kbotworld.com - the official website of the K*bot World Championships, containing a wide range of information, including competition reviews and the official rulebook (pending updates)

- K*bots on YouTube - official World Championship matches on YouTube

- K*bots UK homepage - the commercial website of K*bots UK, who run the K*bots In Schools curricular enrichment programme

- K*bots on Facebook