Kath kuni architecture

Kath-Kuni is an indigenous construction technique prevalent in the isolated hills of northern India, especially in the region of Himachal Pradesh. In Uttarakhand, a similar architectural style is known as Koti Banal (named after the village where during the 1991 Uttarkashi earthquake, the buildings made with traditional architecture largely remained unharmed).[1] It is a traditional technique that uses alternating layers of long thick wooden logs and stone masonry, held in place usually without using mortar. It has been transmitted orally and empirically from one generation to the next, through apprenticeships spanning a number of years.[2] The technique was devised keeping the seismic activity, topography, environment, climate, native materials and cultural landscape in perspective. Most of the oldest temples, in the region, are built using this ancient system. This unique construction technique has led to the formation of a vernacular architectural prototype known as Kath-Kuni (cator and cribbage) architecture.

Materials

The primary building materials employed in the construction are stone (igneous), wood and slate (metamorphic). Stone, usually granite, which is good in compression is used for foundational purposes. The walls are made of stone and wood which are alternatively stacked up, one over another. Wood which is good in compression and tension are interlocked in the corners with other wooden members. Deodar/Kali wood which is commonly available, is used as wall, flooring and roofing members. Slate, is used as a water proofing roofing material, employed to protect the building from heavy rain and snowfall. All the materials are locally available and are easily sourced.

Construction technique

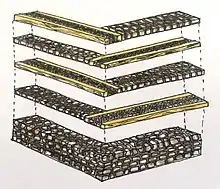

The construction typically involves laying courses whose outer layer comprises random rubble masonry and wood, laid out alternately.[3] The walls are almost two feet thick in dimension and act as a cavity wall. After one course of random rubble there is a course of wood (only outer course), which is interlocked by dovetail random intermediate joints, to hold the wooden members in place. The courses alternate until a ceiling height is attained. The cavity wall of every outer course of wood/stone is filled with smaller stones within. They act as insulation fillers between the outer layers.

Applications

Kath-Kuni Architecture has widely been employed in the construction of residences.[4] Here the farmers would rear their cattle in the lowermost floor such that the heat generated would heat the upper layers of the house. The next level of the dwelling unit is used as a granary, where food is stocked for the winters. The last few floors are designed as residential spaces which are cantilevered from the main walls of the house to capture sunlight, during the day. Hip roofs are usually employed but there are instances where gable with dormer windows are adopted. Good examples of Kath-Kuni Architecture could be seen in existing temples, where the craftmanship exhibited in the form of ornamentation and detailing in design,[5] can be seen on the wooden members of walls, flooring, windows, doors and roofs.

Advantages

- Sustainable

- Materials locally available

- Suitable for seismic zones

- Insulates during extreme weather conditions

- Energy efficient

- Helps sustain the livelihood of people who are mostly farmers or craftsmen

- Employs local crafts and keeps the tradition alive

- Employs unskilled labour

Himachal Pradesh, Temples

Himachal Pradesh, Temples

Disadvantages

- Lack of availability of building materials

- Time-consuming to construct

- Labour

Decline

With urbanization and newer construction materials available in the market, that deliver buildings much faster, the traditional techniques started losing its relevance over time. Also, with rising demand for natural materials, the rapid loss of forest covers resulted in the enforcement of Environment Forest Act that banned the use of any more wood from the forests.

See also

References

- Sengupta, Nirmal (September 29, 2018). Traditional Knowledge in Modern India: Preservation, Promotion, Ethical Access and Benefit Sharing Mechanisms. Springer. ISBN 9788132239222 – via Google Books.

- Khimta, Abha Chauhan (2018-08-29). "Political Participation of Women in Himachal Pradesh in India: Impact on Social Change". International Conference on Future of Women. The International Institute of Knowledge Management-TIIKM: 11–21. doi:10.17501/icfow.2018.1102. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dave, Thakkar, Shah, Bharat, Jay, Mansi (2013). Prathaa. Ahemadabad: SID Research Cell, School of interior design, CEPT University. ISBN 978-8190409681.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Himachal Pradesh". doi:10.1163/1570-6664_iyb_com_state_3150. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Belz, Melissa Malouf (2015-05-28). "The Role of Decorative Features in the Endurance of Vernacular Architecture in Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh, India". Geographical Review. 105 (3): 304–324. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2015.12068.x. ISSN 0016-7428. S2CID 161365249.