Katherine "Kitty" Marshall

Katherine "Kitty" Marshall born Emily Katherine Willoughby (1870–1947) was a British suffragette known for her role in the militant Women's Social and Political Union and as one of the bodyguard for the movement's leaders who had been trained in ju-jitsu.

Katherine "Kitty" Marshall | |

|---|---|

| Born | Emily Katherine Willoughby 1870 |

| Died | 1947 |

| Known for | suffragette and ju-jitsu |

| Movement | WSPU |

| Spouse(s) | Arthur Marshall, solicitor |

Life

Marshall was born Emily Katherine Willoughby in 1870.

Her first marriage was to Hugh Finch, a doctor, the son of a vicar, who had contracted venereal disease in 1899 and passed it to Kitty, and from whom she was divorced in 1901. She then married Arthur Marshall, a solicitor, in 1904.[1] She was involved as an active member of the Women's Social and Political Union which had been started by Emmeline Pankhurst in 1903.

.jpg.webp)

The Marshalls had set up the Pankhurst Testimonial Fund to buy Mrs Pankhurst's Devon home, although she did not stay in it much before going to the USA.[1]

Kitty was one of those who carried Mrs Pankhurst coffin at her funeral. Marshall organised the unveiling of the WSPU leader's statue in Westminster in 1930 [2] and was presented with a miniature of the statue to commemorate her involvement.[3]

She died in Halstead, Essex in 1947.

Her husband died in 1954. He had supported and defended WSPU members, and William Ball force-fed and treated inhumanely by the authorities, subject of a pamphlet 'Torture in an English Prison' although these cases affected his business.[1]

Suffragette activism

Marshall delivered the weekly Votes for Women to 10 Downing Street (Number 10), home of the British Prime Minister. Following a campaign of stone-throwing in 1910, Emmeline Pankhurst, Mable Tuke and Kitty Marshall were accused of throwing a stone through a window of number 10, but it may have been a potato thrown at the door.[1]

A celebration lunch reception at the Criterion, Piccadilly for 15 released prisoners and 300 activists who welcomed them was held on 23 December 1910.[1] They heard Mrs Pankhurst speak about the women 'prepared to face all kinds of suffering in order to win for themselves and their daughters that freedom".[1] Marshall then delivered a Christmas hamper and WSPU memorabilia and Christmas card for each remaining Holloway suffragette prisoner.[1]

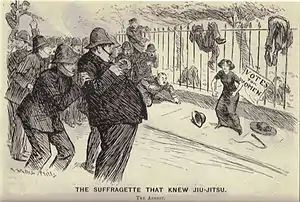

Marshall was one of the WSPU Bodyguards unit and was trained in ju-jitsu by Edith Garrud. She was given a necklace of medals for her service.[4] Marshall wrote about the experiences of using this form of self-defence and other incidents, including acting as wardrobe mistress for disguises and using decoys especially for leaders avoiding re-capture under the "Cat and Mouse Act" in her unpublished memoir titled "Suffragette Escapes and Adventures".[5] Journalists at the time called them the "jiujitsuffragettes" - a portmanteau of "jiujitsu" and "suffragette" - and referred to their tactics as "suffrajitsu".[6]

On 6 February 1911 Marshall was with Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, both well dressed and let through by police as Prime Minister Asquith left Number 10, and they held up a "Give Women the Vote" banner. The Princess's protest was reported in the press but frustratingly did not lead to the publicity associated with a trial and imprisonment.[1] Marshall returned a third time with Marion Wallace-Dunlop to stencil "Votes for Women" on the Prime Minister's doorstep.[1] And at Number 10 suffragette rally, she had once shouted "Charge" and got ten days in prison.[1]

_Damage_done_by_London_Suffragettes_LCCN2014690204.jpg.webp)

Marshall was with Emmeline Pankhurst and Mabel Tuke on 1 March 1912, and all were arrested after pulling up in a taxicab and stoning two windows of Number 10 (as Mrs Pankurst's stone missed). Within an hour, the campaign of 150 suffragettes (a few every quarter of an hour) broke the windows in shops and in commercial property across Haymarket, Piccadilly, Regent Street, the Strand, Oxford Street and Bond Street.[1] Within one day 125 were arrested for causing £5,000 of wilful damage.[1][3]

At their trial for conspiracy, Mrs Pankhurst and Marshall were sentenced to two months (her third prison term), Mabel Tuke sentenced to three weeks.[1] Marshall wrote about the chaos at Holloway with over a hundred women on remand trying to be separated from those convicted. All were singing The Marseillaise to suffragette lyrics, and breaking the glass windows of cells for air. Marshall said "I believe the row we made could be heard some miles away." Marshall was given five days in a 'bitterly cold' underground solitary confinement cell for breaking 40 panes in the prison. This led to a depression, constant crying, transfer to the hospital wing, and her release on 12 April.[1]

In 1913, Marshall and her husband sheltered Grace Roe.[1] Roe had been disguised by the Marshalls in Kitty's clothes which she describes as 'racy' so she could travel to and from Paris, to see Christabel Pankhurst.[7] She was the WSPU head of operations after she took over from Annie Kenney who had been imprisoned.[8] Roe was then evading her own arrest for conspiracy, and ill from her journey after visiting Christabel Pankhurst in Paris for instructions for the movement. Marshall lent her 'racy' clothes as disguise, a heavy veil and toque hat.[1]

References

- Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 238, 247–8, 272, 292, 406, 549. ISBN 9781408844045. OCLC 1016848621.

- Pugh, Martin. (2001). The Pankhursts. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9781448162680. OCLC 615842857.

- Crawford, Elizabeth (2001). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866-1928. Psychology Press. pp. 385, 690+. ISBN 9780415239264.

- "Votes for Women exhibition". Museum of London. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- Marshall, Emily Katherine Willoughby. Suffragette Escapes and Adventures (typescript memoir). Museum of London Suffragette Collections. 61.218/2.

- "Suffrajitsu – The Jiu Jitsu Teacher of the Woman's War". Women's History Network. 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "Women's Hour - Grace Roe". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "Woman's Hour - Grace Roe". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-07-31.