Khurshid Anwar (Major)

Khurshid Anwar was an activist of All-India Muslim League, heading its private militia, the Muslim League National Guard. Described as a "shadowy figure" and "complete adventurer", he is generally addressed as a "Major" in Pakistani sources. He was a key figure in the rise of the Muslim League during 1946–47, organising its campaigns in Punjab and North-West Frontier Province, prior to India's partition. After the independence of Pakistan, he was instrumental in organising the tribal invasion of Kashmir, leading to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947.

Early career

Khurshid Anwar is said to be a native of Jullundhar in Punjab.[1][2] Some sources also state that he was a Pathan from the North-West Frontier Province.[3] His wife, Begum Mumtaz Jamal is said to be a Kashmiri Pathan.[1] Anwar has been described as a "shadowy figure", "complete adventurer",[3][4] and a "Muslim League's most important secret weapon in the creation of Pakistan".[5]

Anwar is said to have worked as an official in the civil supplies department in Delhi prior to World War II. Due to the close association of this department with the military during the War, he is said to have been given the rank of a Major. He is generally referred to as a "Major" in Pakistani sources. Anwar was suspected of bribe-taking and supplying goods to civilians. This ended his association with the Army.[2][3]

Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League had a volunteer militia called the Muslim League National Guard, originally headed by Sardar Shaukat Hayat Khan, a retired Major of the Indian Army. When Hayat Khan stepped down to due to lack of time, Khurshid Anwar was appointed as its commander (Salar) in October 1946. He was given a target of rising 200,000 volunteers. Anwar is said to have devoted 'considerable energy' to the effort, impressing upon the League workers the danger posed by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which was, in his view, financed by the Indian National Congress.[6] By the end of 1946, the National Guard ranks swelled to 60,000 members. The 1946 Bihar riots were instrumental in mobilising the Muslims of India to activism.[3]

When the Muslim League led a civil disobedience movement against the Unionist government of Punjab, vexing its prime minister Khizar Hayat Tiwana, Tiwana banned the Muslim League National Guard in January 1947. But Anwar went underground to keep the agitation going. Eventually the Unionist government was overthrown.[7]

Afterwards, Anwar went to the North-West Frontier Province, where he worked with the Muslim League leaders Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan and Pir of Manki Sharif to launch a direct action campaign against the Congress government.[7] He is said to have organised an underground movement publishing cyclostyled newspapers and broadcasting on a wireless transmitter.[8] Anwar's rallies led to attacks on the local communities of Hindus and Sikhs,[9] generating a stream of refugees into Kashmir, which closed off any possibility of the Maharaja of Kashmir acceding to Pakistan.[10] Anwar is also said to have gotten away with a good deal of loot from his attacks on the minorities.[8]

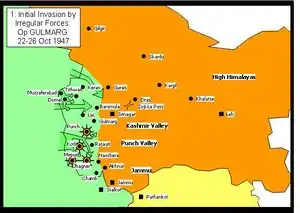

Invasion of Kashmir

On 12 September 1947, the Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan held a meeting in Lahore to formulate a strategy for capturing Kashmir. The meeting was attended by Punjab politicians Mian Iftikharuddin and Sardar Shaukat Hayat Khan, Colonel Akbar Khan, Major General Zaman Kiani and Khurshid Anwar. A three-pronged approach was decided at the meeting, for Akbar Khan to organise the rebellion inside Kashmir, General Kiani to organise an invasion from the south using former Indian National Army personnel, and for Anwar to organise an invasion via Muzaffarabad using activists from Pakistan.[11][12][13][14]

No decision was apparently made in the 12 September meeting to involve Pashtun tribes. Shaukat Hayat Khan writes that he had explicitly ordered Anwar not to involve them. According to him, Anwar had 'disobeyed' by recruiting the Mahsud tribesmen of Waziristan and also by contacting the Pakistan Army. His allies in the effort were Abdul Qayyum Khan, the premier of the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), the Pir of Wana and the Pir of Manki Sharif. Both the Pirs wanted to launch a jihad against Kashmir to free their Muslim brethren from Hindu rule.[15]

According to Shaukat Hayat Khan, they had fixed a 'D-day' in September, but discovered that Anwar had married a Muslim League worker in Peshawar and disappeared on a honeymoon.[16] Anwar himself has given other 'D-days': 15 October in one instance,[17] and 21 October in another.[18] Eventually, the invasion did take place on 22 October.

With the help of the NWFP Chief Minister Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan, the divisional commissioner Khawaja Abdur Rahim of Rawalpindi and the political agents of the tribal agencies, Anwar mobilised Afridis from the Khyber Agency and Mehsuds from the Waziristan Agency.[19][1] They were further joined by Wazirs, Daurs, Bhittanis, Khattaks, Turis, Swatis and men of Dir.[20] Trucks belonging to the paramilitary Frontier Corps were used to transport them to the Kashmir border.[20]

On 22 October 1947, Anwar entered Kashmir near Muzaffarabad heading a lashkar of 4,000 tribesmen.[21] They quickly secured Muzaffarabad, took Uri and proceeded to Baramulla. At each location, they stopped to plunder the local population, especially the Hindus and Sikhs. It was part of their agreement with Anwar; "they had no other remuneration," according to Colonel Akbar Khan.[22] When they reached, Baramulla, a rich provincial capital, their desire for loot was overwhelming and they stopped listening to Anwar's orders. Anwar and some of the tribal elders grew deeply ashamed of what was done in Baramulla.[23]

The tribal lashkar stopped in Baramulla for two days, during which the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir negotiated his accession to India and India dispatched troops by air. According to some accounts, Anwar asked for an undertaking from the tribal leaders to abstain from looting, respect Government property and protect treasuries. The tribesmen are said to have refused. Scholar Andrew Whitehead states that Anwar appears to have summoned political and religious leaders of the tribesmen to instil discipline in them. The Pir of Manki Sharif himself was among them.[24]

On 29 October, Governor George Cunningham of NWFP claims to have convinced Mohammad Ali Jinnah of providing better support to the tribal lashkar. Consequently, the government decided to maintain a contingent of 5,000 tribesmen in Kashmir, provide their rations and ammunition, and establish a directing committee of five officials in Abbottabad to control recruiting and supplies. A battalion of troops was also sent to maintain order among tribesmen.[25]

After the tribesmen advanced again, about 1,000 of them reached Budgam by 3 November, which was within five miles of the Srinagar airfield. Here they were engaged by Indian troops. According Brigadier L. P. Sen of the Indian Army, they failed to press home their advantage in reaching the airfield. Anwar stated that he reached within one mile of the airfield along with twenty men, but lacked the strength to press forward.[26] Around 6 November, Srinagar was exposed to its closest encounter with the war as the city "reverberated to the sound of machine-gun and mortar firing". Three hundred tribesmen faced a roadblock of the Indian Army 4.5 km west of the city, and engaged in a pitched battles in the early hours of the morning. By dawn, they were repulsed.[27] The tribesmen then gathered at Shalateng, northwest of Srinagar. The Indians deployed newly arrived armoured cars and air support. The tribesmen were routed, with heavy casualties, and dispersed. The Indians pursued them and recaptured Pattan, Baramulla and Uri within the next few days.[28]

Around 10 November, Anwar was injured in leg by a bomb splinter and was evacuated to Abbottabad. Colonel Akbar Khan took over the command of the tribal lashkar.[29]

References

- Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2 2015, p. 174.

- Hiro, The Longest August 2015, pp. 117-118.

- Hajari, Midnight's Furies 2015, p. 63.

- Panigrahi, India's Partition 2004, p. 65, 307.

- Jha, The Origins of a Dispute 2003, p. 31.

- Jalal, Self and Sovereignty 2002, p. 482.

- Hiro, The Longest August 2015, Chapter 6.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, p. 55.

- Hajari, Midnight's Furies 2015, Chapter 4.

- Jha, The Origins of a Dispute 2003, p. 170.

- Jha, The Origins of a Dispute 2003, p. 30.

- Lamb, Incomplete Partition 2002, p. 125.

- Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited 2008, pp. 120-121.

- Jamal, Shadow War 2009, pp. 48-49.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, p. 53–55.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, p. 52.

- Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2 2015, p. 174: "In early October Khurshid Anwar came to Pindi and asked Syed Nazir Hussain Shah for four or five guides on the 12th of October to guide his five hundred men to the airfield in Srinagar. He claims that the original plan was to attack Muzaffarabad on the 15th of October."

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, p. 60: "Khurshid Anwar, the man who can best be described as the military commander of the invasion of the Kashmir Valley, said that D-day had been fixed for Tuesday, 21 October, but had to be delayed until the following morning."

- Jamal, Shadow War 2009, p. 50.

- Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 50.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, p. 60.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, p. 61.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, pp. 124–125.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, pp. 133–134.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, pp. 136–137.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, pp. 156.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, pp. 157–158.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, pp. 159–160.

- Whitehead, A Mission in Kashmir 2007, p. 191.

Bibliography

- Amin, Maj Agha Humayun (1999), "The 1947-48 Kashmir War: The war of lost opportunities", The Pakistan Army Till 1965, Strategicus and Tactitus

- Hajari, Nisid (2015), Midnight's Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India's Partition, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0-547-66924-3

- Hiro, Dilip (2015), The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan, Nation Books, ISBN 978-1-56858-503-1

- Jalal, Ayesha (2002), Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0

- Jamal, Arif (2009), Shadow War: The Untold Story of Jihad in Kashmir, Melville House, ISBN 978-1-933633-59-6

- Jha, Prem Shankar (2003), The Origins of a Dispute: Kashmir 1947, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-566486-7

- Lamb, Alastair (2002) [first published 1997 by Roxford Books], Incomplete Partition: The Genesis of the Kashmir Dispute, 1947-1948, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Schofield, Victoria (1997), "Kashmir – Today, Tomorrow?", Asian Affairs, 28 (3): 315–324, doi:10.1080/714857150

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

- Nawaz, Shuja (May 2008), "The First Kashmir War Revisited", India Review, 7 (2): 115–154, doi:10.1080/14736480802055455

- Panigrahi, Devendra (2004), India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-76813-3

- Saraf, Muhammad Yusuf (2015) [first published 1979 by Ferozsons], Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2, Mirpur: National Institute Kashmir Studies

- Whitehead, Andrew (2007), A Mission in Kashmir, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-670-08127-1