King of Easter Island

Easter Island was traditionally ruled by a monarchy, with a king as its leader.

First paramount chief

The legendary first paramount chief of Easter Island is said to have been Hotu Matuꞌa, who supposedly arrived around 800 to 900 AD.[1] Legend insists that this man was the chief of a tribe that lived on Marae Renga. The Marae Renga is said to have existed in a place known as the "Hiva region". Some books suggest that the Hiva region was an area in the Marquesas Islands, but today it is believed that the ancestral land of the Easter Islanders would have been located in the Pitcairn Mangareva intercultural zone. Some versions of the story claim that internal conflicts drove Hotu Matuꞌa to sail with his tribe for new land, while others say a natural disaster, possibly a tidal wave, caused the tribe to flee.

Despite these differences, the stories do agree on the next part: A priest named Haumaka appeared to Hotu Matuꞌa in his dreams one night. The priest flew out to sea and discovered an island which he called Te Pito ꞌo te Kāinga, which means "the center of the earth". Sending seven scouts, Hotu Matuꞌa embraced his dream and awaited the return of his scouts. After eating, planting yams, and resting, the seven scouts returned home to tell of the good news. Hotu Matuꞌa took a large crew along with his family and everything they needed to survive in the new land. They then rowed a single huge double-hulled canoe to "the center of the earth"[2] and landed at Anakena, Rapa Nui.

Tuꞌu ko Iho

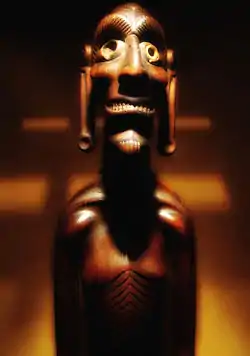

According to Steven Roger Fischer's Island at the End of the World, a certain individual named Tuꞌu ko Iho co-founded the settlement on the island. He not only did this, but as Fischer's book claims, a legend says he "brought the statues to the island and caused them to walk."[3]

Children of Hotu Matuꞌa

Shortly before the death of Hotu Matuꞌa, the island was given to his children, who formed eight main clans. In addition, four smaller and less important clans were formed.

- Tuꞌu Maheke: the firstborn son of Hotu. He received the lands between Anakena and Maunga Tea-Tea.

- Miru: received the lands between Anakena and Hanga Roa.

- Marama: received the lands between Anakena and Rano Raraku. Having access to the Rano Raraku quarry proved extremely useful for those living in Marama's lands. The quarry soon became the island's main source of Tuff used in the construction of the Moai (large stone statues). In fact, 95% of the moai were made in Rano Raraku.[4]

- Raa settled to the northwest of Maunga Tea-Tea.

- Koro Orongo made a settlement between Akahanga and Rano Raraku.

- Hotu Iti was given the whole eastern part of the island.

- and 8. Tupahotu and Ngaure were left with the remaining parts of the island.[5]

Royal patterns throughout Easter Island

Over the years, the clans slowly grouped together into two territories. The Ko Tuꞌu Aro were composed of clans in the northwest, while the Hotu Iti were mainly living in the southeast part of the island. The Miru are very commonly seen as the true royal heirs, who ruled the Ko Tuꞌu Aro clans.

Since then, leaders of Easter Island have been hereditary rulers who claimed divine origin and separated themselves from the rest of the islanders with taboos. These ariki not only controlled religious functions in the clan, but also ran everything else, from managing food supplies to waging war.[6] Ever since Easter Island was divided into two super-clans, the rulers of Easter Island followed a predictable pattern. The people of Rapa Nui were especially competitive during those times. They usually competed to build a bigger moai than their neighbors, but when this failed to resolve the conflict the tribes often turned to war and throwing down each other's statues.

Historical period

.jpg.webp)

With the arrival of the Europeans, the traditional social organization underwent many changes. In 1862–63 the island was subject to numerous Peruvian slave raids, and many chiefs and religious leaders were kidnapped and sold as slaves in Peru. Later 15 islanders were returned, but they were infected with smallpox and tuberculosis which spread across the island decimating its population. This was allegedly the fate of the son of Ngaꞌara II, called Kai Makoꞌi ꞌIti, who was Easter Island's ariki mau or paramount chief at the time, and of his son Maurata. In 1872 the total population was of only 111 individuals, and the paramount chiefs and their priests had perished, thus facilitating their conversion to Christianity.

In 1887, when Chile wanted to annex Easter Island, it became necessary to appoint new local authorities to be able to sign the treaty and accept the sovereignty of Chile, so the Bishop of Tahiti decided to appoint a very pious islander as king, a title that did not exist before on Easter Island. This title befell on Tekena, who was baptized as Atamu Tekena or "Adam" Tekena and his wife as "Eve". He was not a traditional chief, and could not trace his descent from the paramount chiefs' lineage, so upon his death, the islanders decided to choose by popular election the new heir between the Hereveri, Ika and Riroroko families, as all of which could trace descent from the last line of paramount chiefs. Simeon Riro Kainga won the election and was appointed king in 1890. The situation of the islanders deteriorated in the following years, becoming slaves on their own land, once the island was rented out to a private party. The new exploiters converted all the island into a sheep and cattle ranch, and enclosed the population by force in a small land in front of the bay of Hangaroa, surrounded by a high stone wall. They were forbidden to leave it, plant or fish, and their cattle and their ancestral lands were stolen. King Simeon Riro Kainga decided then to travel to mainland Chile in the company of two of his ministers, to present their complaints to the government and ask Chile to comply with the agreement signed in the document of annexation in 1888. At the time the only means to travel to mainland Chile was on board the Company ships that visited the island regularly, and upon arriving to Valparaiso the owner of the company who rented the island decided to murder King Riro Kainga to avoid his contact with the Chilean authorities. King Riro Kainga was poisoned upon arrival, and died a day later in a hospital in Valparaiso. From then onwards the islanders were forbidden to appoint an heir as king. During the presidency of Michel Bachelet, the mortal remains of King Riro Kainga were returned to Easter Island (which is known today as Rapa Nui), and a monument was erected to his memory in the plaza in front of the Governor's Office.

In 1956, his grandson Valentino Riroroko Tuki, in the company of three of his brothers and a relative, escaped the island in a small open row boat with an added sail, measuring only 6 meters in length, to obligate the Chilean authorities to grant them the freedom to leave the island at will. This was not the first boat to escape, and in several earlier attempts about 17 islanders lost their lives at sea. King Valentino in his boat after 56 days made it safely to Atiu in the Cook Islands, a nearly 3,000-mile, open-sea voyage. After all the publicity this trip engendered, Chilean authorities were obliged to allow the islanders to travel off the island at will. In 2011, he was appointed king. His title so far does not carry any real power in the actual island government, or the way Chile manages the island today. Nevertheless, he is looked upon with respect by the islanders, and a large number of them are petitioning the government to obtain more autonomy, recognition, and empowerment of their traditional authority, as agreed upon in the treaty celebrated in 1888 when they accepted the sovereignty of Chile and in accordance with the United Nations resolution, to which Chile subscribes, that regulates the rights of indigenous peoples. These petitions are subscribed by a local political movement known as the Parlamento Rapa Nui, and its lawyers. Each year a celebration is carried out to remember and honor his grandfather King Riro, who gave his life for the islanders, and who has now become a cultural hero. In 2012, over 600 islanders attended the lunch offered by the king, and a Chilean folkloric dance group from mainland Chile danced at the event.

Lists of the paramount chiefs and historical kings of Easter Island

- 1 Hotu (A Matua), son of Matua (c. 400)

- 2 Vakai, his wife

- 3 Tuu ma Heke

- 4 Nuku (Inukura?)

- 5 Miru a Tumaheke

- 6 Hata a Miru

- 7 Miru o Hata

- 8 Hiuariru (Hiu a Miru?)

- 9 Aturaugi. The first obsidian spearheads were used.

- 10 Raa

- 11 Atahega a Miru (descendant of Miru?), around 600

- ......Hakapuna?

- 17 Ihu an Aturanga (Oihu?)

- ......Ruhoi?

- 20 Tuu Ka(u)nga te Mamaru

- 21 Takahita

- 22 Ouaraa, around 800

- 23 Koroharua

- 24 Mahuta Ariiki (The first stone images were made in his son's time.)

- 25 Atua Ure Rangi

- 26 Atuamata

- 27 Uremata

- 28 Te Riri Tuu Kura

- 29 Korua Rongo

- 30 Tiki Te Hatu

- 31 Tiki Tena

- 32 Uru Kenu, around 1000

- 33 Te Rurua Tiki Te Hatu

- 34 Nau Ta Mahiki

- 35 Te Rika Tea

- 36 Te Teratera

- 37 Te Ria Kautahito (Hirakau-Tehito?)

- 38 Ko Te Pu I Te Toki

- 39 Kuratahogo

- 40 Ko Te Hiti Rua Nea

- 41 Te Uruaki Kena

- 42 Tu Te Rei Manana, around 1200

- 43 Ko Te Kura Tahonga

- 44 Taoraha Kaihahanga

- 45 Tukuma(kuma)

- 46 Te Kahui Tuhunga

- 47 Te Tuhunga Hanui

- 48 Te Tuhunga Haroa

- 49 Te Tuhunga "Mare Kapeau"

- 50 Toati Rangi Hahe

- 51 Tangaroa Tatarara (Maybe Tangaiia of Mangaia Island ?)

- 52 Havini(vini) Koro (or Hariui Koro), about 1400

- 53 Puna Hako

- 54 Puna Ate Tuu

- 55 Puna Kai Te Vana

- 56 Te Riri Katea (? - 1485)

- 57 -

- 58 -

- 59 HAUMOANA, TARATAKI and TUPA ARIKI (from Peru), from 1485

- 60 Mahaki Tapu Vae Iti (Mahiki Tapuakiti)

- 61 Ngau-ka Te Mahaki or Tuu Koiho (Ko-Tuu-ihu?)

- 62 Anakena

- 63 Hanga Rau

- 64 Marama Ariki, around 1600

- 65 Riu Tupa Hotu (Nui Tupa Hotu?)

- 66 Toko Te Rangi (Perhaps the "God" Rongo of Mangaia Island?)

- 67 Kao Aroaro (Re Kauu?)

- 68 Mataivi

- 69 Kao Hoto

- 70 Te Ravarava (Terava Rara)

- 71 Tehitehuke

- 72 Te Rahai or Terahai

(The alternative rulers after Terahai: Koroharua, Riki-ka-atea, whose son was Hotu Matua, then Kaimakoi, Tehetu-tara-Kura, Huero, Kaimakoi (or Raimokaky), finally Gaara who is Ngaara on the main list below.)

- 73 Te Huke

- 74 Tuu, from Mata Nui (Ko Tuu?), around 1770

- 75 Hotu Iti (born from Mata Iti). War around 1773.

- 76 Honga

- 77 Te Kena

- 78 Te Tite Anga Henua

- 79 Nga'ara (c. 1835 - just before 1860), son of King Kai Mako'i

- 80 Maurata (1859 – 1862)

- 81 Kai Mako'i 'Iti (= Small Kaimakoi) (- 1863), son of Nga'ara, devastation of island by Peruvian slavers in the great Peruvian slaving raid of 1862, died as a slave (in 1863?)

- 82 Tepito[7]

- 83 Gregorio;[7] i. e. Kerekorio Manu Rangi, Rokoroko He Tau

- 84 Atamu Tekena, signs Treaty of Annexation, Easter Island is annexed, died August 1892[8]

- 85 Simeon Riro Kāinga, died in Chile in 1899

- 86 Enrique Ika a Tuʻu Hati (1900–1901), not recognized[9]

- 87 Moisés Tuʻu Hereveri (1901–1902), not recognized.[9]

- Modern claimant

- 2011-current: Valentino Riroroko Tuki (crowned July 2011)[10] claimed to be the actual King and grandson of Kāinga.

References

- Edmundo Edwards When The Universe was an Island Archaeology and Ethnology of Easter Island. Page 18, Ediciones Reales 2012 Carlos Mordo, Easter Island (Willowdale, Ontario: Firefly Books Ltd., 2002) Page 14

- Mordo: P. 49

- Steven Roger Fischer, Island at the End of the World (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2005) P. 38

- Mordo: P. 109

- Mordo: P. 50

- Mordo: P. 50-51

- Englert, Sebastián (2004). La tierra de Hotu Matu'a: historia y etnología de la Isla de Pascua : gramática y diccionario del antiguo idioma de Isla de Pascua. Editorial Universitaria. p. 65. ISBN 978-956-11-1704-4.

- RAPA NUI: INDIGENOUS STRUGGLES FOR THE NAVEL OF THE WORLD

- Pakarati, Cristián Moreno (2015) [2010]. Los últimos 'Ariki Mau y la evolución del poder político en Rapa Nui. pp. 13–15.

Further reading

- Alfred Metraux (1937). "The Kings of Easter Island". Journal of the Polynesian Society. Polynesian Society. 46: 41–62.