Labanotation

Labanotation or Kinetography Laban is a notation system for recording and analyzing human movement that was derived from the work of Rudolf Laban who described it in Schrifttanz (“Written Dance”) in 1928. His initial work has been further developed by Ann Hutchinson Guest and others, and is used as a type of dance notation in other applications including Laban Movement Analysis, robotics and human movement simulation.

Technical standards and education for Labanotation are provided by several organizations. For example, the International Council of Kinetography Laban / Labanotation promotes standards and development for Labanotation. The Dance Notation Bureau has been using Labanotation to document dances since 1940, holding the largest collection of Labanotation scores in the world. It also teaches Labanotation and arranges the staging of dances from the system scores.

History

In 1927, Kurt Jooss and Sigurd Leeder began working on a movement notation system that they presented to Rudolf Laban (then Rudolf von Laban) who took up the task of expanding on it, creating Labanotation. In 1928, Labanotation, which was then known as kinetography, was formally presented at the Second German Dancers' Congress, which was organized by Jooss, in Essen, Germany.[1]

This notation system could be used to describe movement in terms of spatial models and concepts, which contrasts with other movement notation systems based on anatomical analysis, letter codes, stick figures, music notes, track systems, or word notes. The system precisely and accurately portrays temporal patterns, actions, floor plans, body parts and a three-dimensional use of space. Laban's notation system eventually evolved into modern-day Labanotation and Kinetography Laban.

Labanotation and Kinetography Laban evolved separately in the 1930s through 1950s, Labanotation in the United States and England, and Kinetography in Germany and other European countries. As a result of their different evolutionary paths, Kinetography Laban hasn't changed significantly since inception, whereas Labanotation evolved over time to meet new needs. For example, at the behest of members of the Dance Notation Bureau, the Labanotation system was expanded to allow it to convey the motivation or meaning behind movements. Kinetography Laban practitioners, on the other hand, tend to work within the constraints of the existing notation system, using spatial description alone to describe movement.[2]

The International Council of Kinetography Laban was created in 1959 to clarify, standardize and eliminate differences between Labanotation and Kinetography Laban. Thanks to this, one or both are currently used throughout the world almost interchangeably, and are readable to practitioners of either system.

Main concepts

Labanotation uses abstract symbols to define the:

- Direction and level of the movement

- Part of the body doing the movement

- Duration of the movement[3]

- Dynamic quality of the movement

Direction and level of the movement

The shapes of the direction symbols indicate nine different directions in space and the shading of the symbol specifies the level of the movement.

Each "direction symbol" indicates the orientation of a line between the proximal and distal points of a body part or a limb.[4] That is, "the direction signs indicate the direction towards which the limbs must incline". [5]

The direction symbols are organized as three levels: high, middle, and low (or deep):

| Labanotation direction symbols | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Hover mouse over symbols to see their names) | |||||||

| High Level | left-forward-high | forward-high | right-forward-high | ||||

| left-high | place-high | right-high | |||||

| left-back-high | back-high | right-back-high | |||||

| Middle Level | left-forward-middle | forward-middle | right-forward-middle | ||||

| left-middle | place-middle | right-middle | |||||

| left-back-middle | back-middle | right-back-middle | |||||

| Low Level | left-forward-Low | forward-Low | right-forward-Low | ||||

| left-Low | place-Low | right-Low | |||||

| left-back-Low | back-Low | right-back-Low | |||||

Part of the body doing the movement

Labanotation is a record of the facts, the framework of the movement, so that it can be reproduced.

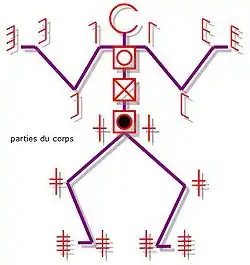

The symbols are placed on a vertical staff, the horizontal dimension of the staff represents the symmetry of the body, and the vertical dimension represents time passing by.

The location of a symbol on the staff defines the body part it represents. The centre line of the staff represents the centre line of the body, symbols on the right represent the right side of the body, symbols on the left, the left side.

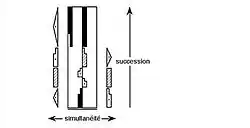

Duration of the movement

The staff is read from bottom to top and the length of a symbol defines the duration of the movement. Drawing on western music notation, Labanotation uses bar lines to mark the measures and double bar lines at the start and end of the movement score. The starting position of the dancer can be given before the double bar lines at the start of the score.

Movement is indicated as "the transition from one point to the next", that is as one "directional destination" to the next.[6]

Spatial distance, spatial relationships, transference of weight, centre of weight, turns, body parts, paths, and floor plans can all be notated by specific symbols. Jumps are indicated by an absence of any symbol in the support column, indicating that no part of the body is touching the floor.

Dynamic quality of the movement

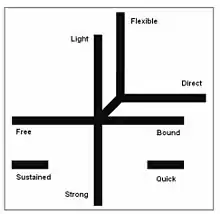

The dynamic quality is often indicated through the use of effort signs (see Laban Movement Analysis).

The four effort categories are[7]

- Space: Direct / Indirect

- Weight: Strong / Light

- Time: Sudden / Sustained

- Flow: Bound / Free

Dynamics in Labanotation are also indicated through a set of symbols indicating a rise or lowering of energy resulting from physical or emotional motive, e.g. physically forceful versus an intense emotional state.

Motif notation

Motif description, or the preferred term 'Motif notation', is closely related to Labanotation in its use of the same family of symbols and terminology. Labanotation is used for a literal, detailed description of movement so it can be reproduced as it was created or performed. In contrast, Motif Notation highlights core elements and leitmotifs depicting the overall structure or essential elements of a movement sequence. It can be used to set a structure for dance improvisation or for an educational exploration of movement concepts. Not limited to dance, Motif Notation can be used to direct one's focus when learning to swing a golf club, the primary features of a character in a play, or the intent of a person's movement in a therapy session.

References

- Guest, Ann Hutchinson. (11 October 2013). The green table : a dance of death in eight scenes. Jooss, Kurt, 1901-1979., Cohen, Frederic A., 1901-1967., Markard, Anna, 1931-. [Place of publication not identified]. ISBN 978-1-136-72456-5. OCLC 919306096.

- Interview with Ann Hutchinson Guest (August, 2012).

- "Handbook for Laban Movement Analysis" Written and Compiled by Janis Pforsich. copyright Janis Pforsich 1977

- Hutchinson, Ann. Labanotation or Kinetography Laban: The System of Analyzing and Recording Movement (1954, 1970, 1977). New York: Theatre Arts Books. pp. 164-170.

- Knust, Albrecht. Dictionary of Kinetography Laban (Labanotation); Volume I (1979). Plymouth: MacDonald and Evans. p. 14

- Hutchinson, Ann. Labanotation or Kinetography Laban: The System of Analyzing and Recording Movement (1954, 1970, 1977). New York: Theatre Arts Books. pp. 15, 29.

- Laban, Rudolf, and Lawrence, F. C. Effort. (1947). London: MacDonald and Evans.

Further reading

- Guest, Ann Hutchinson (2005). Labanotation: the system of analyzing and recording movement (4th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-62612-2.

- Hutchinson-Guest, Ann. (1983). Your Move: A New Approach to the Study of Movement and Dance. New York: Gordon and Breach.

- Hutchinson-Guest, Ann. (1989). Choreo-Graphics; A Comparison of Dance Notation Systems from the Fifteenth Century to the Present. New York: Gordon and Breach.

- Knust, Albrecht. (1948a). The development of the Laban kinetography (part I). Movement. 1 (1): 28–29.

- Knust, Albrecht. (1948b). The development of the Laban kinetography (part II). Movement. 1 (2): 27-28.

- Knust, Albrecht. (1979a). Dictionary of Kinetography Laban (Labanotation); Volume I: Text. Translated by A. Knust, D. Baddeley-Lang, S. Archbutt, and I. Wachtel. Plymouth: MacDonald and Evans.

- Knust, Albrecht. (1979b). Dictionary of Kinetography Laban (Labanotation); Volume II: Examples. Translated by A. Knust, D. Baddeley-Lang, S. Archbutt, and I. Wachtel. Plymouth: MacDonald and Evans.

- Laban, Rudolf (1975). Laban’s Principles of Dance and Movement Notation. 2nd edition edited and annotated by Roderyk Lange. London: MacDonald and Evans. (First published 1956.)

- Laban, Rudoph. (1928). Schrifttanz. Wein: Universal.

- Preston-Dunlop, V. (1969). Practical Kinetography Laban. London: MacDonald and Evans.

- El Raheb, Katerina; Ioannidis, Yannis (2012). "A Labanotation Based Ontology for Representing Dance Movement". Gesture and Sign Language in Human-Computer Interaction and Embodied Communication. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 7206. pp. 106–117. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-34182-3_10. ISBN 978-3-642-34181-6.

- Longstaff, J. S. (September 1996). Cognitive Structures of Kinesthetic Space Reevaluating Rudolf Laban's Choreutics In the Context of Spatial Cognition and Motor Control (doctoral). City University London.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Labanotation. |

- Dance Notation Bureau website

- International Council of Kinetography Laban website

- Laban Lab (learn the basics of Labanotation)