Lampião

"Captain" Virgulino Ferreira da Silva (Brazilian Portuguese: [viʁɡulĩnu feˈʁejɾɐ da ˈsiwvɐ]), better known as Lampião (older spelling: Lampeão, Portuguese pronunciation: [lɐ̃piˈɐ̃w], meaning "lantern" or "oil lamp"), was probably the twentieth century's most successful traditional bandit leader.[1] The banditry endemic to the Brazilian Northeast was called Cangaço. Cangaço had origins in the late 19th century but was particularly prevalent in the 1920s and 1930s. Lampião led a band of up to 100 cangaceiros, who occasionally took over small towns and who fought a number of successful actions against paramilitary police when heavily outnumbered. Lampião's exploits and reputation turned him into a folk hero, the Brazilian equivalent of Jesse James or Pancho Villa.[2]

Lampião | |

|---|---|

_01.jpg.webp) Lampião, photographed in 1926 | |

| Born | Virgulino Ferreira da Silva June 7, 1897 Serra Talhada, Pernambuco, Brazil |

| Died | July 28, 1938 (aged 41) Angicos, Sergipe, Brazil |

| Cause of death | Shot by paramilitary police |

| Occupation | Cangaceiro |

| Known for | Banditry, murder, robbery, extortion |

| Spouse(s) | Maria Déia (Maria Bonita) |

| Children | Expedita Ferreira |

| Parent(s) | José Ferreira da Silva, Maria Lopes |

Biography

Early life

Virgulino was born on June 7, 1897, near the village of Serra Talhada, on his father's 'ranch' named Passagem das Pedras in the semi-arid backlands (sertão) of the state of Pernambuco.[3] He was the third of nine children of José Ferreira da Silva and Maria Lopes, a humble family of subsistence farmers. Until he was 21 years old, he worked hard herding his father's few cattle, sheep and goats, becoming a skilled rider and 'cowboy'. He was also an accomplished leathercraft artisan. Though he never attended school he was literate and used reading glasses—both quite unusual features for the rough and poor region where he lived.[4]

The backlands had little in the way of law and order, even the few police in existence were usually in the pocket of a local "Coronel" – a leading landowner who was also a regional political chief – and would usually take sides in any dispute.[5] Indeed, the poorer portion of the backlands population were generally badly treated by the paramilitary police, and would often prefer the presence of bandits in their settlements over that of the police.[6] In such a society disputes between neighbours could quickly escalate into violent feuding. Virgulino's family fell into a deadly feud with other local families. His father twice moved his family to avoid the escalating dispute, first to Nazaré, and then to Água Branca in the State of Alagoas. These moves proved to be fruitless as violence followed the family, with Virgulino and his brothers Antônio and Levino gaining reputations as troublemakers. Eventually José Ferreira was killed in a confrontation with the police on May 18, 1921. Virgulino sought vengeance and proved to be extremely violent in doing so. He became an outlaw, a cangaceiro, and was incessantly pursued by the police (whom he called macacos or monkeys). Virgulino had acquired the nickname 'Lampião' as early as 1921, allegedly because he could fire a lever-action rifle so fast, that at night it looked as though he was holding a lamp.[7]

Bandit leader

Lampião became associated with an established bandit leader, Sebastião Pereira. After only a few months of operating together, in 1922, Pereira decided to retire from banditry; he moved to the State of Goiás and lived there peacefully into advanced old age. Lampião then took over leadership of the remnants of Pereira's band.[8] For the next 16 years, he led his band of cangaceiros, which varied greatly in number from around a dozen to up to a hundred, in a career of large-scale banditry through seven states of the Brazilian Northeast.[9]

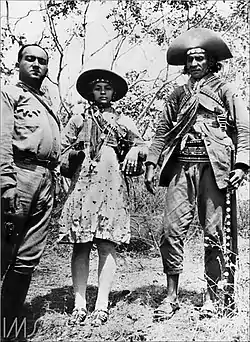

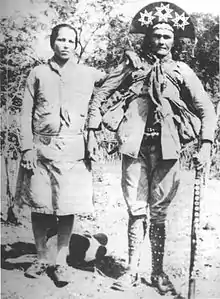

Depending on the terrain and other conditions, the bandits operated either on horseback or on foot. They were heavily armed, and wore leather outfits, including hats, jackets, sandals, ammunition belts, and trousers, to protect them from the thorns of the caatinga, the dry shrub and brushwood typical of the dry hinterland of Brazil's Northeast. The police and soldiers stationed in the backlands often dressed in an identical manner; on more than one occasion Lampião impersonated a police officer, especially when moving into a new area of operations, in order to gain information.[10]

The firearms and ammunition of the cangaceiros were mostly stolen, or acquired by bribery, from the police and paramilitary units and consisted of Mauser military rifles and a variety of small arms including Winchester rifles, revolvers and the prized Luger and Mauser semi-automatic pistols.[11]

A strange and contradictory piety ran through Lampião's psyche: while robbing and killing people, he also prayed regularly and reverenced the Church and priests. He wore many religious symbols on his person; presumably, he invested them with talismanic qualities.[12] Like many others in the region he particularly revered Padre Cícero, the charismatic priest of Juazeiro.[13] He was noted for his loyalty to those he befriended or to whom he owed a debt of gratitude. He generously rewarded his followers and those of the population who shielded or materially helped him (coiteiros), and he was entirely reliable if he gave his word of honour. Lampião was capable of acts of mercy and even charity, however, he systematically used terror to achieve his own survival. His enmity, once aroused, was implacable and he killed many people merely because they had an association with someone who had displeased him. He is recorded as having said "If you have to kill, kill quickly. But for me killing a thousand is just like killing one". For the cangaceiros murder was not only casual, they took pride in their efficiency in killing. They were excellent shots and were skilled in the use of long, narrow knives (nicknamed peixeiras – "fish-filleters") which could be used to dispatch a man quickly.[14]

Lampião's band attacked small towns and farms in seven states, took hostages for ransom, extorted money by threats of violence, tortured, fire-branded, and maimed; it has been claimed that they killed over 1,000 people and 5,000 head of cattle and raped over 200 women. The band fought the police over 200 times and Lampião was wounded six times.[15][16]

A typical example of Lampião's activities, and his ambivalent nature, is his descent on the small town of Queimadas in Bahia, which took place in December 1929. His band entered the town, and immediately shut down the telegraph office to stop news from spreading. The seven policemen in the town and their sergeant were shut in the jail, whilst the jail's previous occupants were set free. The wealthiest citizens of the town were then levied for a forced monetary contribution. The bandits, however, paid for items, including soap and perfume, taken from the town's shops. The seven policemen were summarily executed by shots to the head, but their sergeant was left unharmed as he was liked by the townspeople. In the evening Lampião organised a baile, a dance for the townspeople and his cangaceiros. He also ordered a cinema show to be presented. The bandits were under strict instructions not to molest the local young women, and such was Lampião's authority that none were. The bandits left the town at 4:00 in the morning; Lampião rode a borrowed mule, which he later duly returned to its owner.[17] On one occasion he attacked a large town, Mossoró in the state of Rio Grande do Norte, in June 1927. The bandits began their assault on the town to the sound of a bugle; when advancing they shouted vivas and sang their special song, Mulher Rendeira (The Lacemaker). However, the inhabitants had time to organise a defence, and 300 armed townsmen drove off Lampião's 60 cangaceiros.[18]

As well as engaging in criminal activities for gain or revenge Lampião's band also fought a number of pitched battles with the volantes – mobile units of paramilitary police. Probably the largest of these battles was fought on 28 November 1926 near Serra Grande, twenty miles from Vila Bela. Lampião with around 100 cangaceiros fought off 295 soldiers, killing 10 and wounding a dozen more.[19] At around this time Lampião took to calling himself the "governor of the backlands", only partly in jest.[20]

Lampião was joined in 1930 by his girlfriend, Maria Déia, nicknamed Maria Bonita ("Pretty Maria").[21] His relationship with Maria Bonita gave his reputation some of the 'romance and violence' notoriety enjoyed in the United States by Bonnie and Clyde.[22] The women who joined bandit groups, often termed cangaceiras, dressed like their male comrades and participated in many of their actions. Maria and Lampião had a daughter, named Expedita, in 1932. A number of cangaceiras joined the band over the many years of its existence and Lampião usually attended any births these women had personally. Such children, including Lampião's own, were fostered out to settled relatives or friends of the cangaceiros, or left with priests.[23] Expedita, after the deaths of her parents, was raised by her uncle, João. João Ferreira was the only one of Lampião's brothers not to become an outlaw.[24]

In 1935 Lampião and his band were filmed by Benjamin Abrahão. Once reassured that the camera did not conceal a gun, Lampião co-operated enthusiastically with the filming. The film-stock was soon confiscated by the police, and Abrahão died in 1938. This cinematographic record was rediscovered in 1957, but had physically deteriorated to a great extent. However, several scenes survived, a unique example of moving images of Lampião, Maria Bonita and many other cangaceiros.[25]

Death

On July 28, 1938, Lampião and his band were betrayed by one of his supporters, Joca Bernardes, and were ambushed in one of his hideouts, the Angicos farm, in the state of Sergipe. A police troop, led by João Bezerra and armed with machine guns, attacked the encamped bandits at daybreak. In a brief battle, Lampião, Maria Bonita and nine of his troops were killed, some forty other members of the bandit group managed to escape. The heads of those killed were cut off and sent to Salvador, the capital of Bahia, for examination by specialists at the State Forensic Institute.[26] Later they were put on public exhibition in the city of Piranhas. In 1969, after more than 30 years, the mummified severed heads were removed from display at the Salvador museum and buried in the Quintas Cemetery in Salvador.[27][28]

The end of Cangaço

In the early 1920s a large number of Cangaço bandit groups were in existence. When Lampião became a cangaceiro, joining the Cangaço was almost the equivalent of a career choice. At the time of Lampião's death, he was the only independent bandit leader remaining. However, his major subordinates, such as Luis Pedro, Ângelo Roque and Corisco, often led bandits in semi-independent operations at a considerable distance from the main camp, sometimes across state borders. It was Lampião's intelligence and charisma that ensured that large-scale banditry remained viable in the changing environment of late 1930s Brazil. Within two years of his death Cangaço was a thing of the past. A number of potential bandit leaders, such as Corisco, and lesser bandits were killed; many more gave themselves up to the authorities on assurance of escaping the death penalty. Ângelo Roque gave himself up, along with eight companions, in April 1940 at Bebedouro. Some bandits even turned on colleagues, killing and decapitating them; they then reported to the police with the severed head to show that their renunciation of banditry was sincere.[29]

Notable band members

Lampião was active for a number of years and thus many men and women passed through his band. More notable ones included:

- Antônio Ferreira – Lampião's eldest brother, died in an accident in 1926.

- Levino Ferreira – Lampião's brother, killed in battle with police in July 1925.

- Ezequiel Ferreira – Lampião's youngest brother, killed in battle with police in April 1931.

- Luis Pedro – a lieutenant and member of the band for over a decade, he returned to die by Lampião's side even though he may have been able to escape. He accidentally killed Antônio Ferreira in 1926 when a gun went off during a wrestling bout. When told of his brother's death Lampião said that Luis must take his place.

- Corisco (Cristino Gomes da Silva Cleto) – feared for his cruelty. There was speculation that he would take control of the band after Angicos, where he had not been present. Seeking vengeance for Angicos, Corisco interrogated Joca Bernardes the informant who had betrayed Lampião, who shifted the blame on someone else, Domingos Ventura. Corisco then murdered this entirely innocent person and his whole family, including two women. He was killed by police in 1940.[30]

- Dadá (Sérgia Ribeiro da Silva), the wife of Corisco. She lost a leg as a result of injuries sustained in the fight in which Corisco was killed; she died in 1994.

- Ângelo Roque – a trusted lieutenant who was also not present when Lampião was killed. He operated until 1940 when he surrendered to police after being assured that he would not be executed for his crimes. He was initially sentenced to 95 years in prison, which was later reduced to 30 years and then commuted in 1950.

- Volta Seca ("Dry Gulch" Antônio dos Santos) – joined the bandits aged 14 as a message-carrier. He was later interviewed in prison and his accounts were an important source for the history of Lampião's activities. He composed and sang a number of songs about, or associated with, Lampião's bandits; many years later, in 1957, these were recorded for a sound documentary by Todamérica.

Folk hero

Despite his history of brutal acts and savagery, there was enough in his undoubted courage, his many fights against heavy odds, his occasional acts of mercy and charity, his conventional piety and calculated courting of publicity to ensure that Lampião entered Brazilian folk-history as a hero.[31] One of the more dispassionate analyses of Lampião concluded that, if he was a hero, he was an anarchist hero who forged a prominent place for himself in a society and political environment where people put their own interests above all other considerations.[32]

In 1957 the songs associated with Lampião's bandits were recorded, as "Cantigas de Lampião".

Joan Baez recorded a version of "Mulher Rendeira", renamed "O Cangaceiro", on her album Joan Baez/5 – released in October 1964. The lyrics refer directly to Lampião.

The story of Lampião and Maria Bonita became the subject of innumerable folk stories, books, comics books, popular pamphlets (cordel literature), songs, movies, and a number of TV soap operas, with all the elements of drama, passion, and violence typical of "Wild West" stories.[33]

Capoeira culture honors his folk hero status in a verse of the quadra (call and response style song), 'Sim, Sim, Sim, Não, Não, Não'.[34] Lampião was mentioned in the lyrics of "Ratamahatta", a song of Brazilian metal band Sepultura, from their Roots record. In classical music, the composer Caio Facó wrote a piece (Cangaceiros e Fanaticos, for string quartet) inspired by the theme of Cangaço.[35]

The ultras group of Sport Club do Recife, called Torcida Jovem do Sport, use the myth of Lampião and Maria Bonita as their 'leaders' and symbols.

References

- Chandler, preface, p. xi

- Chandler, p. 3

- Chandler, p. 21

- Chandler, pp. 22–23

- Singelmann, pp. 67–68. A coronel was a political chief who fabricated votes in elections, made Deputies and Senators, had judges appointed and transferred police commanders.

- Singelmann, p. 75

- Chandler, pp. 25–33

- Chandler, p. 5

- Chandler, pp. 58–59

- Chandler, p. 5

- Chandler, pp. 71, 183

- Chandler, pp. 207–208

- Singelmann, p. 79

- Chandler, pp. 200–204

- Chandler, p. 4

- Singelmann, p. 61

- Chandler, pp. 125–128

- Chandler, pp. 95–99

- Chandler, pp. 82–83

- Chandler, p. 85

- Chandler, p. 149

- Eakin, p. 74

- Chandler, pp. 151–152

- Chandler, p. 152

- Chandler, pp. 201–202

- Chandler, pp. 220–230

- "Bandits' Heads Finally Buried", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 10, 1969, p6

- Chandler, p. 239

- Chandler, pp. 231–234

- Chandler, pp. 230–231

- Chandler, pp. 3–5

- Singelmann, pp. 81–82

- Curran, p. 105

- "Every song has an agenda..." October 23, 2008.

- "Encomendas Osesp 2018". osesp.art.br. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

Bibliography

- Chandler, Billy Jaynes (1978). The Bandit King: Lampião of Brazil. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-194-8.

- Curran, M.J. (2010) Brazil's Folk-Popular Poetry - a Literatura de Cordel, Trafford Publishing.

- Eakin, M.C. (1998) Brazil: The Once and Future Country, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Singelmann, Peter (1975) Political Structure and Social Banditry in Northeast Brazil. Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1.

External links

Mulher Rendeira – The song of Lampião's bandits

The special song of Lampião's band—Mulher Rendeira on YouTube—is thought by some to have been composed by Lampião, who is known to have played the accordion, but it seems more likely that it was a traditional tune to which the bandits added their own words.

Olê, Mulher Rendeira, Olê mulher rendá --- "Olê", Lacemaker woman, "Olê" lace woman

A pequena vai no bolso, a maior vai no embornal --- The small [gun] goes in the pocket, the large [gun] in a bag

Se chora por mim não fica, só se eu não puder levar --- Only cry for me, if I cannot take you away

O fuzil de Lampião, tem cinco laços de fita --- The rifle of Lampião, has five ribbons of cloth

O lugar que ele habita, não falta moça bonita --- The place he lives in, does not lack pretty girls